The Spitzer View of the Extragalactic Universe*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Publications for Dr. Peter L. Capak 1 of 21 Publication Summary 369

Publications for Dr. Peter L. Capak Publication Summary 369 Publications 319 Refereed Publications Accepted or Submitted 50 Un-refereed Publications Top 1% of Cited Researchers in 2017-2019 >30,000 Citations >1,600 Citations on first author papers 99 papers with >100 citations, 6 as first author. H Index = 99 First Author publications 1) Capak et al., 2015, “Galaxies at redshifts 5 to 6 with systematically low dust content and high [C II] emission”, Nature, 522, 455 2) Capak et al., 2013, “Keck-I MOSFIRE Spectroscopy of the z ~ 12 Candidate Galaxy UDFj-39546284”, ApJL, 733, 14 3) Capak et al., 2011, “A massive protocluster of galaxies at a redshift of z~5.3” , Nature, 470, 233 4) Capak et al., 2010, “Spectroscopy and Imaging of three bright z>7 candidates in the COSMOS survey”, ApJ, 730, 68 5) Capak et al., 2008, "Spectroscopic Confirmation Of An Extreme Starburst At Redshift 4.547", ApJL, 681, 53 6) Capak et. al., 2007, "The effects of environment on morphological evolution between 0<z<1.2 in the COSMOS Survey", ApJS, 172, 284 7) Capak et. al., 2007, "The First Release COSMOS Optical and Near-IR Data and Catalog", ApJS, 172, 99 8) Capak, 2004, “Probing global star and galaxy formation using deep multi-wavelength surveys”, Ph.D. Thesis 9) Capak et. al., 2004, "A Deep Wide-Field, Optical, and Near-Infrared Catalog of a Large Area around the Hubble Deep Field North", AJ, 127, 180 Other Publications (P. Capak was a leading author in bolded entries) 10) Faisst et al., 2020, “The ALPINE-ALMA [CII] survey: Multi-Wavelength Ancillary Data. -

Highlights and Discoveries from the Chandra X-Ray Observatory1

Highlights and Discoveries from the Chandra X-ray Observatory1 H Tananbaum1, M C Weisskopf2, W Tucker1, B Wilkes1 and P Edmonds1 1Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, 60 Garden Street, Cambridge, MA 02138. 2 NASA/Marshall Space Flight Center, ZP12, 320 Sparkman Drive, Huntsville, AL 35805. Abstract. Within 40 years of the detection of the first extrasolar X-ray source in 1962, NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory has achieved an increase in sensitivity of 10 orders of magnitude, comparable to the gain in going from naked-eye observations to the most powerful optical telescopes over the past 400 years. Chandra is unique in its capabilities for producing sub-arcsecond X-ray images with 100-200 eV energy resolution for energies in the range 0.08<E<10 keV, locating X-ray sources to high precision, detecting extremely faint sources, and obtaining high resolution spectra of selected cosmic phenomena. The extended Chandra mission provides a long observing baseline with stable and well-calibrated instruments, enabling temporal studies over time-scales from milliseconds to years. In this report we present a selection of highlights that illustrate how observations using Chandra, sometimes alone, but often in conjunction with other telescopes, have deepened, and in some instances revolutionized, our understanding of topics as diverse as protoplanetary nebulae; massive stars; supernova explosions; pulsar wind nebulae; the superfluid interior of neutron stars; accretion flows around black holes; the growth of supermassive black holes and their role in the regulation of star formation and growth of galaxies; impacts of collisions, mergers, and feedback on growth and evolution of groups and clusters of galaxies; and properties of dark matter and dark energy. -

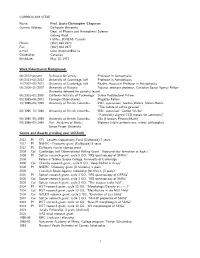

Prof. Scott Christopher Chapman Current Address: Dalhousie University Dept

CURRICULUM VITAE Name: Prof. Scott Christopher Chapman Current Address: Dalhousie University Dept. of Physics and Atmospheric Science Coburg Road Halifax, B3H1A6, Canada Phone: (902) 494 2370 Fax: (902) 494 2377 e-mail: [email protected] Citizenship: Canadian Birthdate: May 13, 1971 Work/Educational Background 08/2012{present Dalhousie University Professor in Astrophysics 06/2011{08/2012 University of Cambridge, IoA Professor in Astrophysics 10/2007{05/2011 University of Cambridge, IoA Reader, Associate Professor in Astrophysics 06/2006{10/2007 University of Victoria Adjunct assistant professor, Canadian Space Agency Fellow (6 months deferred for parental leave) 06/2001{01/2006 California Institute of Technology Senior Postdoctoral Fellow 05/1999{06/2001 Carnegie Observatories Magellan Fellow 10/1996{09/1999 University of British Columbia PhD, supervisors: Gordon Walker, Simon Morris \The nature of active galaxies" 09/1995{10/1996 University of British Columbia MSc, supervisor: Gordon Walker \A precisely aligned CCD mosaic for astronomy" 09/1990{05/1995 University of British Columbia BSc (Honours Physics/Math) 09/1988{05/1990 Van. Academy of Music/ Diploma (violin performance, minor: philosophy) Simon Fraser University Grants and Awards (totaling over US$3mil) 2012 PI CFI - Leaders Opportunity Fund (Dalhousie) 5 years 2012 PI NSERC - Discovery grant (Dalhousie) 5 years 2012 PI Dalhousie faculty startup grant 2009 CoI Cambridge, IoA Observational Rolling Grant \Obscured star formation at high-z" 2008 PI Spitzer research grant, cycle -

FY13 High-Level Deliverables

National Optical Astronomy Observatory Fiscal Year Annual Report for FY 2013 (1 October 2012 – 30 September 2013) Submitted to the National Science Foundation Pursuant to Cooperative Support Agreement No. AST-0950945 13 December 2013 Revised 18 September 2014 Contents NOAO MISSION PROFILE .................................................................................................... 1 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................ 2 2 NOAO ACCOMPLISHMENTS ....................................................................................... 4 2.1 Achievements ..................................................................................................... 4 2.2 Status of Vision and Goals ................................................................................. 5 2.2.1 Status of FY13 High-Level Deliverables ............................................ 5 2.2.2 FY13 Planned vs. Actual Spending and Revenues .............................. 8 2.3 Challenges and Their Impacts ............................................................................ 9 3 SCIENTIFIC ACTIVITIES AND FINDINGS .............................................................. 11 3.1 Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory ....................................................... 11 3.2 Kitt Peak National Observatory ....................................................................... 14 3.3 Gemini Observatory ........................................................................................ -

Enhancing LSST Science with Euclid Synergy Arxiv:1904.10439V1 [Astro

Enhancing LSST Science with Euclid Synergy P. Capak, J-C. Cuillandre, F. Bernardeau, F. Castander, R. Bowler, C. Chang, C. Grillmair, P. Gris, T. Eifler, C. Hirata, I. Hook, B. Jain, K. Kuijken, M. Lochner, P. Oesch, S. Paltani, J. Rhodes, B. Robertson, D. Rubin, R. Scaramella, C. Scarlata, D. Scolnic, J. Silverman, S. Wachter, Y. Wang, The Tri-Agency Working Group November, 30, 2018 Abstract This white paper is the result of the Tri-Agency Working Group (TAG) appointed to develop synergies between missions and is intended to clarify what LSST observations are needed in order to maximally enhance the combined science output of LSST and Euclid. To facilitate LSST planning we provide a range of possible LSST surveys with clear metrics based on the improvement in the Dark Energy figure of merit (FOM). To provide a quantifiable metric we present five survey options using only between 0.3 and 3.8% of the LSST 10 year survey. We also provide information so that the LSST DDF cadence can possibly be matched to those of Euclid in common deep fields, SXDS, COSMOS, CDFS, and a proposed new LSST deep field (near the Akari Deep Field South). Co-coordination of observations from the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST) and Euclid will lead to a significant number of synergies. The combination of optical multi-band imaging from LSST with high resolution optical and near-infrared photom- etry and spectroscopy from Euclid will not only improve constraints on Dark Energy, but provide a wealth of science on the Milky Way, local group, local large scale struc- ture, and even on first galaxies during the epoch of reionization. -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 16 March 2017 Version of attached le: Published Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Lansbury, G. B. and Stern, D. and Aird, J. and Alexander, D. M. and Fuentes, C. and Harrison, F. A. and Treister, E. and Bauer, F. E. and Tomsick, J. A. and Balokovic, M. and Del Moro, A. and Gandhi, P. and Ajello, M. and Annuar, A. and Ballantyne, D. R. and Boggs, S. E. and Brandt, N. and Brightman, M. and Chen, C. J. and Christensen, F. E. and Civano, F. and Comastri, A. and Craig, W. W. and Forster, K. and Grefenstette, B. W. and Hailey, C. J. and Hickox, R. and Jiang, B. and Jun, H. and Koss, M. and Marchesi, S. and Melo, A. D. and Mullaney, J. R. and Noirot, G. and Schulze, S. and Walton, D. J. and Zappacosta, L. and Zhang, W. (2017) 'The NuSTAR serendipitous survey : the 40-month catalog and the properties of the distant high-energy X-ray source population.', Astrophysical journal., 836 (1). p. 99. Further information on publisher's website: https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/836/1/99 Publisher's copyright statement: c 2017. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. -

The James Webb Space Telescope the First Light Machine Dr

the James Webb SPACE TELESCOPE THE FIRST LIGHT MACHINE Dr. H. Philip Stahl is the James Webb Space Presentation by Telescope Optical Telescope Element Mirror Optics Lead, Dr. H. Philip Stahl responsible for its primary, secondary and tertiary mirrors. Tuesday, March 12th He is a Senior Optical 8:00 pm Physicist at NASA Marshall Space Flight Center. 1200 EECS Bldg, U of M, North Campus Scheduled to begin its 10 year mission after 2018, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) will search for the first luminous objects of the Universe to help answer fun- damental questions about how the Universe came to look like it does today. At 6.5 meters in diameter, JWST will be the world’s largest space telescope. This talk reviews science objectives for JWST and how they drive the JWST architecture, e.g. aperture, wavelength range and operating temperature. Additionally, the talk provides an over- view of the JWST primary mirror technology development and fabrication status. 2/13/2013 James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) JWST Summary • Mission Objective – Study origin & evolution of galaxies, stars & planetary systems – Optimized for near infrared wavelength (0.6 –28 µm) – 5 year Mission Life (10 year Goal) • Organization – Mission Lead: Goddard Space Flight Center – International collaboration with ESA & CSA – Prime Contractor: Northrop Grumman Space Technology – Instruments: – Near Infrared Camera (NIRCam) – Univ. of Arizona – Near Infrared Spectrometer (NIRSpec) – ESA – Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) – JPL/ESA – Fine Guidance Sensor (FGS) – CSA – Operations: -

1 I Articles Dans Des Revues Avec Comité De Lecture

1 I Articles dans des revues avec comité de lecture (ACL) internationales II Articles dans des revues sans comité de lecture (SCL) NB : La liste des publications est donnée de façon exhautive par équipe, ce qui signifie qu’il existe des redondances chaque fois qu’une publication est cosignée pas des membres dépendant d’équipes différentes. Par contre, certains chercheurs sont à cheval sur deux équipes, dans ce cas il leur a été demandé de rattacher leurs publications seulement à l’une ou à l’autre équipe en fonction de la nature de la publication et la raison de leur rattachement à deux équipes. I Articles dans des revues avec comité de lecture (ACL) internationales ANNÉE 2006 A / Equipe « Physique des galaxies » 1. Aguilar, J.A. et al. (the ANTARES collaboration, 214 auteurs). First results of the Instrumentation Line for the deep- sea ANTARES neturino telescope Astroparticle Physic 26, 314 2. Auld, R.; Minchin, R. F.; Davies, J. I.; Catinella, B.; van Driel, W.; Henning, P. A.; Linder, S.; Momjian, E.; Muller, E.; O'Neil, K.; Boselli, A.; et 18 coauteurs. The Arecibo Galaxy Environment Survey: precursor observations of the NGC 628 group, 2006, MNRAS,.371,1617A 3. Boselli, A.; Boissier, S.; Cortese, L.; Gil de Paz, A.; Seibert, M.; Madore, B. F.; Buat, V.; Martin, D. C. The Fate of Spiral Galaxies in Clusters: The Star Formation History of the Anemic Virgo Cluster Galaxy NGC 4569, 2006, ApJ, 651, 811B 4. Boselli, A.; Gavazzi, G. Environmental Effects on Late-Type Galaxies in Nearby Clusters -2006, PASP, 118, 517 5. -

Science Briefing 8/8/2019

Science Briefing 8/8/2019 Dr. Garth Illingworth (UC Santa Cruz) Deep Fields: Chandra and Hubble Uncover the Dr. Belinda Wilkes (CXC Director, CfA | Growth of Early Galaxies Harvard & SAO) Dr. Rutuparna Das (CfA | Harvard & SAO) Facilitator: Dr. Chris Britt Outline of this Science Briefing 1. Dr. Garth Illingworth (UC Santa Cruz) Exploring the Realm of the First Galaxies with Hubble and JWST 2. Dr. Belinda Wilkes (CXC Director, CfA | Harvard & SAO) NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory: Celebrating 20 years 3. Q&A 4. Dr. Rutuparna Das (CfA | Harvard & SAO) Resources on Deep Fields, galaxy growth, and Chandra’s 20th anniversary 5. Q & A 2 XDF eXtreme Deep Field NASA’s Universe of Learning Science Briefing Exploring the Realm of the First Galaxies with Hubble and JWST Garth Illingworth University of California Santa Cruz firstgalaxies.org 3 gdi Hubble Wide Field Camera 3 (infrared light) 2009 4 gdi 2009 our last (close) view of Hubble 5 gdi Chandra Hubble NASA’s Great Observatories Spitzer 6 gdi telescopes are “time machines” looking back through time XDF: deepest ever Hubble image – in 2012 from 10 years of Hubble data 7 gdi this image is a “history book” the story of how galaxies formed and grew through nearly all of time from a few hundred million years after the Big Bang through 13 billion years 8 gdi Hubble Legacy Field 2019 each of the three Great Observatories – Chandra, Hubble and Spitzer – have contributed about 6-7 million seconds (about 75-80 days) of exposure on this field over the last 15-20 years NASA, ESA, GDI, Magee + HLF Team -

Existing Large Observing Programs

Major Programs using the Great Observatories The following tables collect major science programs undertaken by the three Great Observatories. Most of these programs are drawn from the following proposal subsets: HST Large Programs: >100 orbits or > 100 snapshot targets; HST Treasury Programs: major science programs that include distributing data products to the science community; see http://archive.stsci.edu/hst/tall.html Chandra Large Programs: > 300 ksecs Chandra Very Large Programs: > 1 Megasecs see http://asc.harvard.edu/target_lists/index.html Spitzer Legacy Programs: see http://ssc.spitzer.caltech.edu/legacy/ The individual programs have been grouped under broad subject headings, and similar programs are as far as possible, listed together. Solar System & Extrasolar Planets Program PI Title Comments HST 8267 Gilliland Taking the Measure of Planets in Deep ACS imaging the Globular Cluster 47 Tuc at multiple epochs HST 8583 Storrs Imaging snapshots of asteroids WFPC2 HST 8699 Lamy The origin of short-period comets WFPC2 CXC6 Lisse Comet 9P/Tempel 1 during the ACIS-S Deep Impact encounter HST 9060, Noll Imaging of Kuiper belt asteroids ACS & NICMOS 9386, 10801 HST 9433 Bernstein The size distribution of KBOs ACS HST 10862 Clarke Comprehensive Auroral Imaging of ACS/SBC Jupiter and Saturn during the International Heliophysical Year Stellar Programs Program PI Title Comments HST 6119 Bond Snapshot survey for companions to WFPC2 Planetary-Nebula nuclei CXC6 Kastner The X-ray spectrum of a planetary ACIS-S/LETG nebula at high resolution -

Noao Annual Report Fy07

AURA/NOAO ANNUAL REPORT FY 2007 Submitted to the National Science Foundation September 30, 2007 Revised as Final and Submitted January 30, 2008 Emission nebula NGC6334 (Cat’s Paw Nebula): star-forming region in the constellation Scorpius. This 2007 image was taken using the Mosaic-2 imager on the Blanco 4-meter telescope at Cerro Tololo Inter- American Observatory. Intervening dust in the plane of the Milky Way galaxy reddens the colors of the nebula. Image credit: T.A. Rector/University of Alaska Anchorage, T. Abbott and NOAO/AURA/NSF NATIONAL OPTICAL ASTRONOMY OBSERVATORY NOAO ANNUAL REPORT FY 2007 Submitted to the National Science Foundation September 30, 2007 Revised as Final and Submitted January 30, 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................. 1 1 SCIENTIFIC ACTIVITIES AND FINDINGS ..................................................................................... 2 1.1 NOAO Gemini Science Center .............................................................................. 2 GNIRS Infrared Spectroscopy and the Origins of the Peculiar Hydrogen-Deficient Stars...................... 2 Supermassive Black Hole Growth and Chemical Enrichment in the Early Universe.............................. 4 1.2 Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory (CTIO)................................................ 5 The Nearest Stars....................................................................................................................................... -

Large Scale Structures and Structure Formation

8–1 Large Scale Structures and Structure Formation UWarwick 8–2 The Lumpy Universe So far: treated universe as smooth universe. In reality: Universe contains structures! Last part of this class: 1. What are structures? 2. How can we quantify them? 3. How do structures form? 4. How do structures evolve? Will see that all these questions are deeply connected with parameters of the universe seen so far: 1. H0 2. Ω0, Ωb, Ωm, ΩΛ,... 3. Existence and Nature of Dark Matter UWarwick The Lumpy Universe 1 8–3 Introduction, I (de Lapparent, Geller & Huchra, 1986, limiting mag mB = 15.6) Lumpy universe: spatial distribution of galaxies and greater structures. Observationally: need distance information for many (104) objects = Large redshift surveys ⇒ Review: Strauss & Willick (1995) Redshift survey: Survey of (patch of) sky determining galaxy z and position to predefined magnitude or z. First larger survey: de Lapparent, Geller & Huchra (1986) UWarwick Redshift Surveys 1 8–4 Introduction, II (Strauss, 1999) Classification: 1D-surveys: very deep exposures of small patch of sky, e.g. HST Deep Field, Lockman Hole Survey, Marano Field. 2D-surveys: cover long strip of sky, e.g., CfA-Survey (1.5 100 ), 2dF-Survey (“2 degree Field”). × ◦ 3D-surveys: cover part of the sky, e.g., Sloan Digital Sky Survey. These surveys attempt to go to certain limit in z or m. Other approaches: use pre-existing galaxy catalogues (e.g., QDOT Survey [IRAS galaxies], APM survey,. ). Will concentrate here on the larger surveys based on no other catalogue. UWarwick Redshift Surveys 2 8–5 1D Surveys Hubble Deep Field, courtesy STScI HDF: 150ksec/Filter for 4 HST Filters made in ∼ 1995 December.