I PRESENT ARMS: DISPLAYING WEAPONS in MUSEUMS a Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Safety Policy and Procedures

Sons of the American Revolution Color Guard Safety Policy and Procedures Purpose The purpose of this document is to establish standardized Safety Policy and Procedures for the National Society, Sons of the American Revolution to be adopted by the National, State and Chapter Color Guards to promote uniformity for multi-state events and to facilitate the acquisition of liability insurance coverage for the Color Guard. State Societies may in their discretion adopt more stringent standards if desirable or required by the laws of their state. Policies A. Insurance: 1. All chapter and/or state societies that have compatriots firing weapons shall have a liability insurance policy that covers events at which Black Powder is fired. 2. All liability insurance policies obtained by a Chapter or State shall name the respective State Society and National Society as additional insureds. B. Training: 1. Before carrying a weapon at an SAR event, all compatriots will be trained in the safe handling of that weapon even if they are not firing. 2. Any compatriot who will be firing shall be additionally trained in the safe operation and firing of their firearm. 3. The recognized standards for training shall be (1) the National Park Service Manual of Instruction for the Safe Use of Reproduction Flintlock Rifles & Muskets in Interpretive Demonstrations (1/21/2010), (2) the NRA NMLRA Basic Muzzle Loading Shooting Course or (3) an equivalent training course taught by an instructor who has been certified by the appropriate State Color Guard Commander. If the color guardsman receives training from an outside source such as the NRA or NPS, the State Color Guard Commander or his designee will examine the color guardsman for familiarity with SAR uses of a firelock and provide additional training as necessary. -

Two Guncases Panoply of Viennese Flintlock Firearms

ing from the early eighteenth century (inv. nos. 38p-J3), and 100 Anton Klein (act. 1753-82) by a pair of fowling pieces dating from about 1760 (inv. nos. 206-7). Johann Lobinger (act. TWO GUNCASES 1745-88), court gunmaker to Prince Joseph Wenzel, made an Austrian (Vienna), mid-z8th century other pair of guns dating about 1770 mounted with Italian bar Wood, velvet, iron, gold; length 5831,. in. (z4g.2 em.); width zo in. (25.3 em.); height g?/s in. (25 em.) rels by Beretta (inv. nos. 426, 430). The firearms in this panoply are generally similar in appear The boxes are constructed of wood and are covered with red velvet with gold ance, with blued barrels, walnut stocks, and gilt-brass mounts, borders and bands. The hinges, locks, and carrying handles are gilded iron. including escutcheons engraved with the Liechtenstein coat of The interior of each is fitted with compartments for three guns (which traveled arms. The guns by Klein and Lobinger have wooden trigger upside down), lined with green velvet with gold .bands and equipped with a guards, a feature frequently found on Central European flintlocks stuffed and tufted cushion of green velvet with gold tassels to cover the guns. of the eighteenth century. SWP SWP 100 102 PANOPLY OF WHEELLOCK FIREARMS This panoply, composed of fifty-two wheellock rifles and pistols, represents a cross-section of the great collection of wheellock arms in the Liechtenstein Gewehrkammer. The majority are hunt ing rifles made by gunmakers in Austria, Bohemia, Moravia, and Silesia, where the Liechtensteins had their estates. -

Federal Court Between

Court File No. T-735-20 FEDERAL COURT BETWEEN: CHRISTINE GENEROUX JOHN PEROCCHIO, and VINCENT R. R. PEROCCHIO Applicants and ATTORNEY GENERAL OF CANADA Respondent AFFIDAVIT OF MURRAY SMITH Table of Contents A. Background 3 B. The Firearms Reference Table 5 The Canadian Firearms Program (CFP): 5 The Specialized Firearms Support Services (SFSS): 5 The Firearms Reference Table (FRT): 5 Updates to the FRT in light of the Regulation 6 Notice to the public about the Regulation 7 C. Variants 8 The Nine Families 8 Variants 9 D. Bore diameter and muzzle energy limit 12 Measurement of bore diameter: 12 The parts of a firearm 13 The measurement of bore diameter for shotguns 15 The measurement of bore diameter for rifles 19 Muzzle Energy 21 E. Non-prohibited firearms currently available for hunting and shooting 25 Hunting 25 Sport shooting 27 F. Examples of firearms used in mass shooting events in Canada that are prohibited by the Regulation 29 2 I, Murray Smith, of Ottawa, Ontario, do affirm THAT: A. Background 1. I am a forensic scientist with 42 years of experience in relation to firearms. 2. I was employed by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (“RCMP”) during the period of 1977 to 2020. I held many positions during that time, including the following: a. from 1989 to 2002,1 held the position of Chief Scientist responsible for the technical policy and quality assurance of the RCMP forensic firearms service, and the provision of technical advice to the government and police policy centres on firearms and other weapons; and b. -

Auction #129 - Two-Day Sale, March 27Th & 28Th 03/27/2021 9:00 AM EST

Auction - Auction #129 - Two-Day Sale, March 27th & 28th 03/27/2021 9:00 AM EST Lot Title/Description Lot Title/Description 1 Superb U.S. Remington Model 1863 Percussion Zouave Rifle 4 Fine New England Underhammer Percussion Sporting Rifle .58 caliber, 33" round barrel with a bright perfect bore. While most .30 caliber, 20'' octagon barrel with a very good bore and turned for Zouave rifles remain in fine condition, this example is exceptionally fine. starter at muzzle. This walnut stocked rifle is German silver mounted The barrel retains about 95% original blue finish with the slightest and engraved but oddly is not maker marked. Both David Squier and the amount of light flaking where the blue is starting to mix with a brown man from whom he purchased this rifle, Albert C. Mayer attribute it to patina. The lock and hammer retain 99% brilliant original color David Hilliard of Cornish, NH. It very much Hilliard's style and quality but case-hardened finish. The stock shows 98% of its original oil finish with at the end of the day it stands on its own merits regardless of its maker. nice raised grain feel throughout; both cartouches are very crisp. The The barrel shows areas of light scroll engraving at the breech, center brass patchbox, buttplate, barrel bands and forend tip all show a and muzzle as well as on the top tang of the buttplate. As mentioned it is pleasing mellow patina. The band retaining springs retain nearly all of German silver mounted with its round patchbox showing a very their original blue. -

Arts, Culture, and Economic Prosperity in Greater Philadelphia

arts culture & economic prosperity in Greater Philadelphia Peggy Amsterdam, President Greater Philadelphia Cultural Alliance One of the most frequent requests to the Greater Philadelphia Cultural Alliance is for the economic impact of the region’s cultural sector. It is with great pleasure, then, that we present Arts, Culture, and Economic Prosperity in Greater Philadelphia, the latest data available regarding the economic activity of our region’s nonprofit arts and cultural organizations and their audiences. This report is the result of collaboration among many partners, including Americans for the Arts, the Pennsylvania Cultural Data Project (PACDP), Metropolitan Philadelphia Indicators Project, and Drexel University’s Arts Administration Graduate Program. We thank the cultural organizations whose participation in the PACDP made this report possible, in particular those who allowed us to survey their audience members. We are also grateful to The Pew Charitable Trusts and the William Penn Foundation for their support of the Cultural Alliance, and to Tom Scannepieco and 1706 Rittenhouse Associates for supporting the design, printing, and distribution of this report. We express sincere gratitude to our external reviewers, board of directors, and staff, who guided the work through its inception and development. Much growth has occurred in our sector over the last decade. Through the information, analysis, and tools contained within this report, we trust that Arts, Culture, and Economic Prosperity in Greater Philadelphia will help us all in the quest to continue building an ever-stronger, more vibrant region. Tom Scannapieco, Partner Joe Zuritsky, Partner 1706 Rittenhouse Square Associates Over the past decade, Greater Philadelphia has experienced remarkable growth. -

Henry Chapman Mercer Fact Sheet

Henry Chapman Mercer Fact Sheet Henry Chapman Mercer (1856-1930) a noted tile-maker, archaeologist, antiquarian, artist and writer, was a leader in the turn-of-the-century Arts and Crafts Movement. ● Henry Chapman Mercer was born in Bucks County, Pennsylvania in 1856 and died at his home, Fonthill, in Doylestown in 1930. ● After graduating from Harvard in 1879, he was one of the founding members of The Bucks County Historical Society in 1880. ● He studied law at The University of Pennsylvania and was admitted to the Philadelphia bar. Mercer never practiced law but turned his interests towards a career in pre-historic archaeology. ● From 1894 to 1897, Mercer was Curator of American and Pre-historic Archaeology at The University of Pennsylvania Museum, Philadelphia. ● As an archaeologist, he conducted site excavations in the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico, and in the Ohio, Delaware, and Tennessee River valleys. ● In 1897, Mercer became interested in and began collecting "above ground" archaeological evidence of pre-industrial America. ● In searching out old Pennsylvania German pottery for his collection, Mercer developed a keen interest in the craft. By 1899 he was producing architectural tiles that became world famous. ● At fifty-two Mercer began building the first of three concrete structures: Fonthill, 1908-10, his home; the Moravian Pottery and Tile Works, 1910-12, his tile factory; and The Mercer Museum, 1913-16, which housed his collection of early American artifacts. ● Mercer authored Ancient Carpenters Tools and The Bible In Iron. ● Fond of animals and birds, Mercer developed a large arboretum with plants native to Pennsylvania on the grounds of Fonthill. -

Ming China As a Gunpowder Empire: Military Technology, Politics, and Fiscal Administration, 1350-1620 Weicong Duan Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations Arts & Sciences Winter 12-15-2018 Ming China As A Gunpowder Empire: Military Technology, Politics, And Fiscal Administration, 1350-1620 Weicong Duan Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds Part of the Asian History Commons, and the Asian Studies Commons Recommended Citation Duan, Weicong, "Ming China As A Gunpowder Empire: Military Technology, Politics, And Fiscal Administration, 1350-1620" (2018). Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1719. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds/1719 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts & Sciences at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY Dissertation Examination Committee: Steven B. Miles, Chair Christine Johnson Peter Kastor Zhao Ma Hayrettin Yücesoy Ming China as a Gunpowder Empire: Military Technology, Politics, and Fiscal Administration, 1350-1620 by Weicong Duan A dissertation presented to The Graduate School of of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2018 St. Louis, Missouri © 2018, -

CONNECTING to COLLECTIONS PENNSYLVANIA a Five-Year Preservation Plan for Pennsylvania PROJECT OVERVIEW

CONNECTING TO COLLECTIONS PENNSYLVANIA a five-year preservation plan for Pennsylvania PROJECT OVERVIEW Imagining Our Future: Preserving Pennsylvania’s Collections, published in August 2009, includes an in-depth analysis of conditions and needs at Pennsylvania’s collecting institutions, a detailed preservation plan to improve collections care throughout the state, and a five-year implementation timetable (2010-2015). The analysis concludes that many of Pennsylvania’s most important historic holdings must be considered at risk. Millions of items comprise these collections, and the financial resources available to care for them are limited and shrinking. Pennsylvania is a state vibrant with world-class art museums, libraries, historic sites. Arts and culture play a substantial role in creating business, jobs, and bringing revenue into the state and stewardship of its artifacts is too important —to the state, to the people, to the history of country—to be ignored. This call to action is a rallying cry for all future generations of Pennsylvanians. With generous support from the Institute of Museum and Library Services, and in close partnership with three leading preservation organizations, the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission (PHMC), the Pennsylvania Federation of Museums and Historical Organizations (PFMHO), and LYRASIS, the Conservation Center for Arts & Historic Artifacts organized and led the assessment and planning process. The project was capably guided by a Task Force with representatives from the Office of (PA) Commonwealth Libraries, the Western Pennsylvania Museum Council, the Pennsylvania Caucus of the Mid- Atlantic Regional Archives Conference, Pennsylvania State University, the Philadelphia Area Consortium of Special Collections Libraries, the University of Pittsburgh, and Carnegie Mellon University. -

The Wickham Musket Brochure

A Musket in a Privy (Text by Jan K. Herman) Fig. 1: A Musket in a Privy (not to scale: ALEXANDRIA ARCHAEOLOGY COLLECTION). To the casual observer who first saw it emerge from the privy muck on a humid June day in 1978, the battered and rusty firearm resembled little more than a scrap of refuse. The waterlogged stock was as coal black as the mud that tenaciously clung to it; corrosion and ooze obscured much of the barrel and lock. What was plainly visible and highly tantalizing to the archaeologists on the scene was the shiny, black flint tightly gripped in the jaws of the gun’s cocked hammer. At the time, no one could guess that many months of work would be required before the musket’s fascinating story could be told. Recovery: The musket’s resting place was a brick-lined shaft containing black fecal material and artifacts datable to the last half of the 19th century (see Site Map [link to “Site Map” in \\sitschlfilew001\DeptFiles\Oha\Archaeology\SHARED\Amanda - AX 1\Web]). Vertically imbedded in the sediments muzzle down, the gun resembled a chunk of waterlogged timber. It was in two pieces, fractured at the wrist. The archaeologist on the scene wrapped the two fragments in wet terry cloth, and once in the Alexandria Archaeology lab, the parts were sealed in polyethylene sheeting to await Fig. 2: “Feature QQ,” the privy where the musket was conservation. found (ALEXANDRIA ARCHAEOLOGY COLLECTION) Conservation Preliminary study revealed a military firearm of early 19th century vintage with the metal components badly corroded. -

An Examination of Flintlock Components at Fort St. Joseph (20BE23), Niles, Michigan

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 4-2019 An Examination of Flintlock Components at Fort St. Joseph (20BE23), Niles, Michigan Kevin Paul Jones Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Jones, Kevin Paul, "An Examination of Flintlock Components at Fort St. Joseph (20BE23), Niles, Michigan" (2019). Master's Theses. 4313. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/4313 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN EXAMINATION OF FLINTLOCK COMPONENTS AT FORT ST. JOSEPH (20BE23), NILES, MICHIGAN by Kevin P. Jones A thesis submitted to the Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Anthropology Western Michigan University April 2019 Thesis Committee: Michael S. Nassaney, Ph.D., Chair José A. Brandão, Ph.D. Amy S. Roache-Fedchenko, Ph.D. Copyright by Kevin P Jones 2019 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I want to thank my Mom and Dad for everything they do, have done, and will do to help me succeed. Thanks to my brothers and sister for so often leading by example. Also to Rod Watson, Ihsan Muqtadir, Shabani Mohamed Kariburyo, and Vinay Gavirangaswamy – friends who ask the tough questions, like “are you done yet?” I want to thank advisers and supporters from past and present. Dr. Kory Cooper, for setting me out on this path; Kathy Atwell for providing me an opportunity to start; my professors and advisers for this project for allowing it to happen; and Lauretta Eisenbach for making things happen. -

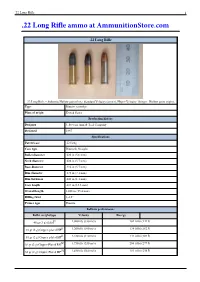

22 Long Rifle Ammo at Ammunitionstore.Com

.22 Long Rifle 1 .22 Long Rifle ammo at AmmunitionStore.com .22 Long Rifle .22 Long Rifle – Subsonic Hollow point (left). Standard Velocity (center), Hyper-Velocity "Stinger" Hollow point (right). Type Rimfire cartridge Place of origin United States Production history Designer J. Stevens Arm & Tool Company Designed 1887 Specifications Parent case .22 Long Case type Rimmed, Straight Bullet diameter .222 in (5.6 mm) Neck diameter .226 in (5.7 mm) Base diameter .226 in (5.7 mm) Rim diameter .278 in (7.1 mm) Rim thickness .043 in (1.1 mm) Case length .613 in (15.6 mm) Overall length 1.000 in (25.4 mm) Rifling twist 1–16" Primer type Rimfire Ballistic performance Bullet weight/type Velocity Energy [] 40 gr (3 g) Solid 1,080 ft/s (330 m/s) 104 ft·lbf (141 J) [] 38 gr (2 g) Copper-plated HP 1,260 ft/s (380 m/s) 134 ft·lbf (182 J) [] 31 gr (2 g) Copper-plated HP 1,430 ft/s (440 m/s) 141 ft·lbf (191 J) [1] 30 gr (2 g) Copper-Plated RN 1,750 ft/s (530 m/s) 204 ft·lbf (277 J) [1] 32 gr (2 g) Copper-Plated HP 1,640 ft/s (500 m/s) 191 ft·lbf (259 J) .22 Long Rifle 2 [][1] Source(s): The .22 Long Rifle rimfire (5.6×15R – metric designation) cartridge is a long established variety of ammunition, and in terms of units sold is still by far the most common in the world today. The cartridge is often referred to simply as .22 LR ("twenty-two-/ˈɛl/-/ˈɑr/") and various rifles, pistols, revolvers, and even some smoothbore shotguns have been manufactured in this caliber. -

PACIFIC DISTRICT Sons of the American Revolution Offering A

PACIFIC DISTRICT Sons of the American Revolution Offering a 1777 Charleville Musket Sep 1, 2014 to April 25, 2015 The Pacific District of the Sons of the American Revolution offers tickets on a drawing for an original 1777 Charleville AN IX flintlock musket. The Charleville muskets were used in large numbers by American Colonists and French troops fighting the British - the French arms that saved the American Revolution. There will be no more than 500 raffle tickets sold at $5.00 each.. Refurbished to 1777 standards by: -Col. Bob Smalser, Restoration Gunsmith This beautiful French Charleville Model 1777 restored musket with bayonet is a good example of a main infantry weapon of the Revolutionary War. Seven million were made between 1777 and 1840. Not a reproduction, but an original 1777 AN IX ca1810 with new European walnut stock, new 66 cal. barrel, assembled in the 1950’s in Liege, Belgium and refurbished to original armory standards. A brass flash guard is fitted over the pan and touch-hole and a leather sling is attached. Five feet long without the bayonet, and six feet four with. The piece was test-fired by gunsmith Bob Smalser of WASSAR. Retail value $1,200.00 Ticket purchase information Tickets will be sold by the Pacific District SAR at all ORSSAR, WASSAR, and AKSSAR individual chapter meetings during Sep 1, 2014 to Apr 25, 2015. You may also buy your tickets with a check made out to Pacific District SAR using the order form below. You may copy this page and buy as many tickets as you like.