Kielce Province Villages During WWII (Pdf, 150.77

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“He Was One of Us” – Joseph Conrad As a Home Army Author

Yearbook of Conrad Studies (Poland) Vol. 13 2018, pp. 17–29 doi: 0.4467/20843941YC.18.002.11237 “HE WAS ONE OF US” – JOSEPH CONRAD AS A HOME ARMY AUTHOR Stefan Zabierowski The University of Silesia, Katowice Abstract: The aim of this article is to show how Conrad’s fiction (and above all the novelLord Jim) influenced the formation of the ethical attitudes and standards of the members of the Polish Home Army, which was the largest underground army in Nazi-occupied Europe. The core of this army was largely made up of young people who had been born around the year 1920 (i.e. after Poland had regained her independence in 1918) and who had had the opportunity to become acquainted with Conrad’s books during the interwar years. During the wartime occupation, Conrad became the fa- vourite author of those who were actively engaged in fighting the Nazi regime, familiarizing young conspirators with the ethics of honour—the conviction that fighting in a just cause was a reward in itself, regardless of the outcome. The views of this generation of soldiers have been recorded by the writers who were among them: Jan Józef Szczepański, Andrzej Braun and Leszek Prorok. Keywords: Joseph Conrad, World War II, Poland, Polish Home Army, Home Army, Warsaw Uprising 1 In order to fully understand the extraordinary role that Joseph Conrad’s novels played in forming the ethical attitudes and standards of those Poles who fought in the Home Army—which was the largest underground resistance army in Nazi-occupied Europe—we must go back to the interwar years, during which most of the members of the generation that was to form the core of the Home Army were born, for it was then that their personalities were formed and—perhaps above all—it was then that they acquired the particular ethos that they had in common. -

The Archives of Poland and Where to Find Online Genealogy Records for Each - Sheet1

The Archives of Poland and where to find Online Genealogy Records for each - Sheet1 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License Archives of Poland Territorial coverage Search theGenBaza ArchivesGenetekaJRI-PolandAGAD Przodek.plGesher Archeion.netGalicia LubgensGenealogyPoznan in the BaSIAProject ArchivesPomGenBaseSzpejankowskisPodlaskaUpper and Digital Szpejenkowski SilesianSilesian Library Genealogical Digital Library Society Central Archives of Historical Records All Poland ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ National Digital Archive All Poland ✓ ✓ Central Archives of Modern Records All Poland ✓ ✓ Podlaskie (primarily), State Archive in Bialystok Masovia ✓ ✓ ✓ The Archives of Poland and where to find Online Genealogy Records for each - Sheet1 Branch in Lomza Podlaskie ✓ ✓ Kuyavian-Pomerania (primarily), Pomerania State Archive in Bydgoszcz and Greater Poland ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Kuyavian-Pomerania (primarily), Greater Branch in Inowrocław Poland ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Silesia (primarily), Świetokrzyskie, Łódz, National Archives in Częstochowa and Opole ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Pomerania (primarily), State Archive in Elbląg with the Warmia-Masuria, Seat in Malbork Kuyavian-Pomerania ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ State Archive in Gdansk Pomerania ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Gdynia Branch Pomerania ✓ ✓ ✓ State Archive in Gorzow Lubusz (primarily), Wielkopolski Greater Poland ✓ ✓ ✓ Greater Poland (primarily), Łódz, State Archive in Kalisz Lower Silesia ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Silesia (primarily), State Archive in Katowice Lesser Poland ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Branch in Bielsko-Biala Silesia ✓ ✓ ✓ Branch in Cieszyn Silesia ✓ ✓ ✓ Branch -

Copyright © London Branch of the Polish Home Army Ex-Servicemen Association Copying Permitted with Reference to Source and Authors

Copyright © London Branch of the Polish Home Army Ex-Servicemen Association Copying permitted with reference to source and authors www.polishresistance-ak.org Article 17 Dr Grzegorz Ostasz, The Polish Government-in-Exile's Home Delegature During the Second World War the Polish Underground State was based on a collection of political and military organisations striving for independence. These were formed throughout Polish territories, then under German and Soviet occupation. The long tradition of struggles for independence was conducive to their creation. Already in the autumn of 1939 measures were taken to appoint an underground central administrative authority that would be a continuation of the pre-war state administration. The Statute of Service for Victory in Poland referred to the necessity of creating ‘a provisional national authority on home territory’. Likewise General Wladyslaw Sikorski’s cabinet endeavoured to establish a governmental executive organ in occupied Poland. At the start of 1940 it was decided that a home territories civilian commissioner would be granted ministerial prerogatives and hold the position of the Government-in-Exile’s delegate (plenipotentiary). Hope of the imminent defeat of the occupying powers and a repetition of the First World War scenario hastened the construction of a government administration ready to take over control of a liberated and ‘unclaimed Polish land’. The tasks of such an organisation were to include: cooperating with the Government-in-Exile (allied to France and Great Britain) and the Union for Armed Struggle (later the Home Army); participating in the planning of a general rising; consolidating the Polish community and directing its resistance to the German-Soviet occupation. -

Joint Force Quarterly 97

Issue 97, 2nd Quarter 2020 JOINT FORCE QUARTERLY Broadening Traditional Domains Commercial Satellites and National Security Ulysses S. Grant and the U.S. Navy ISSUE NINETY-SEVEN, 2 ISSUE NINETY-SEVEN, ND QUARTER 2020 Joint Force Quarterly Founded in 1993 • Vol. 97, 2nd Quarter 2020 https://ndupress.ndu.edu GEN Mark A. Milley, USA, Publisher VADM Frederick J. Roegge, USN, President, NDU Editor in Chief Col William T. Eliason, USAF (Ret.), Ph.D. Executive Editor Jeffrey D. Smotherman, Ph.D. Production Editor John J. Church, D.M.A. Internet Publications Editor Joanna E. Seich Copyeditor Andrea L. Connell Associate Editor Jack Godwin, Ph.D. Book Review Editor Brett Swaney Art Director Marco Marchegiani, U.S. Government Publishing Office Advisory Committee Ambassador Erica Barks-Ruggles/College of International Security Affairs; RDML Shoshana S. Chatfield, USN/U.S. Naval War College; Col Thomas J. Gordon, USMC/Marine Corps Command and Staff College; MG Lewis G. Irwin, USAR/Joint Forces Staff College; MG John S. Kem, USA/U.S. Army War College; Cassandra C. Lewis, Ph.D./College of Information and Cyberspace; LTG Michael D. Lundy, USA/U.S. Army Command and General Staff College; LtGen Daniel J. O’Donohue, USMC/The Joint Staff; Brig Gen Evan L. Pettus, USAF/Air Command and Staff College; RDML Cedric E. Pringle, USN/National War College; Brig Gen Kyle W. Robinson, USAF/Dwight D. Eisenhower School for National Security and Resource Strategy; Brig Gen Jeremy T. Sloane, USAF/Air War College; Col Blair J. Sokol, USMC/Marine Corps War College; Lt Gen Glen D. VanHerck, USAF/The Joint Staff Editorial Board Richard K. -

Translator's Introductory Note

Report ‘W’ KL Auschwitz 1940 – 1943 by Captain Witold Pilecki Copyright © by Andrzej Nowak and Hubert Blaszczyk, President of the Association of Polish Political Prisoners in Australia, 2013([email protected], [email protected]) Copyright © translations Report W (IPN BU 0259/168 t 6) by Dr. Adam J. Koch Acknowledgements: Hubert Blaszczyk, President of the Association of Polish Political Prisoners in Australia The Editorial Board gratefully acknowledges the support and financial generosity of Isis Pacific Pty Ltd in publishing of this book. The Editorial Board wishes to thank Mr. Jacek Glinka for his dedication to design and graphic setting of our book. Foreword: Dr.George Luk-Kozik, Honorary Consul-General for Republic of Poland Admission (A Yesteryear's hero?) and afterword (Instead of an Epilogue): Dr. Adam J. Koch My Tribute to Pilecki: Andrzej Nowak Biography: Publishers, translated by Krzysztof Derwinski Project coordinators: Andrzej Nowak, Jacek Glinka, Andrzej Balcerzak, Hubert Blaszczyk Project Contributors: Jerzy Wieslaw Fiedler, Zbigniew Leman, Zofia Kwiatkowska-Dublaszewski, Bogdan Platek, Dr. Zdzislaw Derwinski Editors: Dr. Adam Koch, Jacek Glinka, Andrzej Nowak; Graphic Design: Daniel Brewinski Computer processing of text: Jacek Glinka Publishers: Andrzej Nowak with the Polish Association of Political Prisoners in Australia All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, without the prior permission of publishers. Picture Sources: The publishers wish to express their thanks to the following sources of illustrative material and/or permission to reproduce it. They will make the proper acknowledgements in future editions in the event that any omissions have occurred. IPN (Institute of National Remembrance) in Poland, Institute’s Bureau of Access and Documents Archivization, copies of original documents from IPN and Album ‘Rotmistrz Witold Pilecki 1901- 1948’ by Jacek Pawłowicz of IPN. -

THE POLISH POLICE Collaboration in the Holocaust

THE POLISH POLICE Collaboration in the Holocaust Jan Grabowski The Polish Police Collaboration in the Holocaust Jan Grabowski INA LEVINE ANNUAL LECTURE NOVEMBER 17, 2016 The assertions, opinions, and conclusions in this occasional paper are those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. First printing, April 2017 Copyright © 2017 by Jan Grabowski THE INA LEVINE ANNUAL LECTURE, endowed by the William S. and Ina Levine Foundation of Phoenix, Arizona, enables the Center to bring a distinguished scholar to the Museum each year to conduct innovative research on the Holocaust and to disseminate this work to the American public. Wrong Memory Codes? The Polish “Blue” Police and Collaboration in the Holocaust In 2016, seventy-one years after the end of World War II, the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs disseminated a long list of “wrong memory codes” (błędne kody pamięci), or expressions that “falsify the role of Poland during World War II” and that are to be reported to the nearest Polish diplomat for further action. Sadly—and not by chance—the list elaborated by the enterprising humanists at the Polish Foreign Ministry includes for the most part expressions linked to the Holocaust. On the long list of these “wrong memory codes,” which they aspire to expunge from historical narrative, one finds, among others: “Polish genocide,” “Polish war crimes,” “Polish mass murders,” “Polish internment camps,” “Polish work camps,” and—most important for the purposes of this text—“Polish participation in the Holocaust.” The issue of “wrong memory codes” will from time to time reappear in this study. -

3868546065 Lp.Pdf

Studien zur Gewaltgeschichte des 20. Jahrhunderts Ausgewählt von Jörg Baberowski, Bernd Greiner und Michael Wildt Das 20. Jahrhundert gilt als das Jahrhundert des Genozids, der Lager, des Totalen Krieges, des Totalitarismus und Ter- rorismus, von Flucht, Vertreibung und Staatsterror – ge- rade weil sie im Einzelnen allesamt zutreffen, hinterlassen diese Charakterisierungen in ihrer Summe eine eigentüm- liche Ratlosigkeit. Zumindest spiegeln sie eine nachhaltige Desillusionierung. Die Vorstellung, Gewalt einhegen, be- grenzen und letztlich überwinden zu können, ist der Ein- sicht gewichen, dass alles möglich ist, jederzeit und an jedem Ort der Welt. Und dass selbst Demokratien, die Erben der Aufklärung, vor entgrenzter Gewalt nicht gefeit sind. Das normative und ethische Bemühen, die Gewalt einzugrenzen, mag vor diesem Hintergrund ungenügend und mitunter sogar vergeblich erscheinen. Hinfällig ist es aber keineswegs, es sei denn um den Preis der moralischen Selbstaufgabe. Ausgewählt von drei namhaften Historikern – Jörg Baberowski, Bernd Greiner und Michael Wildt –, präsen- tieren die »Studien zur Gewaltgeschichte des 20. Jahrhun- derts« die Forschungsergebnisse junger Wissenschaftle- rinnen und Wissenschaftler. Die Monografien analysieren am Beispiel von totalitären Systemen wie dem National- sozialismus und Stalinismus, von Diktaturen, Autokratien und nicht zuletzt auch von Demokratien die Dynamik ge- walttätiger Situationen, sie beschreiben das Erbe der Ge- walt und skizzieren mögliche Wege aus der Gewalt. Sara Berger Experten der Vernichtung -

Guides to German Records Microfilmed at Alexandria, Va

GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA. No. 32. Records of the Reich Leader of the SS and Chief of the German Police (Part I) The National Archives National Archives and Records Service General Services Administration Washington: 1961 This finding aid has been prepared by the National Archives as part of its program of facilitating the use of records in its custody. The microfilm described in this guide may be consulted at the National Archives, where it is identified as RG 242, Microfilm Publication T175. To order microfilm, write to the Publications Sales Branch (NEPS), National Archives and Records Service (GSA), Washington, DC 20408. Some of the papers reproduced on the microfilm referred to in this and other guides of the same series may have been of private origin. The fact of their seizure is not believed to divest their original owners of any literary property rights in them. Anyone, therefore, who publishes them in whole or in part without permission of their authors may be held liable for infringement of such literary property rights. Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 58-9982 AMERICA! HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION COMMITTEE fOR THE STUDY OP WAR DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECOBDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXAM)RIA, VA. No* 32» Records of the Reich Leader of the SS aad Chief of the German Police (HeiehsMhrer SS und Chef der Deutschen Polizei) 1) THE AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION (AHA) COMMITTEE FOR THE STUDY OF WAE DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA* This is part of a series of Guides prepared -

They Fought for Independent Poland

2019 Special edition PISMO CODZIENNE Independence Day, November 11, 2019 FREE AGAIN! THEY FOUGHT FOR INDEPENDENT POLAND Dear Readers, The day of November 11 – the National Independence Day – is not accidentally associated with the Polish military uni- form, its symbolism and traditions. Polish soldiers on almost all World War I fronts “threw on the pyre their lives’ fate.” When the Polish occupiers were drown- ing in disasters and revolutions, white- and-red flags were fluttering on Polish streets to mark Poland’s independence. The Republic of Poland was back on the map of Europe, although this was only the beginning of the battle for its bor- ders. Józef Piłsudski in his first order to the united Polish Army shared his feeling of joy with his soldiers: “I’m taking com- mand of you, Soldiers, at the time when the heart of every Pole is beating stron- O God! Thou who from on high ger and faster, when the children of our land have seen the sun of freedom in all its Hurls thine arrows at the defenders of the nation, glory.” He never promised them any bat- We beseech Thee, through this heap of bones! tle laurels or well-merited rest, though. On the contrary – he appealed to them Let the sun shine on us, at least in death! for even greater effort in their service May the daylight shine forth from heaven’s bright portals! for Poland. And they never let him down Let us be seen - as we die! when in 1920 Poland had to defend not only its own sovereignty, but also entire Europe against flooding bolshevism. -

{Journal by Warren Blatt 2 0 EXTRACT DATA in THIS ISSUE 2 2

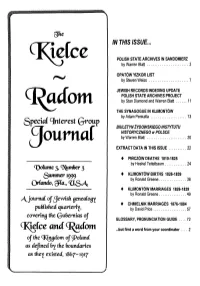

/N TH/S /SSUE... POLISH STATE ARCHIVES IN SANDOMIERZ by Warren Blatt 3 OPATÔWYIZKORLIST by Steven Weiss 7 JEWISH RECORDS INDEXING UPDATE POLISH STATE ARCHIVES PROJECT by Stan Diamond and Warren Blatt 1 1 THE SYNAGOGUE IN KLIMONTÔW by Adam Penkalla 1 3 Qpedd interest Qroup BIULETYN ZYDOWSKIEGOINSTYTUTU HISTORYCZNEGO w POLSCE {journal by Warren Blatt 2 0 EXTRACT DATA IN THIS ISSUE 2 2 • PINCZÔ W DEATHS 1810-182 5 by Heshel Teitelbaum 2 4 glimmer 1999 • KLIMONTÔ W BIRTHS 1826-183 9 by Ronald Greene 3 8 • KLIMONTÔ W MARRIAGES 1826-183 9 by Ronald Greene 4 9 o • C H Ml ELN IK MARRIAGES 1876-188 4 covering tfte Qufoernios of by David Price 5 7 and <I^ GLOSSARY, PRONUNCIATION GUIDE ... 72 ...but first a word from your coordinator 2 ojtfk as <kpne as tfie^ existed, Kieke-Radom SIG Journal, VoL 3 No. 3 Summer 1999 ... but first a word from our coordinator It has been a tumultuous few months since our last periodical. Lauren B. Eisenberg Davis, one of the primary founders of our group, Special Merest Group and the person who so ably was in charge of research projects at the SIG, had to step down from her responsibilities because of a serious journal illness in her family and other personal matters. ISSN No. 1092-800 6 I remember that first meeting in Boston during the closing Friday ©1999, all material this issue morning hours of the Summer Seminar. Sh e had called a "birds of a feather" meeting for all those genealogists interested in forming a published quarterly by the special interest group focusing on the Kielce and Radom gubernias of KIELCE-RADOM Poland. -

Polish-Jewish Genealogical Research Handout

Polish-Jewish Genealogical Research Warren Blatt HISTORICAL OVERVIEW OF POLISH BORDER CHANGES: 1795 — 3rd and final partition of Poland; Poland ceases to exist as a nation. Northern and western areas (Poznañ, Kalisz, Warsaw, £om¿a, Bia³ystok) taken by Prussia; Eastern areas (Vilna, Grodno, Brest) taken by Russia; Southern areas (Kielce, Radom, Lublin, Siedlce) becomes part of Austrian province of West Galicia. 1807 — Napoleon defeats Prussia; establishes Grand Duchy of Warsaw from former Prussian territory. 1809 — Napoleon defeats Austria; West Galicia (includes most of future Kielce-Radom-Lublin-Siedlce gubernias) becomes part of Napoleon's Duchy of Warsaw. 1815 — Napoleon defeated at Waterloo; Congress of Vienna establishes “Kingdom of Poland” (aka “Congress Poland” or “Russian Poland”) from former Duchy of Warsaw, as part of the Russian Empire; Galicia becomes part of Austro-Hungarian Empire; Western provinces are retained by Prussia. 1918 — End of WWI. Poland reborn at Versailles, but only comprising 3/5ths the size of pre-partition Poland. 1945 — End of WWII. Polish borders shift west: loses territory to U.S.S.R., gains former German areas. LOCATING THE ANCESTRAL SHTETL: _______, Gemeindelexikon der Reichsrate vertretenen Königreiche und Länder [Gazetteer of the Crown Lands and Territories Represented in the Imperial Council]. (Vienna, 1907). {Covers former Austrian territory}. _______, Spis Miejscowoœci Polskiej Rzeczypospolitej Ludowej [Place Names in the Polish Peoples' Republic]. (Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Komunicacji i Lacznosci, 1967). _______, Wykas Wredowych Nazw Miejscowoœci w Polsce [A List of Official Geographic Place Names in Poland]. (Warszawa: Wydawnictwa Akcydensowe, 1880). Barthel, Stephen S. and Daniel Schlyter. “Using Prussian Gazetteers to Locate Jewish Religious and Civil Records in Poznan”, in Avotaynu, Vol. -

Nihil Novi #3

The Kos’ciuszko Chair of Polish Studies Miller Center of Public Affairs University of Virginia Charlottesville, Virginia Bulletin Number Three Fall 2003 On the Cover: The symbol of the KoÊciuszko Squadron was designed by Lt. Elliot Chess, one of a group of Americans who helped the fledgling Polish air force defend its skies from Bolshevik invaders in 1919 and 1920. Inspired by the example of Tadeusz KoÊciuszko, who had fought for American independence, the American volunteers named their unit after the Polish and American hero. The logo shows thirteen stars and stripes for the original Thirteen Colonies, over which is KoÊciuszko’s four-cornered cap and two crossed scythes, symbolizing the peasant volunteers who, led by KoÊciuszko, fought for Polish freedom in 1794. After the Polish-Bolshevik war ended with Poland’s victory, the symbol was adopted by the Polish 111th KoÊciuszko Squadron. In September 1939, this squadron was among the first to defend Warsaw against Nazi bombers. Following the Polish defeat, the squadron was reformed in Britain in 1940 as Royal Air Force’s 303rd KoÊciuszko. This Polish unit became the highest scoring RAF squadron in the Battle of Britain, often defending London itself from Nazi raiders. The 303rd bore this logo throughout the war, becoming one of the most famous and successful squadrons in the Second World War. The title of our bulletin, Nihil Novi, invokes Poland’s ancient constitution of 1505. It declared that there would be “nothing new about us without our consent.” In essence, it drew on the popular sentiment that its American version expressed as “no taxation without representation.” The Nihil Novi constitution guar- anteed that “nothing new” would be enacted in the country without the consent of the Parliament (Sejm).