Danger Close: Military Politicization and Elite Credibility Michael Robinson United States Military Academy, [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2011 Annual Report Dear Friends

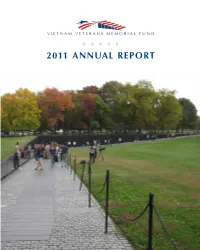

2011 ANNUAL REPORT DEar FRIENDS: When engaged in the mission of the Vietnam Veterans The Call for Photos is a Memorial Fund, there is a word that I’m particularly fond of. primary focus at each of The That word is: momentum. For those connected with VVMF, Wall that Heals tour stops. 2011 was all about building momentum. In the course of VVMF’s 2011 tour season hit OUR MISSION this one year, the programs we dedicated ourselves to have over 30 cities, maximizing gathered more and more steam, and resulted in forward awareness and fundraising for To preserve the legacy of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, motion that is carrying us closer to the goals contained in our the Education Center. mission statement. to promote healing and to educate about the impact of In 2011, we produced and It is this momentum that will take us into our 30th released a new Build the Center Warren Kahle the Vietnam War Anniversary year, and far beyond. The energy and drive public service announcement 2011 ANNUAL REPORT created in 2011 will propel us as we go about the challenge campaign. The beautifully filmed PSAs included notable of making the dream of the Education Center at The Wall a Americans sending the powerful message of, “Get involved reality. In it, we will honor those who fell in Vietnam, those and help them build it.” who fought and returned, as well as the friends and families of all who served. To highlight the grassroots activities and fundraising efforts, we dramatically increased and improved VVMF’s online Since 1982, The Wall has stood as a solemn tribute to those presence. -

The Civilian Impact of Drone Strikes

THE CIVILIAN IMPACT OF DRONES: UNEXAMINED COSTS, UNANSWERED QUESTIONS Acknowledgements This report is the product of a collaboration between the Human Rights Clinic at Columbia Law School and the Center for Civilians in Conflict. At the Columbia Human Rights Clinic, research and authorship includes: Naureen Shah, Acting Director of the Human Rights Clinic and Associate Director of the Counterterrorism and Human Rights Project, Human Rights Institute at Columbia Law School, Rashmi Chopra, J.D. ‘13, Janine Morna, J.D. ‘12, Chantal Grut, L.L.M. ‘12, Emily Howie, L.L.M. ‘12, Daniel Mule, J.D. ‘13, Zoe Hutchinson, L.L.M. ‘12, Max Abbott, J.D. ‘12. Sarah Holewinski, Executive Director of Center for Civilians in Conflict, led staff from the Center in conceptualization of the report, and additional research and writing, including with Golzar Kheiltash, Erin Osterhaus and Lara Berlin. The report was designed by Marla Keenan of Center for Civilians in Conflict. Liz Lucas of Center for Civilians in Conflict led media outreach with Greta Moseson, pro- gram coordinator at the Human Rights Institute at Columbia Law School. The Columbia Human Rights Clinic and the Columbia Human Rights Institute are grateful to the Open Society Foundations and Bullitt Foundation for their financial support of the Institute’s Counterterrorism and Human Rights Project, and to Columbia Law School for its ongoing support. Copyright © 2012 Center for Civilians in Conflict (formerly CIVIC) and Human Rights Clinic at Columbia Law School All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America. Copies of this report are available for download at: www.civiliansinconflict.org Cover: Shakeel Khan lost his home and members of his family to a drone missile in 2010. -

2011-Summer.Pdf

BOWDOIN MAGAZINE VOL. 82 NO. 2 SUMMER 2011 BV O L . 8 2 N Oow . 2 S UMMER 2 0 1 1 doin STANDP U WITH ASOCIAL FOR THECLASSOF1961, BOWDOINISFOREVER CONSCIENCE JILLSHAWRUDDOCK’77 HARI KONDABOLU ’04 SLICINGTHEPIEFOR THE POWER OF COMEDY AS AN STUDENTACTIVITIES INSTRUMENT FOR CHANGE SUMMER 2011 CONTENTS BowdoinMAGAZINE 24 AGreatSecondHalf PHOTOGRAPHS BY FELICE BOUCHER In an interview that coincided with the opening of an exhibition of the Victoria and Albert’s English alabaster reliefs at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art last semester, Jill Shaw Ruddock ’77 talks about the goal of her new book, The Second Half of Your Life—to make the second half the best half. 30 FortheClassof1961,BowdoinisForever BY LISA WESEL • PHOTOGRAHS BY BOB HANDELMAN AND BRIAN WEDGE ’97 After 50 years as Bowdoin alumni, the Class of 1961 is a particularly close-knit group. Lisa Wesel spent time with a group of them talking about friendship, formative experi- ences, and the privilege of traveling a long road together. 36 StandUpWithaSocialConscience BY EDGAR ALLEN BEEM • PHOTOGRAPHS BY KARSTEN MORAN ’05 The Seattle Times has called Hari Kondabolu ’04 “a young man reaching for the hand-scalding torch of confrontational comics like Lenny Bruce and Richard Pryor.” Ed Beem talks to Hari about his journey from Queens to Brunswick and the power of comedy as an instrument of social change. 44 SlicingthePie BY EDGAR ALLEN BEEM • PHOTOGRAPHS BY DEAN ABRAMSON The Student Activity Fund Committee distributes funding of nearly $700,000 a year in support of clubs, entertainment, and community service. -

PEACE by COMMITTEE Command and Control Issues in Multinational Peace Enforcement Operations

PEACE BY COMMITTEE Command and Control Issues in Multinational Peace Enforcement Operations HAROLD E. BULLOCK, Major, USAF School of Advanced Airpower Studies THESIS PRESENTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE SCHOOL OF ADVANCED AIRPOWER STUDIES, MAXWELL AIR FORCE BASE, ALABAMA, FOR COMPLETION OF GRADUATION REQUIREMENTS, ACADEMIC YEAR 93–94 Air University Press Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama February 1995 Disclaimer This publication was produced in the Department of Defense school environment in the interest of academic freedom and the advancement of national defense-related concepts. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense or the United States government. This publication has been reviewed by security and policy review authorities and is cleared for public release. ii Contents Chapter Page DISCLAIMER . ii ABSTRACT . v ABOUT THE AUTHOR . vii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS . ix 1 INTRODUCTION . 1 Notes . 2 2 COMMAND AND FORCE STRUCTURE . 3 Dominican Republic . 3 Somalia . 9 Summary . 19 Notes . 21 3 POLITICAL IMPACTS ON OPERATIONS . 27 Dominican Republic . 27 Somalia . 35 Summary . 45 Notes . 47 4 INTEROPERABILITY ISSUES . 53 Dominican Republic . 53 Somalia . 59 Intelligence . 63 Summary . 68 Notes . 70 5 CONCLUSION . 75 Notes . 79 Illustrations Figure 1 Map Showing Humanitarian Relief Sectors (Deployment Zones) . 12 2 Weapon Authorization ID Card . 18 3 ROE Pocket Card Issued for Operation Restore Hope . 36 iii Abstract The United States has been involved in peace enforcement operations for many years. In that time we have learned some lessons. Unfortunately, we continue to repeat many of the same mistakes. -

Counterinsurgency in the Iraq Surge

A NEW WAY FORWARD OR THE OLD WAY BACK? COUNTERINSURGENCY IN THE IRAQ SURGE. A thesis presented to the faculty of the Graduate School of Western Carolina University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in US History. By Matthew T. Buchanan Director: Dr. Richard Starnes Associate Professor of History, Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences. Committee Members: Dr. David Dorondo, History, Dr. Alexander Macaulay, History. April, 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Abbreviations . iii Abstract . iv Introduction . 1 Chapter One: Perceptions of the Iraq War: Early Origins of the Surge . 17 Chapter Two: Winning the Iraq Home Front: The Political Strategy of the Surge. 38 Chapter Three: A Change in Approach: The Military Strategy of the Surge . 62 Conclusion . 82 Bibliography . 94 ii ABBREVIATIONS ACU - Army Combat Uniform ALICE - All-purpose Lightweight Individual Carrying Equipment BDU - Battle Dress Uniform BFV - Bradley Fighting Vehicle CENTCOM - Central Command COIN - Counterinsurgency COP - Combat Outpost CPA – Coalition Provisional Authority CROWS- Common Remote Operated Weapon System CRS- Congressional Research Service DBDU - Desert Battle Dress Uniform HMMWV - High Mobility Multi-Purpose Wheeled Vehicle ICAF - Industrial College of the Armed Forces IED - Improvised Explosive Device ISG - Iraq Study Group JSS - Joint Security Station MNC-I - Multi-National-Corps-Iraq MNF- I - Multi-National Force – Iraq Commander MOLLE - Modular Lightweight Load-carrying Equipment MRAP - Mine Resistant Ambush Protected (vehicle) QRF - Quick Reaction Forces RPG - Rocket Propelled Grenade SOI - Sons of Iraq UNICEF - United Nations International Children’s Fund VBIED - Vehicle-Borne Improvised Explosive Device iii ABSTRACT A NEW WAY FORWARD OR THE OLD WAY BACK? COUNTERINSURGENCY IN THE IRAQ SURGE. -

2016 Veterans Day Benefit Gala

2016 Veterans Day Benefit Gala 2016 Gala Guest Speaker General (R) Jack Keane General Jack Keane served 37 years in the Army, rising to the rank of four-star General. Most recently, he held the position of the Vice Chief of Staff of the Army. During his four years in this job as Chief Operating Officer of the United States Army, he managed operations of more than 1.5 million soldiers and civilians in over 120 countries and an annual budget in excess of $110 billion dollars. Throughout his tenure in this position the Army has fought and won wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, while supporting numerous worldwide peace operations, maintaining readiness, and transforming to a faster, more deployable force. As the Vice Chief of Staff, General Keane developed and maintained strong relationships, on behalf of the Army, with Congress, the media, opinion leaders, national security policy makers, and the American people. He testified before Congress on 18 separate occasions on subjects as diverse as the war in Iraq, Military Health Care, the Budget, Environmental Law, Army Readiness and Army transformation. General Keane was a career paratrooper who commanded at every level. He served as the Deputy Commander-in-Chief of the United States Atlantic Command prior to becoming the Army’s Vice Chief of Staff, and was featured in Tom Clancy’s book, AIRBORNE. He is a combat veteran having served as a platoon leader and company commander in Viet Nam. His units deployed to Somalia, Haiti, Bosnia and Kosovo. General Keane graduated from Fordham University business school in 1966 with a Bachelor of Science Degree in Accounting and holds a Masters of Arts Degree in Philosophy from Western Kentucky University. -

Union Calendar No. 709

1 Union Calendar No. 709 114TH CONGRESS " ! REPORT 2nd Session HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 114–898 LEGISLATIVE REVIEW AND OVERSIGHT ACTIVITIES OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS ONE HUNDRED FOURTEENTH CONGRESS A REPORT FILED PURSUANT TO RULE XI OF THE RULES OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES AND SECTION 136 OF THE LEGISLATIVE REORGANIZATION ACT OF 1946 (2 U.S.C. 190d), AS AMENDED BY SECTION 118 OF THE LEGISLATIVE REORGANIZATION ACT OF 1970 (PUBLIC LAW 91–510), AS AMENDED BY PUBLIC LAW 92–136 DECEMBER 30, 2016.—Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 23–170 WASHINGTON : 2016 VerDate Sep 11 2014 03:37 Jan 05, 2017 Jkt 023170 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4012 Sfmt 4012 E:\HR\OC\HR898.XXX HR898 SSpencer on DSK4SPTVN1PROD with REPORTS Congress.#13 U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS COMMITTEE MEMBERSHIP 114TH CONGRESS EDWARD R. ROYCE, California, Chairman (25-19) CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey ELIOT L. ENGEL, New York ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida BRAD SHERMAN, California DANA ROHRABACHER, California GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York STEVE CHABOT, Ohio ALBIO SIRES, New Jersey JOE WILSON, South Carolina GERALD E. CONNOLLY, Virginia MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas THEODORE E. DEUTCH, Florida TED POE, Texas BRIAN HIGGINS, New York MATT SALMON, Arizona KAREN BASS, California DARRELL E. ISSA, California WILLIAM KEATING, Massachusetts TOM MARINO, Pennsylvania DAVID CICILLINE, Rhode Island JEFF DUNCAN, South Carolina ALAN GRAYSON, Florida MO BROOKS, Alabama AMI BERA, California PAUL COOK, California ALAN S. LOWENTHAL, California RANDY K. -

Committee on Foreign Affairs

1 Union Calendar No. 559 113TH CONGRESS " ! REPORT 2nd Session HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 113–728 LEGISLATIVE REVIEW AND OVERSIGHT ACTIVITIES OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS ONE HUNDRED THIRTEENTH CONGRESS A REPORT FILED PURSUANT TO RULE XI OF THE RULES OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES AND SECTION 136 OF THE LEGISLATIVE REORGANIZATION ACT OF 1946 (2 U.S.C. 190d), AS AMENDED BY SECTION 118 OF THE LEGISLATIVE REORGANIZATION ACT OF 1970 (PUBLIC LAW 91–510), AS AMENDED BY PUBLIC LAW 92–136 JANUARY 2, 2015.—Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 49–006 WASHINGTON : 2015 VerDate Sep 11 2014 17:06 Jan 08, 2015 Jkt 049006 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4012 Sfmt 4012 E:\HR\OC\HR728.XXX HR728 mstockstill on DSK4VPTVN1PROD with HEARINGS E:\Seals\Congress.#13 U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS COMMITTEE MEMBERSHIP 113TH CONGRESS EDWARD R. ROYCE, California, Chairman (25–21) CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey ELIOT L. ENGEL, New York ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida ENI F.H. FALEOMAVAEGA, American DANA ROHRABACHER, California Samoa STEVE CHABOT, Ohio BRAD SHERMAN, California JOE WILSON, South Carolina GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas ALBIO SIRES, New Jersey TED POE, Texas GERALD E. CONNOLLY, Virginia MATT SALMON, Arizona THEODORE E. DEUTCH, Florida TOM MARINO, Pennsylvania BRIAN HIGGINS, New York JEFF DUNCAN, South Carolina KAREN BASS, California ADAM KINZINGER, Illinois WILLIAM KEATING, Massachusetts MO BROOKS, Alabama DAVID CICILLINE, Rhode Island TOM COTTON, Arkansas ALAN GRAYSON, Florida PAUL COOK, California JUAN VARGAS, California GEORGE HOLDING, North Carolina BRADLEY S. -

Pbs Quarterly Program Topic Report

July 2005 PBS QUARTERLY PROGRAM TOPIC REPORT ------------------------------------------------------------------------------- QPTR Category: Abortion ------------------------------------------------------------------------------- NOLA Code: NOWD 000130C1 Series Title: NOW Distributor: PBS Release Date: 7/29/2005 7:30:00 PM Length: 30 Format: Interview/Discussion/Review; Magazine; News In a controversial reading of the state's statutory rape law, Kansas Attorney General Phill Kline has pushed to mandate reporting of any sexual activity of people under the age of 16 and subpoenaed medical records of abortion patients. Kline maintains he just wants to enforce the law and protect children, but critics charge that he's attacking a woman's right to an abortion and putting more kids at risk. NOW examines Kline's policies, which have made Kansas ground-zero for the reproductive rights debate in America. The report looks at both sides of the issue and at the implications for the nation. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------- QPTR Category: Agriculture ------------------------------------------------------------------------------- NOLA Code: MLNH 008314C1 Series Title: The NewsHour with Jim Lehrer Distributor: PBS Release Date: 7/20/2005 6:00:00 PM Length: 60 Segment: 00:08:55 Format: Interview/Discussion/Review; News Cultivating Controversy: Betty Ann Bowser provides a report on Minnesota farmers' differing opinions on the Central American Free Trade Agreement. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

Trump's Generals

STRATEGIC STUDIES QUARTERLY - PERSPECTIVE Trump’s Generals: A Natural Experiment in Civil-Military Relations JAMES JOYNER Abstract President Donald Trump’s filling of numerous top policy positions with active and retired officers he called “my generals” generated fears of mili- tarization of foreign policy, loss of civilian control of the military, and politicization of the military—yet also hope that they might restrain his worst impulses. Because the generals were all gone by the halfway mark of his administration, we have a natural experiment that allows us to com- pare a Trump presidency with and without retired generals serving as “adults in the room.” None of the dire predictions turned out to be quite true. While Trump repeatedly flirted with civil- military crises, they were not significantly amplified or deterred by the presence of retired generals in key roles. Further, the pattern continued in the second half of the ad- ministration when “true” civilians filled these billets. Whether longer-term damage was done, however, remains unresolved. ***** he presidency of Donald Trump served as a natural experiment, testing many of the long- debated precepts of the civil-military relations (CMR) literature. His postelection interviewing of Tmore than a half dozen recently retired four- star officers for senior posts in his administration unleashed a torrent of columns pointing to the dangers of further militarization of US foreign policy and damage to the military as a nonpartisan institution. At the same time, many argued that these men were uniquely qualified to rein in Trump’s worst pro- clivities. With Trump’s tenure over, we can begin to evaluate these claims. -

Accounting for Counterinsurgency Doctrines As Solutions to Warfighting Failures in Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan

The Essence of Desperation: Accounting for Counterinsurgency Doctrines as Solutions to Warfighting Failures in Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan William Bryan Riddle Dissertation submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In Planning, Governance & Globalization Gerard Toal Timothy W. Luke Joel Peters Giselle Datz May 4, 2016 Alexandria, Virginia Keywords: Counterinsurgency, Iraq, Vietnam, Afghanistan, Geostrategic Reasoning, Narrative Analysis Copyright 2016 By William Bryan Riddle The Essence of Desperation: Accounting for Counterinsurgency Doctrines as Solutions to Warfighting Failures in Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan William Bryan Riddle ABSTRACT Why does counterinsurgency emerge during periods of warfighting failure and in crisis situations? How is it conceptualized and legitimized? As the second counterinsurgency era for the United States military ends, how such a method of warfare arises, grips the military, policy makers and think tanks provides a tableau for examining how we conceptualize the strategy process and account for geostrategic change. This dissertation takes these puzzles as it object of inquiry and builds on the discursive- argumentative geopolitical reasoning and transactional social construction literatures to explore the ways in which the counterinsurgency narrative captures and stabilizes the policy boundaries of action. It conceptualizes strategy making as a function of defining the problem as one that policy can engage, as the meaning applied to an issue delimits the strategic options available. Once the problem is defined, narratives compete within the national security bureaucracy to overcome the political and strategic fragmentation and produce consensus. A narrative framework is applied to study counterinsurgency strategy during the Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghan wars. -

Reluctant Recruits the US Military and the War on Drugs Peter Zirnite WOLA (Washington Office on Latin America), Washington DC, August 1997

Reluctant Recruits The US Military and the War on Drugs Peter Zirnite WOLA (Washington Office on Latin America), Washington DC, August 1997 CONTENTS • Executive Summary • I. Introduction • I. Calling in the Marines • II. Congress Beats the War Drum • III. Metamorphosis of a Mission • IV. Aiding Latin American Security Forces • Chart 1: US Antinarcotics Assistance, World Distribution • Chart 2: US Antinarcotics Assistance, 1988-1998 • V. Training Latin American Security Forces • Table 1: US Active Duty Personnel in Latin America • VI. Controversy on Capitoll Hill • VII. Detection and Monitoring: The Pentagon's Meat and Potatoes • VIII. Source Country Shift • Table 2: DOD Counternarcotics Spending, FY 1989-1998 • IX. Attacking the "Air Bridge" • X. Domestic Duty? • Table 3: Dept. of Defense Counter-drug Program Operating Tempo • XI. Looking to the Future • XII. Conclusion • A Policy Doomed to Failure • The Negative Consequences • What the Future Holds • Appendix A: The Pentagon's Drug Warriors • Southern Command • Atlantic Command • Pacific Command • Special Operations Command • North American Aerospace Defense Command • Appendix B: US Antinarcotics Assistance 1986-1996 • References Executive Summary Despite the end of the Cold War and recent transitions toward more democratic societies in Latin America, the United States has launched a number of initiatives that strengthen the power of Latin American security forces, increase the resources available to them, and expand their role within society - precisely when struggling civilian elected governments are striving to keep those forces in check. Rather than encourage Latin American militaries to limit their role to the defense of national borders, Washington has provided the training, resources and doctrinal justification for militaries to move into the business of building roads and schools, providing veterinary and child inoculation services, and protecting the environment.