Liverpool Nautical Research Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Map Matters 1

www.australiaonthemap.org.au I s s u e Map Matters 1 Issue 19 November 2012 Inside this issue Welcome to the "Spring" 2012 edition of Map Matters, News the newsletter of the Australia on the Map Division of the Cutty Sark is back! Australasian Hydrographic Society. A Star to Steer Her By Johann Schöner on the Web Arrowsmith's Australian If you have any contributions or suggestions for Maps Map Matters, you can email them to me at: Rupert Gerritsen awarded the Dorothy [email protected], or post them to me at: Prescott Prize GPO Box 1781, Canberra, 2601 When Did the Macassans Start Coming to Northern Frank Geurts Australia? Editor Projects update Members welcome Contacts How to contact the AOTM Division News Cutty Sark is back! On 25 April 2012, near Britain’s National Maritime Museum at historic Greenwich, Queen Elizabeth II reopened Cutty Sark after nearly six years of restoration work, punctuated by the serious fire of 21 May 2007. The Cutty Sark is not only a London icon but also an important artefact in Australian maritime history. She spent 12 years of her working life carrying Australian wool to England. The ship was built in 1869 for one purpose – to bring tea back to London from China quickly. A premium was paid for new season tea so that the first ships back made huge profits for their owners. This led to competition to build faster ships shaped more like elegant racing yachts than cargo carriers. Cutty Sark is a composite ship with a frame of wrought iron and a wooden cladding, built at Dumbarton, Scotland. -

The Horan Family Diaspora Since Leaving Ireland 191 Years Ago

A Genealogical Report on the Descendants of Michael Horan and Mary Minnock by A.L. McDevitt Introduction The purpose of this report is to identify the descendants of Michael Horan and Mary Minnock While few Horans live in the original settlement locations, there are still many people from the surrounding areas of Caledon, and Simcoe County, Ontario who have Horan blood. Though heavily weigh toward information on the Albion Township Horans, (the descendants of William Horan and Honorah Shore), I'm including more on the other branches as information comes in. That is the descendants of the Horans that moved to Grey County, Ontario and from there to Michigan and Wisconsin and Montana. I also have some information on the Horans that moved to Western Canada. This report was done using Family Tree Maker 2012. The Genealogical sites I used the most were Ancestry.ca, Family Search.com and Automatic Genealogy. While gathering information for this report I became aware of the importance of getting this family's story written down while there were still people around who had a connection with the past. In the course of researching, I became aware of some differences in the original settlement stories. I am including these alternate versions of events in this report, though I may be personally skeptical of the validity of some of the facts presented. All families have myths. I feel the dates presented in the Land Petitions of Mary Minnock and the baptisms in the County Offaly, Ireland, Rahan Parish registers speak for themselves. Though not a professional Genealogist, I have the obligation to not mislead other researchers. -

The Travels of Marco Polo

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. http://books.google.com TheTravelsofMarcoPolo MarcoPolo,HughMurray HARVARD COLLEGE LIBRARY FROM THE BEQUEST OF GEORGE FRANCIS PARKMAN (Class of 1844) OF BOSTON " - TRAVELS MAECO POLO. OLIVER & BOYD, EDINBURGH. TDE TRAVELS MARCO POLO, GREATLY AMENDED AND ENLARGED FROM VALUABLE EARLY MANUSCRIPTS RECENTLY PUBLISHED BY THE FRENCH SOCIETY OP GEOGRAPHY AND IN ITALY BY COUNT BALDELLI BONI. WITH COPIOUS NOTES, ILLUSTRATING THE ROUTES AND OBSERVATIONS OF THE AUTHOR, AND COMPARING THEM WITH THOSE OF MORS RECENT TRAVELLERS. BY HUGH MURRAY, F.R.S.E. TWO MAPS AND A VIGNETTE. THIRD EDITION. EDINBURGH: OLIVER & BOYD, TWEEDDALE COURT; AND SIMPKIN, MARSHALL, & CO., LONDON. MDOCCXLV. A EKTERIR IN STATIONERS' BALL. Printed by Oliver & Boyd, / ^ Twseddale Court, High Street, Edinburgh. p PREFACE. Marco Polo has been long regarded as at once the earliest and most distinguished of European travellers. He sur passed every other in the extent of the unknown regions which he visited, as well as in the amount of new and important information collected ; having traversed Asia from one extremity to the other, including the elevated central regions, and those interior provinces of China from which foreigners have since been rigidly excluded. " He has," says Bitter, " been frequently called the Herodotus of the Middle Ages, and he has a just claim to that title. If the name of a discoverer of Asia were to be assigned to any person, nobody would better deserve it." The description of the Chinese court and empire, and of the adjacent countries, under the most powerful of the Asiatic dynasties, forms a grand historical picture not exhibited in any other record. -

Find Kindle < Marco Polo: the Story of the Fasted Clipper

WUK21UQ54KAW / Book » Marco Polo: The Story of the Fasted Clipper Marco Polo: Th e Story of th e Fasted Clipper Filesize: 9.42 MB Reviews Most of these pdf is the best ebook offered. It is probably the most remarkable book i actually have study. Your life period will be transform as soon as you complete reading this pdf. (Albertha Champlin) DISCLAIMER | DMCA BMAWEZGRWI5T Kindle ^ Marco Polo: The Story of the Fasted Clipper MARCO POLO: THE STORY OF THE FASTED CLIPPER Nimbus Publishing, Halifax, 2006. Paperback. Condition: New. 1st Edition. This impressively researched book is the first to present the full story one of the most famous, and certainly the fastest clippers of her time. A novel design built in Saint John, New Brunswick, in 1851, Marco Polo absolutely astounded the maritime world when, in 1852-53, she became the first ship ever to sail from England to Australia and back in under six months and twice around the world in under a year. Over a fieen-year period the ship carried huge numbers of destitute emigrants from Britain to a better life in Australia, on voyages closely followed by the press and many thousands worldwide. The exploits of principal owner James Baines and captain James Nicol Bully Forbes feature strongly in the book two men who easily rank among the most colourful and interesting characters in the entire history of the British merchant marine. Together, Baines, the aggressive, high-rolling entrepreneur, and Forbes, the clever, boastful mariner, were an unbeatable combination, especially when teamed with Marco Polo. This well-illustrated book explains why the ship was so fast, but also places the account in the context of the mid-nineteenth-century shipbuilding boom in British North America, the great Australian Gold Rush in the 1850s, and the mass exodus from Liverpool to Australia of gold seekers and others seeking escape from poverty and disease. -

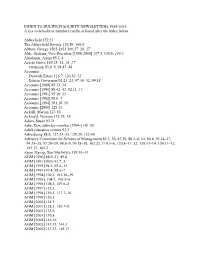

INDEX to DULWICH SOCIETY NEWSLETTERS 1989-2014 a Key to Newsletter Numbers Can Be at Found After the Index Below

INDEX TO DULWICH SOCIETY NEWSLETTERS 1989-2014 A key to newsletter numbers can be at found after the index below. Abbeyfield 152.31 The Abbeyfield Society 119.29, 160.8 Abbott, George 1562-1633 166.27–28, 27 Able, Graham, Vice-President [1998-2000] 117.9, 138.8, 140.3 Abrahams, Adam 85.3–4 Acacia Grove 169.25–31, 26–27 extension 93.8–9, 94.47–48 Accounts Dulwich Estate 116.7, 120.30–32 Estates Governors 92.21–23, 97.30–32, 99.18 Accounts [1989] 85.33–34 Accounts [1990] 88.42–43, 92.11–13 Accounts [1991] 95.10–13 Accounts [1992] 98.6–7 Accounts [1994] 101.18–19 Accounts [2000] 125.11 Ackrill, Marion 123.30 Ackroyd, Norman 132.19, 19 Adam, Susan 93.31 Adie, Don, sub-ctee member [1994-] 101.20 Adult education centres 93.5 Advertising 88.8, 127.33–35, 129.29, 132.40 Advisory Committee for Scheme of Management 85.3, 20, 87.26, 88.5–6, 12, 90.8, 92.14–17, 94.35–38, 97.29–39, 98.8–9, 99.18–20, 102.32, 114.5–6, 120.8–11, 32, 130.13–14, 134.11–12, 145.13, 165.3 Agent Zigzag, Ben MacIntyre 159.30–31 AGM [1990] 88.9–11, 89.6 AGM [1991] 90.9, 91.2, 5 AGM [1992] 94.5, 95.6–13 AGM [1993] 97.4, 98.6–7 AGM [1994] 100.5, 101.16–19 AGM [1995]. 104.3, 105.5–6 AGM [1996] 108.5, 109.6–8 AGM [1997] 112.5 AGM [1998] 116.5, 117.7–10 AGM [1999] 120.5 AGM [2000] 124.9 AGM [2001] 128.5, 130.7–8 AGM [2002] 132.6 AGM [2003] 136.8 AGM [2004] 140.16 AGM [2005] 143.33, 144.3 AGM [2006] 147.33, 148.17 AGM [2007] 152.2, 9 AGM [2008] 156.21 AGM [2009] 160.6 AGM [2010] 164.12 AGM [2011] 168.5 AGM [2012] 172.6 AGM [2013] 176.5 Air Training Corps Squadron 153.6–7 Aircraft -

Early Settlement and Employment in the Colony of Victoria

CHAPTER THREE Early settlement and employment in the Colony of Victoria 3.1 General introduction Although the long and difficult voyage to Australia for the Moidart Highlanders was over, for some individuals, their part in this story was to end relatively quickly after their arrival with death following the rigours of the voyage. 1 For other Household members and succeeding generations, the life journeys continued over many years. The focus of this chapter is the arrival and continuation of their journeys in Australia. The chapter begins by outlining the importance and role played by the discovery of gold in establishing the social and economic contexts awaiting the arrival of the Moidart immigrants in 1852. The Moidart immigrants brought with them badly needed agricultural skills, experience and knowledge associated with the sheep industry at a time when the goldfields had enticed many of the labourers away from their employment on the land. Their arrival 1 Five members of Moidart Households died during the voyage of the ‘Allison’: 2.5; 3.6; 3.8; 8.6; and 8.7 whilst two members died in quarantine following its arrival. They were: Household members; 9.8 and 10.2. See 'Allison', nominal passenger and disposal lists VPRS 7666 Inward Passenger Lists-British ports PROV, North Melbourne Book 9, pp. 10-19. and Quarantine Station Cemetery 1852, Friends of the Quarantine Museum, Nepean Historical Society Inc., 10 November, 2002. 160 as a communal group of immigrants did not necessarily mean that they would remain together in Victoria. Many of the married couples for example, arrived with young children to support and needed to move away from the other Households in order to obtain regular wages and rations rather than opting for the vulnerability and insecurity of the goldfields. -

Travels and Adventures of Marco Polo

Conditions and Terms of Use Copyright © Heritage History 2010 Some rights reserved This text was produced and distributed by Heritage History, an organization dedicated to the preservation of classical juvenile history books, and to the promotion of the works of traditional history authors. The books which Heritage History republishes are in the public domain and are no longer protected by the original copyright. They may therefore be reproduced within the United States without paying a royalty to the author. The text and pictures used to produce this version of the work, however, are the property of Heritage History and are licensed to individual users with some restrictions. These restrictions are imposed for the purpose of protecting the integrity of the work itself, for preventing plagiarism, and for helping to assure that compromised or incomplete versions of the work are not widely disseminated. In order to preserve information regarding the origin of this text, a copyright by the author, and a Heritage History distribution date are included at the foot of every page of text. We request all electronic and printed versions of this text include these markings and that users adhere to the following restrictions. 1) This text may be reproduced for personal or educational purposes as long as the original copyright and Heritage History version number are faithfully reproduced. 2) You may not alter this text or try to pass off all or any part of it as your own work. 3) You may not distribute copies of this text for commercial purposes unless you have the prior written consent of Heritage History. -

Updated Active Rental Owners Report

Active Rental Permits and Owners LOC# DIR LOCATION STREET OWNER NAME OWNER ADDRESS CITY STATE ZIP PHONE # 405 ABBOTSFORD FANG CHENG-SHUN & QING 6 GREEN COURT NEWARK DE 19711 302-456-1107 LIU 406 ABBOTSFORD ZHOU, MIN 406 ABBOTSFORD LANE NEWARK DE 19711 302--23-0639 x0 409 ABBOTSFORD MITSURU, TANAKA 13702 CABELLS MILLS DRIVE CENTREVILLE VA 20120 571-455-8892 28 ACADEMY ENGLISH CREEK LLC 502 BRIER AVENUE WILMINGTON DE 19805 302-354-4365 609 ACADEMY JEFFERSON BARBARA A & 4615 SYLVANUS DRIVE WILMINGTON DE 19803 302-764-1550 COREY S 621 ACADEMY MAXWELL HARRIS & VIVEK 229 E 28TH STREET APT 1D NEW YORK NY 10016 302-438-7234 KHASAT 714 ACADEMY LISA, JAMES P. P.O. BOX 4397 WILMINGTON DE 19807 610-745-5000 728 ACADEMY ZHAO YUQIAN TR 17601 COASTAL HWY, UNIT LEWES DE 19958 302-344-9099 10 5 ADELENE DIXON JAMES W & SCHULKE 5 ADELENE DR NEWARK DE 19711 LISA 932 ALEXANDRIA SPOLJARIC, NENAD 2115 CONCORD PIKE WILMINGTON DE 19803 302-575-1007 943 ALEXANDRIA ZHANG YUBEI & CHEN PO BOX 744 HOCKESSIN DE 19707 302-981-8198 BINTONG 9/28/2020 2:00:12 AM 945 ALEXANDRIA GRIFO, N. & E 52 OKLAHOMA STATE DR. NEWARK DE 19713 955 ALEXANDRIA ESKUCHEN CHRISTOPHER L 4021 GANNET WAY FLAGSTAFF AZ 86004 301-741-3538 & JULIA B 974 ALEXANDRIA LI, DIANQUAN 11 AVIGNON DR NEWARK DE 19702 302-883-7988 6 ALFORD XU PING & LOH BOON HUEI 3 HARVEST LANE HOCKESSIN DE 19707 302-743-3604 H&W 15 ALLISON TRACE GLEN & KIMBERLY A 22 CHRISTIAN LANE CHERRY HILL NJ 08002 856-261-5441 22 ALLISON TEKDEL LLC 602 WITHERS CIRCLE WILMINGTON DE 19810 24 ALLISON CHEN, TIANYI 706 W OAKENEADE DR WILMINGTON DE 19810 352-328-0423 6 ALLISON LONG WANG 107 HALLOWEEN RUN NEWARK DE 19711 302-442-0553 4 AMHERST LUO BOYANG C/O PATTERSON SCHWARTZ HOCKESSIN DE 19707 - MAGGIE MESINGER 19 AMSTEL KAPPA ALPHA ED. -

AS AUEOR .535 As SUBJECT;

1 agar—- ‘. THE JEW IN EKGLIEE LITERATURE AS AUEOR .535 as SUBJECT; A Dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Submitted to the University of Virginia, by Edward E. Calisch, 3.L., LA, Richmond Virgi n1 3., 1908. “Rosanna; #:3de v. CHAPTER III The Pro-Elizabethan Period. h-u1-.:a~4w§\‘vh-nll~hx~t11.\t¥ The first mentioneas of the Jews in Englidh literature struck E the keynote or the tneatment that had been accorded them by so i great a majorityiot English writers that it may almost be called unanimous. This treatment very naturall! reflected the attitude or the xngliuh geople toward their Jewish neighbors. This atti- ude was onsfihst was neither pleasant fer the Jews nor credizsble to England. It use one or cruel injustice,antegonism and dispara- h gement. Fer indeed were the author! who had any kind words for the unhappy 'chosen people”. History. The firtj mention,referred to,is an allusion to 25.2 " them round in Bede'slncclesiastical Historx(iritten in ?31. The reference has neither literary or historical merit. Is is given simply because it is the first,and because it has.the significance,that is-a type. It’has to do with a controversy ’ that hsszraged between British and Banish monks upon the highly importsni question or the manner or cutting the monkish tonsnre and or the heaping of Easter. The Romana,desirous or covering their British brothers with inramy accused them or the crimgzihat once in seven years they concurred with the Jews in the celebration at the Easter festival. -

Schomberg" from Liverpool to Melbourne in 1855

DIARY OF THOMAS ANGOVE Passenger on the Clipper ship "Schomberg" from Liverpool to Melbourne in 1855. Extract from the remains of his Diary. NB. This was the last voyage of the Colonial Clipper, Schomberg. In 1855, the Schomberg, skippered by the tough, courageous and quick-tempered Captain James “Bully” Forbes, set forth to establish a new England-Australia sailing record. When the ship he once described as "the noblest that ever floated on water" was drifting to disaster on the rocks west of Bass Strait, he strangely seemed to lose interest and opted for the latter destination in his famous signal - "Melbourne or Hell In Sixty Days". Why we do not know. (From BHP "History of the Bass Strait" Series.) - - - One of the men is much elevated by being made President of the Mess and he does all the dirty work such as clean knives and forks, empty the slops for the ladies, etc. and this he does with pleasure to be called "Mr President". The other, the filibuster of the lot, has been exposed to the destroying hand of time for his hair, which was once a fine carroty colour has flown from the top of his head and has reappeared on each side of his face and chin in abundance which puts one in mind of a Southcotte. The other is half-woman and does not figure so high as the former. The weather is truly delightful with a nice breeze. We are in the Trade Winds and tomorrow we hope to be in the Tropics. Our latitude today is 25 17`. -

The TRAVELS of MARCO POLO

The TRAVELS of MARCO POLO INTRODUCTION AFTER AN ABSENCE OF twenty-six years, Marco Polo and his father Nicolo and his uncle Maffeo returned from the spectacular court of Kublai Khan to their old home in Venice. Their clothes were coarse and tattered; the bun dles that they carried were bound in Eastern cloths and their bronzed faces bore evi dence of great hardships, long endurance, and suffering. They had almost forgotten their native tongue. Their aspect seemed foreign and their ac Copyright 1926 by Boni & Liveright, Inc. cent and entire manner bore the strange stamp of the Tartar. Copyright renewed 1953 by Manuel Komroff During these twenty-six years Venice, too, had changed and Copyright 1930 by Horace Liveright, Inc. the travellers had difficulty in finding their old residence. But here at last as they entered the courtyard they were All rights reserved back home. Back from the Deserts of Persia, back from Printed in the United States of America Manufacturing by the Maple-Vail Book Manufacturing Group the lofty steeps of Pamir, from mysterious Tibet, from the dazzling court of Kublai Khan, from China, Mongolia, Burma, Siam, Sumatra, Java; back from Ceylon, where For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write Adam has his tomb, and back from India, the land of myth to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY and marvels. But the dogs of Venice barked as the travellers 10110 knocked on the door of their old home. The Polos had long been thought dead, and the distant Hardcover ISBN 0-87140-657-8 relatives who occupied the house refused admittance to the Paperback ISBN 0-393-97968-7 three shabby and suspicious looking gentlemen. -

William Duthie Jnr. &

2021 – v1 William Duthie jnr. & Co., Shipbuilders, UPPER DOCK, ABERDEEN, 1856 TO 1870. INCLUDES INFORMATION ON DUTHIE & COCHAR, SHIPBUILDERS, MONTROSE 1854 TO 1856. STANLEY BRUCE William Duthie Jnr. & Co., Shipbuilders, Upper Dock, Aberdeen, 1856 to 1870. Stanley Bruce, 2021-v1 . Due to the age of the photographs, drawings and paintings in this book they are all considered to be out of copyright, however where the photographer, artist or source of the item is known it has been stated directly below it. For any stated as ‘Unknown’ I would be very happy for you to get in touch if you know the artist or photographer. Cover photograph – The 3-masted ship 'Alexander Duthie' moored at Gravesend, U.K., 1875. (Photographer unknown, from the A. D. Edwardes Collection, courtesy of the State Library of South Australia, Ref: PRG 1373/3/3). This book has been published on an entirely non-profit basis and made available to all free of charge as a pdf. The aim of the book is to make the history of vessels built by William Duthie Jnr. & Co. available to a wider audience. There is much available on the internet, especially on www.aberdeenships.com, but unfortunately what’s currently available is scattered and doesn’t give the full picture. If you have any comments regarding this book, or any further information, especially photographs or paintings of vessels where I have none. It would be historically good to show at least one for each vessel, and since this is an electronic edition it will be possible to update and include any new information.