The Theory of the Pathetic Fallacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

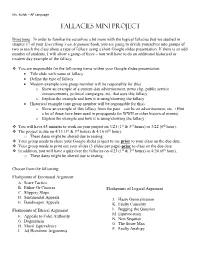

Fallacies Mini Project

Ms. Kizlyk – AP Language Fallacies Mini Project Directions: In order to familiarize ourselves a bit more with the logical fallacies that we studied in chapter 17 of your Everything’s an Argument book, you are going to divide yourselves into groups of two to teach the class about a type of fallacy using a short Google slides presentation. If there is an odd number of students, I will allow a group of three – you will have to do an additional historical or modern day example of the fallacy. You are responsible for the following items within your Google slides presentation: Title slide with name of fallacy Define the type of fallacy Modern example (one group member will be responsible for this) o Show an example of a current-day advertisement, news clip, public service announcements, political campaigns, etc. that uses this fallacy o Explain the example and how it is using/showing the fallacy Historical example (one group member will be responsible for this) o Show an example of this fallacy from the past – can be an advertisement, etc. (Hint – a lot of these have been used in propaganda for WWII or other historical events). o Explain the example and how it is using/showing the fallacy You will have 45 minutes to work on your project on 3/21 (1st & 3rd hours) or 3/22 (6th hour). The project is due on 4/13 (1st & 3rd hours) & 4/16 (6th hour). o These dates might be altered due to testing. Your group needs to share your Google slides project to me prior to your class on the due date. -

Annual Review 2009 Sharks (Costa Rica), Pretoma

Annual Review 2009 Sharks (Costa Rica), Pretoma Contents Page Charity information 3 Report of the Trustees 4 1. About us and our public benefit 4 2. Objectives and activities for public benefit 6 3. Assessing our performance and achievements 11 4. Our plans for the future to continue to deliver benefit to the public 13 5. Financial review 14 6. Structure, governance and management 14 7. Statement of Trustees’ responsibilities 16 Financial overview 18 Statement of financial activities for the year ended 31 March 2009 18 Balance sheet at 31 March 2009 19 From top Green turtles (Sri Lanka), Scarlet macaws (Guatemala), Whale sharks (Costa Rica) Annual Review 2009 www.bbc.co.uk/bbcwildlifefund Charity information Chairman Bernard Mercer Company registration number 6238115 Deputy Chairman Neil Nightingale Registered charity number 1119286 Treasurer Heather Woods née Brindley Registered office British Broadcasting Corporation Trustees Toby Aykroyd 201 Wood Lane Yogesh Chauhan London W12 7TS John Burton (until 23 July 2008) Auditors Mazars LLP Sarah Ridley Times House Shyam Parekh Throwley Way Georgina Domberger Sutton Secretary Melissa Price (until 23 July 2008) Surrey SM1 4QJ Amy Ely Bankers HSBC Project Manager Lydia Thomas (until 3 April 2009) Regional Services Centre Europe PO Box 125 2nd Floor, 62-76 Park Street London SE1 9DZ Solicitors Farrer & Co 66 Lincoln’s Inn Fields London WC2A 3LH Above Elephant water hole, Kipsing, Kenya Annual Review 2009 www.bbc.co.uk/bbcwildlifefund About us and our public benefit Our objects What we do The BBC Wildlife Fund was set up in 2007 by the BBC to help pro- The BBC Wildlife Fund is a charitable organisation that raises funds tect endangered species around the world and in the UK, identifying from the public to help conserve and protect endangered species not only the most endangered animals on the planet but also those and the habitats on which they depend. -

The “Ambiguity” Fallacy

\\jciprod01\productn\G\GWN\88-5\GWN502.txt unknown Seq: 1 2-SEP-20 11:10 The “Ambiguity” Fallacy Ryan D. Doerfler* ABSTRACT This Essay considers a popular, deceptively simple argument against the lawfulness of Chevron. As it explains, the argument appears to trade on an ambiguity in the term “ambiguity”—and does so in a way that reveals a mis- match between Chevron criticism and the larger jurisprudence of Chevron critics. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................. 1110 R I. THE ARGUMENT ........................................ 1111 R II. THE AMBIGUITY OF “AMBIGUITY” ..................... 1112 R III. “AMBIGUITY” IN CHEVRON ............................. 1114 R IV. RESOLVING “AMBIGUITY” .............................. 1114 R V. JUDGES AS UMPIRES .................................... 1117 R CONCLUSION ................................................... 1120 R INTRODUCTION Along with other, more complicated arguments, Chevron1 critics offer a simple inference. It starts with the premise, drawn from Mar- bury,2 that courts must interpret statutes independently. To this, critics add, channeling James Madison, that interpreting statutes inevitably requires courts to resolve statutory ambiguity. And from these two seemingly uncontroversial premises, Chevron critics then infer that deferring to an agency’s resolution of some statutory ambiguity would involve an abdication of the judicial role—after all, resolving statutory ambiguity independently is what judges are supposed to do, and defer- ence (as contrasted with respect3) is the opposite of independence. As this Essay explains, this simple inference appears fallacious upon inspection. The reason is that a key term in the inference, “ambi- guity,” is critically ambiguous, and critics seem to slide between one sense of “ambiguity” in the second premise of the argument and an- * Professor of Law, Herbert and Marjorie Fried Research Scholar, The University of Chi- cago Law School. -

Begging the Question/Circular Reasoning Caitlyn Nunn, Chloe Christensen, Reece Taylor, and Jade Ballard Definition

Begging the Question/Circular Reasoning Caitlyn Nunn, Chloe Christensen, Reece Taylor, and Jade Ballard Definition ● A (normally) comical fallacy in which a proposition is backed by a premise or premises that are backed by the same proposition. Thus creating a cycle where no new or useful information is shared. Universal Example ● “Pvt. Joe Bowers: What are these electrolytes? Do you even know? Secretary of State: They're... what they use to make Brawndo! Pvt. Joe Bowers: But why do they use them to make Brawndo? Secretary of Defense: [raises hand after a pause] Because Brawndo's got electrolytes” (Example from logically fallicious.com from the movie Idiocracy). Circular Reasoning in The Crucible Quote: One committing the fallacy: Elizabeth Hale: But, woman, you do believe there are witches in- Explanation: Elizabeth believes that Elizabeth: If you think that I am one, there are no witches in Salem because then I say there are none. she knows that she is not a witch. She doesn’t think that she’s a witch (p. 200, act 2, lines 65-68) because she doesn’t believe that there are witches in Salem. And so on. More examples from The Crucible Quote: One committing the fallacy: Martha Martha Corey: I am innocent to a witch. I know not what a witch is. Explanation: This conversation Hawthorne: How do you know, then, between Martha and Hathorne is an that you are not a witch? example of begging the question. In Martha Corey: If I were, I would know it. Martha’s answer to Judge Hathorne, she uses false logic. -

Some Common Fallacies of Argument Evading the Issue: You Avoid the Central Point of an Argument, Instead Drawing Attention to a Minor (Or Side) Issue

Some Common Fallacies of Argument Evading the Issue: You avoid the central point of an argument, instead drawing attention to a minor (or side) issue. ex. You've put through a proposal that will cut overall loan benefits for students and drastically raise interest rates, but then you focus on how the system will be set up to process loan applications for students more quickly. Ad hominem: Here you attack a person's character, physical appearance, or personal habits instead of addressing the central issues of an argument. You focus on the person's personality, rather than on his/her ideas, evidence, or arguments. This type of attack sometimes comes in the form of character assassination (especially in politics). You must be sure that character is, in fact, a relevant issue. ex. How can we elect John Smith as the new CEO of our department store when he has been through 4 messy divorces due to his infidelity? Ad populum: This type of argument uses illegitimate emotional appeal, drawing on people's emotions, prejudices, and stereotypes. The emotion evoked here is not supported by sufficient, reliable, and trustworthy sources. Ex. We shouldn't develop our shopping mall here in East Vancouver because there is a rather large immigrant population in the area. There will be too much loitering, shoplifting, crime, and drug use. Complex or Loaded Question: Offers only two options to answer a question that may require a more complex answer. Such questions are worded so that any answer will implicate an opponent. Ex. At what point did you stop cheating on your wife? Setting up a Straw Person: Here you address the weakest point of an opponent's argument, instead of focusing on a main issue. -

Chapter 4: INFORMAL FALLACIES I

Essential Logic Ronald C. Pine Chapter 4: INFORMAL FALLACIES I All effective propaganda must be confined to a few bare necessities and then must be expressed in a few stereotyped formulas. Adolf Hitler Until the habit of thinking is well formed, facing the situation to discover the facts requires an effort. For the mind tends to dislike what is unpleasant and so to sheer off from an adequate notice of that which is especially annoying. John Dewey, How We Think Introduction In everyday speech you may have heard someone refer to a commonly accepted belief as a fallacy. What is usually meant is that the belief is false, although widely accepted. In logic, a fallacy refers to logically weak argument appeal (not a belief or statement) that is widely used and successful. Here is our definition: A logical fallacy is an argument that is usually psychologically persuasive but logically weak. By this definition we mean that fallacious arguments work in getting many people to accept conclusions, that they make bad arguments appear good even though a little commonsense reflection will reveal that people ought not to accept the conclusions of these arguments as strongly supported. Although logicians distinguish between formal and informal fallacies, our focus in this chapter and the next one will be on traditional informal fallacies.1 For our purposes, we can think of these fallacies as "informal" because they are most often found in the everyday exchanges of ideas, such as newspaper editorials, letters to the editor, political speeches, advertisements, conversational disagreements between people in social networking sites and Internet discussion boards, and so on. -

The Trespass Fallacy in Patent Law , 65 Fla

Florida Law Review Volume 65 | Issue 6 Article 1 October 2013 The rT espass Fallacy in Patent Law Adam Mossoff Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/flr Part of the Intellectual Property Commons, and the Property Law and Real Estate Commons Recommended Citation Adam Mossoff, The Trespass Fallacy in Patent Law , 65 Fla. L. Rev. 1687 (2013). Available at: http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/flr/vol65/iss6/1 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by UF Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida Law Review by an authorized administrator of UF Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mossoff: The Trespass Fallacy in Patent Law Florida Law Review Founded 1948 VOLUME 65 DECEMBER 2013 NUMBER 6 ESSAYS THE TRESPASS FALLACY IN PATENT LAW Adam Mossoff∗ Abstract The patent system is broken and in dire need of reform; so says the popular press, scholars, lawyers, judges, congresspersons, and even the President. One common complaint is that patents are now failing as property rights because their boundaries are not as clear as the fences that demarcate real estate—patent infringement is neither as determinate nor as efficient as trespass is for land. This Essay explains that this is a fallacious argument, suffering both empirical and logical failings. Empirically, there are no formal studies of trespass litigation rates; thus, complaints about the patent system’s indeterminacy are based solely on an idealized theory of how trespass should function, which economists identify as the “nirvana fallacy.” Furthermore, anecdotal evidence and other studies suggest that boundary disputes between landowners are neither as clear nor as determinate as patent scholars assume them to be. -

What Is Racial Domination?

STATE OF THE ART WHAT IS RACIAL DOMINATION? Matthew Desmond Department of Sociology, University of Wisconsin—Madison Mustafa Emirbayer Department of Sociology, University of Wisconsin—Madison Abstract When students of race and racism seek direction, they can find no single comprehensive source that provides them with basic analytical guidance or that offers insights into the elementary forms of racial classification and domination. We believe the field would benefit greatly from such a source, and we attempt to offer one here. Synchronizing and building upon recent theoretical innovations in the area of race, we lend some conceptual clarification to the nature and dynamics of race and racial domination so that students of the subjects—especially those seeking a general (if economical) introduction to the vast field of race studies—can gain basic insight into how race works as well as effective (and fallacious) ways to think about racial domination. Focusing primarily on the American context, we begin by defining race and unpacking our definition. We then describe how our conception of race must be informed by those of ethnicity and nationhood. Next, we identify five fallacies to avoid when thinking about racism. Finally, we discuss the resilience of racial domination, concentrating on how all actors in a society gripped by racism reproduce the conditions of racial domination, as well as on the benefits and drawbacks of approaches that emphasize intersectionality. Keywords: Race, Race Theory, Racial Domination, Inequality, Intersectionality INTRODUCTION Synchronizing and building upon recent theoretical innovations in the area of race, we lend some conceptual clarification to the nature and dynamics of race and racial domination, providing in a single essay a source through which thinkers—especially those seeking a general ~if economical! introduction to the vast field of race studies— can gain basic insight into how race works as well as effective ways to think about racial domination. -

Prehistoric Planet 3D PUBLISHING PACK for MUSEUM USE on SOCIAL PLATFORMS

Walking with Dinosaurs: Prehistoric Planet 3D PUBLISHING PACK FOR MUSEUM USE ON SOCIAL PLATFORMS COMPANY CONFIDENTIAL Using this pack This pack outlines content examples for posts which fall under 7 content “pillars” (Continuing the Story, Box Office Promotion, Leveraging Other Assets, Branded Infographics, Branded Fact Files, Conversation Tools, and Behind-the-Scenes Videos). The copy provided with each post is recommended but not compulsory. Museums may want to add promotional messaging, although we’d advise not over-saturating content with these messages. Understanding the assets Each complete piece of content has been packaged individually to allow the publishing process to be as simple and efficient as possible. The platform(s) the copy is designed for (Facebook, Instagram, Proposed copy to be used in Image Twitter) conjunction with adjacent image Image no. COMPANY CONFIDENTIAL Understanding the assets cont. Beneath each example post in this PDF will be a figure number which corresponds to an asset found in the “Publishing Assets” folder also supplied in this pack. In the “Publishing Assets” folder this figure number will be followed by a set of letters which outline the platforms the content is optimised for; FB = Facebook TW = Twitter INSTA = Instagram COMPANY CONFIDENTIAL Publishing best practices To extract the optimum performance out of this Publishing Pack, theAudience advises the following best publishing practises. Following these principles will maximise the content’s potential in engaging an audience on social. Keep copy as short as possible theAudience has proposed copy to accompany each individual image in this pack. This copy can be used as an example with sales messages attached (or can be changed completely) although we would advise not directly marketing the film in more than 60% of the content as sales messages can lose traction when used at a high frequency on social. -

Awe-Inspiring Adventure Take the Trip of a Lifetime Through the Wildest Continent on Earth

DECEMBER 2015 – JANUARY 2016 Sparks!A Newsletter for Members and Friends of the Museum of Science Inside This Issue • Wild Waters of Africa • Computer Science Fun • Member Perks Awe-Inspiring Adventure Take the trip of a lifetime through the wildest continent on Earth. large and environmentally diverse place, Africa is surrounded by vast oceans and seas and features rainforests, the world’s A largest waterfall, and countless rivers. Water is the lifeline for this continent’s wildlife, as you’ll witness in the new giant-screen film, BBC Earth’s Wild Africa, now showing on the IMAX® Dome screen. Nations of Wonder Dive into the Red Sea and visit spectacular coral reefs that are home to an array of species. Travel thousands of feet into the air to Kenya’s snow-covered mountains. Between these elevation extremes, you’ll see the striking contrasts of deserts that border oceans, erupting volcanoes, the enormous Victoria Falls, wide-open savannas, and many other eye-catching landscapes. Along this journey through 12 of the nations that make up Africa, you’ll meet a large cast of real-life animal characters, including a family of mountain gorillas in a Rwandan forest, hundreds of thousands of flamingos performing a unique mating ritual in Kenya’s Continued on next page Continued from cover volcanic Lake Bogoria, hungry crocodiles waiting for the annual wildebeest migration to water holes in the Serengeti, elephants desperately searching for water, and snakes and lizards in Namibia’s barren desert finding water in their food. Your odyssey concludes in the swamps of southern Africa, where water’s ultimate role as a lifesaver is on display. -

Late 1960'S - Early 1970'S

Late 1960's - Early 1970's The birth of heavy metal. Groups like Black Sabbath, Led Zeppelin and Deep Purple were the first heavy metal bands. Late 1970's The rise of the New Wave of British Heavy Metal. Bands like Iron Maiden and Judas Priest become very popular. 1978 Van Halen released their debut album. This began the Los Angeles/Sunset Strip scene, and many bands would come out of this era, including Motley Crue and Quiet Riot. The so called "hair bands" like Poison, Warrant and Ratt came from that scene as well. The Who's Keith Moon died. Bands formed this year: Dokken, Ratt, Whitesnake A sample of heavy metal albums released in 1978: Black Sabbath - Never Say Die Judas Priest - Stained Class UFO - Obsession 1979 The German band Accept releases their self-titled debut album. They are considered to be the first European power metal band. Ozzy Osbourne was fired from Black Sabbath and replaced by Ronnie James Dio. Bands formed this year: Europe, Hanoi Rocks, Trouble and Venom. A sample of heavy metal albums released in 1979: AC/DC - Highway To Hell Judas Priest - Hell Bent For Leather Led Zeppelin - In Through The Out Door Kiss - Dynasty Saxon - Saxon Scorpions - Lovedrive 1980 Best Heavy Metal Album Of 1980: AC/DC - Back In Black AC/DC lead singer Bon Scott dies and is replaced by Brian Johnson. Also Led Zeppelin drummer John Bonham dies. Bands formed this year: Manowar, Mercyful Fate, Overkill A sample of heavy metal albums released in 1980: Angel Witch - Angel Witch Black Sabbath - Heaven And Hell Def Leppard - On Through The Night Diamond Head - Lightning To The Nations Iron Maiden - Iron Maiden Judas Priest - British Steel Motorhead - Ace Of Spades Ozzy Osbourne - Blizzard Of Ozz Saxon - Wheels Of Steel 1981 Best Heavy Metal Album Of 1981: Motley Crue - Too Fast For Love Venom's first album was released, beginning the genre of black metal.