Stevenson, Conrad and the Proto-Modernist Novel Eric Massie

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Met 25% Korting Voor NVM Leden WIJZE VAN BESTELLEN ORDERING INFORMATION BESTELLUNGEN MACHEN

Tekeningen voor Scheepsmodelbouw NEDERLANDSE VERENIGING van MODELBOUWERS Met 25% korting voor NVM leden WIJZE VAN BESTELLEN ORDERING INFORMATION BESTELLUNGEN MACHEN Voor Nederland en landen in de Eurozone: A. Within the Netherlands and the Euro- A. Innerhalb der Euro-Zone bevorzugen A. Als u internet heeft via de webwinkel zone: wir Bestellungen mittels der Webshop auf op www.modelbouwtekeningen.nl Preferably by using our web shop on www.modelbouwtekeningen.nl www.modelbouwtekeningen.nl Folgen Sie die Anweisungen in der Na het plaatsen van uw bestelling kunt u Payments can be made by “Ideal”, Creditcard Konfirmations-Email für Ihre Bezahlung. betalen via Ideal, met een creditcard (Visa of (Visa or Mastercard) or banktransfer. Mastercard) of per bankoverschrijving. In the latter case follow the instructions in B. Falls Sie kein Internet haben oder In het laatste geval volgt u de the confirmation email. Schwierigkeiten mit die Sprache der Web- betaalaanwijzingen in de bevestigingsemail Shop Schreiben Sie Ihre Bestellung an die u ontvangt. B. When using the web shop is not possible due to language problems, or when you do Modelbouwtekeningen.nl B. Als u geen internet heeft schrijft of belt u not have internet: Anthonie Fokkerstraat 2 naar: Write a letter with your order to: 3772MR Barneveld Niederland Modelbouwtekeningen.nl Modelbouwtekeningen.nl Anthonie Fokkerstraat 2 Anthonie Fokkerstraat 2 Zugleich Überweisen Sie das richtige Betrag 3772MR Barneveld 3772MR Barneveld zusätzlich € 7,50 Porto ins Ausland in unsere Tel: 0342400279. The Netherlands. Konto an Modelbouw Media Primair: IBAN: NL70 RABO 0187 4893 19 Gelijkertijd maakt u het juiste bedrag over op And make your payment including a postal BIC: RABONL2U Beim Überweisung de volgende rekening ten name van surcharge of € 7,50 (only for orders outside nennen Sie Ihr Schreiben. -

Arbon, Anthony Lyle PRG 1190/11 Special List ______

___________________________________________________________________ Arbon, Anthony Lyle PRG 1190/11 Special List ___________________________________________________________________ Outsize illustrations of ships 750 illustrations from published sources. These illustrations are not duplicated in the Arbon-Le Maiste collection. Sources include newspaper cuttings and centre-spreads from periodicals, brochures, calendar pages, posters, sketches, plans, prints, and other reproductions of artworks. Most are in colour. Please note the estimated date ranges relate to the ships illustrated, not year of publication. See Series 11/14 for Combined select index to Series 11 arranged alphabetically by ships name. REQUESTING ITEMS: Please provide both ships name and full location details. Unnumbered illustrations are filed in alphabetical order under the name of the first ship mentioned in the caption. ___________________________________________________________________ 1. Illustrations of sailing ships. c1780-. 230 illustrations. Arranged alphabetically by name of ship. 2. Illustrations mainly of ocean going motor powered ships. Excludes navy vessels (see Series 3,4 & 5) c1852- 150 illustrations. Merchant shipping, including steamships, passenger liners, cargo vessels, tankers, container ships etc. Includes a few river steamers and paddleboats. Arranged alphabetically by name of ship. 3. Illustrations of Australian warships. c1928- 21 illustrations Arranged alphabetically by name of ship. 4. Australian general naval illustrations, including warship badges, -

T-Fif OFIENTAW CAFITAIN PALMER

t-fif OFIENTAW CAFITAIN PALMER Thri5tina5 (4Jit• • Nineteen, hundred and twent-9 four eventy-four years ago today, the clipper ship "Oriental" lay in London harbor, %' the pride of American seamen and the envy of the English. And well they might be proud for she was the foremost example of her race, the fleetest type of ship then known. It was the introduction of new methods of travel— steam navigation and the railroad—that brought about her retirement, and not the superiority of others of her kind. Captain Palmer never was out of date. We owe it to ourselves and our times to be useful according to our talents, and to abandon old ways for better, when better ways are found. Let us so resolve. 1 t41 OKIErAL CAFTAN FALAEN ACKNOWLEDGMENT Sources from which information for this book- let were obtained: Mrs. Richard Fanning Loper of Stonington, Connecticut, Captain Palmer's Niece. National Geographic Magazine, March, 1912_ Major-General A. W. Greely Stonington Antarctic Explorers, Edwin S. Balch The Heritage of Tyre, William Brown Meloney The Clipper Ship Era, Arthur Hamilton Clark Captain Nathaniel Brown Palmer, John R. Spears OR centuries the rich trade goods of India—gold, ivory and rubies, spices, perfumes, silks, light as gossamer, linen and finespun cotton cloths, the wools of Cashmere—have been sought by the eager markets of the world. Long caravans of camels plodded across the plains and deserts and through the mountain passes of Asia Minor to the peoples of the Med- iterranean. And we see three mounted wise men carrying the rich tribute of the Orient to a manger in Bethlehem. -

James Curtis and Spiritualism in Nineteenth-Century Ballarat

James Curtis and Spiritualism in Nineteenth-Century Ballarat Greg Young This thesis is submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Faculty of Education and Arts Federation University University Drive, Mount Helen Ballarat 3353 Victoria, Australia STATEMENT OF AUTHORSHIP Except where explicit reference is made in the text this thesis contains no material published elsewhere or extracted in whole or in part from a thesis by which I have qualified for or been awarded another degree of diploma. No other person’s work has been relied upon or used without due acknowledgement in the main text and bibliography. Signed (Applicant): Date: Signed (Supervisor): Date: When the intellectual and spiritual history of the nineteenth century comes to be written, a highly interesting chapter in it will be that which records the origin, growth, decline, and disappearance of the delusion of spiritualism. —Australasian Saturday 25 October 1879 Acknowledgements I am greatly indebted to my University of Ballarat (now Federation University) supervisors Dr Anne Beggs Sunter, Dr Jill Blee, and Dr David Waldron for their encouragement, advice, and criticism. It is also a pleasure to acknowledge a large debt of gratitude to Professor Tony Milner and Professor John Powers, both of the Australian National University, for their generous support. This project began in the Heritage Library of the Ballaarat Mechanics’ Institute; I am grateful to the BMI for its friendly help. Dedication To Anne, Peter, Charlotte, and my teacher Dr Rafe de Crespigny. Abstract This thesis is about the origins, growth, and decline of spiritualism in nine- teenth-century Ballarat. -

The Horan Family Diaspora Since Leaving Ireland 191 Years Ago

A Genealogical Report on the Descendants of Michael Horan and Mary Minnock by A.L. McDevitt Introduction The purpose of this report is to identify the descendants of Michael Horan and Mary Minnock While few Horans live in the original settlement locations, there are still many people from the surrounding areas of Caledon, and Simcoe County, Ontario who have Horan blood. Though heavily weigh toward information on the Albion Township Horans, (the descendants of William Horan and Honorah Shore), I'm including more on the other branches as information comes in. That is the descendants of the Horans that moved to Grey County, Ontario and from there to Michigan and Wisconsin and Montana. I also have some information on the Horans that moved to Western Canada. This report was done using Family Tree Maker 2012. The Genealogical sites I used the most were Ancestry.ca, Family Search.com and Automatic Genealogy. While gathering information for this report I became aware of the importance of getting this family's story written down while there were still people around who had a connection with the past. In the course of researching, I became aware of some differences in the original settlement stories. I am including these alternate versions of events in this report, though I may be personally skeptical of the validity of some of the facts presented. All families have myths. I feel the dates presented in the Land Petitions of Mary Minnock and the baptisms in the County Offaly, Ireland, Rahan Parish registers speak for themselves. Though not a professional Genealogist, I have the obligation to not mislead other researchers. -

The Wreck of the USS ESSEX

xMN History Text 55/3 rev.2 8/20/07 11:15 AM Page 94 The USS Essex, 1904, aground on a shoal at Toledo, Ohio MH 55-3 Fall 96.pdf 4 8/20/07 12:25:36 PM xMN History Text 55/3 rev.2 8/20/07 11:15 AM Page 95 THE WRECK OF THE • USS ESSEX• THE FABRIC OF HISTORY is woven with words and places and with artifacts. While the former provide pattern, the latter give texture. Objects that directly link people to historical events allow us to touch the past. Some are very personal connections between indi- viduals and their ancestors. Others are the touch- stones of our collective memory. Buried in the sand of Lake Superior is the USS ESSEX, an artifact of the nation’s maritime past. A mid- nineteenth-century sloop of war designed by one of America’s foremost naval architects, Donald McKay, the ESSEX traveled around the world and ultimately came to rest on Duluth’s Minnesota Point, about as far from the ocean as a vessel can get. The timbers of the SCOTT F. ANFINSON Scott Anfinson is the archaeologist for the Minnesota Historical Society’s State Historic Preservation Office. He received a Master’s degree in anthropology from the University of Nebraska in 1977 and a Ph.D. in anthropology from the University of Minnesota in 1987. Besides directing the Minnesota Shipwreck Initiative, his research interests focus on the American Indian archaeology of southwestern Minnesota and the history of the Minneapolis riverfront. MH 55-3 Fall 96.pdf 5 8/20/07 12:25:37 PM xMN History Text 55/3 rev.2 8/20/07 11:15 AM Page 96 ern part of the state. -

January 1968

JANUARY 1968 River of Ice On a trip to Alaska to take pictures for a Boeing Magazine story ("Gravel Gertie," December issue), staff photographer Ver- non Manion exercised his camera a few times on the flight. He snapped the accompanying photo- graph from an Alaska Airlines Model 727 on its way to arctic Kotzebue. What appears to be a river in the photograph is a moving glacier-solid ice oozing down the mountain in a lava-like flow but infinitely slower. Hear the Wind Blow Enrique B. Santos, editor of The PALiner, em- ployee newspaper of Philippine Air Lines, explained to his readers how PAL had contributed to the an- tique airplane collection of the Smithsonian Institu- tion in 1946. Three unnamed antique aircraft were on display at the Oakland (California) Airport. The Smithsonian had bid for the planes but been turned down by their owners. Came the day when PAL began its first transpacific service, its DC-4 on the apron near the antique airplanes. "Then our pilots fired up the engines," wrote Santos, "increased power to taxi away and blew the three airplanes into pieces on the ramp." The owners were at last willing to sell the airplanes to the Smithsonian-piece by piece. "Thus, in a manner of speaking," concludes Santos, "did PAL make a contribution to the Smithsonian." The Flying Sieve Master Sergeant Stephen N. Garlock, 22nd Air Force detachment at Hickam Air Force Base, Hawaii, was looking at a group of posters commemorating the Air Force's 20th anniversary in September. He saw a picture of the B-17 Thunderbird, a plane on which he flew the Mannheim mission in 1944. -

Old Ships and Ship-Building Days of Medford 1630-1873

OLD SHIPS AND SHIP-BUILDING DAYS OF MEDFORD 1630-1873 By HALL GLEASON WEST MEDFORD, MASS. 1936 -oV Q. co U © O0 •old o 3 § =a « § S5 O T3». Sks? r '■ " ¥ 5 s<3 H " as< -,-S.s« «.,; H u « CxJ S Qm § -°^ fc. u§i G rt I Uh This book was reproduced by the Medford Co-operative Bank. January 1998 Officers Robert H. Surabian, President & CEO Ralph W. Dunham, Executive Vice President Henry T. Sampson, Jr., Senior Vice President Thomas Burke, Senior Vice President Deborah McNeill, Senior Vice President John O’Donnell, Vice President John Line, Vice President Annette Hunt, Vice President Sherry Ambrose, Assistant Vice President Pauline L. Sampson, Marketing & Compliance Officer Patricia lozza, Mortgage Servicing Officer Directors John J. McGlynn, Chairman of the Board Julie Bemardin John A. Hackett Richard M. Kazanjian Dennis Raimo Lorraine P. Silva Robert H. Surabian CONTENTS. Chapter Pagf. I. Early Ships 7 II. 1800-1812 . 10 III. War of 1812 19 IV. 1815-1850 25 V. The Pepper Trade 30 VI. The California Clipper Ship Era . 33 VII. Storms and Shipwrecks . 37 VIII. Development of the American Merchant Vessel 48 IX. Later Clipper Ships 52 X. Medford-Built Vessels . 55 Index 81 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS. Page Clipper Ship Thatcher Magoun Frontispiece Medford Ship-Builders 7 Yankee Privateer 12 Mary Pollock Subtitle from Kipling’s “Derelict *’ 13 Heave to 20 The Squall . 20 A Whaler 21 Little White Brig 21 Little Convoy 28 Head Seas 28 Ship Lucilla 28 Brig Magoun 29 Clipper Ship Ocean Express 32 Ship Paul Jones” 32 Clipper Ship “Phantom” 32 Bark Rebecca Goddard” 33 Clipper Ship Ringleader” 36 Ship Rubicon 36 Ship Bazaar 36 Ship Cashmere 37 Clipper Ship Herald of the Morning” 44 Bark Jones 44 Clipper Ship Sancho Panza 44 Clipper Ship “Shooting Star 45 Ship “Sunbeam” . -

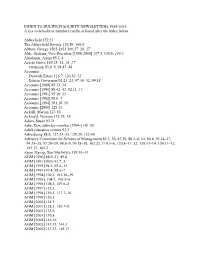

INDEX to DULWICH SOCIETY NEWSLETTERS 1989-2014 a Key to Newsletter Numbers Can Be at Found After the Index Below

INDEX TO DULWICH SOCIETY NEWSLETTERS 1989-2014 A key to newsletter numbers can be at found after the index below. Abbeyfield 152.31 The Abbeyfield Society 119.29, 160.8 Abbott, George 1562-1633 166.27–28, 27 Able, Graham, Vice-President [1998-2000] 117.9, 138.8, 140.3 Abrahams, Adam 85.3–4 Acacia Grove 169.25–31, 26–27 extension 93.8–9, 94.47–48 Accounts Dulwich Estate 116.7, 120.30–32 Estates Governors 92.21–23, 97.30–32, 99.18 Accounts [1989] 85.33–34 Accounts [1990] 88.42–43, 92.11–13 Accounts [1991] 95.10–13 Accounts [1992] 98.6–7 Accounts [1994] 101.18–19 Accounts [2000] 125.11 Ackrill, Marion 123.30 Ackroyd, Norman 132.19, 19 Adam, Susan 93.31 Adie, Don, sub-ctee member [1994-] 101.20 Adult education centres 93.5 Advertising 88.8, 127.33–35, 129.29, 132.40 Advisory Committee for Scheme of Management 85.3, 20, 87.26, 88.5–6, 12, 90.8, 92.14–17, 94.35–38, 97.29–39, 98.8–9, 99.18–20, 102.32, 114.5–6, 120.8–11, 32, 130.13–14, 134.11–12, 145.13, 165.3 Agent Zigzag, Ben MacIntyre 159.30–31 AGM [1990] 88.9–11, 89.6 AGM [1991] 90.9, 91.2, 5 AGM [1992] 94.5, 95.6–13 AGM [1993] 97.4, 98.6–7 AGM [1994] 100.5, 101.16–19 AGM [1995]. 104.3, 105.5–6 AGM [1996] 108.5, 109.6–8 AGM [1997] 112.5 AGM [1998] 116.5, 117.7–10 AGM [1999] 120.5 AGM [2000] 124.9 AGM [2001] 128.5, 130.7–8 AGM [2002] 132.6 AGM [2003] 136.8 AGM [2004] 140.16 AGM [2005] 143.33, 144.3 AGM [2006] 147.33, 148.17 AGM [2007] 152.2, 9 AGM [2008] 156.21 AGM [2009] 160.6 AGM [2010] 164.12 AGM [2011] 168.5 AGM [2012] 172.6 AGM [2013] 176.5 Air Training Corps Squadron 153.6–7 Aircraft -

The Making of the City Marketing of Amsterdam I Amsterdam Toekomst, Over De Richting Die Amsterdam Area Uitmoet, Proud Flag on the Ship

The Making of... the city marketing of Amsterdam Het ontstaan van de city marketing van Amsterdam I amsterdam Het ontstaan van de city marketing van Amsterdam 1 Inhoudsopgave contents Voorwoord Foreword 5 1 Inleiding Introduction 9 2 Het marketing concept The marketing concept 13 2.1 De plaats van Amsterdam in de wereld Amsterdam’s place in the world 14 2.2 Uitgaan van de kracht van Amsterdam Starting from the strengths of Amsterdam 14 2.2.1 Conceptuele systematiek Creating the Concept 15 2.2.2 Analyse: de sterkten, zwakten en kansen Analysis: strengths, weaknesses and opportunities 17 2.3 Doelgroepen Target groups 20 2.3.1 Doelstellingen van city marketing Objectives of city marketing 23 2.4 Kern van het nieuwe concept Core of the new concept 25 3 Naar een nieuwe organisatie van de city marketing Towards a new organisation for city marketing 27 3.1 Uitgangspunt voor onderzoek van de organisatie Starting point for study of the organisation 28 3.2 Het functioneren van de bestaande organisaties Functioning of existing organisations 28 3.3 Een nieuwe organisatie voor citymarketing – de kop er bovenop A new umbrella organisation for city marketing 30 3.4 Uitwerking van verantwoordelijkheden en taken Responsibilities and tasks 32 3.4.1 Rollen gemeente Roles of the City of Amsterdam 33 3.4.2 Rollen overige partners Roles of other partners 34 4 City marketing en beleid City marketing and policy 37 4.1 De impulsen The impulses 39 4.2 Focus in regulier beleid: parelprojecten Focus on normal policy: ‘pearl’ projects 39 4.3 Festival- en evenementenbeleid -

Telling Pacific Lives

TELLING PACIFIC LIVES PRISMS OF PROCESS TELLING PACIFIC LIVES PRISMS OF PROCESS Brij V. Lal & Vicki Luker Editors Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/tpl_citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Telling Pacific lives : prisms of process / editors, Vicki Luker ; Brij V. Lal. ISBN: 9781921313813 (pbk.) 9781921313820 (pdf) Notes: Includes index. Subjects: Islands of the Pacific--Biography. Islands of the Pacific--Anecdotes. Islands of the Pacific--Civilization. Islands of the Pacific--Social life and customs. Other Authors/Contributors: Luker, Vicki. Lal, Brij. Dewey Number: 990.0099 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Teresa Prowse Cover image: Choris, Louis, 1795-1828. Iles Radak [picture] [Paris : s.n., [1827] 1 print : lithograph, hand col.; 20.5 x 26 cm. nla.pic-an10412525 National Library of Australia Printed by University Printing Services, ANU This edition © 2008 ANU E Press Table of Contents Preface vii 1. Telling Pacic Lives: From Archetype to Icon, Niel Gunson 1 2. The Kila Wari Stories: Framing a Life and Preserving a Cosmology, Deborah Van Heekeren 15 3. From ‘My Story’ to ‘The Story of Myself’—Colonial Transformations of Personal Narratives among the Motu-Koita of Papua New Guinea, Michael Goddard 35 4. Mobility, Modernisation and Agency: The Life Story of John Kikang from Papua New Guinea, Wolfgang Kempf 51 5. -

Sailors Guyana Get Away to C Ariben

C A R I B B E A N On-line C MPASS JULY 2011 NO. 190 The Caribbean’s Monthly Look at Sea & Shore SAILORS GET AWAY TO GUYANA See story on page 23 KAY E. GILMOUR JULY 2011 CARIBBEAN COMPASS PAGE 2 DEPARTMENTS Info & Updates ......................4 The Caribbean Sky ...............34 Business Briefs .......................7 Book Reviews ........................35 Eco-News .............................. 11 Cooking with Cruisers ..........36 Regatta News........................ 12 Readers’ Forum .....................37 Meridian Passage .................22 What’s on My Mind ............... 40 Sailor’s Horoscope ................ 32 Calendar of Events ...............41 The Caribbean’s Monthly Look at Sea & Shore Cruising Crossword ............... 32 Caribbean Market Place .....42 www.caribbeancompass.com Island Poets ...........................33 Classified Ads ....................... 46 Dolly’s Deep Secrets ............33 Advertisers’ Index .................46 JULY 2011 • NUMBER 190 Caribbean Compass is published monthly by Martinique: Ad Sales & Distribution - Isabelle Prado Compass Publishing Ltd., P.O. Box 175 BQ, Tel: (0596) 596 68 69 71, Mob: + 596 (0) 696 93 26 38 SEWLAL Bequia, St. Vincent and the Grenadines. [email protected] Tel: (784) 457-3409, Fax: (784) 457-3410 Puerto Rico: Ad Sales - Ellen Birrell [email protected] 787-504-5163, [email protected] HARNEY www.caribbeancompass.com Distribution - Sunbay Marina, Fajardo Olga Diaz de Peréz Editor...........................................Sally Erdle Tel: (787) 863 0313