Pogrom Cries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Archives of Poland and Where to Find Online Genealogy Records for Each - Sheet1

The Archives of Poland and where to find Online Genealogy Records for each - Sheet1 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License Archives of Poland Territorial coverage Search theGenBaza ArchivesGenetekaJRI-PolandAGAD Przodek.plGesher Archeion.netGalicia LubgensGenealogyPoznan in the BaSIAProject ArchivesPomGenBaseSzpejankowskisPodlaskaUpper and Digital Szpejenkowski SilesianSilesian Library Genealogical Digital Library Society Central Archives of Historical Records All Poland ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ National Digital Archive All Poland ✓ ✓ Central Archives of Modern Records All Poland ✓ ✓ Podlaskie (primarily), State Archive in Bialystok Masovia ✓ ✓ ✓ The Archives of Poland and where to find Online Genealogy Records for each - Sheet1 Branch in Lomza Podlaskie ✓ ✓ Kuyavian-Pomerania (primarily), Pomerania State Archive in Bydgoszcz and Greater Poland ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Kuyavian-Pomerania (primarily), Greater Branch in Inowrocław Poland ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Silesia (primarily), Świetokrzyskie, Łódz, National Archives in Częstochowa and Opole ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Pomerania (primarily), State Archive in Elbląg with the Warmia-Masuria, Seat in Malbork Kuyavian-Pomerania ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ State Archive in Gdansk Pomerania ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Gdynia Branch Pomerania ✓ ✓ ✓ State Archive in Gorzow Lubusz (primarily), Wielkopolski Greater Poland ✓ ✓ ✓ Greater Poland (primarily), Łódz, State Archive in Kalisz Lower Silesia ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Silesia (primarily), State Archive in Katowice Lesser Poland ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Branch in Bielsko-Biala Silesia ✓ ✓ ✓ Branch in Cieszyn Silesia ✓ ✓ ✓ Branch -

Michalina Tatarkówna-Majkowska Biografia

Uniwersytet Łódzki Wydział Filozoficzno – Historyczny Piotr Ossowski Michalina Tatarkówna-Majkowska Biografia Praca doktorska napisana w Katedrze Historii Polski i Świata po 1945 r. pod kierunkiem prof. nadzw. dr hab. Krzysztofa Lesiakowskiego Łódź 2016 2 SPIS TRE ŚCI Wykaz skrótów……………………………………………………………………......... 5 Wst ęp…………………………………………………………………………………… 9 Rozdział I Robotnicza dola (1908-1945)……………………………………… 22 Rozdział II Pocz ątek kariery politycznej (1945-1953)………………………… 55 1. W Komitecie Dzielnicowym PPR Łód ź Widzew…………. 55 2. W czasach stalinowskich…………………………………... 77 Rozdział III W kr ęgu elity władzy (1953-1955)………………………………... 84 1. Obj ęcie stanowiska I sekretarza KW PZPR w Łodzi……… 84 2. Kierownik polityczny województwa łódzkiego…………… 89 Rozdział IV Burzliwe lata (1955-1957)………………………………………… 109 1. Okoliczno ści awansu na I sekretarza KŁ PZPR…………… 109 2. W obliczu walk frakcyjnych w PZPR……………………... 113 3. Przełom pa ździernikowy po łódzku………………………... 133 4. Sprawdzian wyborczy w styczniu 1957 r………………….. 140 Rozdział V Zwierzchnik łódzkiej organizacji partyjnej (1955-1964)………….. 156 1. Działalno ść na forum Egzekutywy KŁ PZPR……………... 156 2. System nomenklatury i polityka kadrowa………………….. 159 3. Wpływ na funkcjonowanie lokalnego aparatu partyjnego…. 168 4. Udział w ogólnopolskim życiu politycznym………………. 175 5. Posłanka na Sejm…………………………………………... 184 6. Funkcja reprezentacyjna: podró że zagraniczne i przyjmowanie go ści………………………………………. 188 7. Wyró żnienia i odznaczenia………………………………… 192 Rozdział VI Ró żne barwy rz ądzenia Łodzi ą (1955-1964)……………………… 195 1. Wobec problemów mieszka ńców………………………….. 195 2. Laicyzacja i ideologizacja o światy………………………… 200 3. Udział w przebudowie miasta……………………………… 216 4. Kształtowanie życia kulturalnego………………………….. 228 5. Świ ęta i rocznice…………………………………………… 243 3 Rozdział VII Na emeryturze (1964-1986)……………………………………….. 248 1. Odwołanie ze stanowiska I sekretarza KŁ PZPR…………. -

Tokarska-Bakir the Kraków Pogrom the Kraków Pogrom of 11 August

Tokarska-Bakir_The Kraków pogrom The Kraków Pogrom of 11 August 1945 against the Comparative Background 1. The aim of the conducted research/the research hypothesis The subject of the project is the analysis of the Kraków pogrom of August 1945 against the background of the preceding similar events in Poland (Rzeszów, June 1945) and abroad (Lviv, June 1945), as well as the Slovak and Hungarian pogroms at different times and places. The undertaking is a continuation of the research described in my book "Pod klątwą. Społeczny portret pogromu kieleckiego" (2018), in which I worked out a methodology of microhistorical analysis, allowing the composition of a pogrom crowd to be determined in a maximally objective manner. Thanks to the extensive biographical query it was possible to specify the composition of the forces of law and order of the Citizens' Militia (MO), the Internal Security Corps (KBW), and the Polish Army that were sent to suppress the Kielce pogrom, as well as to put forward hypotheses associated with the genesis of the event. The question which I will address in the presented project concerns the similarities and differences that exist between the pattern according to which the Kielce and Kraków pogroms developed. To what extent did the people who were within the structures of the forces of law and order, primarily communist militia, take part in it –those who murdered Jews during the war? Are the acts of anti-Semitic violence on the Polish, Ukrainian, and Slovak lands structurally similar or fundamentally different? What are the roles of the legend of blood (blood libel), the stereotype of Żydokomuna (Jewish communists), and demographical panic and panic connected with equal rights for Jews, which destabilised traditional social relations? In the framework of preparatory work I managed to initiate the studies on the Kraków pogrom in the IPN Archive (Institute of National Remembrance) and significantly advance the studies concerning the Ukrainian, Hungarian, and Slovak pogroms (the query was financed from the funds from the Marie Curie grant). -

Biuletynbiuletyn Instytutuinstytutu Pamięcipamięci Narodowejnarodowej

NR 3–4 (62–63) marzec–kwiecień 2006 BIULETYNBIULETYN INSTYTUTUINSTYTUTU PAMIĘCIPAMIĘCI NARODOWEJNARODOWEJ Spod czerwonej ISSN 1641-9561 gwiazdy 9 771641 956001 numer indeksu 374431 nakład 3500 egz. cena 7,50 zł (w(w tymtym 0%0% VAT)VAT) ADRESY I TELEFONY ODDZIAŁÓW IPN W POLSCE BIAŁYSTOK ul. Warsztatowa 1a, 15-637 Białystok tel. (0-85) 664 57 03 GDYNIA ul. Witomińska 19, 81-311 Gdynia tel. (0-58) 660 67 00 fax (0-58) 660 67 01 KATOWICE ul. Kilińskiego 9, 40-061 Katowice tel. (0-32) 609 98 40 KRAKÓW ul. Reformacka 3, 31-012 Kraków tel. (0-12) 421 11 00 LUBLIN ul. Wieniawska 15, 20-071 Lublin tel. (0-81) 534 59 11 ŁÓDŹ ul. Orzeszkowej 31/35, 91-479 Łódź tel. (0-42) 616 27 45 POZNAŃ ul. Rolna 45a, 61-487 Poznań tel. (0-61) 835 69 00 RZESZÓW ul. Słowackiego 18, 35-060 Rzeszów tel. (0-17) 860 60 18 SZCZECIN ul. K. Janickiego 30, 71-270 Szczecin tel. (0-91) 484 98 00 WARSZAWA pl. Krasińskich 2/4/6, 00-207 Warszawa tel. (0-22) 530 86 25 WROCŁAW ul. Sołtysowicka 23, 51-168 Wrocław tel. (0-71) 326 76 00 BIULETYN INSTYTUTU PAMIĘCI NARODOWEJ Redaguje Biuro Edukacji Publicznej IPN Zespół redakcyjny: Władysław Bułhak (redaktor naczelny), Janusz Kotański, Krzysztof Madej, Bartłomiej Noszczak, Barbara Polak, Jan M. Ruman, Jan Żaryn Projekt graficzny: Krzysztof Findziński Redakcja techniczna: Andrzej Broniak Skład i łamanie: Wojciech Czaplicki Korekta: Anna Kaniewska Adres: ul. Towarowa 28, 00-839 Warszawa Tel. (0-22) 581 89 24, fax (0-22) 581 89 26 e-mail: [email protected] http://www.ipn.gov.pl Druk: Instytut Technologii Eksploatacji ul. -

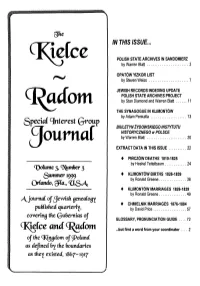

{Journal by Warren Blatt 2 0 EXTRACT DATA in THIS ISSUE 2 2

/N TH/S /SSUE... POLISH STATE ARCHIVES IN SANDOMIERZ by Warren Blatt 3 OPATÔWYIZKORLIST by Steven Weiss 7 JEWISH RECORDS INDEXING UPDATE POLISH STATE ARCHIVES PROJECT by Stan Diamond and Warren Blatt 1 1 THE SYNAGOGUE IN KLIMONTÔW by Adam Penkalla 1 3 Qpedd interest Qroup BIULETYN ZYDOWSKIEGOINSTYTUTU HISTORYCZNEGO w POLSCE {journal by Warren Blatt 2 0 EXTRACT DATA IN THIS ISSUE 2 2 • PINCZÔ W DEATHS 1810-182 5 by Heshel Teitelbaum 2 4 glimmer 1999 • KLIMONTÔ W BIRTHS 1826-183 9 by Ronald Greene 3 8 • KLIMONTÔ W MARRIAGES 1826-183 9 by Ronald Greene 4 9 o • C H Ml ELN IK MARRIAGES 1876-188 4 covering tfte Qufoernios of by David Price 5 7 and <I^ GLOSSARY, PRONUNCIATION GUIDE ... 72 ...but first a word from your coordinator 2 ojtfk as <kpne as tfie^ existed, Kieke-Radom SIG Journal, VoL 3 No. 3 Summer 1999 ... but first a word from our coordinator It has been a tumultuous few months since our last periodical. Lauren B. Eisenberg Davis, one of the primary founders of our group, Special Merest Group and the person who so ably was in charge of research projects at the SIG, had to step down from her responsibilities because of a serious journal illness in her family and other personal matters. ISSN No. 1092-800 6 I remember that first meeting in Boston during the closing Friday ©1999, all material this issue morning hours of the Summer Seminar. Sh e had called a "birds of a feather" meeting for all those genealogists interested in forming a published quarterly by the special interest group focusing on the Kielce and Radom gubernias of KIELCE-RADOM Poland. -

Polish-Jewish Genealogical Research Handout

Polish-Jewish Genealogical Research Warren Blatt HISTORICAL OVERVIEW OF POLISH BORDER CHANGES: 1795 — 3rd and final partition of Poland; Poland ceases to exist as a nation. Northern and western areas (Poznañ, Kalisz, Warsaw, £om¿a, Bia³ystok) taken by Prussia; Eastern areas (Vilna, Grodno, Brest) taken by Russia; Southern areas (Kielce, Radom, Lublin, Siedlce) becomes part of Austrian province of West Galicia. 1807 — Napoleon defeats Prussia; establishes Grand Duchy of Warsaw from former Prussian territory. 1809 — Napoleon defeats Austria; West Galicia (includes most of future Kielce-Radom-Lublin-Siedlce gubernias) becomes part of Napoleon's Duchy of Warsaw. 1815 — Napoleon defeated at Waterloo; Congress of Vienna establishes “Kingdom of Poland” (aka “Congress Poland” or “Russian Poland”) from former Duchy of Warsaw, as part of the Russian Empire; Galicia becomes part of Austro-Hungarian Empire; Western provinces are retained by Prussia. 1918 — End of WWI. Poland reborn at Versailles, but only comprising 3/5ths the size of pre-partition Poland. 1945 — End of WWII. Polish borders shift west: loses territory to U.S.S.R., gains former German areas. LOCATING THE ANCESTRAL SHTETL: _______, Gemeindelexikon der Reichsrate vertretenen Königreiche und Länder [Gazetteer of the Crown Lands and Territories Represented in the Imperial Council]. (Vienna, 1907). {Covers former Austrian territory}. _______, Spis Miejscowoœci Polskiej Rzeczypospolitej Ludowej [Place Names in the Polish Peoples' Republic]. (Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Komunicacji i Lacznosci, 1967). _______, Wykas Wredowych Nazw Miejscowoœci w Polsce [A List of Official Geographic Place Names in Poland]. (Warszawa: Wydawnictwa Akcydensowe, 1880). Barthel, Stephen S. and Daniel Schlyter. “Using Prussian Gazetteers to Locate Jewish Religious and Civil Records in Poznan”, in Avotaynu, Vol. -

Jan Karski Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf187001bd No online items Register of the Jan Karski papers Finding aid prepared by Irena Czernichowska and Zbigniew L. Stanczyk Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 2003 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Register of the Jan Karski papers 46033 1 Title: Jan Karski papers Date (inclusive): 1939-2007 Collection Number: 46033 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: Polish Physical Description: 20 manuscript boxes, 11 oversize boxes, 1 oversize folder, 6 card file boxes, 24 photo envelopes, and 26 microfilm reels(21.8 Linear Feet) Abstract: Correspondence, memoranda, government documents, bulletins, reports, studies, speeches and writings, printed matter, photographs, clippings, newspapers, periodicals, sound recordings, videotape cassettes, and microfilm, relating to events and conditions in Poland during World War II, the German and Soviet occupations of Poland, treatment of the Jews in Poland during the German occupation, and operations of the Polish underground movement during World War II. Includes microfilm copies of Polish underground publications. Boxes 1-34 also available on microfilm (24 reels). Video use copies of videotape available. Sound use copies of sound recordings available. Creator: Karski, Jan, 1914-2000 Hoover Institution Library & Archives Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Acquisition Information Materials were acquired by the Hoover Institution Library & Archives from 1946 to 2008. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Jan Karski papers, [Box no., Folder no. -

Construction of a New Rail Link from Warsaw Służewiec to Chopin Airport and Modernisation of the Railway Line No

Ex post evaluation of major projects supported by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) and Cohesion Fund between 2000 and 2013 Construction of a new rail link from Warsaw Służewiec to Chopin Airport and modernisation of the railway line no. 8 between Warsaw Zachodnia (West) and Warsaw Okęcie station Poland EUROPEAN COMMISSION Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy Directorate Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy Unit Evaluation and European Semester Contact: Jan Marek Ziółkowski E-mail: [email protected] European Commission B-1049 Brussels EUROPEAN COMMISSION Ex post evaluation of major projects supported by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) and Cohesion Fund between 2000 and 2013 Construction of a new rail link from Warsaw Służewiec to Chopin Airport and modernisation of the railway line no. 8 between Warsaw Zachodnia (West) and Warsaw Okęcie station Poland Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy 2020 EN Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union. Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) The information given is free, as are most calls (though some operators, phone boxes or hotels may charge you). Manuscript completed in 2018 The European Commission is not liable for any consequence stemming from the reuse of this publication. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2020 ISBN 978-92-76-17419-6 doi: 10.2776/631494 © European Union, 2020 Reuse is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. The reuse policy of European Commission documents is regulated by Decision 2011/833/EU (OJ L 330, 14.12.2011, p. -

No Haven for the Oppressed

No Haven for the Oppressed NO HAVEN for the Oppressed United States Policy Toward Jewish Refugees, 1938-1945 by Saul S. Friedman YOUNGSTOWN STATE UNIVERSITY Wayne State University Press Detroit 1973 Copyright © 1973 by Wayne State University Press, Detroit, Michigan 48202. All material in this work, except as identified below, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/us/. Excerpts from Arthur Miller’s Incident at Vichy formerly copyrighted © 1964 to Penguin Publishing Group now copyrighted to Penguin Random House. All material not licensed under a Creative Commons license is all rights reserved. Permission must be obtained from the copyright owner to use this material. Published simultaneously in Canada by the Copp Clark Publishing Company 517 Wellington Street, West Toronto 2B, Canada. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Friedman, Saul S 1937– No haven for the oppressed. Originally presented as the author’s thesis, Ohio State University. Includes bibliographical references. 1. Refugees, Jewish. 2. Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945) 3. United States— Emigration and immigration. 4. Jews in the United States—Political and social conditions. I. Title. D810.J4F75 1973 940.53’159 72-2271 ISBN 978-0-8143-4373-9 (paperback); 978-0-8143-4374-6 (ebook) Publication of this book was assisted by the American Council of Learned Societies under a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. The publication of this volume in a freely accessible digital format has been made possible by a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Mellon Foundation through their Humanities Open Book Program. -

Who Were the Prusai ?

WHO WERE THE PRUSAI ? So far science has not been able to provide answers to this question, but it does not mean that we should not begin to put forward hypotheses and give rise to a constructive resolution of this puzzle. Great help in determining the ethnic origin of Prusai people comes from a new branch of science - genetics. Heraldically known descendants of the Prusai, and persons unaware of their Prusai ethnic roots, were subject to the genetic test, thus provided a knowledge of the genetics of their people. In conjunction with the historical knowledge, this enabled to be made a conclusive finding and indicated the territory that was inhabited by them. The number of tests must be made in much greater number in order to eliminate errors. Archaeological research and its findings also help to solve this question, make our knowledge complemented and compared with other regions in order to gain knowledge of Prusia, where they came from and who they were. Prusian people provinces POMESANIA and POGESANIA The genetic test done by persons with their Pomesanian origin provided results indicating the Haplogroup R1b1b2a1b and described as the Atlantic Group or Italo-Celtic. The largest number of the people from this group, today found between the Irish and Scottish Celts. Genetic age of this haplogroup is older than that of the Celt’s genetics, therefore also defined as a proto Celtic. 1 The Pomerania, Poland’s Baltic coast, was inhabited by Gothic people called Gothiscanza. Their chronicler Cassiodor tells that they were there from 1940 year B.C. Around the IV century A.D. -

Poland Study Guide Poland Study Guide

Poland Study Guide POLAND STUDY GUIDE POLAND STUDY GUIDE Table of Contents Why Poland? In 1939, following a nonaggression agreement between the Germany and the Soviet Union known as the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, Poland was again divided. That September, Why Poland Germany attacked Poland and conquered the western and central parts of Poland while the Page 3 Soviets took over the east. Part of Poland was directly annexed and governed as if it were Germany (that area would later include the infamous Nazi concentration camp Auschwitz- Birkenau). The remaining Polish territory, the “General Government,” was overseen by Hans Frank, and included many areas with large Jewish populations. For Nazi leadership, Map of Territories Annexed by Third Reich the occupation was an extension of the Nazi racial war and Poland was to be colonized. Page 4 Polish citizens were resettled, and Poles who the Nazis deemed to be a threat were arrested and shot. Polish priests and professors were shot. According to historian Richard Evans, “If the Poles were second-class citizens in the General Government, then the Jews scarcely Map of Concentration Camps in Poland qualified as human beings at all in the eyes of the German occupiers.” Jews were subject to humiliation and brutal violence as their property was destroyed or Page 5 looted. They were concentrated in ghettos or sent to work as slave laborers. But the large- scale systematic murder of Jews did not start until June 1941, when the Germans broke 2 the nonaggression pact with the Soviets, invaded the Soviet-held part of Poland, and sent 3 Chronology of the Holocaust special mobile units (the Einsatzgruppen) behind the fighting units to kill the Jews in nearby forests or pits. -

Pogrom Ludności Żydowskiej W Kielcach Z 11-12 Listopada 1918 Roku

Facta Simonidis, 2017 nr 1 (10) Dominik Flisiak Uniwersytet Jana Kochanowskiego w Kielcach [email protected] Pogrom ludności żydowskiej w Kielcach z 11-12 listopada 1918 roku. Przyczyny, przebieg, konsekwencje. The pogrom of Jews in Kielce, 11-12 November 1918. Causes, course, consequences Streszczenie: Pierwszy pogrom w Kielcach miał miejsce w dniach 11-12 listopada 1918 r. Po- wodem tych wydarzeń było niesłuszne oskarżenia wysuwane przez niektórych Polaków wobec starozakonnych o chęć stworzenia w Polsce państwa żydowskiego tzw. Judeo- Po- lonii. Do wybuchu zamieszek doszło w dniu 11 listopada w trakcie zebrania syjonistów, które miało miejsce w Teatrze Apollo. W wyniku niewyjaśnionych do dnia dzisiejszego okoliczności część kielczan zaatakowała zgromadzonych w teatrze syjonistów. Śmierć wtedy poniosło czterech Żydów. W ramach artykułu zaprezentowane będą relacje pol- sko- żydowskie w Kielcach, przebieg pogromu i jego skutki. Słowa kluczowe: Kielce, pogrom, antysemityzm, rok 1918 Summary: The first pogrom in Kielce took place on 11 and 12 November 1918. The reason for these events was unjust accusation of Jews by some Poles desiring to create a Jewish state in Poland the so called Judeo-Polonia. Riots took place on November 11 during the meeting of the Zionists, which took place at the Apollo Theatre. As a result of some unexplained to this day circumstances Kielce citizens attacked Zionists gathered in the theater, which resulted in the death of four Jews. In this article the Polish-Jewish rela- tions, the course of the pogrom, and its aftermath will be presented. Keywords: Kielce pogrom, anti-Semitism, 1918 243 Dominik Flisiak 1. Relacje polsko-żydowskie w Kielcach przed wybuchem I wojny światowej Na przełomie XIX/XX w.