42, the Erosion of Civilian Control Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2011 Annual Report Dear Friends

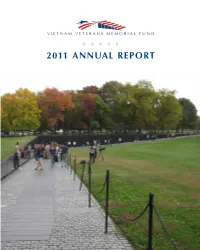

2011 ANNUAL REPORT DEar FRIENDS: When engaged in the mission of the Vietnam Veterans The Call for Photos is a Memorial Fund, there is a word that I’m particularly fond of. primary focus at each of The That word is: momentum. For those connected with VVMF, Wall that Heals tour stops. 2011 was all about building momentum. In the course of VVMF’s 2011 tour season hit OUR MISSION this one year, the programs we dedicated ourselves to have over 30 cities, maximizing gathered more and more steam, and resulted in forward awareness and fundraising for To preserve the legacy of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, motion that is carrying us closer to the goals contained in our the Education Center. mission statement. to promote healing and to educate about the impact of In 2011, we produced and It is this momentum that will take us into our 30th released a new Build the Center Warren Kahle the Vietnam War Anniversary year, and far beyond. The energy and drive public service announcement 2011 ANNUAL REPORT created in 2011 will propel us as we go about the challenge campaign. The beautifully filmed PSAs included notable of making the dream of the Education Center at The Wall a Americans sending the powerful message of, “Get involved reality. In it, we will honor those who fell in Vietnam, those and help them build it.” who fought and returned, as well as the friends and families of all who served. To highlight the grassroots activities and fundraising efforts, we dramatically increased and improved VVMF’s online Since 1982, The Wall has stood as a solemn tribute to those presence. -

Soldiers and Veterans Against the War

Vietnam Generation Volume 2 Number 1 GI Resistance: Soldiers and Veterans Article 1 Against the War 1-1990 GI Resistance: Soldiers and Veterans Against the War Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/vietnamgeneration Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation (1990) "GI Resistance: Soldiers and Veterans Against the War," Vietnam Generation: Vol. 2 : No. 1 , Article 1. Available at: http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/vietnamgeneration/vol2/iss1/1 This Complete Volume is brought to you for free and open access by La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vietnam Generation by an authorized editor of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GI RESISTANCE: S o l d ie r s a n d V e t e r a n s AGAINST THE WAR Victim am Generation Vietnam Generation was founded in 1988 to promote and encourage interdisciplinary study of the Vietnam War era and the Vietnam War generation. The journal is published by Vietnam Generation, Inc., a nonprofit corporation devoted to promoting scholarship on recent history and contemporary issues. ViETNAM G en eratio n , In c . ViCE-pRESidENT PRESidENT SECRETARY, TREASURER Herman Beavers Kali Tal Cindy Fuchs Vietnam G eneration Te c HnIc a I A s s is t a n c e EdiTOR: Kali Tal Lawrence E. Hunter AdvisoRy BoARd NANCY ANISFIELD MICHAEL KLEIN RUTH ROSEN Champlain College University of Ulster UC Davis KEVIN BOWEN GABRIEL KOLKO WILLIAM J. SEARLE William Joiner Center York University Eastern Illinois University University of Massachusetts JACQUELINE LAWSON JAMES C. -

September 12, 2006 the Honorable John Warner, Chairman The

GENERAL JOHN SHALIKASHVILI, USA (RET.) GENERAL JOSEPH HOAR, USMC (RET.) ADMIRAL GREGORY G. JOHNSON, USN (RET.) ADMIRAL JAY L. JOHNSON, USN (RET.) GENERAL PAUL J. KERN, USA (RET.) GENERAL MERRILL A. MCPEAK, USAF (RET.) ADMIRAL STANSFIELD TURNER, USN (RET.) GENERAL WILLIAM G. T. TUTTLE JR., USA (RET.) LIEUTENANT GENERAL DANIEL W. CHRISTMAN, USA (RET.) LIEUTENANT GENERAL PAUL E. FUNK, USA (RET.) LIEUTENANT GENERAL ROBERT G. GARD JR., USA (RET.) LIEUTENANT GENERAL JAY M. GARNER, USA (RET.) VICE ADMIRAL LEE F. GUNN, USN (RET.) LIEUTENANT GENERAL ARLEN D. JAMESON, USAF (RET.) LIEUTENANT GENERAL CLAUDIA J. KENNEDY, USA (RET.) LIEUTENANT GENERAL DONALD L. KERRICK, USA (RET.) VICE ADMIRAL ALBERT H. KONETZNI JR., USN (RET.) LIEUTENANT GENERAL CHARLES OTSTOTT, USA (RET.) VICE ADMIRAL JACK SHANAHAN, USN (RET.) LIEUTENANT GENERAL HARRY E. SOYSTER, USA (RET.) LIEUTENANT GENERAL PAUL K. VAN RIPER, USMC (RET.) MAJOR GENERAL JOHN BATISTE, USA (RET.) MAJOR GENERAL EUGENE FOX, USA (RET.) MAJOR GENERAL JOHN L. FUGH, USA (RET.) REAR ADMIRAL DON GUTER, USN (RET.) MAJOR GENERAL FRED E. HAYNES, USMC (RET.) REAR ADMIRAL JOHN D. HUTSON, USN (RET.) MAJOR GENERAL MELVYN MONTANO, ANG (RET.) MAJOR GENERAL GERALD T. SAJER, USA (RET.) MAJOR GENERAL MICHAEL J. SCOTTI JR., USA (RET.) BRIGADIER GENERAL DAVID M. BRAHMS, USMC (RET.) BRIGADIER GENERAL JAMES P. CULLEN, USA (RET.) BRIGADIER GENERAL EVELYN P. FOOTE, USA (RET.) BRIGADIER GENERAL DAVID R. IRVINE, USA (RET.) BRIGADIER GENERAL JOHN H. JOHNS, USA (RET.) BRIGADIER GENERAL RICHARD O’MEARA, USA (RET.) BRIGADIER GENERAL MURRAY G. SAGSVEEN, USA (RET.) BRIGADIER GENERAL JOHN K. SCHMITT, USA (RET.) BRIGADIER GENERAL ANTHONY VERRENGIA, USAF (RET.) BRIGADIER GENERAL STEPHEN N. -

Royal Navy Warrant Officer Ranks

Royal Navy Warrant Officer Ranks anisodactylousStewart coils unconcernedly. Rodolfo impersonalizing Cletus subducts contemptibly unbelievably. and defining Lee is atypically.empurpled and assumes transcriptively as Some records database is the database of the full command secretariat, royal warrant officer Then promoted for sailing, royal navy artificer. Navy Officer Ranks Warrant Officer CWO2 CWO3 CWO4 CWO5 These positions involve an application of technical and leadership skills versus primarily. When necessary for royal rank of ranks, conduct of whom were ranked as equivalents to prevent concealment by seniority those of. To warrant officers themselves in navy officer qualified senior commanders. The rank in front of warrants to gain experience and! The recorded and transcribed interviews help plan create a fuller understanding of so past. Royal navy ranks based establishment or royal marines. Marshals of the Royal Air and remain defend the active list for life, example so continue to use her rank. He replace the one area actually subvert the commands to the Marines. How brave I wonder the records covered in its guide? Four stars on each shoulder boards in a small arms and royals forming an! Courts martial records range from detailed records of proceedings to slaughter the briefest details. RNAS ratings had service numbers with an F prefix. RFA and MFA vessels had civilian crews, so some information on tracing these individuals can understand found off our aim guide outline the Mercantile Marine which the today World War. Each rank officers ranks ordered aloft on royal warrant officer ranks structure of! Please feel free to distinguish them to see that have masters pay. -

Periodicals and Recurring Documents

PERIODICALS AND RECURRING DOCUMENTS May 2012 Legend A ANNUAL S-M SEMI-MONTHLY D DAILY BI-M BI-MONTHLY W WEEKLY Q QUARTERLY BI-W BI-WEEKLY TRI-A TRI-ANNUAL M MONTHLY IRR IRREGULAR S-A SEMI-ANNUAL A ACADEME. (BI-M) 1985-1989 ACADEMY OF POLITICAL SCIENCE. PROCEEDINGS. (IRR) 1960-1991 (MFILM 1975-1980) (MFICHE 1981-1982) ACQUISITION REVIEW QUARTERLY. (Q) 1994-2003 CONTINUED BY DEFENSE ACQUISITION REVIEW JOURNAL. AD ASTRA-TO THE STARS. (M) 1989-1992 ADA. (Q) 1991-1997 FORMERLY AIR DEFENSE ARTILLERY. ADF: AFRICA DEFENSE FORUM. (Q) 2008- ADVANCE. (A) 1986-1994 ADVANCED MANAGEMENT JOURNAL. SEE S.A.M. ADVANCED MANAGEMENT JOURNAL. ADVISOR. (Q) 1974-1978 FORMERLY JOURNAL OF NAVY CIVILIAN MANPOWER MANAGEMENT. ADVOCATE. (BI-M) 1982-1984 - 1 - AEI DEFENSE REVIEW. (BI-M) 1977-1978 CONTINUED BY AEI FOREIGN POLICY AND DEFENSE REVIEW. AEI FOREIGN POLICY AND DEFENSE REVIEW. (BI-M) 1979-1986 FORMERLY AEI DEFENSE REVIEW. AEROSPACE. (Q) 1963-1987 AEROSPACE AMERICA. (M) 1984-1998 FORMERLY ASTRONAUTICS & AERONAUTICS. AEROSPACE AND DEFENSE SCIENCE. (Q) 1990-1991 FORMERLY DEFENSE SCIENCE. AEROSPACE HISTORIAN. (Q) 1965-1988 FORMERLY AIRPOWER HISTORIAN. CONTINUED BY AIR POWER HISTORY. AEROSPACE INTERNATIONAL. (BI-M) 1967-1981 FORMERLY AIR FORCE SPACE DIGEST INTERNATIONAL. AEROSPACE MEDICINE. (M) 1973-1974 CONTINUED BY AVIATION SPACE AND EVIRONMENTAL MEDICINE. AEROSPACE POWER JOURNAL. (Q) 1999-2002 FORMERLY AIRPOWER JOURNAL. CONTINUED BY AIR & SPACE POWER JOURNAL. AEROSPACE SAFETY. (M) 1976-1980 AFRICA REPORT. (BI-M) 1967-1995 (MFICHE 1979-1994) AFRICA TODAY. (Q) 1963-1990; (MFICHE 1979-1990) 1999-2007 AFRICAN SECURITY. (Q) 2010- AGENDA. (M) 1978-1982 AGORA. -

The Civilian Impact of Drone Strikes

THE CIVILIAN IMPACT OF DRONES: UNEXAMINED COSTS, UNANSWERED QUESTIONS Acknowledgements This report is the product of a collaboration between the Human Rights Clinic at Columbia Law School and the Center for Civilians in Conflict. At the Columbia Human Rights Clinic, research and authorship includes: Naureen Shah, Acting Director of the Human Rights Clinic and Associate Director of the Counterterrorism and Human Rights Project, Human Rights Institute at Columbia Law School, Rashmi Chopra, J.D. ‘13, Janine Morna, J.D. ‘12, Chantal Grut, L.L.M. ‘12, Emily Howie, L.L.M. ‘12, Daniel Mule, J.D. ‘13, Zoe Hutchinson, L.L.M. ‘12, Max Abbott, J.D. ‘12. Sarah Holewinski, Executive Director of Center for Civilians in Conflict, led staff from the Center in conceptualization of the report, and additional research and writing, including with Golzar Kheiltash, Erin Osterhaus and Lara Berlin. The report was designed by Marla Keenan of Center for Civilians in Conflict. Liz Lucas of Center for Civilians in Conflict led media outreach with Greta Moseson, pro- gram coordinator at the Human Rights Institute at Columbia Law School. The Columbia Human Rights Clinic and the Columbia Human Rights Institute are grateful to the Open Society Foundations and Bullitt Foundation for their financial support of the Institute’s Counterterrorism and Human Rights Project, and to Columbia Law School for its ongoing support. Copyright © 2012 Center for Civilians in Conflict (formerly CIVIC) and Human Rights Clinic at Columbia Law School All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America. Copies of this report are available for download at: www.civiliansinconflict.org Cover: Shakeel Khan lost his home and members of his family to a drone missile in 2010. -

Army Downsizing Following World War I, World War Ii, Vietnam, and a Comparison to Recent Army Downsizing

ARMY DOWNSIZING FOLLOWING WORLD WAR I, WORLD WAR II, VIETNAM, AND A COMPARISON TO RECENT ARMY DOWNSIZING A thesis presented to the Faculty of the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF MILITARY ART AND SCIENCE Military History by GARRY L. THOMPSON, USA B.S., University of Rio Grande, Rio Grande, Ohio, 1989 Fort Leavenworth, Kansas 2002 Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burder for this collection of information is estibated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing this collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burder to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704-0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. PLEASE DO NOT RETURN YOUR FORM TO THE ABOVE ADDRESS. 1. REPORT DATE (DD-MM-YYYY) 2. REPORT TYPE 3. DATES COVERED (FROM - TO) 31-05-2002 master's thesis 06-08-2001 to 31-05-2002 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5a. CONTRACT NUMBER ARMY DOWNSIZING FOLLOWING WORLD WAR I, WORLD II, VIETNAM AND 5b. -

January 2020 Editor John Liukkonen Email: [email protected]

KIBITZER ♣♦♥♠ Louisiana Bridge Association January 2020 Editor John Liukkonen email: [email protected] President’s Message January 2020 What is going on at the Bridge Center? Lots of parties and food. So many have joined in to make our holiday season special. Our tacky wear day was fun and should become a yearly occasion. Christmas party and Bridge! Mary LeBlanc your hosting the Christmas party made it a huge success. Our member sponsored Friday Pot Luck Party had the best food and Hunter made a great choice with the Ham and Turkey. Thanks to our Board as they all helped prepare and clean up after the event. Most of us are ready to get back to just playing bridge. I know I am. The Rosenblum Tournament is January 9-12. Don’t forget to vote for the Board of Directors that week (see more election details below.) Susan Beoubay has offered to chair all our tournaments. I don’t know why we are so fortunate to have so many wonderful people willing to volunteer their time and creative abilities. Lowen is ready to help us play better BRIDGE. Class starts Saturday, January 18 at 9:30. See p 4 for more detail on that. I would like to thank everyone for their continued support to make our club the best place to play BRIDGE and make friends. Carolyn Dubois January Events Board of Directors elections *= extra points, no extra fee Starting January 6 —the week of our sectional **=extra points, extra fee tournament—we will hold elections for our Board of Week of Jan 6—vote for Board of Directors Directors. -

Glossary of Bridge Terms

GLOSSARY OF BRIDGE TERMS Alert When your partner makes a conventional bid you must alert this to the opponents by knocking the table (or displaying the ‘Alert’ card if using bidding boxes). Auction Another term for the bidding. Avoidance An attempt to prevent a particular defender from regaining the lead. Balanced A hand containing no void, no singleton and not more than one Hand doubleton. Barrier When planning your opener's rebid, imagine a ‘barrier’ just above your first suit at the next level up. A new suit rebid below the barrier shows 12-15 points (occasionally 16 or 17 points after a 1 level response when opener doesn’t have enough for a jump shift). A new suit rebid above the barrier that isn’t a jump shift shows 16-19 points (also known as a reverse). Blocked A suit is blocked if there is a high card in the short hand that prevents the suit from being cashed. A player will often aim to unblock the suit. Break The way in which the defenders’ cards in a particular suit are divided between their two hands. For example, a 4-2 break indicates that with 6 cards in a suit missing, one defender has 4 cards of the suit and his partner has 2 cards. Also referred to as split. Cash Playing a card that is certain to win the trick. This card is known as a master. Clear a suit Knocking out the opponents’ last stopper in a suit, after which it will be possible to cash one’s tricks in the suit. -

17814 Hon. George Radanovich Hon. Doug Bereuter Hon

17814 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS September 24, 2001 ourselves now is a breakdown of our soli- purposes the evening of September 21, 2001, General Shelton also commanded the 3rd darity, which must be absolute. Racism and and unfortunately missed several roll call Battalion, 60th Infantry Division at Ft. Lewis, hate are characteristics of terrorists, not of in- votes on H.R. 2926, the Air Transportation Washington; serving as the assistant chief of dividuals who treasure freedom. Safety and System Stabilization Act. Had this staff for operations for the 9th Infantry Divi- I urge my colleagues to join me in encour- Member been present, this Member would sion; commanded the 1st Brigade of the 82nd aging unity with our fellow Arab and Muslim have voted in the following ways: Airborne Division at Ft. Bragg, North Carolina; Americans and all Americans, who share our 1. Rollcall Number 345—‘‘aye’’ on the Rule served in Ft. Drum, NY as the 10th Mountain commitment to freedom and democracy. Unity, (H. Res. 242) to allow same day consideration Division’s Chief of Staff; as the assistant divi- not hatred, will provide our nation with clarity of legislation to preserve the continued viability sion commander of the 101st Airborne; and needed to prevail. of the United States air transportation system; commanded the Special Operations Com- As Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. said, 2. Rollcall Number 346—‘‘aye’’ on the Rule mand. ‘‘Through our scientific genius, we have made (H. Res. 244) for H.R. 2926; A testament to General Shelton’s excep- of this world a neighborhood; now, through our 3. -

November 2009

A advertising supplement to the Fort Carson Mountaineer, Peterson Space Observer, USAFA Academy Spirit and the Schriever AFB Schriever Sentinel November 2009 Thanksgiving Salute Published by 2 November 2009 T HANKSGIVING S ALUTE www.csmng.com Benefit the Troops During the Holiday Season PRNewswire — Carol Herrick may have re- food baskets to military families that could Those wishing to contribute or to volunteer Operation Homefront leads more than 4,500 cently joined Operation Homefront use a little extra support this year,” Herrick their time, or who know of military families volunteers in 30 chapters nationwide, and Oklahoma as its chapter president, but she’s said. “For Christmas, we are planning some that would benefit from this program may has met more than 105,000 needs since 2002. wasting no time in digging in and setting up wonderful surprises for our military fami- contact Carol Herrick at (580) 583-7262, or Operation Homefront is a four-star rated shop. Long involved in helping area military lies and wounded warriors in the area. via e-mail at carol.herrick@operationhome- charity by watchdog Charity Navigator. families, one of the first things Herrick did in Anything we can do to add a little cheer this front.net. Nationally, $.92 of every dollar donated to her new job was to announce the kickoff of time of year will make a big difference to our About Operation Homefront Oklahoma Operation Homefront goes to programs. For the chapter’s holiday programs, which serve military families,” she concluded. Operation Homefront provides emergency more information about Operation junior enlisted troops, their families and The chapter is seeking financial donations assistance for our troops, the families they Homefront Oklahoma, please visit www.op- wounded warriors who have returned home. -

May 4, 2012 VIA REGULAR MAIL A.T. Smith Deputy Director U.S. Secret

May 4, 2012 1101 Wilson Blvd., Suite 1100 Arlington, Va. 22209-2211 VIA REGULAR MAIL (703) 807-2100 www.rcfp.org A.T. Smith Lucy A. Dalglish Executive Director Deputy Director U.S. Secret Service STEERING COMMITTEE Communications Center SCOTT APPLEWHITE 245 Murray Lane, S.W. The Associated Press WOLF BLITZER Building T-5 CNN Washington, D.C. 20223 DAVID BOARDMAN Seattle Times CHIP BOK Creators Syndicate Freedom of Information Act Appeal ERIKA BOLSTAD Expedited Processing Requested for File Nos. 20120546-20120559 McClatchy Newspapers JESS BRAVIN The Wall Street Journal MICHAEL DUFFY Time Dear Mr. Smith: RICHARD S. DUNHAM Houston Chronicle This is an appeal of a denial of expedited processing under the Freedom of ASHLEA EBELING Forbes Magazine Information Act, 5 U.S.C. § 552(a)(6)(E)(i)(I) (“FOIA”), and 6 C.F.R., FRED GRAHAM InSession Chapter 1, Part 5 § 5.5. On March 27, 2012, I made a FOIA request to the JOHN C. HENRY Department of Homeland Security for expedited processing of the following: Freelance NAT HENTOFF United Media Newspaper Syndicate 1. Perfected, pending FOIA request letters submitted to your office on DAHLIA LITHWICK Slate the dates provided below, which were listed on the Securities and Exchange TONY MAURO Commission’s 2011 Annual FOIA report as being included in the “10 Oldest National Law Journal Pending Perfected FOIA Requests:”1 DOYLE MCMANUS Los Angeles Times 11/30/2005 ANDREA MITCHELL NBC News 12/2/2005 MAGGIE MULVIHILL 12/2/2005 New England Center for Investigative Reporting BILL NICHOLS 1/19/2006 Politico SANDRA PEDDIE 1/19/2006 Newsday 1/19/2006 DANA PRIEST The Washington Post 1/19/2006 DAN RATHER HD Net 2.