AS AUEOR .535 As SUBJECT;

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Horan Family Diaspora Since Leaving Ireland 191 Years Ago

A Genealogical Report on the Descendants of Michael Horan and Mary Minnock by A.L. McDevitt Introduction The purpose of this report is to identify the descendants of Michael Horan and Mary Minnock While few Horans live in the original settlement locations, there are still many people from the surrounding areas of Caledon, and Simcoe County, Ontario who have Horan blood. Though heavily weigh toward information on the Albion Township Horans, (the descendants of William Horan and Honorah Shore), I'm including more on the other branches as information comes in. That is the descendants of the Horans that moved to Grey County, Ontario and from there to Michigan and Wisconsin and Montana. I also have some information on the Horans that moved to Western Canada. This report was done using Family Tree Maker 2012. The Genealogical sites I used the most were Ancestry.ca, Family Search.com and Automatic Genealogy. While gathering information for this report I became aware of the importance of getting this family's story written down while there were still people around who had a connection with the past. In the course of researching, I became aware of some differences in the original settlement stories. I am including these alternate versions of events in this report, though I may be personally skeptical of the validity of some of the facts presented. All families have myths. I feel the dates presented in the Land Petitions of Mary Minnock and the baptisms in the County Offaly, Ireland, Rahan Parish registers speak for themselves. Though not a professional Genealogist, I have the obligation to not mislead other researchers. -

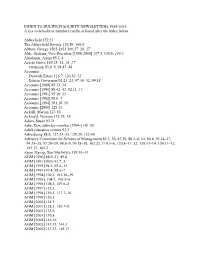

INDEX to DULWICH SOCIETY NEWSLETTERS 1989-2014 a Key to Newsletter Numbers Can Be at Found After the Index Below

INDEX TO DULWICH SOCIETY NEWSLETTERS 1989-2014 A key to newsletter numbers can be at found after the index below. Abbeyfield 152.31 The Abbeyfield Society 119.29, 160.8 Abbott, George 1562-1633 166.27–28, 27 Able, Graham, Vice-President [1998-2000] 117.9, 138.8, 140.3 Abrahams, Adam 85.3–4 Acacia Grove 169.25–31, 26–27 extension 93.8–9, 94.47–48 Accounts Dulwich Estate 116.7, 120.30–32 Estates Governors 92.21–23, 97.30–32, 99.18 Accounts [1989] 85.33–34 Accounts [1990] 88.42–43, 92.11–13 Accounts [1991] 95.10–13 Accounts [1992] 98.6–7 Accounts [1994] 101.18–19 Accounts [2000] 125.11 Ackrill, Marion 123.30 Ackroyd, Norman 132.19, 19 Adam, Susan 93.31 Adie, Don, sub-ctee member [1994-] 101.20 Adult education centres 93.5 Advertising 88.8, 127.33–35, 129.29, 132.40 Advisory Committee for Scheme of Management 85.3, 20, 87.26, 88.5–6, 12, 90.8, 92.14–17, 94.35–38, 97.29–39, 98.8–9, 99.18–20, 102.32, 114.5–6, 120.8–11, 32, 130.13–14, 134.11–12, 145.13, 165.3 Agent Zigzag, Ben MacIntyre 159.30–31 AGM [1990] 88.9–11, 89.6 AGM [1991] 90.9, 91.2, 5 AGM [1992] 94.5, 95.6–13 AGM [1993] 97.4, 98.6–7 AGM [1994] 100.5, 101.16–19 AGM [1995]. 104.3, 105.5–6 AGM [1996] 108.5, 109.6–8 AGM [1997] 112.5 AGM [1998] 116.5, 117.7–10 AGM [1999] 120.5 AGM [2000] 124.9 AGM [2001] 128.5, 130.7–8 AGM [2002] 132.6 AGM [2003] 136.8 AGM [2004] 140.16 AGM [2005] 143.33, 144.3 AGM [2006] 147.33, 148.17 AGM [2007] 152.2, 9 AGM [2008] 156.21 AGM [2009] 160.6 AGM [2010] 164.12 AGM [2011] 168.5 AGM [2012] 172.6 AGM [2013] 176.5 Air Training Corps Squadron 153.6–7 Aircraft -

Schomberg" from Liverpool to Melbourne in 1855

DIARY OF THOMAS ANGOVE Passenger on the Clipper ship "Schomberg" from Liverpool to Melbourne in 1855. Extract from the remains of his Diary. NB. This was the last voyage of the Colonial Clipper, Schomberg. In 1855, the Schomberg, skippered by the tough, courageous and quick-tempered Captain James “Bully” Forbes, set forth to establish a new England-Australia sailing record. When the ship he once described as "the noblest that ever floated on water" was drifting to disaster on the rocks west of Bass Strait, he strangely seemed to lose interest and opted for the latter destination in his famous signal - "Melbourne or Hell In Sixty Days". Why we do not know. (From BHP "History of the Bass Strait" Series.) - - - One of the men is much elevated by being made President of the Mess and he does all the dirty work such as clean knives and forks, empty the slops for the ladies, etc. and this he does with pleasure to be called "Mr President". The other, the filibuster of the lot, has been exposed to the destroying hand of time for his hair, which was once a fine carroty colour has flown from the top of his head and has reappeared on each side of his face and chin in abundance which puts one in mind of a Southcotte. The other is half-woman and does not figure so high as the former. The weather is truly delightful with a nice breeze. We are in the Trade Winds and tomorrow we hope to be in the Tropics. Our latitude today is 25 17`. -

William Duthie Jnr. &

2021 – v1 William Duthie jnr. & Co., Shipbuilders, UPPER DOCK, ABERDEEN, 1856 TO 1870. INCLUDES INFORMATION ON DUTHIE & COCHAR, SHIPBUILDERS, MONTROSE 1854 TO 1856. STANLEY BRUCE William Duthie Jnr. & Co., Shipbuilders, Upper Dock, Aberdeen, 1856 to 1870. Stanley Bruce, 2021-v1 . Due to the age of the photographs, drawings and paintings in this book they are all considered to be out of copyright, however where the photographer, artist or source of the item is known it has been stated directly below it. For any stated as ‘Unknown’ I would be very happy for you to get in touch if you know the artist or photographer. Cover photograph – The 3-masted ship 'Alexander Duthie' moored at Gravesend, U.K., 1875. (Photographer unknown, from the A. D. Edwardes Collection, courtesy of the State Library of South Australia, Ref: PRG 1373/3/3). This book has been published on an entirely non-profit basis and made available to all free of charge as a pdf. The aim of the book is to make the history of vessels built by William Duthie Jnr. & Co. available to a wider audience. There is much available on the internet, especially on www.aberdeenships.com, but unfortunately what’s currently available is scattered and doesn’t give the full picture. If you have any comments regarding this book, or any further information, especially photographs or paintings of vessels where I have none. It would be historically good to show at least one for each vessel, and since this is an electronic edition it will be possible to update and include any new information. -

Berghahn Books

Berghahn Books Turpin Distribution The Enemy on Display The Second World War in Eastern European Museums Description: Eastern European museums represent traumatic events of World War II, such as the Siege of Leningrad, the Warsaw Uprisings, and the Bombardment of Dresden, in ways that depict the enemy in particular ways. This image results from the interweaving of historical representations, cultural stereotypes and beliefs, political discourses, and the dynamics of exhibition narratives. This book presents a useful methodology for examining museum images and provides a critical analysis of the role historical museums play in the contemporary world. As the catastrophes of World War II still exert an enormous influence on the national identities of Russians, Poles, and Germans, museum exhibits can thus play an important role in this process. ...the book highlights the fascinating issue of displaying war, and, through display, defining and exposing certain concepts of national and local identity. In that sense the volume is an important contribution to the growing literature on Central and East European museums in particular, and the issue of presentation of war in museums in general. Canadian Slavonic Papers Certain key passages make very important and significant points about the depiction of the past in the recently ‘museified’ Eastern European countries. The focus on Dresden, Warsaw, ISBN: 9781785337604 and Leningrad/St. Petersburg works very well as each thematically driven case study complements each other and offers new ways of understanding images of the enemy in Published: 30-12-17 historicized museum depictions. Keir Reeves, Monash University Price: £ 19.00 About Author/s: Author/s: Zuzanna Bogumi?, Joanna Wawrzyniak, Tim Buchen, Christian Zuzanna Bogumi? is Assistant Professor at the Maria Grzegorzewska Academy of Special Education in Warsaw and a member of the Social Memory Laboratory at the Institute of Ganzer and Maria Senina Sociology, University of Warsaw. -

Greyhounds Ofthe Sea

Greyhounds ofthe Sea rU4'-o ~.., , t'",~J • n6...... ;;~ jef7- (I817');/~~ (~ ,I":ioI~~' '.<J . ~., ".~, ~ tt-"L?' J. '! 1 t-~. (0''''' /? ('tt- h' /"";i tZ-:'~ l?S I &-,"~ u ~ . i'~ <.. ~H.. -?1 (.. u.-~ .L..4.. .... M.I~. ,,~ ~ /1 Jtrt..,# l2.. • r A 't" ....-? /.,;t. >- .. /fa..; ~4Mfol SAMUEL RUSSEL Letter written on board while the ship Is in the Indian Ocean enroute to Canton, ('hinn. The following quotes arc from thL'; letter which is dated Aug. 9, 1848: "/ sailed /rom N York on thefirstofJune- this shipisoneofthebestthatsailsframNYork -Ihaveafine ship good state room, welive/irstrate. haveourwineeveryday _ OurCaptain, T.D. Palmerisa Jineman -Ishall return in this ship - Wearenowwilhin two dayssail0/Anger-which/stand is about eighteen hundred miIesjrom Canton, wehopeUJ makeAnger the lastofthe week _ we have not seen land sincewe lost sightojournativeland, 1think we willmakelhepa&8agej'rom N.Y. to Canton in Eighty three dall8 a dlstanu a/seventeen thousand milt!3 _ Uwe do it in thiA time it will be the shortellt passage ever made It Signed "Henry Kellogg. It The letter came into Boston on January 8, 1849 almost 5 months to the day since it was written. It was rated a .. a ship letter "7" - 5 cents postage and 2 cents ship fee. r::;:;::::;[';'? )-~) ~ ';/;") ~:;~';:7~ ". ; t I r Greyhounds ofthe Sea ./ , • ) , , ( " / • t • ./ /,(" • ,; { 'It''r //1' ,/-/< . ,- ~II 't:/~A 1 'J".N? . ./. ". 7 i/ i!-v F, /1' ..,'''7 7 -/ I MERl\tAJD I3ritish clipper in the Au....tralian - Liverpool trade. Carried from Melbourne, Victoria to Scotland December 15, 1856 to March 10, 1857. - NORNA British clipper in the Australian - Livcrpoollrade. -

The Irish Genealogist

THE IRISH GENEALOGIST OFFICIAL ORGAN OF THE IRISH GENEALOGICAL RESEARCH SOCIETY Vol. 13, No. 4 2013 CONTENTS Chairman’s Report 2013 Steven C. ffeary-Smyrl 273 Tributes: Captain Graham H. Hennessy, RM; Mona Germaine Dolan 276 New Vice Presidents – Mary Casteleyn, Peter Manning, Rosalind McCutcheon 281 New Fellows – Terry Eakin, Claire Santry, Jill Williams 285 Spanish Archives of Primary Source Material for the Irish: Part II Samuel Fannin 288 The de la Chapelle or Supple or de Capel-Brooke families of Cork, Limerick and Kerry Paul MacCotter 311 A Census of the Half Parish of Ballysadare, Co. Sligo, c.1700 R. Andrew Pierce 344 An Account of pensions which stood charged on the Civil List of Ireland in February 1713/1714. Mary Casteleyn 347 The Will of John Butler of Kilcash, County Tipperary John Kirwan 375 Millerick: A History/Spirituality of an Irish Surname Martin Millerick 385 The Kirwans of Galway City and County and of the County of Mayo Michael Kirwan 389 An Irish Scandal: The Marriage Breakdown of Lord and Lady George Beresford Elaine Lockhart 410 The Duffy Publishing Family John Brennan 426 Ireland – Maritime Canada – New England Terrence M. Punch 436 The Catholic Registers of Killea and Crooke, Co. Waterford Peter Manning 443 Reviews 458 Report and Financial Statements – Year ended 31 December 2012 462 Table of Contents, Vol. 13 465 Submissions to the Journal – style rules 467 How to find our library at The Society of Genealogists IBC Composed and printed in Great Britain by Doppler Press 5 Wates Way, Brentwood, Essex CM15 9TB Tel: 01634 364906 ISSN 0306-8358 © Irish Genealogical Research Society THE LIBRARY OF THE IRISH GENEALOGICAL RESEARCH SOCIETY IS AT THE SOCIETY OF GENEALOGISTS, LONDON. -

The Life-Boat

THE LIFE-BOAT, OR JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL LIFE-BOAT INSTITUTION. (ISSBBD Q0ABTEBLT.) You VIII.—No. 80,] MAI IST, 1871, [Pmcz Is. AT the ANNUAL GENEBAI/ MEET/NO of the BOYAI. NATIONAL LIFE-BOAT INSTITUTION, held at the London Tavern OB Tuesday, the 14th day of March, 1871, His Grace the DUKE of HoBTH«MBE»i»AjsrD, P.O., D.O.L., President of the Institution, in the Chair, the following Beport of the Committee was read by the Secretary:— ANNUAL BEPOBT. The transactions of the Institution Osr this the forty-seventh anniversary of during the year may be thus summarized: the establishment of the EOYAL NATIONAL Life-boats,— Since the last Beport four- LIFK-BOAT IMSTCTCMOH, for the Preserva- teen new life-boats have been placed on the tion of Life from Shipwreck, its Committee coast, and stationed at the following of Management place before its supporters places : — and the British 3?ublie their Annual ENGLAND. Beporf. DUBHAM ..... Seaham. In doing so they beg to return their LINCOLNSHIRE. Chapel. warm thanks to all those who, by their NOKFOI.K ..... Palling. SUFFOLK ..... Gorleston. donations and annual subscriptions, haTe Pakefleld. enabled them successfully to prosecute the Kessingland. important national dnty which they haTe Thorpenesg, Aldborongh. undertaken, and they desire to express KENT ...... Kiagssfewne. their gratitude for the Divine Messing I>EVONSIUBE .... Morte Bay. •which has rested on their labours. It is true that, in reference to the funds, SCOTLAHD. a considerable diminution has occurred in BacHe. Banff. the contributions of the year. The Com- FOBFAS .... mittee, however, feel sure that this fact IEELAND. -

De Ontwikkelingsgang Der Nederlandsche Letterkunde. Deel 5: Geschiedenis Der Nederlandsche Letterkunde Van De Republiek Der Vereenigde Nederlanden (3)

De ontwikkelingsgang der Nederlandsche letterkunde. Deel 5: Geschiedenis der Nederlandsche letterkunde van de Republiek der Vereenigde Nederlanden (3) J. te Winkel bron Jan te Winkel, De ontwikkelingsgang der Nederlandsche letterkunde V. Geschiedenis der Nederlandsche letterkunde van de Republiek der Vereenigde Nederlanden (3). De erven F. Bohn, Haarlem 1924, tweede druk. Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/wink002ontw05_01/colofon.htm © 2002 dbnl 2 Vierde tijdvak. (vervolg). De verfransching der letteren. 1680-1780. (vervolg). J. te Winkel, De ontwikkelingsgang der Nederlandsche letterkunde.Deel 5: Geschiedenis der Nederlandsche letterkunde van de Republiek der Vereenigde Nederlanden (3) 3 XI. Willem III gehekeld en verheerlijkt. Bij den aanvang van dit tijdperk was Prins Willem III bijna onbeperkt leider van onze binnen- en buitenlandsche politiek. Die macht had hij te danken aan de gelukkige uitkomst van zijn krijgsbeleid in den, aanvankelijk wanhopig schijnenden, strijd tegen eene overmacht als die van Lodewijk XIV, en aan de goede verstandhouding, die er met Engeland ontstaan was door zijn huwelijk met Maria Stuart, de oudste dochter van Jacobus, hertog van York, en vermoedelijk troonopvolger van zijn broeder Karel II. Wel had hij niet kunnen verhinderen, dat de Staten-Generaal in 1678 tegen zijn zin met Lodewijk XIV te Nijmegen vrede hadden gesloten en dat die vrede ook door onze dichters was bejubeld, o.a. ook door KATHARINA LESCAILJE, die daarbij merkwaardig getrouw taal, toon en dichtvorm van Vondel's zang op den vrede van Munster wist te volgen, maar gedurende het tienjarig vredestijdperk, dat nu volgde, wist Willem III toch zijn wil grootendeels te doen zegevieren, hetzij door de verheffing zijner gunstelingen en oogendienaars tot hooge staatsambten, hetzij, en niet zelden, door wetsverzetting in steden, die zich niet in allen deele naar zijn wil schikten. -

Catalogue 150 ~Spring & Summer 2018

Marine & Cannon Books Celebrating 35 Years of Bookselling 1983 ~ 2018 Catalogue 150 ~Spring & Summer 2018 NAVAL ~ MARITIME Fine & Rare MILITARY & AVIATION Antiquarian & BOOKSELLERS Out-of-Print Est. 1983 Books & Ephemera Front Cover Illustration : Caricature of ADMIRAL SIR GEORGE YOUNG (1732-1810) Drawn by Cooke & Published by Deighton, Charing Cross, January 1809. Item No. V457 MARINE & CANNON BOOKS CATALOGUE 150 {Incorporating Eric Lander Est. 1959 & Attic Books Est. 1995} Proprietors: Michael & Vivienne Nash and Diane Churchill-Evans, M.A. Naval & Maritime Dept: Military & Aviation Dept: Marine & Cannon Books Marine & Cannon Books “Nilcoptra” Square House Farm 3 Marine Road Tattenhall Lane HOYLAKE TATTENHALL Wirral CH47 2AS Cheshire CH3 9NH England England Tel: 0151 632 5365 Tel: 01829 771 109 Fax: 0151 632 6472 Fax: 01829 771 991 Em: [email protected] Em: [email protected] Established: 1983. Website : www.marinecannon.com VAT Reg. N: GB 539 4137 32 When ordering NAUTICAL items only, please place your order with our Naval & Maritime Department in Hoylake. If you are ordering MILITARY and/or AVIATION items only, please place your order with our Military & Aviation Department in Tattenhall. However, when ordering a mixture of NAUTICAL and MILITARY/AVIATION items, you need only contact Hoylake. This is to save you having to contact both departments. For a speedier service we recommend payment by Credit or Debit Card [See details below] or via our PAYPAL account - [email protected] For UK customers, parcels will either be sent Royal Mail or by Parcelforce. For OVERSEAS customers, we send AIRMAIL to all European destinations, and either AIRMAIL or SURFACE MAIL to the rest of the world, as per your instructions. -

The Liverpool Nautical Research Society TRANSACTIONS

The Liverpool Nautical Research Society TRANSACTIONS VOLUME VII * 1952-53 With the compliments oj United Typewriters Company , 16 3 Dale Street, Liverpool 2 CENtral 2212/3 ILLUSTRATED ANNUAL • On sale at every Port * in the country. PRICE ONE SHILLING 42 STANLEY STREET, LIVERPOOL, I BOOKS ABOUT SHIPS Merchant Ships: British Built Volume If Liners and their Recognition An illustrated Register of ships of ap by Laurence Dunn proximately 300 gross tons and upwards Every passenger liner of over 10,000 built in British shipyards in 1953. Contents: tons in the world. Over 170 photographs Technical developments, hull, machinery, and over 100 drawings of ships and their equipment, with representative plans of distinguishing features. 12s. 6d. net ships-Ships listed by tonnage-Ships Ship Recognition : Warships listed by machinery-The Register of by Laurence Dunn Owners, classifications, dimensions, build Covering the N.A.T.O. powers. Very ers, engines and brief constructional highly illustrated with photographs and details of each ship built in 1953. identification drawings. 12s. 6d. net In the new format for Volume 11 over 80 ships representative of every type and Ship Recognition : Merchant Ships purpose are illustrated by large photo by Laurence Dunn graphs (Si x 4t) printed on heavy art With over 260 carefully selected photo paper so that every detail shows in graphs and drawings by the author. reproduction. 12s. 6d. net Published annually. 21 s. net Yachts and their Recognition Flags, Funnels and Hull Colours by Adlard Coles and D. Phillips-Birt by Colin Stewart With over 100 photographs and draw Over 450 shipping companies of the ings and nearly 200 burgees in full colour. -

Stevenson, Conrad and the Proto-Modernist Novel Eric Massie

UNIVERSITY OF STIRLING Stevenson, Conrad and the Proto-Modernist Novel Eric Massie A Doctoral Thesis Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Stirling February 2002 ©Eric Massie 2002 Abstract This thesis argues that Robert Louis Stevenson's South Seas writings locate him alongside Joseph Conrad on the 'strategic fault line' described by the Marxist critic Fredric Jameson that delineates the interstitial area between nineteenth-century adventure fiction and early Modernism. Stevenson, like Conrad, mounts an attack on the assumptions of the grand narrative of imperialism and, in texts such as 'The Beach of Falesa' and The Ebb Tide, offers late-Victorian readers a critical view of the workings of Empire. The present stud)' seeks to analyse the common interests of two important writers as they adopt innovative literary methodologies within, and in response to, the context of changing perceptions of the effects of European influence upon the colonial subject. Acknowledgements lowe a huge debt of gratitude to my Supervisor, Professor Douglas Mack for his advice and support during the course of the research and subsequent writing up of this thesis. Professor Mack has encouraged my tentative steps in scholarship and has gently curbed my excesses. The debt lowe him is immeasurable. Professor Neil Keeble, Head of Department of English Studies during my period of research at the University of Stirling, has been generous in his support of my work in a number of ways. He encouraged me to develop and to teach an Honours Option: The Fiction ofRobert Louis Stevenson which has proved to be a successful component of the Departmental portfolio.