Historic Forfar, the Archaeological Implications of Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Line of March

NYC TARTAN DAY PARADE - April 9, 2016 LINE OF MARCH FIRST DIVISION: West 44th Street from 6th Avenue to 5th Avenue Section 1: Forms from corner of 6th Avenue East to 59 West 44th Street 1. NYC Police Department Mounted Unit (forms on 6th Avenue above W. 45th Street) 2. U.S. Military Academy (West Point) Pipes and Drums 3. Grand Marshal Banner 4. Grand Marshal Sam Heughan (with family/friends ) 5. St. Andrew’s Color Guard 6. NTDNYC Banner 7. Edinburgh Academy Pipe and Drum Band 8. National Tartan Day New York Parade Committee 9. BARBOUR 10. U.S. Naval Academy (Annapolis) Pipes and Drums 11. Scottish American Military Society Color Guard 12. VIPs: Hon. Tricia Marwick, MSP; Fergus Cochrane 13. Scottish Parliament/Politicians/U.S. Politicians 14. Visit Scotland Section 2: Forms from 59 West 44th Street to 37 West 44th Street 1. Mt. Kisco Scottish Pipes and Drums 2. St. Andrew’s Society of New York 3. New York Caledonian Club Pipe Band 4. New York Caledonian Club 5. New York Metro Pipe Band 6. American Scottish Foundation 7. Tri-County Pipes and Drums 8. Clan Fraser 9. Clan Ross 10. St. Andrew’s Society; City of Albany 11. Pipes and Drums of the Atlantic Watch 12. Daughters of Scotia - 1 - Section 2: Continued 13. Daughters of the British Empire 14. Clan Abernathy of Richmond 15. CARNEGIE HALL Section 3: Forms from 37 West 44th Street to 27 West 44th Street 1. NYC Police Department Marching Band 2. Clan Malcolm/Macallum 3. Clan MacIneirghe 4. Long Island Curling Club 5. -

Colonel Arren Calvin Buchanan, Jr. INTERVIEWER

INSTITUTE OF TEXAN CULTURES ORAL HISTORY PROGRAM INTERVIEW WITH: Colonel Arren Calvin Buchanan, Jr. INTERVIEWER: Jim Sweeney DATE: January 19, 1985 PLACE: Air Force Village, San Antonio, Texas TITLE: The Scots in Texas Clan Buchanan (Society in America, Inc.) [Music is playing at the beginning of the tape: bagpipes.) S: Colonel Buchanan, I understand you are of Scottish descent and also a third generation Texan. Now that's quite a combination. Would you mind telling us a little bit about that? B: Yes, I'll be happy to, Jim. My great-grandfather, James Buchanan of Alabama, came with Stephen F. Austin's fifth colony, 1835, to what became Washington-on-the-Brazos. He was a farmer and built a log cabin down in Montgomery County. And he then was drafted into the Texas Army with General Sam Houston; and was subsequently killed in the Battle of the Alamo. And you will find his name, James Buchanan, of Alabama, on the north wall of the Alamo. His widow was given a grant of l a nd in 1844 by the Republic of Texas; and the grant was signed by Presiden t Sam Houston. My father was born on this grant of land, below Caldwe ll, in 1862, the son of James Houston Buchanan, BUCHANAN 2 B: the grandson of James Buchanan. So, therefore, we have roots that go back into early Texas history. Many of the Stephen F. Austin's colonists, as you see this was the fifth colony, were Scottish that carne across from the Ea st Coast. Another important colony which should be mentioned is the Sterling C. -

The Dewars of St. Fillan

History of the Clan Macnab part five: The Dewars of St. Fillan The following articles on the Dewar Sept of the Clan Macnab were taken from several sources. No attempt has been made to consolidate the articles; instead they are presented as in the original source, which is given at the beginning of each section. Hence there will be some duplication of material. David Rorer Dewar means roughly “custodian” and is derived from the Gallic “Deoradh,” a word originally meaning “stranger” or “wanderer,” probably because the person so named carried St. Fillan’s relics far a field for special purposes. Later, the meaning of the word altered to “custodian.” The relics they guarded were the Quigrich (Pastoral staff); the Bernane (chapel Bell), the Fergy (possibly St. Fillan’s portable alter), the Mayne (St. Fillan’s arm bone), the Maser (St. Fillan’s manuscript). There were, of course other Dewars than the Dewars of St. Fillan and the name today is most familiar as that of a blended scotch whisky produced by John Dewar and Sons Ltd St. Fillan is mentioned in the Encyclopedia Britannica, 14th edition of 1926, as follows: Fillan, Saint or Faelan, the name of two Scottish saints, of Irish origin, whose lives are of a legendary character. The St. Fillan whose feast is kept on June 20 had churches dedicated to him at Ballyheyland, Queen’s county, Ireland, and at Loch Earn, Perthshire (see map of Glen Dochart). The other, who is commerated on January 9, was specially venerated at Cluain Mavscua in County Westmeath, Ireland. Also beginning about the 8th or 9th century at Strathfillan, Perthshire, Scotland, where there was an ancient monastery dedicated to him. -

Dryburgh, Mr A

Title: Mr Forename: Archie Surname: Dryburgh Representing: Organisation Organisation (if applicable): Annandale East and Eskdale Ward Councillor for Dumfries and Galloway Council Email: What additional details do you want to keep confidential?: No If you want part of your response kept confidential, which parts?: Ofcom may publish a response summary: Yes I confirm that I have read the declaration: Yes Additional comments: Question 1: Do you agree that the existing obligations on Channel 3 and Channel 5 licensees in respect of national and international news and current affairs, original productions, and Out of London productions should be maintained at their current levels? If not, what levels do you consider appropriate, and why?: No, belive that border area should have some more coverage due to the region in which itv border originally covered Question 2: Do you agree with ITV?s proposals for changes to its regional news arrangements in England, including an increase in the number of news regions in order to provide a more localised service, coupled with a reduction in overall news minutage? : Yes Question 3: Do you agree with UTV?s proposal for non-news obligations should be reduced to 90 minutes a week? If not, what alternative would you propose and why?: n/a Question 4: Do you agree with the proposals by STV to maintain overall minutage for regional content in the northern and central licence areas of Scotland at 5 hours 30 minutes a week, as detailed in Annex 3? If not, what alternative would you propose, and why? : n/a Question -

The River Tay - Its Silvery Waters Forever Linked to the Picts and Scots of Clan Macnaughton

THE RIVER TAY - ITS SILVERY WATERS FOREVER LINKED TO THE PICTS AND SCOTS OF CLAN MACNAUGHTON By James Macnaughton On a fine spring day back in the 1980’s three figures trudged steadily up the long climb from Glen Lochy towards their goal, the majestic peak of Ben Lui (3,708 ft.) The final arête, still deep in snow, became much more interesting as it narrowed with an overhanging cornice. Far below to the West could be seen the former Clan Macnaughton lands of Glen Fyne and Glen Shira and the two big Lochs - Fyne and Awe, the sites of Fraoch Eilean and Dunderave Castle. Pointing this out, James the father commented to his teenage sons Patrick and James, that maybe as they got older the history of the Clan would interest them as much as it did him. He told them that the land to the West was called Dalriada in ancient times, the Kingdom settled by the Scots from Ireland around 500AD, and that stretching to the East, beyond the impressively precipitous Eastern corrie of Ben Lui, was Breadalbane - or upland of Alba - part of the home of the Picts, four of whose Kings had been called Nechtan, and thus were our ancestors as Sons of Nechtan (Macnaughton). Although admiring the spectacular views, the lads were much more keen to reach the summit cairn and to stop for a sandwich and some hot coffee. Keeping his thoughts to himself to avoid boring the youngsters, and smiling as they yelled “Fraoch Eilean”! while hurtling down the scree slopes (at least they remembered something of the Clan history!), Macnaughton senior gazed down to the source of the mighty River Tay, Scotland’s biggest river, and, as he descended the mountain at a more measured pace than his sons, his thoughts turned to a consideration of the massive influence this ancient river must have had on all those who travelled along it or lived beside it over the millennia. -

The Norse Influence on Celtic Scotland Published by James Maclehose and Sons, Glasgow

i^ttiin •••7 * tuwn 1 1 ,1 vir tiiTiv^Vv5*^M òlo^l^!^^ '^- - /f^K$ , yt A"-^^^^- /^AO. "-'no.-' iiuUcotettt>tnc -DOcholiiunc THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND PUBLISHED BY JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS, GLASGOW, inblishcre to the anibersitg. MACMILLAN AND CO., LTD., LONDON. New York, • • The Macmillan Co. Toronto, • - • The Mactnillan Co. of Canada. London, • . - Simpkin, Hamilton and Co. Cambridse, • Bowes and Bowes. Edinburgh, • • Douglas and Foults. Sydney, • • Angus and Robertson. THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND BY GEORGE HENDERSON M.A. (Edin.), B.Litt. (Jesus Coll., Oxon.), Ph.D. (Vienna) KELLY-MACCALLUM LECTURER IN CELTIC, UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW EXAMINER IN SCOTTISH GADHELIC, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON GLASGOW JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS PUBLISHERS TO THE UNIVERSITY I9IO Is buaine focal no toic an t-saoghail. A word is 7nore lasting than the world's wealth. ' ' Gadhelic Proverb. Lochlannaich is ànnuinn iad. Norsemen and heroes they. ' Book of the Dean of Lismore. Lochlannaich thi'eun Toiseach bhiir sgéil Sliochd solta ofrettmh Mhamiis. Of Norsemen bold Of doughty mould Your line of oldfrom Magnus. '' AIairi inghean Alasdair Ruaidh. PREFACE Since ever dwellers on the Continent were first able to navigate the ocean, the isles of Great Britain and Ireland must have been objects which excited their supreme interest. To this we owe in part the com- ing of our own early ancestors to these isles. But while we have histories which inform us of the several historic invasions, they all seem to me to belittle far too much the influence of the Norse Invasions in particular. This error I would fain correct, so far as regards Celtic Scotland. -

A Walking Guide to Inchcailloch Innis Cailleach Leabhar-I�Il Do Luchd-Coiseachd

A walking guide to Inchcailloch Innis Cailleach leabhar-iil do luchd-coiseachd Please give this leaflet back to the visitor centre when you have finished with it! A jewel in Loch Lomond Seud ann an Loch Laomainn lochlomond-trossachs.org Welcome to Inchcailloch Discover how dramatic natural forces and The Summit Path is more strenuous with a steep years of human use have combined to climb to the top of the island. Here you’ll find out how dramatic forces of nature have sculpted the create an island of remarkable diversity. island and created lots of different homes for plants There are two walking routes and animals. on the island – the Low Path You can visit the island all year and the Summit Path. They round weather permitting. can be enjoyed separately or If you don’t have your own boat, together. Stopping points you can be taken there from are marked with numbered Balmaha or Luss by one of the posts on each path which ferry services. More information relate to the sections in this is on the Inchcailloch section Walking Guide. The points run of our website. consecutively from one path to the other. Each path takes 30- The wooded island of Inchcailloch 45 minutes, but take your time is a gem in the loch and part of and enjoy the view. Loch Lomond National Nature Reserve. Loch Lomond & The The Low Path is a gentle Trossachs National Park Authority woodland walk with a few manages the island for people slopes. At first sight the woods and nature. -

Tigh Sona, 18 Dunhallin, Waternish, Isle of Skye, IV55 8GH

The Isle of Skye Estate Agency Portree Office: [email protected] The Isle of Skye Estate Agency 01478 612 683 Kyle Office: [email protected] www.iosea.co.uk 01599 534 555 Tigh Sona, 18 Dunhallin, Waternish, Isle of Skye, IV55 8GH. Offers Over £325,000 Elevated position 4.5 Acre Owner Occupied Croft (To Be Confirmed By Title) Stone Byre Prime for Conversion 3 Bedrooms Subdivided into Two Self Contained Units Sea Views Description: Tigh Sona is a detached property that is subdivided into two self contained units occupying an elevated position in the picturesque crofting township of Dunhallin, Waternish. Set within a 4.5 acre owner occupied croft the property boasts far reaching sea views over The Minch out towards The Outer Hebrides beyond. Tigh Sona & Island View offer purchasers a unique opportunity to purchase a detached 1 & 1/2 storey three bedroom property with the potential for a variety of uses. The property is currently subdivided into two self contained holiday letting units which are connected via an internal connecting door. Tigh Sona is set out over two floors and comprises of entrance hallway, Inner hall and open plan lounge/ kitchen diner on the ground floor with two bedrooms and family bathroom located on the first floor. Island View is set out over one level and comprises of: kitchen, sitting room, hall and en-suite bedroom. The property also benefits from UPVC double glazing throughout, electric storage heating, multi fuel stove and open fire. Externally, the garden grounds are mainly laid to lawn with a large gravel parking area to the front of the property. -

Arbon, Anthony Lyle PRG 1190/11 Special List ______

___________________________________________________________________ Arbon, Anthony Lyle PRG 1190/11 Special List ___________________________________________________________________ Outsize illustrations of ships 750 illustrations from published sources. These illustrations are not duplicated in the Arbon-Le Maiste collection. Sources include newspaper cuttings and centre-spreads from periodicals, brochures, calendar pages, posters, sketches, plans, prints, and other reproductions of artworks. Most are in colour. Please note the estimated date ranges relate to the ships illustrated, not year of publication. See Series 11/14 for Combined select index to Series 11 arranged alphabetically by ships name. REQUESTING ITEMS: Please provide both ships name and full location details. Unnumbered illustrations are filed in alphabetical order under the name of the first ship mentioned in the caption. ___________________________________________________________________ 1. Illustrations of sailing ships. c1780-. 230 illustrations. Arranged alphabetically by name of ship. 2. Illustrations mainly of ocean going motor powered ships. Excludes navy vessels (see Series 3,4 & 5) c1852- 150 illustrations. Merchant shipping, including steamships, passenger liners, cargo vessels, tankers, container ships etc. Includes a few river steamers and paddleboats. Arranged alphabetically by name of ship. 3. Illustrations of Australian warships. c1928- 21 illustrations Arranged alphabetically by name of ship. 4. Australian general naval illustrations, including warship badges, -

Boisdale of Canary Wharf Whisky Bible

BOISDALE Boisdale of Canary Wharf Whisky Bible 1 All spirits are sold in measures of 25ml or multiples thereof. All prices listed are for a large measure of 50ml. Should you require a 25ml measure, please ask. All whiskies are subject to availability. 1. Springbank 10yr 19. Old Pulteney 12yr 37. Ardbeg Corryvreckan 55. Longmorn 16yr 2. Highland Park 12yr 20. Aberfeldy 12yr 38. Smokehead 56. Glenrothes Select Reserve 3. Bowmore 12yr 21. Blair Athol 12yr 39. Lagavulin 16yr 57. Glenfiddich 15yr Solera 4. Oban 14yr 22. Royal Lochnagar 12yr 40. Laphroaig Quarter Cask 58. Glenfarclas 10yr 5. Cragganmore 12yr 23. Talisker 10yr 41. Laphroaig 10yr 59. Ben Nevis 12yr 6. Fettercairn (Old) 10yr 24. Laphroaig 15yr 42. Octomore 7.1 60. Highland Park 18yr 7. Benromach 10yr 25. Benriach Curiositas 10yr 43. Tomintoul 16yr 61. Glenfarclas 40yr 105 8. Ardmore Traditional 26. Caol Ila 12yr 44. Glengoyne 10yr 62. Macallan 10yr Sherry Oak 9. Connemara Peated 27. Port Charlotte 2008 45. Cardhu 12yr 63. Glendronach 12yr 10. St. George’s Chapter 9 28. Loch Lomond 12yr 46. An Cnoc 16yr 64. Balvenie 12yr DoubleWood 11. Isle of Jura 10yr 29. Speyburn 10yr 47. Glenkinchie 12yr 65. Aberlour 10yr 12. Glen Garioch 21yr 30. Balblair 1997 48. Macallan 12yr Fine Oak 66. Glengoyne 12yr 13. Tobermory 10yr 31. Bruichladdie Classic 49. Glenfiddich 12yr 67. Penderyn Madeira 14. Dalwhinnie 15yr Laddie 50. Bushmills 10yr 68. Glen Moray 12yr 15. Glenmorangie Original 32. Tullibardine 223 51. Tomatin 12yr 69. Glen Grant 10yr 16. Bunnahabhain 12yr 33. Tomatin 18yr 52. Glenlivet 12yr 70. -

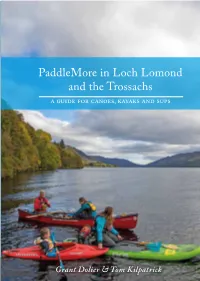

Paddlemore in Loch Lomond and the Trossachs a Guide for Canoes, Kayaks and Sups Paddlemore in Loch Lomond and the Trossachs a Guide for Canoes, Kayaks and Sups

PaddleMore in LochTrossachs PaddleMore Lomond and the PaddleMore in Loch Lomond and the Trossachs a guide for canoes, kayaks and sups PaddleMore in Loch Lomond and the Trossachs a guide for canoes, kayaks and sups Whether you want hardcore white water, multi-day touring Kilpatrick Tom & Dolier Grant trips or a relaxing afternoon exploring sheltered water with your family, you’ll find all that and much more in this book. Loch Lomond & The Trossachs National Park is long estab- lished as a playground for paddlers and attracts visitors from all over the world. Loch Lomond itself has over eighty kilometres of shoreline to explore, but there is so much more to the park. The twenty-two navigable lochs range from the vast sea lochs around Loch Long to small inland Loch Lomond bodies such as Loch Chon. & the Trossachs The rivers vary from relaxed meandering waterways like the Balvaig to the steep white water of the River Falloch and 9 781906 095765 everything in between. Cover – Family fun on Loch Earn | PaddleMore Back cover – Chatting to the locals, River Balvaig | PaddleMore Grant Dolier & Tom Kilpatrick Loch an Daimh Loch Tulla Loch Also available from Pesda Press Bridge of Orchy Lyon Loch Etive Loch Tay Killin 21b Tyndrum River Dochart River Loch 21a Fillan Iubhair Loch Awe 20 LOCH LOMOND & Crianlarich Loch Lochearnhead Dochart THE TROSSACHS 19 Loch NATIONAL PARK Earn Loch 5 River Doine 17 River Falloch Loch 32 Voil Balvaig 23 Ardlui 18 Loch Loch Sloy Lubnaig Loch Loch Katrine Arklet 12 Glen Finglas Garbh 3 10 Reservoir Uisge 22 Callander -

The Stirling Battle

The Winter Walks trails have been created to encourage people to get out, explore, and learn more about the unique history of Stirling and how places have changed over time. Along each 1.5 hour trail there are four stops with information on the history of that location, puzzles and activities to complete. BEFORE YOU START - Review the map and make sure you know the route Winter - Take a pen or pencil to record your answers - Check the weather and take appropriate clothing WHILE ON THE WALK - Look out for traffic and other dangers - Use pedestrian crossing when available Walks - Respect guidance on physical distancing and group sizes to keep yourself and others safe The Stirling Battle Solve the puzzles and enter the draw to win fun prizes from local businesses! for kids ENTER THE PRIZE DRAW Mail in your completed activity sheet to: M Jackson, Transport Development Stirling Council Teith House, Stirling, FK7 7QA You can also help us to enhance local places for the future by com- pleting the place survey online. SEE PRIZES AVAILABLE AND SUBMIT SURVEY ONLINE: https://engage.stirling.gov.uk/en-GB/folders/wlcs OR email: [email protected] *Responses to the places surveys will be used to inform the devel- opment of the Walk Cycle Live Stirling. elorer 1. South of the Old Stirling Bridge 2. North of the Old Stirling Bridge 700 years ago, in the 13th century before all the buildings and roads that The English were impatient by the inaction of the Scots, so they started you see around were built, there was just the river, the bridge and some to cross the narrow bridge.