Talk on Sweden

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliography

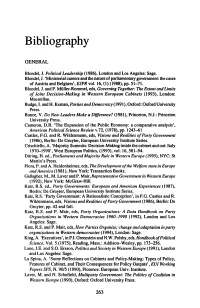

Bibliography GENERAL Blonde!, J. Political Leadership (1986), London and Los Angeles: Sage. Blonde!, J. 'Ministerial careers and the nature of parliamentary government: the cases of Austria and Belgium', EJPR vol. 16, (l) (1988), pp. 51-71. Blonde!, J. and F. MUller-Rommel, eds, Governing Together: Tile Extent and Limits of Joint Decision-Making in Western European Cabinets (1993), London: Macmillan. Budge, I. and H. Kernan, Parties and Democracy ( 1991 ), Oxford: Oxford University Press. Bunce, V. Do New Leaders Make a Difference? (1981), Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. Cameron, D.R. 'The Expansion of the Public Economy: a comparative analysis', American Political Science Review v.12, (1978), pp. 1243-61 Castles, P.O. and R. Wilden mann, eds, Visions and Realities of Party Government (1986), Berlin: De Gruyter, European University Institute Series. Criscitiello, A. 'Majority Summits: Decision-Making inside the cabinet and out: Italy 1970-1990', West European Politics, (1993), vol. 16, 581-94. Dt>ring, H. ed., Parliaments and Majority Rule in Western Europe (1995), NYC: St Martin's Press. Flora, P. and A. Heidenheimer, eds, The Development ofthe Welfare state in Europe and America (1981), New York: Transaction Books. Gallagher, M., M. Laver and P. Mair, Representative Government in Western Europe (1992), New York: McGraw-Hill. Katz, R.S. ed., Party Govemments: European and American Expe1·iences (1987), Berlin: De Gruyter, European University Institute Series. Katz, R.S. 'Party Government: A Rationalistic Conception', in F. G. Castles and R. Wildenmann, eds, Visions and Realities of Party Government (1986), Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 42 and foil. Katz, R.S. -

The Olof Palme International Center

About The Olof Palme International Center The Olof Palme International Center works with international development co-operation and the forming of public opinion surrounding international political and security issues. The Palme Center was established in 1992 by the Swedish Social Democratic Party, the Trade Union Confederation (LO) and the Cooperative Union (KF). Today the Palme Center has 28 member organizations within the labour movement. The centre works in the spirit of the late Swedish Prime Minister Olof Palme, reflected by the famous quotation: "Politics is wanting something. Social Democratic politics is wanting change." Olof Palme's conviction that common security is created by co-operation and solidarity across borders, permeates the centre's activities. The centre's board is chaired by Lena Hjelm-Wallén, former foreign minister of Sweden. Viola Furubjelke is the centre's Secretary General, and Birgitta Silén is head of development aid. There are 13 members of the board, representing member organisations. The commitment of these member organisations is the core of the centre's activities. Besides the founding organisations, they include the Workers' Educational Association, the tenants' movement, and individual trade unions. As popular movements and voluntary organisations , they are represented in all Swedish municipalities and at many workplaces. An individual cannot be a member of the Palme Center, but the member organisations together have more than three million members. In Sweden, the centre carries out comprehensive information and opinion-forming campaigns on issues concerning international development, security and international relations. This includes a very active schedule of seminars and publications, both printed and an e-mail newsletter. -

(American Swedish News Exchange, New York, NY), 1920S-1990

Allan Kastrup collection (American Swedish News Exchange, New York, N.Y), 1920s-1990 Size: 19.25 linear feet, 28 boxes Acquisition: The collection was donated to SSIRC in 1990 and 1991. Access: The collection is open for research and a limited amount to copies can be requested via mail. Processed by: Christina Johansson Control Num.: SSIRC MSS P: 308 Historical Sketch The American-Swedish News Exchange was established by the Sweden-America Foundation in Stockholm in 1921 and the agency opened its office in New York City in 1922. ASNE's main purpose was to increase and broaden the general knowledge about Sweden and to provide the American press with news on cultural, economic and political developments in Sweden. The agency also had the primary responsibility for publicity campaigns during Swedish official visits to the United States, such as the Crown Prince Gustav Adolf's visit in 1926, the New Sweden Tercentenary in 1938, and the Swedish Pioneer Centennial in 1948. Between 1926 and 1946, ASNE was under the leadership of Naboth Hedin. Hedin increased the visibility of Sweden in the American press immensely, wrote countless of articles on Sweden, and co-edited with Adolph H. Benson Swedes in America: 1638-1938. Hedin was also instrumental in assisting many American writers with advice and information about Sweden; including Marquis W. Childs in his widely read and circulated work Sweden the Middle Way, first published in 1936. Allan Kastrup assumed the leadership of ASNE in 1946. He held this position until his retirement in 1964, at which time ASNE ceased to exist and its responsibilities were assumed by the Swedish Information Service. -

![Arxiv:2106.01515V1 [Cs.LG] 3 Jun 2021 Tor Representations of Entities and Relations in a KG](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4165/arxiv-2106-01515v1-cs-lg-3-jun-2021-tor-representations-of-entities-and-relations-in-a-kg-1054165.webp)

Arxiv:2106.01515V1 [Cs.LG] 3 Jun 2021 Tor Representations of Entities and Relations in a KG

Question Answering Over Temporal Knowledge Graphs Apoorv Saxena Soumen Chakrabarti Partha Talukdar Indian Institute of Science Indian Institute of Technology Google Research Bangalore Bombay India [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract time intervals as well. These temporal scopes on facts can be either automatically estimated (Taluk- Temporal Knowledge Graphs (Temporal KGs) extend regular Knowledge Graphs by provid- dar et al., 2012) or user contributed. Several such ing temporal scopes (e.g., start and end times) Temporal KGs have been proposed in the literature, on each edge in the KG. While Question An- where the focus is on KG completion (Dasgupta swering over KG (KGQA) has received some et al. 2018; Garc´ıa-Duran´ et al. 2018; Leetaru and attention from the research community, QA Schrodt 2013; Lacroix et al. 2020; Jain et al. 2020). over Temporal KGs (Temporal KGQA) is a The task of Knowledge Graph Question Answer- relatively unexplored area. Lack of broad- coverage datasets has been another factor lim- ing (KGQA) is to answer natural language ques- iting progress in this area. We address this tions using a KG as the knowledge base. This is challenge by presenting CRONQUESTIONS, in contrast to reading comprehension-based ques- the largest known Temporal KGQA dataset, tion answering, where typically the question is ac- clearly stratified into buckets of structural com- companied by a context (e.g., text passage) and plexity. CRONQUESTIONS expands the only the answer is either one of multiple choices (Ra- known previous dataset by a factor of 340×. jpurkar et al., 2016) or a piece of text from the We find that various state-of-the-art KGQA methods fall far short of the desired perfor- context (Yang et al., 2018). -

Cabinet Reshuffles and Prime Ministerial Power

Cabinet Reshuffles and Prime Ministerial Power Jörgen Hermansson and Kåre Vernby ***VERY PRELIMINARY “IDEAS-PAPER”*** Abstract This paper contains some ideas about how to transform a paper we wrote together in Swedish for an anthology on Swedish governments 1917-2009. There, we point out that reshuffles are problematic when used as an indicator of prime-ministerial power/dominance over the cabinet. In the future, we wish to expand our critique. In this “ideas paper”, however, we only briefly outline our critique. We will argue that there exist at least two problems inherent in using the frequency of reshuffles as an indicator of Prime-ministerial power over the cabinet. The first we call the “problem of proxying”, which arises because scholars implicitly use the frequency of reshuffles as a proxy for the political experience of the ministers surrounding the PM. Specifically, the frequency of reshuffles is thought to be inversely related to the political experience of ministers. The second problem we call the “problem of selection bias”, which arises because of the failure to properly specifying the possibility of a bi-directional causal relationship between prime-ministerial power and cabinet reshuffles. We will try to argue that these are serious problems for those who wish to use the frequency of cabinet reshuffles as a measure of prime ministerial using historical data and examples from the Swedish history with parliamentarism. 1 Introduction While the formation and collapse of cabinet governments has been a mainstay of political science for more than 50 years, the recent decade has seen a growing pre- occupation with cabinet reshuffles. -

The Corporate Analogy and the Legitimacy of Promoting Sweden Abroad in the 1960S

chapter 6 A Total Image Deconstructed: The Corporate Analogy and the Legitimacy of Promoting Sweden Abroad in the 1960s Nikolas Glover In the spring of 1967, an exhibited print by the well-known leftist artist Carl Johan de Geer was confiscated by the police in Stockholm. It depicted a burning Swedish flag, capped by three slogans: “Dishonour the flag,” “Betray the Fatherland,” “Dare to be non-nationalist.” The flag itself had one word sprawled across it: Kuken, slang for penis. The motif was judged to be in breach of the Swedish constitution (by defiling the flag) and de Geer was fined in court.1 The episode sets the historic scene for this chapter. In the second half of the 1960s, self-proclaimed anti-patriotic sentiments like those voiced by de Geer were gain- ing widespread popularity among artists-cum-activists and within the growing movements of the New Left.2 Meanwhile, publicly funded “Sweden-information abroad” was expanding in scope and ambition.3 This chapter focuses on the rela- tionship between these two developments, showing how practitioners in the field of Sweden-information navigated between the imperatives of efficient communication and democratic legitimacy. At the heart of this challenge lay the need to manage the diverging demands of the government’s foreign policy objec- tives, the export industry’s commercial interests, and a politically active cultural scene that was insisting that it should not have to cooperate with either. Managing Diverging Demands In many respects, representing Sweden abroad in the early 1960s was a thankful task: affluent, ambitiously reformist and technologically advanced, the country 1 “Konsten att göra uppror,” Svenska Dagbladet, 2 December 2007. -

The Impact of Experts on Tax Policy in Post-War Britain and Sweden

Acta Oeconomica, Vol. 67 (S), pp. 79–96 (2017) DOI: 10.1556/032.2017.67.S.7 THE IMPACT OF EXPERTS ON TAX POLICY IN POST-WAR BRITAIN AND SWEDEN Per F. ANDERSSON During the decades after World War II, countries began shifting taxation from income to con- sumption. This shift has been associated with an expanding welfare state and left-wing dominance. However, the pattern is far from uniform and while some left-wing governments indeed expanded consumption taxation, others did not. This paper seeks to explain why, by exploring how experts infl uenced post-war tax policy in Britain and Sweden. Experts infl uence is crucial when explaining how the left began to see consumption tax not as a threat but as an opportunity. Interestingly, the infl uence of experts such as Nicholas Kaldor in Britain was different from the impact of Swedish experts (e.g. Gösta Rehn). I make the argument that the impact of expert advice is contingent on the political risks facing governments. The low risks facing the Swedish Left made it more amenable to the advantages of broad-based sales taxes, while the high-risk environment in Britain made Labour reject these ideas. Keywords: taxation, expert infl uence, economic history, political economy JEL classifi cation indices: H20, H23, H61, N44 Per F. Andersson, Doctoral student at the Department of Political Science, Lund University, Swe- den. E-mail: [email protected] 0001-6373 © 2017 Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest 80 PER F. ANDERSSON 1. INTRODUCTION Parties to the Left have traditionally favoured progressive taxes on income and wealth over regressive taxes on consumption.1 However, during the decades fol- lowing World War II, this attitude changed, and countries with a strong Left be- came associated with a heavy reliance on consumption taxes (e.g. -

The Impact of the Reformation on the Formation of Mentality and the Moral Landscape in the Nordic Countries1 VEIKKO ANTTONEN University of Turku

The impact of the Reformation on the formation of mentality and the moral landscape in the Nordic countries1 VEIKKO ANTTONEN University of Turku Abstract Along with the Lutheran world the Nordic countries celebrated the five hundredth anniversary of the Reformation on 31st October 2017. In this article I shall examine the impact of Luther’s reform on the formation of mentality and the moral landscape in the Nordic coun- tries. Special reference is made to the impact of Lutheranism on the indigenous Sámi culture, a topic which has been explored extensively by Håkan Rydving, the expert in Sámi language and religion. Keywords: Reformation, Martin Luther, Nordic countries, national identity, mentality, Sámi, Laestadianism The Protestant Reformation has played an extremely important role in the historical development of Europe during the last five hundred years. No other event in European history has received such widespread attention. It took place in the obscure fortress and university town of Wittenberg on 31st October 1517. A single hand-written text containing ninety-five theses against the beliefs and practices of the medieval Catholic Church opened a new era in European history. The well-known story tells us that the Augus- tinian monk and university professor Martin Luther came to his theological moment by the single act of nailing his ninety-five theses to the door of the Castle Church of Wittenberg (Roper 2016). Whether Luther used a nail to pin his theses on the door is a myth which cannot be verified. As Lyndal Roper writes in her biographical study of Martin Luther, the initial inten- tion of the Reformer was not to spark a religious revolution, but to start an academic debate (Roper 2016, 2). -

Chapter One: the Origins of the Great Transformation (1879-1900)

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA Constructing the People’s Home: The Political and Economic Origins and Early Development of the “Swedish Model” (1879-1976) A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the Department of Politics School of Arts and Sciences Of The Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy © Copyright All Rights Reserved By Josiah R. Baker Washington, DC 2011 Constructing the People’s Home: The Political and Economic Origins and Early Development of the “Swedish Model” (1879-1976) Josiah R. Baker Director: James P. O’Leary, Ph.D. When Marquis Childs published his book The Middle Way in 1936, he laid the foundation that inspired the quest for an efficient welfare state. The Folkhemmet, or “people’s home,” initiated by the Social Democrats symbolized the “Swedish Way” and resulted in a generous, redistributive welfare state system. By the early 1970s, experts marveled at Sweden’s performance because the Swedish model managed to produce the second-wealthiest economy as measured by per capita GDP with virtually no cyclical unemployment. This dissertation demonstrates that capitalist and pre-industrial cultural forces dominated Swedish economic policy development throughout the years that the Social Democrats constructed Folkhemmet. The Swedish economy operated as a variety of capitalism that infused unique traditional cultural characteristics into a “feudal capitalism.” The system was far more market-oriented, deregulated, and free from direct government ownership or control than most assumed then or now. A process of negotiation and reason, mixed with pragmatism and recognition of valuing opportunity over principles, drove Swedish modernization. -

Jakob Gustavsson the POLITICS of FOREIGN POLICY CHANGE

Jakob Gustavsson Lund Political Studies 105 THE POLITICS OF FOREIGN POLICY CHANGE EXPLAINING THE SWEDISH REORIENTATION ON EC MEMBERSHIP THE POLITICS OF FOREIGN POLICY CHANGE Explaining the Swedish Reorientation on EC Membership THE POLITICS OF FOREIGN POLICY CHANGE The 1990s has been characterized by profound changes in world affairs. While numerous states have chosen to redirect their foreign policy orientations, political scientists have been slow to study how such processes take place. Drawing on the limited earlier research that does exist in this field, this study presents an alternative explanatory model of foreign policy change, arguing that a new policy is adopted when changes in fundamental structural conditions coincide with strategic political agency, and a crisis of some kind. The model is applied to the Swedish government’s decision in October 1990 to restructure its relationship to the West European integra- tion process and advocate an application for EC membership. As such it constitutes the first in-depth study of what is perhaps the most important political decision in Swedish postwar history. The author provides a thorough examination of the prevailing political and economic conditions, as well as an insightful analysis of the government’s internal decision-making process, emphasizing in particular the strategic behavior of Prime Minister Ingvar Carlsson. Lund University Press Chartwell-Bratt Ltd Jakob Box 141, SE-221 00 Lund, Sweden Old Orchard, Bickley Road, Gustavsson Art. nr. Bromley, Kent BR1 2NE ISSN England ISBN -

Med Folkhemmet Som Käpp Och Svärd - En Historisk Studie Av Hur Folkhemmet Används Som Politiskt Maktredskap Av Socialdemokraterna Och Sverigedemokraterna

Lunds universitet Historiska institutionen HISK37 Seminarieledare: Helen Persson Handledare: Klas-Göran Karlsson VT 2020 ZOOM Med folkhemmet som käpp och svärd - En historisk studie av hur folkhemmet används som politiskt maktredskap av Socialdemokraterna och Sverigedemokraterna Jakob Sivhed Innehållsförteckning 1 Inledning.................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Presentation av ämnet ....................................................................................... 1 1.2 Syfte och frågeställning .................................................................................... 2 1.2.1 Syfte .......................................................................................................... 2 1.2.2 Frågeställning ............................................................................................ 2 1.2.3 Fortsatt disposition av uppsatsen .............................................................. 2 1.3 Forskningsöversikt/forskningsläge ................................................................... 2 1.4 Metod och källmaterial (urval, avgränsningar och tillvägagångssätt) .............. 4 1.4.1 Metod ........................................................................................................ 4 1.4.2 Källmaterial och avgränsningar ................................................................ 5 1.5 Teoretiska perspektiv (analytisk ram) ............................................................... 7 2 Historisk bakgrund -

Speech by Mrs. Lisbet Palme on the 2014 Olof Palme Prize Ceremony

Speech by Mrs. Lisbet Palme on the 2014 Olof Palme Prize Ceremony, January 30, 2015 Today we are celebrating the recipient of the 2014 Olof Palme Prize, Professor Xu Youyu, for his international and prominent research focusing on areas of importance to the quest for peace in a broad context. At the same time we are struck by a tsunami wave of knowledge about the oppressed, tortured, hunted, humiliated people around our common globe. Thousands of lives are lost under horrendous circumstances. Xu Youyu, I will try to catch a moment of joy for freedom. Let us go back fifty years. In 1965 Olof Palme was Advisory Minister to the Prime minister of Sweden Mr. Tage Erlander who was Prime Minister of Sweden for 23 years. Mr. Tage Erlander and his wife Aina were invited to an official visit to the Soviet Union. Olof was travelling with the Prime Minister and I was invited to accompany Aina Erlander. In Moscow we entered the limousine taking us to the guesthouse. Tage Erlander talked loudly with gestures about his political intentions. Aina Erlander and myself tried to calm down this peaceful Prime Minister but he asked “Where are bugging equipment? Tell me! Tell me! For once I will get my message out.” And he smiled. I will send you two quotations as a message from Olof, connected to your work; in politics and democracy. Already in 1964, Olof Palme held a speech at the Social Democratic Youth of Sweden Congress. And he said: “Politics is to want something. Social Democratic politics is to want change, because change holds out the prospect of improvements, offers food for the imagination and encourages initiative, dreams and visions.” Some ten years later in 1975, then as a Prime Minister of Sweden, Olof held a speech at the Social Democratic Party Congress in Stockholm.