Neutrality and Solidarity in Nordic Humanitarian Action

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide to the Victor G. Reuther Papers LP000002BVGR

*XLGHWRWKH9LFWRU*5HXWKHU3DSHUV /3B9*5 7KLVILQGLQJDLGZDVSURGXFHGXVLQJ$UFKLYHV6SDFHRQ0DUFK (QJOLVK 'HVFULELQJ$UFKLYHV$&RQWHQW6WDQGDUG :DOWHU35HXWKHU/LEUDU\ &DVV$YHQXH 'HWURLW0, 85/KWWSVUHXWKHUZD\QHHGX Guide to the Victor G. Reuther Papers LP000002_VGR Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 4 History ............................................................................................................................................................ 4 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 5 Arrangement ................................................................................................................................................... 7 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 8 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 9 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 9 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 9 Series I: Reuther Brothers, -

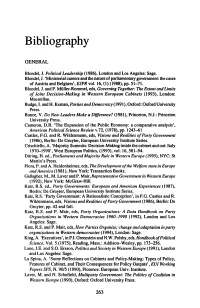

Bibliography

Bibliography GENERAL Blonde!, J. Political Leadership (1986), London and Los Angeles: Sage. Blonde!, J. 'Ministerial careers and the nature of parliamentary government: the cases of Austria and Belgium', EJPR vol. 16, (l) (1988), pp. 51-71. Blonde!, J. and F. MUller-Rommel, eds, Governing Together: Tile Extent and Limits of Joint Decision-Making in Western European Cabinets (1993), London: Macmillan. Budge, I. and H. Kernan, Parties and Democracy ( 1991 ), Oxford: Oxford University Press. Bunce, V. Do New Leaders Make a Difference? (1981), Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. Cameron, D.R. 'The Expansion of the Public Economy: a comparative analysis', American Political Science Review v.12, (1978), pp. 1243-61 Castles, P.O. and R. Wilden mann, eds, Visions and Realities of Party Government (1986), Berlin: De Gruyter, European University Institute Series. Criscitiello, A. 'Majority Summits: Decision-Making inside the cabinet and out: Italy 1970-1990', West European Politics, (1993), vol. 16, 581-94. Dt>ring, H. ed., Parliaments and Majority Rule in Western Europe (1995), NYC: St Martin's Press. Flora, P. and A. Heidenheimer, eds, The Development ofthe Welfare state in Europe and America (1981), New York: Transaction Books. Gallagher, M., M. Laver and P. Mair, Representative Government in Western Europe (1992), New York: McGraw-Hill. Katz, R.S. ed., Party Govemments: European and American Expe1·iences (1987), Berlin: De Gruyter, European University Institute Series. Katz, R.S. 'Party Government: A Rationalistic Conception', in F. G. Castles and R. Wildenmann, eds, Visions and Realities of Party Government (1986), Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 42 and foil. Katz, R.S. -

Constructing Labour Regionalism in Europe and the Americas, 1920S–1970S*

IRSH 58 (2013), pp. 39–70 doi:10.1017/S0020859012000752 r 2012 Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis Constructing Labour Regionalism in Europe and the Americas, 1920s–1970s* M AGALY R ODRI´ GUEZ G ARCI´ A Vrije Universiteit Brussel/Research Foundation Flanders (FWO) Pleinlaan 2-5B 407d, 1050 Brussels, Belgium E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT: This article provides an analysis of the construction of labour regionalism between the 1920s and 1970s. By means of a comparative examination of the supranational labour structures in Europe and the Americas prior to World War II and of the decentralized structure of the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions (ICFTU), I attempt to defend the argument that regionalism was a labour leaders’ construct that responded to three issues: the quest for power among the largest trade-union organizations within the international trade-union movement; mutual distrust between labour leaders of large, middle-sized, and small unions from different regions; and (real or imaginary) common interests among labour leaders from the same region. These push-and-pull factors led to the construction of regional labour identifications that emphasized ‘‘otherness’’ in the world of international labour. A regional labour identity was intended to supplement, not undermine, national identity. As such, this study fills a lacuna in the scholarly literature on international relations and labour internationalism, which has given only scant attention to the regional level of international labour organization. This article provides a comparative analysis of the construction of regional identifications among labour circles prior to World War II, and to the formalization of the idea of regionalism within the International Con- federation of Free Trade Unions (ICFTU1) after 1949. -

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS STOCKHOLMIENSIS Stockholm Studies in Economic History 51

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS STOCKHOLMIENSIS Stockholm Studies in Economic History 51 Fordismens kris och löntagarfonder i Sverige Ilja Viktorov Stockholm University © Ilja Viktorov, Stockholm 2006 ISSN 0346-8305 ISBN 91-85445-51-7 Typesetting: Intellecta Docusys Printed in Sweden by Intellecta Docusys, Västra Frölunda, 2006 Distributor: Stockholm University Library Omslagsbild: Demonstrationen mot löntagarfonder den 4 oktober 1983, Stockholm (© foto från Svenskt Näringslivs arkiv, Centrum för Näringslivshistoria) Till min Mamma Посвящается моей маме Innehåll Förkortningar .............................................................................x Erkänsla / Acknowledgments...................................................11 Kapitel 1. Inledning ..................................................................15 Bakgrund .......................................................................................................................15 Syfte...............................................................................................................................19 Tidigare forskning..........................................................................................................19 Teori och begrepp. Den fordistiska debattens tre riktningar .........................................25 Metod.............................................................................................................................30 Avgränsning...................................................................................................................30 -

The Olof Palme International Center

About The Olof Palme International Center The Olof Palme International Center works with international development co-operation and the forming of public opinion surrounding international political and security issues. The Palme Center was established in 1992 by the Swedish Social Democratic Party, the Trade Union Confederation (LO) and the Cooperative Union (KF). Today the Palme Center has 28 member organizations within the labour movement. The centre works in the spirit of the late Swedish Prime Minister Olof Palme, reflected by the famous quotation: "Politics is wanting something. Social Democratic politics is wanting change." Olof Palme's conviction that common security is created by co-operation and solidarity across borders, permeates the centre's activities. The centre's board is chaired by Lena Hjelm-Wallén, former foreign minister of Sweden. Viola Furubjelke is the centre's Secretary General, and Birgitta Silén is head of development aid. There are 13 members of the board, representing member organisations. The commitment of these member organisations is the core of the centre's activities. Besides the founding organisations, they include the Workers' Educational Association, the tenants' movement, and individual trade unions. As popular movements and voluntary organisations , they are represented in all Swedish municipalities and at many workplaces. An individual cannot be a member of the Palme Center, but the member organisations together have more than three million members. In Sweden, the centre carries out comprehensive information and opinion-forming campaigns on issues concerning international development, security and international relations. This includes a very active schedule of seminars and publications, both printed and an e-mail newsletter. -

(American Swedish News Exchange, New York, NY), 1920S-1990

Allan Kastrup collection (American Swedish News Exchange, New York, N.Y), 1920s-1990 Size: 19.25 linear feet, 28 boxes Acquisition: The collection was donated to SSIRC in 1990 and 1991. Access: The collection is open for research and a limited amount to copies can be requested via mail. Processed by: Christina Johansson Control Num.: SSIRC MSS P: 308 Historical Sketch The American-Swedish News Exchange was established by the Sweden-America Foundation in Stockholm in 1921 and the agency opened its office in New York City in 1922. ASNE's main purpose was to increase and broaden the general knowledge about Sweden and to provide the American press with news on cultural, economic and political developments in Sweden. The agency also had the primary responsibility for publicity campaigns during Swedish official visits to the United States, such as the Crown Prince Gustav Adolf's visit in 1926, the New Sweden Tercentenary in 1938, and the Swedish Pioneer Centennial in 1948. Between 1926 and 1946, ASNE was under the leadership of Naboth Hedin. Hedin increased the visibility of Sweden in the American press immensely, wrote countless of articles on Sweden, and co-edited with Adolph H. Benson Swedes in America: 1638-1938. Hedin was also instrumental in assisting many American writers with advice and information about Sweden; including Marquis W. Childs in his widely read and circulated work Sweden the Middle Way, first published in 1936. Allan Kastrup assumed the leadership of ASNE in 1946. He held this position until his retirement in 1964, at which time ASNE ceased to exist and its responsibilities were assumed by the Swedish Information Service. -

![Arxiv:2106.01515V1 [Cs.LG] 3 Jun 2021 Tor Representations of Entities and Relations in a KG](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4165/arxiv-2106-01515v1-cs-lg-3-jun-2021-tor-representations-of-entities-and-relations-in-a-kg-1054165.webp)

Arxiv:2106.01515V1 [Cs.LG] 3 Jun 2021 Tor Representations of Entities and Relations in a KG

Question Answering Over Temporal Knowledge Graphs Apoorv Saxena Soumen Chakrabarti Partha Talukdar Indian Institute of Science Indian Institute of Technology Google Research Bangalore Bombay India [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract time intervals as well. These temporal scopes on facts can be either automatically estimated (Taluk- Temporal Knowledge Graphs (Temporal KGs) extend regular Knowledge Graphs by provid- dar et al., 2012) or user contributed. Several such ing temporal scopes (e.g., start and end times) Temporal KGs have been proposed in the literature, on each edge in the KG. While Question An- where the focus is on KG completion (Dasgupta swering over KG (KGQA) has received some et al. 2018; Garc´ıa-Duran´ et al. 2018; Leetaru and attention from the research community, QA Schrodt 2013; Lacroix et al. 2020; Jain et al. 2020). over Temporal KGs (Temporal KGQA) is a The task of Knowledge Graph Question Answer- relatively unexplored area. Lack of broad- coverage datasets has been another factor lim- ing (KGQA) is to answer natural language ques- iting progress in this area. We address this tions using a KG as the knowledge base. This is challenge by presenting CRONQUESTIONS, in contrast to reading comprehension-based ques- the largest known Temporal KGQA dataset, tion answering, where typically the question is ac- clearly stratified into buckets of structural com- companied by a context (e.g., text passage) and plexity. CRONQUESTIONS expands the only the answer is either one of multiple choices (Ra- known previous dataset by a factor of 340×. jpurkar et al., 2016) or a piece of text from the We find that various state-of-the-art KGQA methods fall far short of the desired perfor- context (Yang et al., 2018). -

Cabinet Reshuffles and Prime Ministerial Power

Cabinet Reshuffles and Prime Ministerial Power Jörgen Hermansson and Kåre Vernby ***VERY PRELIMINARY “IDEAS-PAPER”*** Abstract This paper contains some ideas about how to transform a paper we wrote together in Swedish for an anthology on Swedish governments 1917-2009. There, we point out that reshuffles are problematic when used as an indicator of prime-ministerial power/dominance over the cabinet. In the future, we wish to expand our critique. In this “ideas paper”, however, we only briefly outline our critique. We will argue that there exist at least two problems inherent in using the frequency of reshuffles as an indicator of Prime-ministerial power over the cabinet. The first we call the “problem of proxying”, which arises because scholars implicitly use the frequency of reshuffles as a proxy for the political experience of the ministers surrounding the PM. Specifically, the frequency of reshuffles is thought to be inversely related to the political experience of ministers. The second problem we call the “problem of selection bias”, which arises because of the failure to properly specifying the possibility of a bi-directional causal relationship between prime-ministerial power and cabinet reshuffles. We will try to argue that these are serious problems for those who wish to use the frequency of cabinet reshuffles as a measure of prime ministerial using historical data and examples from the Swedish history with parliamentarism. 1 Introduction While the formation and collapse of cabinet governments has been a mainstay of political science for more than 50 years, the recent decade has seen a growing pre- occupation with cabinet reshuffles. -

Wori(Ers' Participation

Xto I 1 -/ )~ WORI(ERS' PARTICIPATION CHRISTER ASPLUND INSTITUTEOP!N9US TR! A1 APR Ca974 INTERNATIONAL CONFEDERATION OF FREE TRADE UNIONS BRUSSELS S~ome aspects of workers' participation: A survey prepared for the ICFTU by CHRISTER ASPLUND a member of the research staff of the Swedish Central Organisation of Salaried Employees (TCO) INTERNATIONAL CONFEDERATION OF FREE TRADE UNIONS - BRUSSELSWcM tT-7I2I ? INTERNATIONAL CONFEDERATION OF FREE TRADE UNIONS Rue Montagne aux Herbes Potageres, 37-41 - B - 1000 Brussels May 1972 Price: 50 p., $ 1.25 D/1972/0403/8 2 F O R E W O R D Although the term itself is relatively new, the idea behind " workers' participation" has roots going deep into the history of the labour move- ment. Reduced to its simplest form it is merely a question of how to secure a bigger say for the workers in the determination of the conditions governing their everyday working lives. In recent years, however, the growing concentration of production in ever bigger units and the increasing remoteness of the real centres of economic power, especially with the spread of huge multinational com- panies, have lent added urgency to the problem. In every country, whatever its political set-up may be, the worker- at the place of work - is most of the time up against a system which has little in common with democracy. However strong the trade union may be, most of the vital decisions about the organisation and tempo of production, investment, the distribution of profits, the use of manpower, training, promotion, hiring and firing, are still management prerogatives. -

Boycotts and Sanctions Against South Africa: an International History, 1946-1970

Boycotts and Sanctions against South Africa: An International History, 1946-1970 Simon Stevens Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2016 © 2016 Simon Stevens All rights reserved ABSTRACT Boycotts and Sanctions against South Africa: An International History, 1946-1970 Simon Stevens This dissertation analyzes the role of various kinds of boycotts and sanctions in the strategies and tactics of those active in the struggle against apartheid in South Africa. What was unprecedented about the efforts of members of the global anti-apartheid movement was that they experimented with so many ways of severing so many forms of interaction with South Africa, and that boycotts ultimately came to be seen as such a central element of their struggle. But it was not inevitable that international boycotts would become indelibly associated with the struggle against apartheid. Calling for boycotts and sanctions was a political choice. In the years before 1959, most leading opponents of apartheid both inside and outside South Africa showed little interest in the idea of international boycotts of South Africa. This dissertation identifies the conjuncture of circumstances that caused this to change, and explains the subsequent shifts in the kinds of boycotts that opponents of apartheid prioritized. It shows that the various advocates of boycotts and sanctions expected them to contribute to ending apartheid by a range of different mechanisms, from bringing about an evolutionary change in white attitudes through promoting the desegregation of sport, to weakening the state’s ability to resist the efforts of the liberation movements to seize power through guerrilla warfare. -

The Corporate Analogy and the Legitimacy of Promoting Sweden Abroad in the 1960S

chapter 6 A Total Image Deconstructed: The Corporate Analogy and the Legitimacy of Promoting Sweden Abroad in the 1960s Nikolas Glover In the spring of 1967, an exhibited print by the well-known leftist artist Carl Johan de Geer was confiscated by the police in Stockholm. It depicted a burning Swedish flag, capped by three slogans: “Dishonour the flag,” “Betray the Fatherland,” “Dare to be non-nationalist.” The flag itself had one word sprawled across it: Kuken, slang for penis. The motif was judged to be in breach of the Swedish constitution (by defiling the flag) and de Geer was fined in court.1 The episode sets the historic scene for this chapter. In the second half of the 1960s, self-proclaimed anti-patriotic sentiments like those voiced by de Geer were gain- ing widespread popularity among artists-cum-activists and within the growing movements of the New Left.2 Meanwhile, publicly funded “Sweden-information abroad” was expanding in scope and ambition.3 This chapter focuses on the rela- tionship between these two developments, showing how practitioners in the field of Sweden-information navigated between the imperatives of efficient communication and democratic legitimacy. At the heart of this challenge lay the need to manage the diverging demands of the government’s foreign policy objec- tives, the export industry’s commercial interests, and a politically active cultural scene that was insisting that it should not have to cooperate with either. Managing Diverging Demands In many respects, representing Sweden abroad in the early 1960s was a thankful task: affluent, ambitiously reformist and technologically advanced, the country 1 “Konsten att göra uppror,” Svenska Dagbladet, 2 December 2007. -

The Impact of Experts on Tax Policy in Post-War Britain and Sweden

Acta Oeconomica, Vol. 67 (S), pp. 79–96 (2017) DOI: 10.1556/032.2017.67.S.7 THE IMPACT OF EXPERTS ON TAX POLICY IN POST-WAR BRITAIN AND SWEDEN Per F. ANDERSSON During the decades after World War II, countries began shifting taxation from income to con- sumption. This shift has been associated with an expanding welfare state and left-wing dominance. However, the pattern is far from uniform and while some left-wing governments indeed expanded consumption taxation, others did not. This paper seeks to explain why, by exploring how experts infl uenced post-war tax policy in Britain and Sweden. Experts infl uence is crucial when explaining how the left began to see consumption tax not as a threat but as an opportunity. Interestingly, the infl uence of experts such as Nicholas Kaldor in Britain was different from the impact of Swedish experts (e.g. Gösta Rehn). I make the argument that the impact of expert advice is contingent on the political risks facing governments. The low risks facing the Swedish Left made it more amenable to the advantages of broad-based sales taxes, while the high-risk environment in Britain made Labour reject these ideas. Keywords: taxation, expert infl uence, economic history, political economy JEL classifi cation indices: H20, H23, H61, N44 Per F. Andersson, Doctoral student at the Department of Political Science, Lund University, Swe- den. E-mail: [email protected] 0001-6373 © 2017 Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest 80 PER F. ANDERSSON 1. INTRODUCTION Parties to the Left have traditionally favoured progressive taxes on income and wealth over regressive taxes on consumption.1 However, during the decades fol- lowing World War II, this attitude changed, and countries with a strong Left be- came associated with a heavy reliance on consumption taxes (e.g.