Technology and Military Doctrine Essays on a Challenging Relationship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

If You Shed a Tear Part 2

“IF YOU SHED A TEAR" PART 2 Unveiling of the permanent Cenotaph in Whitehall by His Majesty King George V, 11 ovember 1920 THIS SECTIO COVERS THE PROFILES OF OUR FALLE 1915 TO 1917 “IF YOU SHED A TEAR" CHAPTER 9 1915 This was the year that the Territorial Force filled the gaps in the Regular’s ranks caused by the battles of 1914. They also were involved in new campaigns in the Middle East. COPPI , Albert Edward . He served as a Corporal with service number 7898 in the 1st Battalion of the Suffolk Regiment 84th Brigade, 28th Di vision Date of Death: 09/02/1915.His next of kin was given as Miss F. J. Coppin, of "Grasmere," Church Rd., Clacton -on-Sea, Essex. The CD "Soldiers Died in the Great War" shows that he was born in Old Heath & enlisted at Woolwich. Albert was entitled to the British War Medal and the Allied Victory Medal. He also earned the 1914-1915 Star At the outbreak of war, the 1st Battalion were in Khartoum, Sudan. On 20 ov 1907 they had set sail for Malta, arriving there on 27 ov. On 25 Ja n 1911 they went from Malta to Alexandria, arriving in Alexandria on 28 Jan. On 23 Jan 1912 they went from Alexandria to Cairo. In Feb 1914 they went from Cairo to Khartoum, where they were stationed at the outbreak of World War One. In Sept 1914 the 1st B attalion were ordered home, and they arrived in Liverpool on 23 Oct 1914. They then went to Lichfield, Staffs before going to Felixstowe on 17 ov 1914 (they were allotted to 28th Div under Major Gen E S Bulfin). -

The Foundations of US Air Doctrine

DISCLAIMER This study represents the views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the Air University Center for Aerospace Doctrine, Research, and Education (CADRE) or the Department of the Air Force. This manuscript has been reviewed and cleared for public release by security and policy review authorities. iii Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Watts, Barry D. The Foundations ofUS Air Doctrine . "December 1984 ." Bibliography : p. Includes index. 1. United States. Air Force. 2. Aeronautics, Military-United States. 3. Air warfare . I. Title. 11. Title: Foundations of US air doctrine . III. Title: Friction in war. UG633.W34 1984 358.4'00973 84-72550 355' .0215-dc 19 ISBN 1-58566-007-8 First Printing December 1984 Second Printing September 1991 ThirdPrinting July 1993 Fourth Printing May 1996 Fifth Printing January 1997 Sixth Printing June 1998 Seventh Printing July 2000 Eighth Printing June 2001 Ninth Printing September 2001 iv THE AUTHOR s Lieutenant Colonel Barry D. Watts (MA philosophy, University of Pittsburgh; BA mathematics, US Air Force Academy) has been teaching and writing about military theory since he joined the Air Force Academy faculty in 1974 . During the Vietnam War he saw combat with the 8th Tactical Fighter Wing at Ubon, Thailand, completing 100 missions over North Vietnam in June 1968. Subsequently, Lieutenant Colonel Watts flew F-4s from Yokota AB, Japan, and Kadena AB, Okinawa. More recently, he has served as a military assistant to the Director of Net Assessment, Office of the Secretary of Defense, and with the Air Staff's Project CHECKMATE. -

From August, 1861, to November, 1862, with The

P. R. L. P^IKCE, L I E E A E T. -42 4 5i f ' ' - : Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from The Institute of Museum and Library Services through an Indiana State Library LSTA Grant http://www.archive.org/details/followingflagfro6015coff " The Maine boys did not fire, but had a merry chuckle among themselves. Page 97. FOLLOWING THE FLAG. From August, 1861, to November, 1862, WITH THE ARMY OF THE POTOMAC. By "CARLETON," AUTHOR OF "MY DAYS AND NIGHTS ON THE BATTLE-FIELD.' BOSTON: TICKNOR AND FIELDS. 1865. Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1864, by CHARLES CARLETON COFFIN, in the Clerk's Office of the District Court for the District of Massachusetts. University Press: Welch, Bigelow, and Company, Cambridge. PREFACE. TT will be many years before a complete history -*- of the operations of the armies of the Union can be written ; but that is not a sufficient reason why historical pictures may not now be painted from such materials as have come to hand. This volume, therefore, is a sketch of the operations of the Army of the Potomac from August, 1861, to November, 1862, while commanded by Gener- al McOlellan. To avoid detail, the organization of the army is given in an Appendix. It has not been possible, in a book of this size, to give the movements of regiments ; but the narrative has been limited to the operations of brigades and di- visions. It will be comparatively easy, however, for the reader to ascertain the general position of any regiment in the different battles, by con- sulting the Appendix in connection with the narrative. -

Cartel, Code, and Consequences At

May 7, 2015 Eric Leonard General Orders No. 5-15 May 2015 CARTEL, CODE, AND CONSEQUENCES AT ANDERSONVILLE IN THIS ISSUE MCWRT News …………………………..… page 2 I have read in my earlier years about prisoners in the revolutionary war, and other wars. It sounded Announcements ……..………………….. page 3 noble and heroic to be a prisoner of war, and accounts of their adventures were quite romantic; but Coming Events ……………………………. page 4 the romance has been knocked out of the prisoner of war business, higher than a kite. It’s a fraud. Sesquicentennial News ………….. pages 5-6 John L. Ransom - Brigade Quartermaster From the Field ……………..……..... pages 7-8 9th Michigan Cavalry and prisoner at Andersonville 2015 Great Lakes Forum …………….. page 8 At Andersonville prison alone, nearly 13,000 men died over 14 months – an Wanderings ………………………………... page 9 average of more than 30 a day. Overall, 30,000 Union and 26,000 Confederate Meeting Reservation Form …….… page 10 soldiers died in captivity. Deaths at Andersonville represented 29% of the prison population. The death rate at the North’s prison in Elmira had a 24% death rate Between the Covers .……….… pages 10-11 with 3,000 dead, many due to illness. In Memoriam ……………………………. page 11 Quartermaster’s Regalia …………… page 12 Historians continue to debate whether the conditions in Civil War prisons were the result of insufficient resources and mismanagement or something more May Meeting at a Glance insidious – retaliation and deliberate cruelty. Our May speaker is clear on this Wisconsin Club issue: “We did this to ourselves.” th 9 and Wisconsin Avenue In his presentation to our Round Table, Eric Leonard will speak to us about [Jackets required for the dining room.] how the challenge of managing military prisoners took both sides by surprise at 5:30 p.m. -

The Evolution of British Tactical and Operational Tank Doctrine and Training in the First World War

The evolution of British tactical and operational tank doctrine and training in the First World War PHILIP RICHARD VENTHAM TD BA (Hons.) MA. Thesis submitted for the award of the degree of Master of Philosophy by the University of Wolverhampton October 2016 ©Copyright P R Ventham 1 ABSTRACT Tanks were first used in action in September 1916. There had been no previous combat experience on which to base tactical and operational doctrine for the employment of this novel weapon of war. Training of crews and commanders was hampered by lack of vehicles and weapons. Time was short in which to train novice crews. Training facilities were limited. Despite mechanical limitations of the early machines and their vulnerability to adverse ground conditions, the tanks achieved moderate success in their initial actions. Advocates of the tanks, such as Fuller and Elles, worked hard to convince the sceptical of the value of the tank. Two years later, tanks had gained the support of most senior commanders. Doctrine, based on practical combat experience, had evolved both within the Tank Corps and at GHQ and higher command. Despite dramatic improvements in the design, functionality and reliability of the later marks of heavy and medium tanks, they still remained slow and vulnerable to ground conditions and enemy counter-measures. Competing demands for materiel meant there were never enough tanks to replace casualties and meet the demands of formation commanders. This thesis will argue that the somewhat patchy performance of the armoured vehicles in the final months of the war was less a product of poor doctrinal guidance and inadequate training than of an insufficiency of tanks and the difficulties of providing enough tanks in the right locations at the right time to meet the requirements of the manoeuvre battles of the ‘Hundred Days’. -

Applying Traditional Military Principles to Cyber Warfare

2012 4th International Conference on Cyber Confl ict Permission to make digital or hard copies of this publication for internal use within NATO and for personal or educational use when for non-profi t or non-commercial C. Czosseck, R. Ottis, K. Ziolkowski (Eds.) purposes is granted providing that copies bear this notice and a full citation on the 2012 © NATO CCD COE Publications, Tallinn first page. Any other reproduction or transmission requires prior written permission by NATO CCD COE. Applying Traditional Military Principles to Cyber Warfare Samuel Liles Marcus Rogers Cyber Integration and Information Computer and Information Operations Department Technology Department National Defense University iCollege Purdue University Washington, DC West Lafayette, IN [email protected] [email protected] J. Eric Dietz Dean Larson Purdue Homeland Security Institute Larson Performance Engineering Purdue University Munster, IN West Lafayette, IN [email protected] [email protected] Abstract: Utilizing a variety of resources, the conventions of land warfare will be analyzed for their cyber impact by using the principles designated by the United States Army. The analysis will discuss in detail the factors impacting security of the network enterprise for command and control, the information conduits found in the technological enterprise, and the effects upon the adversary and combatant commander. Keywords: cyber warfare, military principles, combatant controls, mechanisms, strategy 1. INTRODUCTION Adams informs us that rapid changes due to technology have increasingly effected the affairs of the military. This effect whether economic, political, or otherwise has sometimes been extreme. Technology has also made substantial impacts on the prosecution of war. Adams also informs us that information technology is one of the primary change agents in the military of today and likely of the future [1]. -

Soldiers and Statesmen

, SOLDIERS AND STATESMEN For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price $2.65 Stock Number008-070-00335-0 Catalog Number D 301.78:970 The Military History Symposium is sponsored jointly by the Department of History and the Association of Graduates, United States Air Force Academy 1970 Military History Symposium Steering Committee: Colonel Alfred F. Hurley, Chairman Lt. Colonel Elliott L. Johnson Major David MacIsaac, Executive Director Captain Donald W. Nelson, Deputy Director Captain Frederick L. Metcalf SOLDIERS AND STATESMEN The Proceedings of the 4th Military History Symposium United States Air Force Academy 22-23 October 1970 Edited by Monte D. Wright, Lt. Colonel, USAF, Air Force Academy and Lawrence J. Paszek, Office of Air Force History Office of Air Force History, Headquarters USAF and United States Air Force Academy Washington: 1973 The Military History Symposia of the USAF Academy 1. May 1967. Current Concepts in Military History. Proceedings not published. 2. May 1968. Command and Commanders in Modem Warfare. Proceedings published: Colorado Springs: USAF Academy, 1269; 2d ed., enlarged, Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1972. 3. May 1969. Science, Technology, and Warfare. Proceedings published: Washington, b.C.: Government Printing Office, 197 1. 4. October 1970. Soldiers and Statesmen. Present volume. 5. October 1972. The Military and Society. Proceedings to be published. Views or opinions expressed or implied in this publication are those of the authors and are not to be construed as carrying official sanction of the Department of the Air Force or of the United States Air Force Academy. -

Air University Review: May-June 1984, Volume XXXV, No. 4

The Professional Journal of the United States Hovv lhe Army got its AirLand Batile Who should conirol air assets in the Clausewitz, Jomini, Douhet, concept—page 4 AirLand Batile?—page 16 and Brodie—How are they linked to our curreni nuclear posture? Should vve move now to ballistic missile defense?— page 54 Attendon The Air University Review is the professional journal of the United States Air Force and serves as an open forum for exploratory discussion. Its purpose is to present innovative thinking concerning Air Force doctrine, strategy, tactics, and related national defense matters. The Review should not be construed as representing policies of the Department of Defense, the Air Force, or Air University. Rather, the contents reflect the authors’ ideas and do not necessarily bear official sanction. Thought- ful and informed contributions are always welcomed. Al R UNIVERSITYrcuicw May-June 1984 Vol XXXV, No 4 2 T he Next War Editorial 4 T he Evoli tion of the Air L and Battle Concept John L. Romjue 16 T acair Si ppo r t for Air L and Battle Maj. James A. Machos, USAF 25 T he Q i est for Unitv of Comma nd Col. Thomas A. Cardvvell 111, USAF 30 I ra C. Eaker Essav Competition Second-Prize Win n er L eaüer ship to Match O i r T echnologv Lt. Col. Harry R. Borowski, USAF 35 EQL ALITV IN THE COCKPIT Li. Col. Nancy B. Samuelson, USAF 47 T he Air Forc:e Wif e— H er Per spect ive Maj. Mark M. Warner, USAF Differing views and provocaiive 54 C lassical Mil it a r v Stratecy and quesuons on the nuclear issues oí Ballistic Miss il e Defense lhe 1980s—page 81 Maj. -

MILITARY DOCTRINE in INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS STRATEGY for the ARAB COUNTRIES and the BIG POWERS Dr. Mohamamd Salim Al-Rawashdeh

International Journal of International Relations, Media and Mass Communication Studies Vol.2, No.1, pp.30-62, March 2016 ___Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org) MILITARY DOCTRINE IN INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS STRATEGY FOR THE ARAB COUNTRIES AND THE BIG POWERS Dr. Mohamamd Salim Al-Rawashdeh Associated professor, International Relations, Al-Balqa’a Applied University, Jordan. The Royal College for Staff and Command and National Defense, Bahrain Defense Force, Kingdom of Bahrain. ABSTRACT: (All Life is readiness for a huge thing that may not happen at all). The military doctrine is the basic concept for the security of the State concerned, also seeks to formulate goals and tasks of the military policy of the state, and the identification of priority interests, and to express its position on issues of war and areas of use of military force and the drafting of combat missions assigned to the forces of the state in time of war or peace, and the diagnosis of the nature of the actual and potential military threats against the state, and the nature of future war that can be plugged in the state, as well as for characterization methods by which to repel any aggression by military means, and to develop new concepts of military strategies, and guidance of preparation of the State for the purpose of defending the territory of the State and the safety of its soil. The differences between religious belief and military doctrine. Some people who were not familiar with the term "military doctrine" that this term is given by a specific researcher or some academics or that the use of metaphor for the phrase "doctrine", or something else similar; but many interested readers know that the military doctrine or army dogma as it is known, in some countries in the world is the basis corner for the definition of a army and military force. -

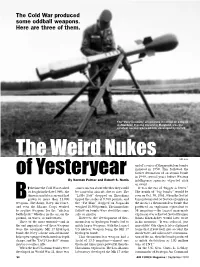

The Weird Nukes of Yesteryear

The Cold War produced some oddball weapons. Here are three of them. The “Davy Crockett,” shown here mounted on a tripod at Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland, was the smallest nuclear warhead ever developed by the US. The Weird Nukes DOD photo end of a series of thermonuclear bombs initiated in 1950. This followed the Soviet detonation of an atomic bomb of Yesteryear in 1949, several years before Western By Norman Polmar and Robert S. Norris intelligence agencies expected such an event. y the time the Cold War reached some concern about whether they could It was the era of “bigger is better.” its height in the late 1960s, the be carried in aircraft, due to size. The The zenith of “big bombs” would be American nuclear arsenal had “Little Boy” dropped on Hiroshima seen on Oct. 30, 1961, when the Soviet grown to more than 31,000 tipped the scales at 9,700 pounds, and Union detonated (at Novaya Zemlya in Bweapons. The Army, Navy, Air Force, the “Fat Man” dropped on Nagasaki the Arctic) a thermonuclear bomb that and even the Marine Corps worked weighed 10,300 pounds. The immediate produced an explosion equivalent to to acquire weapons for the “nuclear follow-on bombs were about the same 58 megatons—the largest man-made battlefield,” whether in the air, on the size or smaller. explosion ever achieved. Soviet Premier ground, on water, or underwater. However, the development of ther- Nikita Khrushchev would later write Three of the more unusual—and in monuclear or hydrogen bombs led to in his memoirs: “It was colossal, just the end impractical—of these weapons much larger weapons, with the largest incredible! Our experts later explained were the enormous Mk 17 hydrogen US nuclear weapon being the Mk 17 to me that if you took into account the bomb, the Navy’s drone anti-submarine hydrogen bomb. -

42, the Erosion of Civilian Control Of

'The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the US Air Force, Department of Defense or the US Government.'" UNITED STATES AIR FORCE ACADEMY Develops and inspires air and space leaders with vision for tomorrow. The Erosion of Civilian Control of the Military in the United States Today Richard H. Kohn University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill The Harmon Memorial Lectures in Military History Number Forty-Two United States Air Force Academy Colorado 1999 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402 Lieutenant General Hubert Reilly Harmon Lieutenant General Hubert R. Harmon was one of several distinguished Army officers to come from the Harmon family. His father graduated from the United States Military Academy in 1880 and later served as Commandant of Cadets at the Pennsylvania Military Academy. Two older brothers, Kenneth and Millard, were members of the West Point class of 1910 and 1912, respectively. The former served as Chief of the San Francisco Ordnance District during World War II; the latter reached flag rank and was lost over the Pacific during World War II while serving as Commander of the Pacific Area Army Air Forces. Hubert Harmon, born on April 3, 1882, in Chester, Pennsylvania, followed in their footsteps and graduated from the United States Military Academy in 1915. Dwight D. Eisenhower also graduated in this class, and nearly forty years later the two worked together to create the new United States Air Force Academy. Harmon left West Point with a commission in the Coast Artillery Corps, but he was able to enter the new Army air branch the following year. -

On the Western Front, 1915-18

WAITING FOR THE 'G' A RE-EVALUATION OF THE ROLE OF THE BRITISH CAVALRY ON THE WESTERN FRONT, 1915-18 b~ MAJOR RICHARD L. BOWES A thesis submitted to the War Studies Cornmittee of the Royal hlilitary College of Canada in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Royal MSîtary Coliege of Canada Kingston, Ontario 20 May 2000 Copyright Q Richard Bowes, 2000 National Libfary Bibliothèque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 WeUington çtieet 395. nie Wellington Ottawa ON KtAON4 OîîawaON KlAûN4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Lïbmy of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, districbute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microfom, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la fome de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or othexwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. 1 would like to acknowledge rny indebtedness to the many personalities who supported and assisted me in the writing of this thesis. Of course, 1 would like to thank my thesis supervisor, Dr. Ron Haycock, who graciously took time out of his busy schedule as Dean of Arts at the Royal Military College of Canada to take on the extra responsibility of providing me with guidance and support throughout the research and writing phases of my journey.