In the Shadow of General Marshall-Old Soldiers in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Political Ideas and Movements That Created the Modern World

harri+b.cov 27/5/03 4:15 pm Page 1 UNDERSTANDINGPOLITICS Understanding RITTEN with the A2 component of the GCE WGovernment and Politics A level in mind, this book is a comprehensive introduction to the political ideas and movements that created the modern world. Underpinned by the work of major thinkers such as Hobbes, Locke, Marx, Mill, Weber and others, the first half of the book looks at core political concepts including the British and European political issues state and sovereignty, the nation, democracy, representation and legitimacy, freedom, equality and rights, obligation and citizenship. The role of ideology in modern politics and society is also discussed. The second half of the book addresses established ideologies such as Conservatism, Liberalism, Socialism, Marxism and Nationalism, before moving on to more recent movements such as Environmentalism and Ecologism, Fascism, and Feminism. The subject is covered in a clear, accessible style, including Understanding a number of student-friendly features, such as chapter summaries, key points to consider, definitions and tips for further sources of information. There is a definite need for a text of this kind. It will be invaluable for students of Government and Politics on introductory courses, whether they be A level candidates or undergraduates. political ideas KEVIN HARRISON IS A LECTURER IN POLITICS AND HISTORY AT MANCHESTER COLLEGE OF ARTS AND TECHNOLOGY. HE IS ALSO AN ASSOCIATE McNAUGHTON LECTURER IN SOCIAL SCIENCES WITH THE OPEN UNIVERSITY. HE HAS WRITTEN ARTICLES ON POLITICS AND HISTORY AND IS JOINT AUTHOR, WITH TONY BOYD, OF THE BRITISH CONSTITUTION: EVOLUTION OR REVOLUTION? and TONY BOYD WAS FORMERLY HEAD OF GENERAL STUDIES AT XAVERIAN VI FORM COLLEGE, MANCHESTER, WHERE HE TAUGHT POLITICS AND HISTORY. -

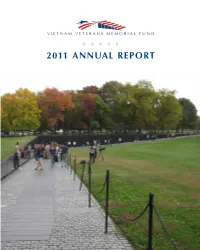

2011 Annual Report Dear Friends

2011 ANNUAL REPORT DEar FRIENDS: When engaged in the mission of the Vietnam Veterans The Call for Photos is a Memorial Fund, there is a word that I’m particularly fond of. primary focus at each of The That word is: momentum. For those connected with VVMF, Wall that Heals tour stops. 2011 was all about building momentum. In the course of VVMF’s 2011 tour season hit OUR MISSION this one year, the programs we dedicated ourselves to have over 30 cities, maximizing gathered more and more steam, and resulted in forward awareness and fundraising for To preserve the legacy of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, motion that is carrying us closer to the goals contained in our the Education Center. mission statement. to promote healing and to educate about the impact of In 2011, we produced and It is this momentum that will take us into our 30th released a new Build the Center Warren Kahle the Vietnam War Anniversary year, and far beyond. The energy and drive public service announcement 2011 ANNUAL REPORT created in 2011 will propel us as we go about the challenge campaign. The beautifully filmed PSAs included notable of making the dream of the Education Center at The Wall a Americans sending the powerful message of, “Get involved reality. In it, we will honor those who fell in Vietnam, those and help them build it.” who fought and returned, as well as the friends and families of all who served. To highlight the grassroots activities and fundraising efforts, we dramatically increased and improved VVMF’s online Since 1982, The Wall has stood as a solemn tribute to those presence. -

The Moorer Commission

The Moorer Commission 1 Findings of the Independent Commission of Inquiry into the Israeli Attack on USS Liberty, the Recall of Military Rescue Support Aircraft while the Ship was Under Attack, and the Subsequent Cover - up by the United States Government October 22, 2003 Admiral Thomas H. Moorer, U.S. Navy (deceased) Former Chairman, Joint Chiefs of Staff General Raymond G. Davis, U.S. Marine Corps (deceased) (MOH)*, Former Assistant Commandant of the Marine Corps Rear Admiral Merlin Staring, U.S. Navy (deceased) Former Judge Advocate of the Navy (73 - 75) Ambassador James Akins (deceased) Former U.S. Ambassador to Saudi Arabia (73 - 76) We, the undersigned having undertaken an independent investigation of Israel’s attack on USS Liberty , including eyewit ness testimony from surviving crewmembers, a review of naval and other official records, an examination of official statements by the Israeli and American governments, a study of the conclusions of all previous official inquiries, and a consideration of im portant new evidence and recent statements from individuals having direct knowledge of the attack or the cover up, hereby find the following:** 1. That on June 8, 1967, after eight hours of aerial surveillance, Israel launched a two - hour air and naval attack against USS Liberty, the world’s most sophisticated intelligence ship, inflicting 34 dead, and 173 wounded American servicemen (a casualty rate of 70%, in a crew of 294).; 2 2. That the Israeli air attack lasted approximately 25 minutes, during which time un marked Israeli aircraft dropped napalm canisters on USS Liberty’s bridge, and fired 30mm cannons and rockets into our ship, causing 821 holes, more than 100 of which were rocket - size; survivors estimate 30 or more sorties were flown over the ship by minimu m of 12 attacking Israeli planes which were jamming all 5 American emergency radio channels; 3. -

The Civilian Impact of Drone Strikes

THE CIVILIAN IMPACT OF DRONES: UNEXAMINED COSTS, UNANSWERED QUESTIONS Acknowledgements This report is the product of a collaboration between the Human Rights Clinic at Columbia Law School and the Center for Civilians in Conflict. At the Columbia Human Rights Clinic, research and authorship includes: Naureen Shah, Acting Director of the Human Rights Clinic and Associate Director of the Counterterrorism and Human Rights Project, Human Rights Institute at Columbia Law School, Rashmi Chopra, J.D. ‘13, Janine Morna, J.D. ‘12, Chantal Grut, L.L.M. ‘12, Emily Howie, L.L.M. ‘12, Daniel Mule, J.D. ‘13, Zoe Hutchinson, L.L.M. ‘12, Max Abbott, J.D. ‘12. Sarah Holewinski, Executive Director of Center for Civilians in Conflict, led staff from the Center in conceptualization of the report, and additional research and writing, including with Golzar Kheiltash, Erin Osterhaus and Lara Berlin. The report was designed by Marla Keenan of Center for Civilians in Conflict. Liz Lucas of Center for Civilians in Conflict led media outreach with Greta Moseson, pro- gram coordinator at the Human Rights Institute at Columbia Law School. The Columbia Human Rights Clinic and the Columbia Human Rights Institute are grateful to the Open Society Foundations and Bullitt Foundation for their financial support of the Institute’s Counterterrorism and Human Rights Project, and to Columbia Law School for its ongoing support. Copyright © 2012 Center for Civilians in Conflict (formerly CIVIC) and Human Rights Clinic at Columbia Law School All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America. Copies of this report are available for download at: www.civiliansinconflict.org Cover: Shakeel Khan lost his home and members of his family to a drone missile in 2010. -

1 BARACK OBAMA, ABRAHAM LINCOLN, and JOHN DEWEY In

File: Schulten web preprint Created on: 1/29/2009 9:52:00 AM Last Printed: 1/31/2009 2:13:00 PM BARACK OBAMA, ABRAHAM LINCOLN, AND JOHN DEWEY SUSAN SCHULTEN In the last few months, there has been a spate of comparisons be- tween Obama and some of our most influential former presidents. Just days after the election, Congress announced the theme of the inaugura- tion as “A New Birth of Freedom,” while reporters and commentators speculate about “A New New Deal” or “Lincoln 2.0.”1 Many of these comparisons are situational: Obama is a relatively inexperienced lawyer- turned-politician who will inherit two wars and an economic crisis un- equalled since the Great Depression.2 The backlash has been equally vocal. Many consider these com- parisons both premature and presumptuous, evidence that the media is sympathetic toward an Obama Administration or that the President-elect has himself orchestrated these connections.3 Indeed, Obama frequently invoked Lincoln as both a model for and an influence over his own can- didacy, which he launched on the steps of the Old State Capitol in Springfield, Illinois. He introduced Vice-President Joe Biden in the same spot, where the latter also referenced the memory of Lincoln.4 Cer- tainly it makes sense for Obama to exploit Lincoln’s legacy, for no other figure in American history continues to command such admiration, the occasional neo-Confederate or other detractor notwithstanding.5 To posi- tion Obama in front of the State House is surely meant to place him as a kind of an heir to Lincoln. -

Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference by Fletcher Schoen and Christopher J

STRATEGIC PERSPECTIVES 11 Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference by Fletcher Schoen and Christopher J. Lamb Center for Strategic Research Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University The Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS) is National Defense University’s (NDU’s) dedicated research arm. INSS includes the Center for Strategic Research, Center for Complex Operations, Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs, Center for Technology and National Security Policy, Center for Transatlantic Security Studies, and Conflict Records Research Center. The military and civilian analysts and staff who comprise INSS and its subcomponents execute their mission by conducting research and analysis, publishing, and participating in conferences, policy support, and outreach. The mission of INSS is to conduct strategic studies for the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Unified Combatant Commands in support of the academic programs at NDU and to perform outreach to other U.S. Government agencies and the broader national security community. Cover: Kathleen Bailey presents evidence of forgeries to the press corps. Credit: The Washington Times Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference By Fletcher Schoen and Christopher J. Lamb Institute for National Strategic Studies Strategic Perspectives, No. 11 Series Editor: Nicholas Rostow National Defense University Press Washington, D.C. June 2012 Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Defense Department or any other agency of the Federal Government. -

Thank You. I Want to Thank Michael for His Opening Remarks, and Michael and Steve for Hosting Me Here Today

“The United States - Africa Partnership: The Last Four Years and Beyond” Assistant Secretary Carson The Wilson Center, Washington DC As Prepared Version Thank you. I want to thank Michael for his opening remarks, and Michael and Steve for hosting me here today. I also want to thank all of the distinguished guests in the audience, including members of the diplomatic corps and colleagues from the think tank community. It is an honor to speak to such a distinguished group of leaders who, like me, are so committed to Africa. Let me also thank my wife, Anne. She and I have spent most of our lives working on Africa, and nothing that I have accomplished would have been possible without her advice, partnership, and support. My interest in Africa started in the mid-1960s when I served as a Peace Corps volunteer in Tanzania. The 1960s was a time of great promise for Africa. As newly independent nations struggled to face what many regarded as the insurmountable challenges of democracy, development, and economic growth, newly independent people looked forward to embracing an era of opportunity and optimism. This promise also inspired me to enter the Foreign Service. After more than forty years of experience in Africa, three Ambassadorships, and now four years as Assistant Secretary for African Affairs, I have experienced first- hand Africa’s triumphs, tragedies, and progress. And despite Africa's -2- uneven progress, I remain deeply optimistic about Africa’s future. This optimism is grounded in expanding democracy, improved security, rapid economic growth, and greater opportunities for Africa’s people. -

Directors of Central Intelligence As Leaders of the U.S

All statements of fact, opinion, or analysis expressed in this book are those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Central Intel- ligence Agency or any other US government entity, past or present. Nothing in the contents should be construed as asserting or implying US government endorsement of the authors’ factual statements and interpretations. The Center for the Study of Intelligence The Center for the Study of Intelligence (CSI) was founded in 1974 in response to Director of Central Intelligence James Schlesinger’s desire to create within CIA an organization that could “think through the functions of intelligence and bring the best intellects available to bear on intelli- gence problems.” The Center, comprising professional historians and experienced practitioners, attempts to document lessons learned from past operations, explore the needs and expectations of intelligence consumers, and stimulate serious debate on current and future intelligence challenges. To support these activities, CSI publishes Studies in Intelligence and books and monographs addressing historical, operational, doctrinal, and theoretical aspects of the intelligence profession. It also administers the CIA Museum and maintains the Agency’s Historical Intelligence Collection. Comments and questions may be addressed to: Center for the Study of Intelligence Central Intelligence Agency Washington, DC 20505 Printed copies of this book are available to requesters outside the US government from: Government Printing Office (GPO) Superintendent of Documents P.O. Box 391954 Pittsburgh, PA 15250-7954 Phone: (202) 512-1800 E-mail: [email protected] ISBN: 1-929667-14-0 The covers: The portraits on the front and back covers are of the 19 directors of central intelligence, beginning with the first, RAdm. -

Future of Global Competition and Conflict Vitta Q4 Report Final

A Virtual Think Tank (ViTTa®) Report September 2019 Russia’s Sentimental Revisionist Approach to Competition and Conflict Deeper Analyses Clarifying Insights Better Decisions NSIteam.com Produced in support of the Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA) Office (Joint Staff, J39) Russia’s Sentimental Revisionist Approach to Competition and Conflict Author George Popp Editors Sarah Canna, George Popp, and Dr. John A. Stevenson Please direct inquiries to George Popp at [email protected] What is ViTTa? NSI’s Virtual Think Tank (ViTTa) provides rapid response to critical information needs by pulsing a global network of subject matter experts (SMEs) to generate a wide range of expert insight. For the Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA) Future of Global Competition and Conflict project, ViTTa was used to address 12 key questions provided by the project’s Joint Staff sponsors. The ViTTa team received written response submissions from 65 subject matter experts from academia, government, military, and industry. This report consists of: 1. A summary overview of the expert contributor response to the ViTTa question of focus. 2. The full corpus of expert contributor responses received for the ViTTa question of focus. 3. Biographies of expert contributors. _________________________________ Cover image: https://www.prosperity.com/application/files/thumbnails/small/3114/7802/0180/Russia_header.jpg RESEARCH ▪ INNOVATIONNSI ▪ EXCELLENCE II Russia’s Sentimental Revisionist Approach to Competition and Conflict Table of Contents What is ViTTa? ................................................................................................................................................................ -

Sudan and South Sudan: Current Issues for Congress and U.S. Policy

Sudan and South Sudan: Current Issues for Congress and U.S. Policy -name redacted- Specialist in African Affairs October 5, 2012 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov R42774 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Sudan and South Sudan: Current Issues for Congress and U.S. Policy Summary Congress has played an active role in U.S. policy toward Sudan for more than three decades. Efforts to support an end to the country’s myriad conflicts and human rights abuses have dominated the agenda, as have counterterrorism concerns. When unified (1956-2011), Sudan was Africa’s largest nation, bordering nine countries and stretching from the northern borders of Kenya and Uganda to the southern borders of Egypt and Libya. Strategically located along the Nile River and the Red Sea, Sudan was historically described as a crossroads between the Arab world and Africa. Domestic and international efforts to unite its ethnically, racially, religiously, and culturally diverse population under a common national identity fell short, however. In 2011, after decades of civil war and a 6.5 year transitional period, Sudan split in two. Mistrust between the two Sudans—Sudan and South Sudan—lingers, and unresolved disputes and related security issues still threaten to pull the two countries back to war. The north-south split did not resolve other simmering conflicts, notably in Darfur, Blue Nile, and Southern Kordofan. Roughly 2.5 million people remain displaced as a result of these conflicts. Like the broader sub-region, the Sudans are susceptible to drought and food insecurity, despite significant agricultural potential in some areas. -

Development of a Military Command System: Technological and Social Influences

University of North Georgia Nighthawks Open Institutional Repository Honors Theses Honors Program Spring 4-13-2021 Development of a Military Command System: Technological and Social Influences Holden James Armstrong [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.northgeorgia.edu/honors_theses Part of the American Politics Commons, Defense and Security Studies Commons, Leadership Studies Commons, Military History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Armstrong, Holden James, "Development of a Military Command System: Technological and Social Influences" (2021). Honors Theses. 65. https://digitalcommons.northgeorgia.edu/honors_theses/65 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at Nighthawks Open Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Nighthawks Open Institutional Repository. Development of a Military Command System: Technological and Social Influences A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the University of North Georgia In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts in Strategic and Security Studies With Honors Holden Armstrong Spring 2021 Acknowledgments Firstly, I would like to thank Dr. Johnathan Beall for patiently working with me over these last two years on this project. I am sure that at times it was trying for you as well. Without Dr. Beall’s patient guidance, I would never have been able to turn my original fledgling research topic of an archetypical general into a defendable thesis on a concert research question. My interest in this field was sparked during Dr. Beall’s courses, practically his History of Military Thought in the Spring of 2019. -

The Abu Ghraib Convictions: a Miscarriage of Justice

Buffalo Public Interest Law Journal Volume 32 Article 4 9-1-2013 The Abu Ghraib Convictions: A Miscarriage of Justice Robert Bejesky Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/bpilj Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, and the Military, War, and Peace Commons Recommended Citation Robert Bejesky, The Abu Ghraib Convictions: A Miscarriage of Justice, 32 Buff. Envtl. L.J. 103 (2013). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/bpilj/vol32/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Buffalo Public Interest Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ABU GHRAIB CONVICTIONS: A MISCARRIAGE OF JUSTICE ROBERT BEJESKYt I. INTRODUCTION ..................... ..... 104 II. IRAQI DETENTIONS ...............................107 A. Dragnet Detentions During the Invasion and Occupation of Iraq.........................107 B. Legal Authority to Detain .............. ..... 111 C. The Abuse at Abu Ghraib .................... 116 D. Chain of Command at Abu Ghraib ..... ........ 119 III. BASIS FOR CRIMINAL CULPABILITY ..... ..... 138 A. Chain of Command ....................... 138 B. Systemic Influences ....................... 140 C. Reduced Rights of Military Personnel and Obedience to Authority ................ ..... 143 D. Interrogator Directives ................ ....