Cabinet Reshuffles and Prime Ministerial Power

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliography

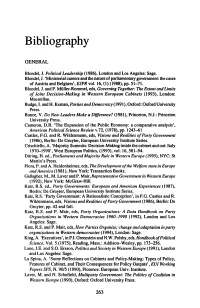

Bibliography GENERAL Blonde!, J. Political Leadership (1986), London and Los Angeles: Sage. Blonde!, J. 'Ministerial careers and the nature of parliamentary government: the cases of Austria and Belgium', EJPR vol. 16, (l) (1988), pp. 51-71. Blonde!, J. and F. MUller-Rommel, eds, Governing Together: Tile Extent and Limits of Joint Decision-Making in Western European Cabinets (1993), London: Macmillan. Budge, I. and H. Kernan, Parties and Democracy ( 1991 ), Oxford: Oxford University Press. Bunce, V. Do New Leaders Make a Difference? (1981), Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. Cameron, D.R. 'The Expansion of the Public Economy: a comparative analysis', American Political Science Review v.12, (1978), pp. 1243-61 Castles, P.O. and R. Wilden mann, eds, Visions and Realities of Party Government (1986), Berlin: De Gruyter, European University Institute Series. Criscitiello, A. 'Majority Summits: Decision-Making inside the cabinet and out: Italy 1970-1990', West European Politics, (1993), vol. 16, 581-94. Dt>ring, H. ed., Parliaments and Majority Rule in Western Europe (1995), NYC: St Martin's Press. Flora, P. and A. Heidenheimer, eds, The Development ofthe Welfare state in Europe and America (1981), New York: Transaction Books. Gallagher, M., M. Laver and P. Mair, Representative Government in Western Europe (1992), New York: McGraw-Hill. Katz, R.S. ed., Party Govemments: European and American Expe1·iences (1987), Berlin: De Gruyter, European University Institute Series. Katz, R.S. 'Party Government: A Rationalistic Conception', in F. G. Castles and R. Wildenmann, eds, Visions and Realities of Party Government (1986), Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 42 and foil. Katz, R.S. -

The Olof Palme International Center

About The Olof Palme International Center The Olof Palme International Center works with international development co-operation and the forming of public opinion surrounding international political and security issues. The Palme Center was established in 1992 by the Swedish Social Democratic Party, the Trade Union Confederation (LO) and the Cooperative Union (KF). Today the Palme Center has 28 member organizations within the labour movement. The centre works in the spirit of the late Swedish Prime Minister Olof Palme, reflected by the famous quotation: "Politics is wanting something. Social Democratic politics is wanting change." Olof Palme's conviction that common security is created by co-operation and solidarity across borders, permeates the centre's activities. The centre's board is chaired by Lena Hjelm-Wallén, former foreign minister of Sweden. Viola Furubjelke is the centre's Secretary General, and Birgitta Silén is head of development aid. There are 13 members of the board, representing member organisations. The commitment of these member organisations is the core of the centre's activities. Besides the founding organisations, they include the Workers' Educational Association, the tenants' movement, and individual trade unions. As popular movements and voluntary organisations , they are represented in all Swedish municipalities and at many workplaces. An individual cannot be a member of the Palme Center, but the member organisations together have more than three million members. In Sweden, the centre carries out comprehensive information and opinion-forming campaigns on issues concerning international development, security and international relations. This includes a very active schedule of seminars and publications, both printed and an e-mail newsletter. -

(American Swedish News Exchange, New York, NY), 1920S-1990

Allan Kastrup collection (American Swedish News Exchange, New York, N.Y), 1920s-1990 Size: 19.25 linear feet, 28 boxes Acquisition: The collection was donated to SSIRC in 1990 and 1991. Access: The collection is open for research and a limited amount to copies can be requested via mail. Processed by: Christina Johansson Control Num.: SSIRC MSS P: 308 Historical Sketch The American-Swedish News Exchange was established by the Sweden-America Foundation in Stockholm in 1921 and the agency opened its office in New York City in 1922. ASNE's main purpose was to increase and broaden the general knowledge about Sweden and to provide the American press with news on cultural, economic and political developments in Sweden. The agency also had the primary responsibility for publicity campaigns during Swedish official visits to the United States, such as the Crown Prince Gustav Adolf's visit in 1926, the New Sweden Tercentenary in 1938, and the Swedish Pioneer Centennial in 1948. Between 1926 and 1946, ASNE was under the leadership of Naboth Hedin. Hedin increased the visibility of Sweden in the American press immensely, wrote countless of articles on Sweden, and co-edited with Adolph H. Benson Swedes in America: 1638-1938. Hedin was also instrumental in assisting many American writers with advice and information about Sweden; including Marquis W. Childs in his widely read and circulated work Sweden the Middle Way, first published in 1936. Allan Kastrup assumed the leadership of ASNE in 1946. He held this position until his retirement in 1964, at which time ASNE ceased to exist and its responsibilities were assumed by the Swedish Information Service. -

Government Formation and Minister Turnover in Presidential Cabinets

Review Copy – Not for Redistribution Marcelo Camerlo - University of Lisbon - 21/04/2020 Government Formation and Minister Turnover in Presidential Cabinets Portfolio allocation in presidential systems is a central tool that presidents use to deal with changes in the political and economic environment. Yet, we still have much to learn about the process through which ministers are selected and the reasons why they are replaced in presidential systems. This book offers the most comprehensive, cross- national analysis of portfolio allocation in the Americas to date. In doing so, it contributes to the development of theories about portfolio allocation in presidential systems. Looking specifi- cally at how presidents use portfolio allocation as part of their wider political strategy, it examines eight country case studies, within a carefully developed analytical framework and cross- national comparative analysis from a common dataset. The book includes cases studies of portfolio allocation in Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, the United States, Peru and Uruguay, and covers the period between the transition to democracy in each country up until 2014. This book will be of key interest to scholars and students of political elites, executive politics, Latin Amer ican politics and more broadly comparative politics. Marcelo Camerlo is Researcher at the Institute of Social Sciences of the Uni- versity of Lisbon (ICS- UL), Portugal. Cecilia Martínez-Gallardo is Associate Professor in the Department of Polit- ical Science at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, USA. Review Copy – Not for Redistribution Marcelo Camerlo - University of Lisbon - 21/04/2020 Routledge Research on Social and Political Elites Edited by Keith Dowding Australian National University and Patrick Dumont University of Luxembourg Who are the elites that run the world? This series of books analyses who the elites are, how they rise and fall, the networks in which they operate and the effects they have on our lives. -

![Arxiv:2106.01515V1 [Cs.LG] 3 Jun 2021 Tor Representations of Entities and Relations in a KG](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4165/arxiv-2106-01515v1-cs-lg-3-jun-2021-tor-representations-of-entities-and-relations-in-a-kg-1054165.webp)

Arxiv:2106.01515V1 [Cs.LG] 3 Jun 2021 Tor Representations of Entities and Relations in a KG

Question Answering Over Temporal Knowledge Graphs Apoorv Saxena Soumen Chakrabarti Partha Talukdar Indian Institute of Science Indian Institute of Technology Google Research Bangalore Bombay India [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract time intervals as well. These temporal scopes on facts can be either automatically estimated (Taluk- Temporal Knowledge Graphs (Temporal KGs) extend regular Knowledge Graphs by provid- dar et al., 2012) or user contributed. Several such ing temporal scopes (e.g., start and end times) Temporal KGs have been proposed in the literature, on each edge in the KG. While Question An- where the focus is on KG completion (Dasgupta swering over KG (KGQA) has received some et al. 2018; Garc´ıa-Duran´ et al. 2018; Leetaru and attention from the research community, QA Schrodt 2013; Lacroix et al. 2020; Jain et al. 2020). over Temporal KGs (Temporal KGQA) is a The task of Knowledge Graph Question Answer- relatively unexplored area. Lack of broad- coverage datasets has been another factor lim- ing (KGQA) is to answer natural language ques- iting progress in this area. We address this tions using a KG as the knowledge base. This is challenge by presenting CRONQUESTIONS, in contrast to reading comprehension-based ques- the largest known Temporal KGQA dataset, tion answering, where typically the question is ac- clearly stratified into buckets of structural com- companied by a context (e.g., text passage) and plexity. CRONQUESTIONS expands the only the answer is either one of multiple choices (Ra- known previous dataset by a factor of 340×. jpurkar et al., 2016) or a piece of text from the We find that various state-of-the-art KGQA methods fall far short of the desired perfor- context (Yang et al., 2018). -

PM Modi Rejigs Cabinet

PM Modi Rejigs Cabinet July 9, 2021 In a major shake up of his Council of Ministers almost midway through his second term, Prime Minister Narendra Modi oversaw the swearing-in of 43 Ministers (new and seven promotions to Cabinet rank) and dropped 12 Ministers (seven Cabinet and five Ministers of State) In news: Cabinet reshuffle attempts inclusion, political messaging Placing it in syllabus: Governance Dimensions What is Cabinet Reshuffle and How is it done? Minister : Appointment, Functions and Powers What is a Cabinet? Types of Ministers Difference between Cabinet and Council of Ministers Constitutional Position of both Content: What is Cabinet Reshuffle and How is it done? In a cabinet reshuffle or shuffle a head of government rotates or changes the composition of ministers in their cabinet, or when the Head of State changes the head of government and a number of ministers. Cabinet reshuffles happen in parliamentary systems for a variety of reasons. Periodically, smaller reshuffles are needed to replace ministers who have resigned, retired or died. Reshuffles are also a way for a premier to “refresh” the government, often in the face of poor polling numbers; remove poor performers; and reward supporters and punish others. Minister : Appointment, Functions and Powers The Government of India exercises its executive authority through a number of government ministries or departments of state. A ministry is composed of employed officials, known as civil servants, and is politically accountable through a minister. Two articles – Article 74 and Article 75 of the Indian Constitution deal with the Council of Ministers. Appointment: Article 75 mentions the following things: They are appointed by the President on the advice of Prime Minister They along with the Prime Minister of India form 15% of the total strength of the lower house i.e. -

The Corporate Analogy and the Legitimacy of Promoting Sweden Abroad in the 1960S

chapter 6 A Total Image Deconstructed: The Corporate Analogy and the Legitimacy of Promoting Sweden Abroad in the 1960s Nikolas Glover In the spring of 1967, an exhibited print by the well-known leftist artist Carl Johan de Geer was confiscated by the police in Stockholm. It depicted a burning Swedish flag, capped by three slogans: “Dishonour the flag,” “Betray the Fatherland,” “Dare to be non-nationalist.” The flag itself had one word sprawled across it: Kuken, slang for penis. The motif was judged to be in breach of the Swedish constitution (by defiling the flag) and de Geer was fined in court.1 The episode sets the historic scene for this chapter. In the second half of the 1960s, self-proclaimed anti-patriotic sentiments like those voiced by de Geer were gain- ing widespread popularity among artists-cum-activists and within the growing movements of the New Left.2 Meanwhile, publicly funded “Sweden-information abroad” was expanding in scope and ambition.3 This chapter focuses on the rela- tionship between these two developments, showing how practitioners in the field of Sweden-information navigated between the imperatives of efficient communication and democratic legitimacy. At the heart of this challenge lay the need to manage the diverging demands of the government’s foreign policy objec- tives, the export industry’s commercial interests, and a politically active cultural scene that was insisting that it should not have to cooperate with either. Managing Diverging Demands In many respects, representing Sweden abroad in the early 1960s was a thankful task: affluent, ambitiously reformist and technologically advanced, the country 1 “Konsten att göra uppror,” Svenska Dagbladet, 2 December 2007. -

France: Government Reshuffle

France: Government reshuffle Standard Note: SN06973 Last updated: 4 September 2014 Author: Rob Page Section International Affairs and Defence Section Manuel Valls, the Prime Minister of France, has reshuffled his Cabinet following criticism of the Government’s austerity policies by Arnaud Montebourg, the Economy Minister. Montebourg’s place in the Cabinet has been taken by Emmanuel Macron, a leading pro- business figure. This note explains the events leading to the reshuffle, and provides an overview of how the new cabinet has been received. This information is provided to Members of Parliament in support of their parliamentary duties and is not intended to address the specific circumstances of any particular individual. It should not be relied upon as being up to date; the law or policies may have changed since it was last updated; and it should not be relied upon as legal or professional advice or as a substitute for it. A suitably qualified professional should be consulted if specific advice or information is required. This information is provided subject to our general terms and conditions which are available online or may be provided on request in hard copy. Authors are available to discuss the content of this briefing with Members and their staff, but not with the general public. Contents 1 Introduction 3 2 Political background 3 3 Reshuffle 4 4 Reaction 5 2 1 Introduction Manuel Valls, the Prime Minister of France, has reshuffled his Cabinet following criticism of the Government’s austerity policies by Arnaud Montebourg, the Economy Minister. Montebourg’s place in the Cabinet has been taken by Emmanuel Macron, a leading pro- business figure. -

The Impact of Experts on Tax Policy in Post-War Britain and Sweden

Acta Oeconomica, Vol. 67 (S), pp. 79–96 (2017) DOI: 10.1556/032.2017.67.S.7 THE IMPACT OF EXPERTS ON TAX POLICY IN POST-WAR BRITAIN AND SWEDEN Per F. ANDERSSON During the decades after World War II, countries began shifting taxation from income to con- sumption. This shift has been associated with an expanding welfare state and left-wing dominance. However, the pattern is far from uniform and while some left-wing governments indeed expanded consumption taxation, others did not. This paper seeks to explain why, by exploring how experts infl uenced post-war tax policy in Britain and Sweden. Experts infl uence is crucial when explaining how the left began to see consumption tax not as a threat but as an opportunity. Interestingly, the infl uence of experts such as Nicholas Kaldor in Britain was different from the impact of Swedish experts (e.g. Gösta Rehn). I make the argument that the impact of expert advice is contingent on the political risks facing governments. The low risks facing the Swedish Left made it more amenable to the advantages of broad-based sales taxes, while the high-risk environment in Britain made Labour reject these ideas. Keywords: taxation, expert infl uence, economic history, political economy JEL classifi cation indices: H20, H23, H61, N44 Per F. Andersson, Doctoral student at the Department of Political Science, Lund University, Swe- den. E-mail: [email protected] 0001-6373 © 2017 Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest 80 PER F. ANDERSSON 1. INTRODUCTION Parties to the Left have traditionally favoured progressive taxes on income and wealth over regressive taxes on consumption.1 However, during the decades fol- lowing World War II, this attitude changed, and countries with a strong Left be- came associated with a heavy reliance on consumption taxes (e.g. -

Portfolio Allocation As the President's Calculations: Loyalty, Copartisanship, and Political Context in South Korea

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repository@Nottingham Portfolio Allocation as the President's Calculations: Loyalty, Copartisanship, and Political Context in South Korea Don S. Lee University of Nottingham [email protected] Accepted for publication in the Journal of East Asian Studies on 22 February 2018 Abstract How do the president's calculations in achieving policy goals shape the allocation of cabinet portfolios? Despite the growing literature on presidential cabinet appointments, this question has barely been addressed. I argue that cabinet appointments are strongly affected not only by presidential incentives to effectively deliver their key policy commitments but also by their interest in having their administration maintain strong political leverage. Through an analysis of portfolio allocations in South Korea after democratization, I demonstrate that the posts wherein ministers can influence the government's overall reputation typically go to nonpartisan professionals ideologically aligned with presidents, while the posts wherein ministers can exert legislators' influence generally go to senior copartisans. My findings highlight a critical difference in presidential portfolio allocation from parliamentary democracies, where key posts tend to be reserved for senior parliamentarians from the ruling party. Key Words: President, Presidential System, Minister, Cabinet Appointment, Portfolio Allocation, South Korea, East Asia 1 Existing research on cabinet formation in presidential systems has offered key insights on the chief executive's appointment strategy. According to the literature, presidents with limited policy making power tend to form a cabinet with more partisan ministers in order to reinforce support for their policy program (Amorim Neto 2006). -

The Impact and Effectiveness of Ministerial Reshuffles

House of Commons Political and Constitutional Reform Committee The impact and effectiveness of ministerial reshuffles Second Report of Session 2013–14 Volume I: Report, together with formal minutes and oral evidence Written evidence is contained in Volume II, available on the Committee website at www.parliament.uk/pcrc Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 13 June 2013 HC 255 [Incorporating HC 707-i to vii, Session 2012-13] Published on 14 June 2013 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 The Political and Constitutional Reform Committee The Political and Constitutional Reform Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to consider political and constitutional reform. Current membership Mr Graham Allen MP (Labour, Nottingham North) (Chair) Mr Christopher Chope MP (Conservative, Christchurch) Paul Flynn (Labour, Newport West) Sheila Gilmore MP (Labour, Edinburgh East) Andrew Griffiths MP (Conservative, Burton) Fabian Hamilton MP, (Labour, Leeds North East) Simon Hart MP (Conservative, Camarthen West and South Pembrokeshire) Tristram Hunt MP (Labour, Stoke on Trent Central) Mrs Eleanor Laing MP (Conservative, Epping Forest) Mr Andrew Turner MP (Conservative, Isle of Wight) Stephen Williams MP (Liberal Democrat, Bristol West) Powers The Committee’s powers are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in Temporary Standing Order (Political and Constitutional Reform Committee). These are available on the Internet via http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm/cmstords.htm. Publication The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. All publications of the Committee (including press notices) are on the internet at www.parliament.uk/pcrc. -

Post-Communist Romania: a Peculiar Case of Divided Government Manolache, Cristina

www.ssoar.info Post-communist Romania: a peculiar case of divided government Manolache, Cristina Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Manolache, C. (2013). Post-communist Romania: a peculiar case of divided government. Studia Politica: Romanian Political Science Review, 13(3), 427-440. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-448327 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de Post-Communist Romania 427 Post-Communist Romania A Peculiar Case of Divided Government CRISTINA MANOLACHE If for the most part of its post-communist history, Romania experienced a form of unified government based on political coalitions and alliances which resulted in conflictual relations between the executive and the legislative and even among the dualist executive itself, it should come as no surprise that the periods of divided government are marked by strong confrontations which have culminated with two failed suspension attempts. The main form of divided government in Romania is that of cohabitation, and it has been experienced only twice, for a brief period of time: in 2007-2008 under Prime-Minister Călin Popescu Tăriceanu of the National Liberal Party and again, starting May 2012, under Prime Minister Victor Ponta of the Social Democratic Party.