BTS) Official Twitter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preparing for the Possibility of a North Korean Collapse

CHILDREN AND FAMILIES The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit institution that EDUCATION AND THE ARTS helps improve policy and decisionmaking through ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT research and analysis. HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE This electronic document was made available from INFRASTRUCTURE AND www.rand.org as a public service of the RAND TRANSPORTATION Corporation. INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS LAW AND BUSINESS NATIONAL SECURITY Skip all front matter: Jump to Page 16 POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Support RAND Purchase this document TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY Browse Reports & Bookstore Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND National Security Research Division View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND electronic documents to a non-RAND website is prohibited. RAND electronic documents are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This report is part of the RAND Corporation research report series. RAND reports present research findings and objective analysis that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND reports undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for re- search quality and objectivity. Preparing for the Possibility of a North Korean Collapse Bruce W. Bennett C O R P O R A T I O N NATIONAL SECURITY RESEARCH DIVISION Preparing for the Possibility of a North Korean Collapse Bruce W. -

Yun Mi Hwang Phd Thesis

SOUTH KOREAN HISTORICAL DRAMA: GENDER, NATION AND THE HERITAGE INDUSTRY Yun Mi Hwang A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2011 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/1924 This item is protected by original copyright This item is licensed under a Creative Commons Licence SOUTH KOREAN HISTORICAL DRAMA: GENDER, NATION AND THE HERITAGE INDUSTRY YUN MI HWANG Thesis Submitted to the University of St Andrews for the Degree of PhD in Film Studies 2011 DECLARATIONS I, Yun Mi Hwang, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 80,000 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student and as a candidate for the degree of PhD in September 2006; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2006 and 2010. I, Yun Mi Hwang, received assistance in the writing of this thesis in respect of language and grammar, which was provided by R.A.M Wright. Date …17 May 2011.… signature of candidate ……………… I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of PhD in the University of St Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. -

Issue 9 •Sports Lingo P

TheStudent photos by DeCloud Studios Miegian Volume 57 Issue 9 •Sports Lingo p. 15• Senior Edition •Departing Teachers p. 2• Seniors missing from mural (due to unavailability): May 2014 •One Acts p. 4•Senior pullout• Daniel Becker, Ryan Estrada, McKinley Johnson, Lucy Kraus Miegian N E W S Small but Mighty Five Stags Are Leaving the Herd News Car Raffle Tickets The total sold by the students was $21,085 for 60% of the $35,000 goal. The seniors brought in 35% of their goal, juniors 50% of their goal, sophomores 61% of their goal and freshmen 80% of theirs. The top sellers were Rachel Lavery with $300 and Tyler Pennell with Mike Bohaty- 26 years Paula Munro- 20 years Amy Lukert- 7 years Emily McGinnis- 3 years Fred Turner- 2 years $275. The winner of the car was the What did you teach or what was your role? Also, with what type of fondest memories come from the more relaxed student interactions in rehearsals, activities were you involved? lessons, at basketball games, or on a bus for a field trip.” Kincaid family, who donated it back to • Mike Bohaty- “My first two years I was associate principal and was in charge of • Fred Turner- “Beating St. Thomas Aquinas like a drum for the championship of the the school before it was purchased by the St. Thomas Aquinas Tournament, The relationships developed between my players discipline, attendance and athletics. The third year a ‘Director for Attendance’ was Belfield family. hired. I was in charge of half the discipline and attendance and had activities. -

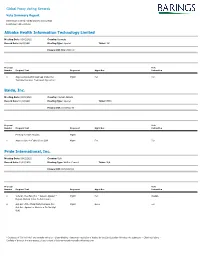

Global Proxy Voting Records

Global Proxy Voting Records Vote Summary Report Date range covered: 03/01/2021 to 03/31/2021 Location(s): All Locations Alibaba Health Information Technology Limited Meeting Date: 03/01/2021 Country: Bermuda Record Date: 02/23/2021 Meeting Type: Special Ticker: 241 Primary ISIN: BMG0171K1018 Proposal Vote Number Proposal Text Proponent Mgmt Rec Instruction 1 Approve Revised Annual Cap Under the Mgmt For For Technical Services Framework Agreement Baidu, Inc. Meeting Date: 03/01/2021 Country: Cayman Islands Record Date: 01/28/2021 Meeting Type: Special Ticker: BIDU Primary ISIN: US0567521085 Proposal Vote Number Proposal Text Proponent Mgmt Rec Instruction Meeting for ADR Holders Mgmt 1 Approve One-to-Eighty Stock Split Mgmt For For Pride International, Inc. Meeting Date: 03/01/2021 Country: USA Record Date: 12/01/2020 Meeting Type: Written Consent Ticker: N/A Primary ISIN: US74153QAJ13 Proposal Vote Number Proposal Text Proponent Mgmt Rec Instruction 1 Vote On The Plan (For = Accept, Against = Mgmt For Abstain Reject; Abstain Votes Do Not Count) 2 Opt Out of the Third-Party Releases (For = Mgmt None For Opt Out, Against or Abstain = Do Not Opt Out) * Instances of "Do Not Vote" are normally owing to: - Share-blocking - temporary restriction of trading by the Sub-Custodian following vote submission - Client restrictions - Conflicts of Interest. For any queries, please contact [email protected] Global Proxy Voting Records Vote Summary Report Date range covered: 03/01/2021 to 03/31/2021 Location(s): All Locations The -

An Interview with Amor Towles

THE 1511 South 1500 East Salt Lake City, UT 84105 InkslingerSpring Issue 2 019 801-484-9100 The Arc of History: A Gentleman in Moscow, Amor Towles An Interview with Amor Towles— A young Russian count is saved from He’ll be in SLC April 2! a Bolshevik bullet because of a pre- by Betsy Burton revolution pro-revolution poem. Given his aristocratic upbringing he can’t go I called Amor Towles to talk to him free. So what is a Communist Commit- about A Gentleman in Moscow, but be- tee of the Commissariat to do? Put this fore we started with questions he won- unsuspicious suspect under house arrest dered who I was and whether we hadn’t in the grand hotel in which he’s staying, of met before at some book dinner or course. A hotel that, like Count Alexan- other. Knowing how often he speaks in der Ilyich Rostov himself, is allowed to exist for secret reasons public, I was surprised he remembered. of state. Our Count is nothing if not creative, and it isn’t long We had met, I said. Had sat next to one before his courtly manners and charm create a constella- another at a breakfast—an American tion of comrades that will inhabit your heart: Nina, a child Booksellers event at which he was the who teaches him the fine art of spying; her daughter Sophia, keynote speaker a couple of years ago. I decades later; his old friend, the poet Mishka; the glamorous thought so, he said. After chatting for a actress, Anna Urbanova; the hotel staff… As witty, cosmopoli- few minutes, I asked my first question tan, and unflappable as the Scarlet Pimpernel on the outside, Amor Towles, who will be in SLC as kind and as thoughtful as Tolstoy’s Pierre Bezukhov on the which was, admittedly, longwinded. -

The Korean Wave As a Localizing Process: Nation As a Global Actor in Cultural Production

THE KOREAN WAVE AS A LOCALIZING PROCESS: NATION AS A GLOBAL ACTOR IN CULTURAL PRODUCTION A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Ju Oak Kim May 2016 Examining Committee Members: Fabienne Darling-Wolf, Advisory Chair, Department of Journalism Nancy Morris, Professor, Department of Media Studies and Production Patrick Murphy, Associate Professor, Department of Media Studies and Production Dal Yong Jin, Associate Professor, School of Communication, Simon Fraser University © Copyright 2016 by Ju Oak Kim All Rights Reserved ii ABSTRACT This dissertation research examines the Korean Wave phenomenon as a social practice of globalization, in which state actors have promoted the transnational expansion of Korean popular culture through creating trans-local hybridization in popular content and intra-regional connections in the production system. This research focused on how three agencies – the government, public broadcasting, and the culture industry – have negotiated their relationships in the process of globalization, and how the power dynamics of these three production sectors have been influenced by Korean society’s politics, economy, geography, and culture. The importance of the national media system was identified in the (re)production of the Korean Wave phenomenon by examining how public broadcasting-centered media ecology has control over the development of the popular music culture within Korean society. The Korean Broadcasting System (KBS)’s weekly show, Music Bank, was the subject of analysis regarding changes in the culture of media production in the phase of globalization. In-depth interviews with media professionals and consumers who became involved in the show production were conducted in order to grasp the patterns that Korean television has generated in the global expansion of local cultural practices. -

Run Bts Bingo

www.cactuspop.com RUN BTS BINGO The same RM breaks They play rock Jimin falls over scene is Hand holding something paper scissors laughing replayed 3 times Squeaky sound Someone sings V shows his Jin blows a They eat effect a BTS song artistic side kiss something Jin does Someone gets Jungkook J-Hope dances windscreen BTS roasted by the shows his Free Space wiper laugh other members strength Suga falls Jin gets angry BTS are nice to Someone Jin cracks a asleep and yells staff speaks satoori dad joke Someone Big Hit censors The subs seem Someone yells Worldwide mentions someone’s like fake subs “woooaaahhh” handsome ARMY body RUN BTS BINGO Someone yells Squeaky sound The subs seem BTS are nice to Hand holding “woooaaahhh” effect like fake subs staff Jin does The staff Suga falls ㅋㅋㅋㅋㅋㅋㅋ windscreen change the J-Hope dances asleep wiper laugh ㅋㅋ rules Worldwide V shows his BTS Someone sings RM breaks handsome artistic side Free Space a BTS song something The same Jin gets angry They eat They play rock scene is Jin blows a and yells something paper scissors replayed 3 kiss times Big Hit censors Jungkook Someone Jimin falls over Jin cracks a someone’s shows his speaks satoori laughing dad joke body strength RUN BTS BINGO Jin blows a Someone sings Jin gets angry Someone yells Hand holding kiss a BTS song and yells “woooaaahhh” They play rock They eat Squeaky sound V shows his Jin cracks a paper scissors something effect artistic side dad joke The same Someone Someone gets The subs seem scene is mentions BTS roasted by the like fake subs Free -

Conceptually Androgynous

Umeå Center for Gender Studies Conceptually androgynous The production and commodification of gender in Korean pop music Petter Almqvist-Ingersoll Master Thesis in Gender Studies Spring 2019 Thesis supervisor: Johanna Overud, Ph. D. ABSTRACT Stemming from a recent surge in articles related to Korean masculinities, and based in a feminist and queer Marxist theoretical framework, this paper asks how gender, with a specific focus on what is referred to as soft masculinity, is constructed through K-pop performances, as well as what power structures are in play. By reading studies on pan-Asian masculinities and gender performativity - taking into account such factors as talnori and kkonminam, and investigating conceptual terms flower boy, aegyo, and girl crush - it forms a baseline for a qualitative research project. By conducting qualitative interviews with Swedish K-pop fans and performing semiotic analysis of K-pop music videos, the thesis finds that although K-pop masculinities are perceived as feminine to a foreign audience, they are still heavily rooted in a heteronormative framework. Furthermore, in investigating the production of gender performativity in K-pop, it finds that neoliberal commercialism holds an assertive grip over these productions and are thus able to dictate ‘conceptualizations’ of gender and project identities that are specifically tailored to attract certain audiences. Lastly, the study shows that these practices are sold under an umbrella of ‘loyalty’ in which fans are incentivized to consume in order to show support for their idols – in which the concept of desire plays a significant role. Keywords: Gender, masculinity, commercialism, queer, Marxism Contents Acknowledgments ................................................................................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................. -

BTS, Digital Media, and Fan Culture

19 Hyunshik Ju Sungkyul University, South Korea Premediating a Narrative of Growth: BTS, Digital Media, and Fan Culture This article explores the landscape of fan engagements with BTS, the South Korean idol group. It offers a new approach to studying digital participation in fan culture. Digital fan‐based activity is singled out as BTS’s peculiarity in K‐pop’s history. Grusin’s discussion of ‘premediation’ is used to describe an autopoietic system for the construction of futuristic reality through online communication between BTS and ARMY, as the fans are called. As such, the BTS’s live performance is experienced through ARMY’s premediation, imaging new identities of ARMY as well as BTS. The way that fans engage digitally with BTS’s live performance is motivated by a narrative of growth of BTS with and for ARMY. As an agent of BTS’s success, ARMY is crucial in driving new economic trajectories for performative products and their audiences, radically intervening in the shape and scope of BTS’s contribution to a global market economy. Hunshik Ju graduated with Doctor of Korean Literature from Sogang University in South Korea. He is currently a full‐time lecturer at the department of Korean Literature and Language, Sungkyul University. Keywords: BTS, digital media fan culture, liveness, premediation Introduction South Korean (hereafter Korean) idol group called Bulletproof Boy AScouts (hereafter BTS) delivered a speech at the launch of “Generation Unlimited,” United Nations Children’s Fund’s (UNICEF) new youth agenda, at the United Nations General Assembly in New York on September 24, 2018. In his speech, BTS’s leader Kim Nam Jun (also known as “RM”) stressed the importance of self-love by stating that one must love oneself wholeheartedly regardless of the opinions and judgments of others.1 Such a message was not new to BTS fans, since the group’s songs usually raise concerns and reflections about young people’s personal growth. -

2020 Korean Books for Young Readers

2020 Korean Books for Young Readers Korean Board on Books for Young People (IBBY Korea) About Contents KBBY and this Catalog KBBY(Korean Board on Books for Young People) was founded in 1995 7 Korean Nominees for the Hans Christian Andersen Awards 4 as the Korea national section of the International Board on Books for Young People (IBBY). Korean Nominations for the IBBY Honour List 2020 12 To fulfill IBBY’s mission, KBBY works as a network of professionals from both home and abroad, collecting and sharing information on Korean Nominations for BIB 2019 14 children’s and juvenile literature. KBBY also works in close partnership with the other national sections of IBBY to contribute to promoting Korean Nominations for Silent Books 2019 22 cross-cultural exchange in children’s literature. Recent Picture Books Recommended by KBBY Since 2017 25 KBBY organizes international book exhibitions in collaboration with library networks, in efforts to share with the Korean audience the in- formation on global books generated through the awards and activ- Recent Chapter Books and Novels Recommended by KBBY Since 2017 37 ities of IBBY. Moreover, KBBY is committed to providing information on outstanding Korean children’s and juvenile literature with readers Recent Non-fiction Recommended by KBBY Since 2017 50 across the world. This catalog presents the Korean nominees of the Hans Christian An- dersen Awards, who have made a lasting impact on children’s litera- ture not only at home but also to the world at large. Also included is a collection of the Korean children’s books recommended by the book selection committee of KBBY: Korean nominations for the IBBY Honour List, BIB, Silent Books; recent picutre books, chapter books & novels, and non-finction books. -

A Study and Performance Analysis of Selected Art Songs by Un-Yeong Na" (2010)

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2010 A Study and Performance Analysis of Selected Art Songs by Un- Yeong Na Min Sue Kim West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Kim, Min Sue, "A Study and Performance Analysis of Selected Art Songs by Un-Yeong Na" (2010). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 2991. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/2991 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Study and Performance Analysis of Selected Art Songs by Un-Yeong Na Min Sue Kim Research Project submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Performance: Voice Dr. Kathleen Shannon, Chair and Research Advisor Professor Robert Thieme Dr. Chris Wilkinson Dr. Peter Amstutz Dr. Georgia Narsavage Division of Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2010 Keywords: Un-Yeong Na, Korean Art Song, Korean Traditional Music Copyright 2010 Min Sue Kim ABSTRACT A Study and Performance Analysis of Selected Art Songs of Un-Yeong Na Min Sue Kim Korea‘s history spans over 5,000 years. -

K-Pop: South Korea and International Relations S1840797

Eliana Maria Pia Satriano [email protected] s1840797 Word count: 12534 Title: K-pop: South Korea and International Relations s1840797 Table of Contents: 1. Chapter 1 K-pop and International Relations………………………………..……..…..3-12 1.1 Introduction ……………………………………………………………………..…..3-5 1.2 K-pop: from the National to the International Market: The History of K-pop………5-6 1.3 The Drivers Behind the K-pop Industry..………………………………….….….…6-10 1.4 The Involvement of the South Korean Government with Cultural Industries.…… 10-12 2. Chapter 2 Soft Power and Diplomacy, Music and Politics ……………………………13-17 2.1 The Interaction of Culture and Politics: Soft Power and Diplomacy………………13-15 2.2 Music and Politics - K-pop and Politics……………………………………………15-17 3. Chapter 3 Methodology and the Case Study of BTS……………………………..……18-22 3.1 Methodology………………………………………………………………….……18-19 3.2 K-Pop and BTS……………………………………………………………….……19-20 3.3 Who is BTS?………………………………………………………………….……20-22 3.4 BTS - Beyond Korea……………………………………………………………….…22 4. Chapter 4 Analysis ……………………………………………………….…….…….. 23-38 4.1 One Dream One Korea and Inter-Korea Summit……….…………………..……..23-27 4.2 BTS - Love Myself and Generation Unlimited Campaign…………………….…..27-32 4.3 Korea -France Friendship Concert..………………………………………..….…..33-35 4.4 Award of Cultural Merit…………………………………………….………….…..35-37 4.5 Discussion and Conclusion…………………………………………………….…..37-38 Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………….….39-47 !2 s1840797 CHAPTER 1: K-pop and International Relations (Seventeen 2017) 1.1 Introduction: South Korea, despite its problematic past, has undergone a fast development in the past decades and is now regarded as one of the most developed nations. A large part of its development comes from the growth of Korean popular culture, mostly known as Hallyu (Korean Wave).