Uirginf Iqjiy V"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue 9 •Sports Lingo P

TheStudent photos by DeCloud Studios Miegian Volume 57 Issue 9 •Sports Lingo p. 15• Senior Edition •Departing Teachers p. 2• Seniors missing from mural (due to unavailability): May 2014 •One Acts p. 4•Senior pullout• Daniel Becker, Ryan Estrada, McKinley Johnson, Lucy Kraus Miegian N E W S Small but Mighty Five Stags Are Leaving the Herd News Car Raffle Tickets The total sold by the students was $21,085 for 60% of the $35,000 goal. The seniors brought in 35% of their goal, juniors 50% of their goal, sophomores 61% of their goal and freshmen 80% of theirs. The top sellers were Rachel Lavery with $300 and Tyler Pennell with Mike Bohaty- 26 years Paula Munro- 20 years Amy Lukert- 7 years Emily McGinnis- 3 years Fred Turner- 2 years $275. The winner of the car was the What did you teach or what was your role? Also, with what type of fondest memories come from the more relaxed student interactions in rehearsals, activities were you involved? lessons, at basketball games, or on a bus for a field trip.” Kincaid family, who donated it back to • Mike Bohaty- “My first two years I was associate principal and was in charge of • Fred Turner- “Beating St. Thomas Aquinas like a drum for the championship of the the school before it was purchased by the St. Thomas Aquinas Tournament, The relationships developed between my players discipline, attendance and athletics. The third year a ‘Director for Attendance’ was Belfield family. hired. I was in charge of half the discipline and attendance and had activities. -

An Interview with Amor Towles

THE 1511 South 1500 East Salt Lake City, UT 84105 InkslingerSpring Issue 2 019 801-484-9100 The Arc of History: A Gentleman in Moscow, Amor Towles An Interview with Amor Towles— A young Russian count is saved from He’ll be in SLC April 2! a Bolshevik bullet because of a pre- by Betsy Burton revolution pro-revolution poem. Given his aristocratic upbringing he can’t go I called Amor Towles to talk to him free. So what is a Communist Commit- about A Gentleman in Moscow, but be- tee of the Commissariat to do? Put this fore we started with questions he won- unsuspicious suspect under house arrest dered who I was and whether we hadn’t in the grand hotel in which he’s staying, of met before at some book dinner or course. A hotel that, like Count Alexan- other. Knowing how often he speaks in der Ilyich Rostov himself, is allowed to exist for secret reasons public, I was surprised he remembered. of state. Our Count is nothing if not creative, and it isn’t long We had met, I said. Had sat next to one before his courtly manners and charm create a constella- another at a breakfast—an American tion of comrades that will inhabit your heart: Nina, a child Booksellers event at which he was the who teaches him the fine art of spying; her daughter Sophia, keynote speaker a couple of years ago. I decades later; his old friend, the poet Mishka; the glamorous thought so, he said. After chatting for a actress, Anna Urbanova; the hotel staff… As witty, cosmopoli- few minutes, I asked my first question tan, and unflappable as the Scarlet Pimpernel on the outside, Amor Towles, who will be in SLC as kind and as thoughtful as Tolstoy’s Pierre Bezukhov on the which was, admittedly, longwinded. -

BTS) Official Twitter

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UKM Journal Article Repository 3L: The Southeast Asian Journal of English Language Studies – Vol 23(3): 67 – 80 http://doi.org/10.17576/3L-2017-2303-05 Korean-English Language Translational Action of K-Pop Social Media Content: A Case Study on Bangtan Sonyeondan’s (BTS) Official Twitter AZNUR AISYAH Foreign Language and Translation Unit Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Malay Language Department Tokyo University of Foreign Language Studies (Visiting Lecturer) [email protected] ABSTRACT K-pop fans face language barriers on a daily basis when searching for their favourite K-Pop group related news. The translators’ role in mediating information between the international fans with the K-Pop artists is central in delivering the necessary information to its fans around the globe. This study has been motivated by the scarcity of research on the progress of translation in social media microblogging such as Twitter. It was aimed at analysing translation progress occurring in social media, namely the Twitter account, where communication discourse activities actively occurred. Big Hit Entertainment’s Twitter account (@BigHitEnt) was selected as the primary data sample because of the outstanding reputation of Bangtan Sonyeondan (BTS), a K-Pop idol group under the company’s label, in terms of social media engagement. This research employed the Social Media Translational Action (SoMTA) analytical framework, a new research methodology adapted from the Translational Action framework, for its data analysis. The content of the news feed in Twitter’s timeline is mostly written in the Korean language which might not be understood by the international fans who do not speak Korean. -

International Bestsellers

INTERNATIONAL BESTSELLERS Holland Argentina TOP TEN 45s TOP TEN 45s 1 Quiero Tu Vida - Luciana - EMI 1 Cokane In My Brain Dillinger Ariola - - 2 A Marcela - Dragoncito Chippy - Philips 2 Yes Sir, I Can Boogie Baccara CNR - - 3 Ojos Sin Luz - Pomada - RCA 3 Be My Boogie Woogie Baby Mr. Walkie Talkie Phonogram - - 4 Con El Viento A Tu Favor - Camilo Sesto - RCA 4 Sevilla BZN Negram - - 5 Y Te Amare - Ana & Johnny - CBS 5 So You Win Again Hot Chocolate Bovema - - 6 Que Se Va El Cartero - El Cartero/M. Terere - Surco/RCA 6 A Real Mother For Ya Johnny Guitar Watson CBS - - 7 Donde Estan Tus Ojos Negros - Santabarbara - EMI 7 Hey, St. Peter Flash & The Pan Phonogram - - 8 En El Amor Todo Es Empezar - Raffaella Carra - CBS 8 Mamacita Guys & Dolls Negram - - 9 Que Hay Que Hacer Para Olvidar - Danny - RCA 9 Angelo Brotherhood Of Man T. Hiller VIP - - - 10 Otro Ocupa MI Lugar - Miguel Gallardo - EMI 10 Big Bisou - Carlos - Dureco TOP TEN LPs TOP TEN LPs 1 Los Exitos Del Amor - Selection - Microfon 1 Love At The Greek Neil Diamond CBS - - 2 Discoshow - Selection - CBS 2 Summer Melody George Baker Selection Negram - - 3 Musica Cinco - Selection - RCA 3 Hotel California Eagles WEA - - 4 Trilogia De Amor - Donna Summer - Microfon 4 A Real Mother For Ya Johnny Guitar Watson CBS - - 5 Cumbilandia Vol. 2 Los Wawanco - EMI M - 5 Love For Sale - Boney - Dureco 6 Recuerdo El Ayer Donna Summer Microfon Phonogram - - 6 Aan Het Strand - Havenzangers - 7 En Vivo Johnny Rivers EMI WEA - - 7 Rumours - Fleetwood Mac - 8 Musica Poderosa Vol. -

The Guardian, February 12, 1980

Wright State University CORE Scholar The Guardian Student Newspaper Student Activities 2-12-1980 The Guardian, February 12, 1980 Wright State University Student Body Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/guardian Part of the Mass Communication Commons Repository Citation Wright State University Student Body (1980). The Guardian, February 12, 1980. : Wright State University. This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Activities at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Guardian Student Newspaper by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OSU co-eds ponder draft registration, war By JANET WALSH million American men and be involved right up to combat. "YEAH, that would separate So 1 guess, if it's going to be all COLUMBUS. Ohio UPI A women aged 19 and 20. "I'll tell you one thing though, the women from the girls," over, why not be there fighting," Robert Redford poster grinned "It seems like all of a sudden they'd better pass the ERA. Put cracked Sabrina DiMichhele. 18. Ruth said. "Oh, I'm getting from the wall of the cluttered those of us having the easy life Schaffly. what's her first name, Worthington. sitting cross-legged depressed." "Ohio State University dorm room here in college are facing some- yeah Phyllis, put her in the ditch. on the floor. "I'm afraid the world will just and music blared from an ad- thing really serious," Ruth Nier- Make sure she's in the front "You know, I had to do a big sit by and not help us," said jacent hallway, but the women in ir.eyer. -

1941 Brown and Gold Vol 23 No 06 January 17, 1941

Regis University ePublications at Regis University Brown and Gold Archives and Special Collections 1-17-1941 1941 Brown and Gold Vol 23 No 06 January 17, 1941 Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.regis.edu/brownandgold Part of the Catholic Studies Commons Recommended Citation "1941 Brown and Gold Vol 23 No 06 January 17, 1941" (1941). Brown and Gold. 184. https://epublications.regis.edu/brownandgold/184 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives and Special Collections at ePublications at Regis University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brown and Gold by an authorized administrator of ePublications at Regis University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I / EXAM BLUES LIGHTENED Father Tainter FOTO CONTEST OFFERS BY FLUNI(ERS FROLIC Named Director 24 DOLLARS IN PRIZES Good Time for All Guaranteed Three Contests Give Students Chance for Fame and Fortune Say Junior Directors Of Retreat Twenty-four dollars in photographic materials will ''It's the biggest thing since repeal,'' beamed Chet Bo The annual retreat will this year be be conducted by Rev. James Taint- awarded as prizes by the Ranger in the next three relli. "It'll be as exciting as Foley at a Fitch conven months in an effort to stimulate student interest in pho- er, S. J., senior advisor at Campion. tion," commented Mike Kennedy. 'The two gentlemen, tography. Three contests, ending on the fifteenth of Chet Borelli and Michael Kennely, are the co-directors of Father Tainter is director of February, March and April, are planned. -

The TRAVELS of MARCO POLO

The TRAVELS of MARCO POLO INTRODUCTION AFTER AN ABSENCE OF twenty-six years, Marco Polo and his father Nicolo and his uncle Maffeo returned from the spectacular court of Kublai Khan to their old home in Venice. Their clothes were coarse and tattered; the bun dles that they carried were bound in Eastern cloths and their bronzed faces bore evi dence of great hardships, long endurance, and suffering. They had almost forgotten their native tongue. Their aspect seemed foreign and their ac Copyright 1926 by Boni & Liveright, Inc. cent and entire manner bore the strange stamp of the Tartar. Copyright renewed 1953 by Manuel Komroff During these twenty-six years Venice, too, had changed and Copyright 1930 by Horace Liveright, Inc. the travellers had difficulty in finding their old residence. But here at last as they entered the courtyard they were All rights reserved back home. Back from the Deserts of Persia, back from Printed in the United States of America Manufacturing by the Maple-Vail Book Manufacturing Group the lofty steeps of Pamir, from mysterious Tibet, from the dazzling court of Kublai Khan, from China, Mongolia, Burma, Siam, Sumatra, Java; back from Ceylon, where For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write Adam has his tomb, and back from India, the land of myth to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY and marvels. But the dogs of Venice barked as the travellers 10110 knocked on the door of their old home. The Polos had long been thought dead, and the distant Hardcover ISBN 0-87140-657-8 relatives who occupied the house refused admittance to the Paperback ISBN 0-393-97968-7 three shabby and suspicious looking gentlemen. -

Meeting Packet

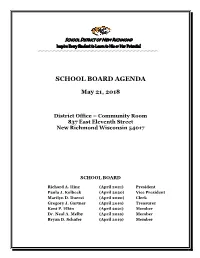

SCHOOL DISTRICT313.0 OF NEW RICHMOND Inspire Every Student to Learn to His or Her Potential SCHOOL BOARD AGENDA May 21, 2018 District Office – Community Room 837 East Eleventh Street New Richmond Wisconsin 54017 SCHOOL BOARD Richard A. Hinz (April 2021) President Paula J. Kolbeck (April 2020) Vice President Marilyn D. Duerst (April 2020) Clerk Gregory J. Gartner (April 2019) Treasurer Kent P. Elkin (April 2021) Member Dr. Neal A. Melby (April 2019) Member Bryan D. Schafer (April 2019) Member Open Forum We welcome you to the meeting of the New Richmond School Board. An open forum is held during each School Board meeting. At this time, citizens residing within the boundaries of the school district may present any policy topic they would like to comment on. Privacy rules do not allow us to discuss any personnel matter or matters concerning individual employees and are not suitable topics for the open forum. The guidelines for the open forum are: 1) The time set aside for the forum is 30 minutes unless extended by the Board. Individual speakers are limited to 5 minutes unless extended by the Board. 2) Please state your name and address and phone number. 3) Open Meeting laws allow us to have limited discussion on topics raised during the Open Forum, though no action can be taken unless the matter has been formally noticed on the agenda. 4) If the speaker requests information or asks a question that cannot be answered at this time, the Board Chair may appoint a member of administration or other board member to respond in writing to the speaker. -

Penner, Wyman R, Auto Body Repair and Repainting

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 114 594 CE 005 456 AUTHOP Manuel, Edward F.; Penner, Wyman R, TITLE Auto Body Repair and Repainting: Instructional Units. INSTITUTION Oklahoma State Dept. of Vocational and Technical Education, Stillwater, Curriculum and Instructional Materials Center. PUB DATE 74 NOTE' 1,241p. EDRS PPICE MF-$2.02 HC-$62.85 Plus Postage DESCPIPTORS *Auto Body Repairmen; Course Content; *Curriculum Guides; Evaluation Criteria; *Instructional Materials; Learning Activities; Post Secondary Education; Secondary Education; Student Evaluation; *Tests; *Trade and Industrial Education; Unit Plan ABSTRPCT The guide contains 11 sections, each consisting of one or more units of instruction designed to provide students with entry-level skills in auto body repair. The sections deal with: introductory and related information; body and frame construction; tools; welding; basic metal repair; hardware, glass, and trim; major metal repair; refinishing; damage estimating; and miscellaneous topics. Each unit includes performance objectives stated as terminal objectives, indicating the subject matter to be covered, and as specific objectives for student performance. All units contain suggested student and teacher activities, information sheets providing the essential content of the unit, tests with answers, and a reference list. Many of the units also have transparency masters, student handout sheets, job sheets designed to teach a skill, and assignment sheets to provide paper and pencil activities. Numerous illustrations are included on the assignment and job sheets, tests, and transparency masters. Progress charts, with predetermined levels of accuracy for evaluating skill attainment, are provided after each major section and contain a listing of all the tasks for which job sheets are included in the units. -

Teaching Materials Collection Is Intended for Use in Conjunction with the ALT Handbook, a JET Programme Publication Produced by CLAIR

TEACHING PROGRAMME MATERIALS COLLECTION JET THE 2013 © 2013, Council of Local Authorities for International Relations (CLAIR) Sogo Hanzomon Building 6F 1-7 Koji-machi, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 102-0083 Tel (03) 5213-1729 Fax (03) 5213-1743 © 2013 (財)自治体国際化協会 〒102-0083 東京都千代田区麹町1-7 相互半蔵門ビル6階 Tel (03) 5213-1728 fax (03) 5213-1743 ・ This publication is for personal, non-commercial use by Japan Exchange and Teaching (JET) Programme participants. ・ この冊子はJET事業参加者の使用に供するものであり、営利目的による使用を厳禁します。 ・ No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any way or by any means electronic, mechanical, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Council of Local Authorities for International Relations (CLAIR). JET participants are free to copy and use for classes as needed. ・ 記載されている情報については(財)自治体国際化協会から事前の文書による許可を得ない限り、 いかなる方法によっても、一切の複製、転写を禁じます。 Introduction Purpose This Teaching Materials Collection is intended for use in conjunction with the ALT Handbook, a JET Programme publication produced by CLAIR. With these publications, CLAIR hopes to provide information for JET participants on teaching in Japan and how to adapt to their workplaces. Resource Sources This Teaching Materials Collection and the complementary ALT Handbook are compilations of information collected from participants of the former British English Teachers Scheme (BETS) and the Monbusho English Fellows (MEF) Programme, as well as past and current JET participants. This Teaching Materials Collection, in conjunction with the ALT Handbook, were previously collectively known as the Resource and Teaching Materials Handbook. These materials were split in two and the Teaching Materials Collection is now provided in an online format. A PDF version of the ALT Handbook is also available on the JET Programme website at: www.jetprogramme.org/e/current/publications.html CLAIR would like to express special thanks to all of the JET participants and JET alumni who submitted new material for the 2013 edition of the Teaching Materials Collection. -

The Tiger (Student Newspaper), April 11, 1899-June 7, 1899

'%- Colorado College Library | Vo-fcC Library No...<o&&.5.5 1 1 From... | H f Receivi d ] "' " i * !• p.i .'': . - \ ISlPi ^ifS* ^v-V mm U?&iS*p#^, B 1 The Tiger. Vol. 1. No. 1. COLORADO SPRINGS, COLO., TUESDAY, APRIL 11, 1899. Price 5 Cents. r it'll t held, anil was so elated at his success that he ""Ti>"ii n-.li> ]ii,c ;,,! tried to steal second, but Packard and t. ninth frus- yeur linri I ronvtml C.C.26== '" "" this side 'I"" »rn, ,„.„.|, • ,. trated laudable attempt, and the was out GLEE CLUB'S far ,,i, .,„„,, ,,n Score: C. C. 8; E. D. H. S„ 0. '>" "'« "'"'I'l ».H. il»' ling II.. Indira I-..I >" EAST DENVER 0. FOURTH INNlNi: SPRING ..I II.. u elton „i I...I ,...„ Clarke reached first on V an V t'a muff of the TOUR. ball McCarthy hnd thrown Packard gave Hutch- BOULDER BOYS WAX RAMPANT. inson a chance to distinguish himself; the little It. eight o'clock II..- Ini-gc Oiiero II...... ..... ncuv ttvehed Clarke out, but in his haste to coiu])lele MOST FIRST GAME OF THE SEASON. the double play, over Fleet's SUCCESSFUL IN THE HISTORY he threw Van head, seals logcllici-, nut] the l...v.. ...... and Packard reached second. Harry's brother fell eery I OF THE CLUB. oicil ..I... il.... ii.i.i reached third on a passed ball. Cooley singled, i Icnrnccl Llicac gmvo .....I ... scoring Packard. It ,,|IM ' 1 Btililenls The gentleman from Lad eiucd In Hi.... .!„.. iimigniu for then stole second, Gearin sent Ins third angle out III.' Ill.-l III...' I,, „ I.I .milk IVS|,.,I |,„ l',, I, „,|,(,, Denver Boys Shut Out in the Third into loft field, and Cooley attempted t home, but was thrown out. -

The Management of Japanese Cultural “Odor” in Pokémon

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Theses and Dissertations 10-25-2018 A Pokébalancing Act: The Management Of Japanese Cultural “odor” In Pokémon Nicholas Raes Illinois State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Raes, Nicholas, "A Pokébalancing Act: The Management Of Japanese Cultural “odor” In Pokémon" (2018). Theses and Dissertations. 1022. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd/1022 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A POKÉBALANCING ACT: THE MANAGEMENT OF JAPANESE CULTURAL “ODOR” IN POKÉMON NICHOLAS RAES 216 Pages In this project, I analyzed two seasons of the Pokémon anime to discover patterns of cultural “odor” management employed by the show’s producers and editors. In the first season of Pokémon , the producers of the anime included many symbolic representations of Japanese cultural artifacts within the visual features of the show. However, between the Japanese and US versions of the season, most instances of Japanese linguistic text were either “scrubbed” from scenes entirely or replaced with English text. These techniques struck a careful balance between including and excluding Japanese specificity within the first season, subtly expressing to non- Japanese audiences the Japanese origin of the show. However, in the twentieth season, producers removed symbolic representations of Japanese culture almost entirely – replacing these instead with symbols indicative of Hawaiian culture.