On the Western Front, 1915-18

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Battle of Moreuil Wood

The Battle of Moreuil Wood By Captain J.R. Grodzinski, LdSH(RC) On 9 October 1918, Lord Strathcona's Horse (Royal Canadians) fought their last battle of the First World War. Having been in reserve since August 1918, the Strathconas and the other two cavalry Regiments of the Canadian Cavalry Brigade were rushed to the front to exploit a penetration made in the German defences. In just one day, the Brigade advanced ten kilometers on a five kilometer front, capturing four hundred prisoners and numerous weapons. A spirited charge by the Strathconas over 1500 yards of open ground helped clear the village of Clary, southeast of Cambrai. This battle, which commenced at 0930 hours and finished by 1100 hours, assisted in clearing the neighboring Bois de Gattigny and the Bois du Mont-Auxvilles, Where two hundred prisoners were taken and a howitzer and forty machine guns captured. Several squadron-sized charges were made as the Regiments raced forward. The battle moved faster than senior commanders could react to and issue new instructions. This was mobile warfare, the type the cavalry longed for throughout the war. To those in the Canadian Cavalry Brigade and particularly the Strathconas this final action, known as the Battle of Le Cateau, probably brought recollection of a similar, yet more intense fight the previous spring: The Battle of Moreuil Wood on 30 March 1918. January 1918. The war was in its fourth year. Initially a mobile conflict, it quickly became a static slugging match. Intense fighting gave little advantage to either side while the numbers of casualties increased. -

The Battle of Cambrai

THE BATTLE OF CAMBRAI GERMAN OCCUPATION REPORTS / MAPS / PICTURES THE BATTLE OF CAMBRAI Although its noise and fury could be heard from the town itself, in reality the Battle of Cambrai took place across the south of the Cambrésis. The confrontations which happened between November 20 th and December 7 th , 1917, setting They are assuring us that the 476 British armoured vehicles against the German Army, town of Cambrai was on the point protected by the Hindenburg line, were imprinted on the spirits of those who lived there, and destroyed whole villages. of being liberated yesterday, that the English got as far as Noyelles , Today the apocalyptic landscape created by the battle has that the Germans were going to given way to cultivated fields and rebuilt villages, but the deeply moving memories remain: photographs, personal flee without worrying about the diaries, blockhouses, cemeteries... population, but that the attack The ‘Cambrai : Town of Art and History’ service and the stopped suddenly and that our Cambresis Tourist Office invite you to discover this land, allies withdrew by two miles this so physically marked by the terrible conflicts of the last morning. Powerful reinforcements Fortified position - Hindenburg line century, many remnants of which are housed at the Cambrai German defensive line Tank 1917 museum. were sent to the Germans and ENGLISH POSITIONS we are still held in the chains of Cambresis Tourist Office British position on november 20 th 1917 48 rue de Noyon - 59400 Cambrai our slavery. Place du Général de Gaulle - 59540 Caudry Mrs Mallez, 21 November 1917 Place du Général de Gaulle - 59360 Le Cateau-Cambrésis British farthest position during 03 27 78 36 15 • [email protected] the Battle of Cambrai www.tourisme-cambresis.fr Only a few large, isolated shells fell now, one of which exploded immediately in front th of us, a welcome from hell, filling all the British position on december 7 1917 canal bed in a heavy and sombre smoke. -

Memorial at Contalmaison, France

Item no Report no CPC/ I b )03-ClVke *€DINBVRGH + THE CITY OF EDINBURGH COUNCIL Hearts Great War Memorial Fund - Memorial at Contalmaison, France The City of Edinburgh Council 29 April 2004 Purpose of report 1 This report provides information on the work being undertaken by the Hearts Great War Memorial Fund towards the establishment of a memorial at Contalmaison, France, and seeks approval of a financial contribution from the Council. Main report 2 The Hearts Great War Memorial Committee aims to establish and maintain a physical commemoration in Contalmaison, France, in November this year, of the participation of the Edinburgh l!jthand 16th Battalions of the Royal Scots at the Battle of the Somme. 3 Members of the Regiment had planned the memorial as far back as 1919 but, for a variety of reasons, this was not progressed and the scheme foundered because of a lack of funds. 4 There is currently no formal civic acknowledgement of the two City of Edinburgh Battalions, Hearts Great War Memorial Committee has, therefore, revived the plan to establish, within sight of the graves of those who died in the Battle of the Somme, a memorial to commemorate the sacrifice made by Sir George McCrae's Battalion and the specific role of the players and members of the Heart of Midlothian Football Club and others from Edinburgh and the su rround i ng a reas. 5 It is hoped that the memorial cairn will be erected in the town of Contalmaison, to where the 16thRoyal Scots advanced on the first day of the battle of the 1 Somme in 1916. -

The Western Front the First World War Battlefield Guide: World War Battlefield First the the Westernthe Front

Ed 2 June 2015 2 June Ed The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 1 The Western Front The First Battlefield War World Guide: The Western Front The Western Creative Media Design ADR003970 Edition 2 June 2015 The Somme Battlefield: Newfoundland Memorial Park at Beaumont Hamel Mike St. Maur Sheil/FieldsofBattle1418.org The Somme Battlefield: Lochnagar Crater. It was blown at 0728 hours on 1 July 1916. Mike St. Maur Sheil/FieldsofBattle1418.org The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 1 The Western Front 2nd Edition June 2015 ii | THE WESTERN FRONT OF THE FIRST WORLD WAR ISBN: 978-1-874346-45-6 First published in August 2014 by Creative Media Design, Army Headquarters, Andover. Printed by Earle & Ludlow through Williams Lea Ltd, Norwich. Revised and expanded second edition published in June 2015. Text Copyright © Mungo Melvin, Editor, and the Authors listed in the List of Contributors, 2014 & 2015. Sketch Maps Crown Copyright © UK MOD, 2014 & 2015. Images Copyright © Imperial War Museum (IWM), National Army Museum (NAM), Mike St. Maur Sheil/Fields of Battle 14-18, Barbara Taylor and others so captioned. No part of this publication, except for short quotations, may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the permission of the Editor and SO1 Commemoration, Army Headquarters, IDL 26, Blenheim Building, Marlborough Lines, Andover, Hampshire, SP11 8HJ. The First World War sketch maps have been produced by the Defence Geographic Centre (DGC), Joint Force Intelligence Group (JFIG), Ministry of Defence, Elmwood Avenue, Feltham, Middlesex, TW13 7AH. United Kingdom. -

Tour Sheets Final04-05

Great War Battlefields Study Tour Briefing Notes & Activity Sheets Students Name briefing notes one Introduction The First World War or Great War was a truly terrible conflict. Ignored for many years by schools, the advent of the National Curriculum and the GCSE system reignited interest in the period. Now, thousands of pupils across the United Kingdom study the 1914-18 era and many pupils visit the battlefield sites in Belgium and France. Redevelopment and urban spread are slowly covering up these historic sites. The Mons battlefields disappeared many years ago, very little remains on the Ypres Salient and now even the Somme sites are under the threat of redevelopment. In 25 years time it is difficult to predict how much of what you see over the next few days will remain. The consequences of the Great War are still being felt today, in particular in such trouble spots as the Middle East, Northern Ireland and Bosnia.Many commentators in 1919 believed that the so-called war to end all wars was nothing of the sort and would inevitably lead to another conflict. So it did, in 1939. You will see the impact the war had on a local and personal level. Communities such as Grimsby, Hull, Accrington, Barnsley and Bradford felt the impact of war particularly sharply as their Pals or Chums Battalions were cut to pieces in minutes during the Battle of the Somme. We will be focusing on the impact on an even smaller community, our school. We will do this not so as to glorify war or the part oldmillhillians played in it but so as to use these men’s experiences to connect with events on the Western Front. -

The British Empire on the Western Front: a Transnational Study of the 62Nd West Riding Division and the Canadian 4Th Division

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2013-09-24 The British Empire on the Western Front: A Transnational Study of the 62nd West Riding Division and the Canadian 4th Division Jackson, Geoffrey Jackson, G. (2013). The British Empire on the Western Front: A Transnational Study of the 62nd West Riding Division and the Canadian 4th Division (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/28020 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/1036 doctoral thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY The British Empire on the Western Front: A Transnational Study of the 62nd West Riding Division and the Canadian 4th Division By Geoffrey Jackson A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY CENTRE FOR MILITARY AND STRATEGIC STUDIES CALGARY, ALBERTA SEPTEMBER 2013 © Geoffrey Jackson 2013 Abstract This dissertation is a detailed transnational comparative analysis focusing on two military units representing notably different societies, though ones steeped in similar military and cultural traditions. This project compared and contrasted training, leadership and battlefield performance of a division from each of the British and Canadian Expeditionary Forces during the First World War. -

The Evolution of British Tactical and Operational Tank Doctrine and Training in the First World War

The evolution of British tactical and operational tank doctrine and training in the First World War PHILIP RICHARD VENTHAM TD BA (Hons.) MA. Thesis submitted for the award of the degree of Master of Philosophy by the University of Wolverhampton October 2016 ©Copyright P R Ventham 1 ABSTRACT Tanks were first used in action in September 1916. There had been no previous combat experience on which to base tactical and operational doctrine for the employment of this novel weapon of war. Training of crews and commanders was hampered by lack of vehicles and weapons. Time was short in which to train novice crews. Training facilities were limited. Despite mechanical limitations of the early machines and their vulnerability to adverse ground conditions, the tanks achieved moderate success in their initial actions. Advocates of the tanks, such as Fuller and Elles, worked hard to convince the sceptical of the value of the tank. Two years later, tanks had gained the support of most senior commanders. Doctrine, based on practical combat experience, had evolved both within the Tank Corps and at GHQ and higher command. Despite dramatic improvements in the design, functionality and reliability of the later marks of heavy and medium tanks, they still remained slow and vulnerable to ground conditions and enemy counter-measures. Competing demands for materiel meant there were never enough tanks to replace casualties and meet the demands of formation commanders. This thesis will argue that the somewhat patchy performance of the armoured vehicles in the final months of the war was less a product of poor doctrinal guidance and inadequate training than of an insufficiency of tanks and the difficulties of providing enough tanks in the right locations at the right time to meet the requirements of the manoeuvre battles of the ‘Hundred Days’. -

6/11/2021 Page 1 Powered by Resident Population and Its

9/28/2021 Maps, analysis and statistics about the resident population Demographic balance, population and familiy trends, age classes and average age, civil status and foreigners Skip Navigation Links FRANCIA / HAUTS DE FRANCE / Province of PAS DE CALAIS / Trescault Powered by Page 1 L'azienda Contatti Login Urbistat on Linkedin Adminstat logo DEMOGRAPHY ECONOMY RANKINGS SEARCH FRANCIA Municipalities Powered by Page 2 Ablain-Saint- Stroll up beside >> L'azienda Contatti Login Urbistat on Linkedin Nazaire Esquerdes Adminstat logo DEMOGRAPHY ECONOMY RANKINGS SEARCH Ablainzevelle FRANCIAEssars Acheville Estevelles Achicourt Estrée Achiet-le-Grand Estrée-Blanche Achiet-le-Petit Estrée-Cauchy Acq Estrée-Wamin Acquin- Estréelles Westbécourt Étaing Adinfer Étaples Affringues Éterpigny Agnez- Étrun lès-Duisans Évin-Malmaison Agnières Famechon Agny Fampoux Aire-sur-la-Lys Farbus Airon- Fauquembergues Notre-Dame Favreuil Airon- Saint-Vaast Febvin-Palfart Aix-en-Ergny Ferfay Aix-en-Issart Ferques Aix-Noulette Festubert Alembon Feuchy Alette Ficheux Alincthun Fiefs Allouagne Fiennes Alquines Fillièvres Ambleteuse Fléchin Ambricourt Flers Ambrines Fleurbaix Ames Fleury Amettes Floringhem Amplier Foncquevillers Andres Fontaine- l'Étalon Angres Fontaine- Annay lès-Boulans Annequin Fontaine- Annezin lès-Croisilles Anvin Fontaine- Anzin- lès-Hermans Saint-Aubin Fortel-en-Artois Powered by Page 3 Ardres Fosseux L'azienda Contatti Login Urbistat on Linkedin Provinces Arleux- Foufflin- Adminstat logo en-Gohelle Ricametz DEMOGRAPHY ECONOMY RANKINGS SEARCH -

100 % Ressourcé N° 1 -2019 PDF 6.18 Mo Télécharger

100%RESSOURCĒ MAGAZINE ANNUEL DU SYNDICAT MIXTE ARTOIS VALORISATION 2019 56 En infographie LE CALENDRIER DES COLLECTES 2019 54 Il était une fois… LA FAMILLE (PRESQUE) ZÉRO DÉCHET QUI VIVAIT DANS UNE MAISON RECYCLÉE 24 Solutions BIENTÔT 100% DES DÉCHETS VALORISÉS AVEC LA MISE EN SERVICE DU SÉLECTROM TERRITOIRES SOLUTIONS INITIATIVES Intercommunalités en Le SMAV moteur de Citoyens à la conquête transition écologique l'économie circulaire de la planète verte 17 23 39 • COMMUNAUTÉ URBAINE D’ARRAS • COMMUNAUTÉ DE COMMUNES DU SUD-ARTOIS • COMMUNAUTÉ DE COMMUNES DES CAMPAGNES DE L’ARTOIS : 3 intercommunalités AU SEIN DU SMAV Magnicourt-en-Comté Frévillers Béthonsart Centre de valorisation Chelers Cambligneul énergétique par DENSITÉ DE POPULATION Bailleul-aux- Mingoval Villers- incinération Cornailles Villers- Châtel Camblain-l’Abbé de 0 à 49 hab./km2 Brûlin (Saint-Saulve) de 50 à 99 hab./km2 Tincques Savy- Agnières Farbus Willerval Berlette Frévin- Neuville- 2 Saint-Vaast de 100 à 199 hab./km Berles- Capelle Mont- Thélus 2 Monchel Aubigny-D Capelle- Saint-Éloi de 200 à 399 hab./km en-Artois Fermont Acq D de 400 à 599 hab./km2 Penin Écurie Bailleul-Sire- Tilloy-lès- Haute- D Roclincourt Berthoult 2 Maizières Hermaville Avesnes Marœuil Gavrelle de 600 à 999 hab./km Anzin- Saint- Villers- Izel-lès- Hermaville Laurent- 1 000 hab./km2 et plus Sir-Simon Hameau Agnez-lès- Étrun St-Aubin Ste- Duisans Blangy Magnicourt- Lattre- Habarcq Catherine Fampoux sur-Canche Ambrines Saint- St- Athies Quentin Nicolas Communauté de Communes Givenchy- Duisans D Houvin- -

The Canadian Militia in the Interwar Years, 1919-39

THE POLICY OF NEGLECT: THE CANADIAN MILITIA IN THE INTERWAR YEARS, 1919-39 ___________________________________________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board ___________________________________________________________ in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY __________________________________________________________ by Britton Wade MacDonald January, 2009 iii © Copyright 2008 by Britton W. MacDonald iv ABSTRACT The Policy of Neglect: The Canadian Militia in the Interwar Years, 1919-1939 Britton W. MacDonald Doctor of Philosophy Temple University, 2008 Dr. Gregory J. W. Urwin The Canadian Militia, since its beginning, has been underfunded and under-supported by the government, no matter which political party was in power. This trend continued throughout the interwar years of 1919 to 1939. During these years, the Militia’s members had to improvise a great deal of the time in their efforts to attain military effectiveness. This included much of their training, which they often funded with their own pay. They created their own training apparatuses, such as mock tanks, so that their preparations had a hint of realism. Officers designed interesting and unique exercises to challenge their personnel. All these actions helped create esprit de corps in the Militia, particularly the half composed of citizen soldiers, the Non- Permanent Active Militia. The regulars, the Permanent Active Militia (or Permanent Force), also relied on their own efforts to improve themselves as soldiers. They found intellectual nourishment in an excellent service journal, the Canadian Defence Quarterly, and British schools. The Militia learned to endure in these years because of all the trials its members faced. The interwar years are important for their impact on how the Canadian Army (as it was known after 1940) would fight the Second World War. -

Memorials to Scots Who Fought on the Western Front in World War One

Memorials to Scots who fought on the Western Front in World War One Across Flanders and France there are many memorials to those of all nations Finding the memorials who fell in World War One. This map is intended to assist in identifying those for The map on the next page shows the general location on the the Scots who made the ultimate sacrifice during the conflict. Western Front of the memorials for Scottish regiments or Before we move to France and Flanders, let’s take a look at Scotland’s National battalions. If the memorial is in a Commonwealth War Graves War Memorial. Built following World War One, the memorial stands at the Commission Cemetery then that website will give you directions. highest point in Edinburgh Castle. Designed by Sir Robert Lorimer and funded by donations, the memorial is an iconic building. Inside are recorded the names of all Scots who fell in World War One and all subsequent For other memorials and for road maps you could use an conflicts while serving in the armed forces of the United online map such as ViaMichelin. Kingdom and the Empire, in the Merchant Navy, women’s and nursing services, as well as civilians killed at home and overseas. What the memorials commemorate The descriptions of the memorials in this list are designed to give you a brief outline of what and who is being commemorated. By using the QR code provided you will be taken to a website that will tell you a bit more. Don’t forget there are likely to be many more websites in various formats that will provide similar information and by doing a simple search you may find one that is more suitable for your interest. -

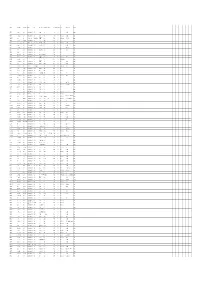

Wfdwa-Rsl-181112

SURNAME FIRST NAMES RANK at Death REGIMENT UNIT WHERE BORN BORN STATE HONOURS DOD (DD MMM) YOD (YYYY) COD PLACE OF DEATH COUNTRY A'HEARN Edward John Private Australian Infantry, AIF 44th Bn Wilcannia NSW 4 Oct 1917 KIA In the field Belgium AARONS John Fullarton Private Australian Infantry, AIF 16th Bn Hillston NSW 11 Jul 1917 DOW (Wounds) In the field France Manchester, ABBERTON Edmund Sapper Australian Engineers 3rd Div Signal Coy England 6 Nov 1918 DOI (Illness, acute) 1 AAH, Harefield England Lancashire ABBOTT Charles Edgar Lance Corporal Australian Infantry, AIF 11th Bn Avoca Victoria 30 May 1916 KIA - France ABBOTT Charles Henry Sapper Australian Engineers 3rd Tunnelling Coy Maryborough Victoria 26 May 1917 DOW (Wounds) In the field France ABBOTT Henry Edgar Private Australian Army Medical Corp10th AFA Burra or Hoylton SA 12 Oct 1917 KIA In the field Belgium ABBOTT Oliver Oswald Private Australian Infantry, AIF 11th Bn Hoyleton SA 22 Aug 1916 KIA Mouquet Farm France ABBOTT Robert Private Australian Infantry, AIF 11th Bn Malton, Yorkshire England 25 Jul 1916 KIA France France ABOLIN Martin Private Australian Infantry, AIF 44th Bn Riga Russia 10 Jun 1917 KIA - Belgium ABRAHAM William Strong Private Australian Infantry, AIF 11th Bn Mepunga, WarnnamboVictoria 25 Jul 1916 KIA - France Southport, ABRAM Richard Private Australian Infantry, AIF 28th Bn England 29 Jul 1916 Declared KIA Pozieres France Lancashire ACKLAND George Henry Private Royal Warwickshireshire Reg14th Bn N/A N/A 8 Feb 1919 DOI (Illness, acute) - England Manchester, ACKROYD