The Quint V7.2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Politics of Social Inclusion: Bridging Knowledge and Policies Towards Social Change About CROP

Gabriele Koehler, Alberto D. Cimadamore, Fadia Kiwan, Pedro Manuel Monreal Gonzalez (Eds.) The Politics of Social Inclusion: Bridging Knowledge and Policies Towards Social Change About CROP CROP, the Comparative Research Programme on Poverty, was initiated in 1992, and the CROP Secretariat was officially opened in June 1993 by the Director General of UNESCO, Dr Frederico Mayor. The CROP network comprises scholars engaged in poverty-related research across a variety of academic disciplines and has been coordinated by the CROP Secretariat at the University of Bergen,International Norway. Studies in Poverty Research The CROP series on presents expert research and essential analyses of different aspects of poverty worldwide. By promoting a fuller understanding of the nature, extent, depth, distribution, trends, causes and effects of poverty, this series has contributed to knowledge concerning the reduction and eradication of Frompoverty CROP at global, to GRIP regional, national and local levels. After a process of re-thinking CROP, 2019 marked the beginning of a transition from CROP to GRIP – the Global Research Programme on Inequality. GRIP is a radically interdisciplinary research programme that views inequality as both a fundamental challenge to human well-being and as an impediment to achieving the ambitions of the 2030 Agenda. It aims to facilitate collaboration across disciplines and knowledge systems to promote critical, diverse and inter-disciplinary research on inequality. GRIP will continue to build on the successful collaboration between the University of Bergen and the International Science Council that was developed through thep former Comparative Research Programme on Poverty. For more information contact: GRIP Secretariat Faculty of Social Sciences University of Bergen PO Box 7802 5020 Bergen, Norway. -

Draft Letter of Offer This Document Is Important and Requires Your Immediate Attention

DRAFT LETTER OF OFFER THIS DOCUMENT IS IMPORTANT AND REQUIRES YOUR IMMEDIATE ATTENTION The letter of offer (“Letter of Offer”) will be sent to you as an Equity Shareholder of Gaurav Mercantiles Limited (“Target Company”). If you require any clarifications about the action to be taken, you may consult your stock broker or investment consultant or Manager to the Offer or Registrar to the Offer. In case you have recently sold your equity shares in the Target Company, please hand over the Letter of Offer (as defined hereinafter) and the accompanying Form of Acceptance cum Acknowledgement (“Form of Acceptance”) and Securities Transfer Form(s) to the Member of Stock Exchange through whom the said sale was effected. OPEN OFFER (“OFFER”) BY RAGHAV BAHL Residence: F-3, Sector 40, Noida – 201301, Uttar Pradesh, India; Tel.: +91 120 475 1828; Fax: +91 120 475 1828; E-mail: [email protected]; (hereinafter referred to as the “Acquirer”) ALONG WITH RITU KAPUR Residence: F-3, Sector 40, Noida – 201301, Uttar Pradesh, India; Tel.: .: +91 120 475 1828; Fax: +91 120 475 1828; E-mail: [email protected] MAKE A CASH OFFER TO ACQUIRE UP TO 520,000 (FIVE LAKH TWENTY THOUSAND ONLY) FULLY PAID UP EQUITY SHARES, HAVING FACE VALUE OF INR 10 (INDIAN RUPEES TEN ONLY) EACH (“EQUITY SHARES”), REPRESENTING 26% (TWENTY SIX PERCENT ONLY) OF THE VOTING SHARE CAPITAL OF THE TARGET COMPANY (AS HEREINAFTER DEFINED), FROM THE PUBLIC SHAREHOLDERS OF GAURAV MERCANTILES LIMITED Corporate Identification Number: L74130MH1985PLC176592 Registered Office: 310, Gokul Arcade -

CALIFORNIA's NORTH COAST: a Literary Watershed: Charting the Publications of the Region's Small Presses and Regional Authors

CALIFORNIA'S NORTH COAST: A Literary Watershed: Charting the Publications of the Region's Small Presses and Regional Authors. A Geographically Arranged Bibliography focused on the Regional Small Presses and Local Authors of the North Coast of California. First Edition, 2010. John Sherlock Rare Books and Special Collections Librarian University of California, Davis. 1 Table of Contents I. NORTH COAST PRESSES. pp. 3 - 90 DEL NORTE COUNTY. CITIES: Crescent City. HUMBOLDT COUNTY. CITIES: Arcata, Bayside, Blue Lake, Carlotta, Cutten, Eureka, Fortuna, Garberville Hoopa, Hydesville, Korbel, McKinleyville, Miranda, Myers Flat., Orick, Petrolia, Redway, Trinidad, Whitethorn. TRINITY COUNTY CITIES: Junction City, Weaverville LAKE COUNTY CITIES: Clearlake, Clearlake Park, Cobb, Kelseyville, Lakeport, Lower Lake, Middleton, Upper Lake, Wilbur Springs MENDOCINO COUNTY CITIES: Albion, Boonville, Calpella, Caspar, Comptche, Covelo, Elk, Fort Bragg, Gualala, Little River, Mendocino, Navarro, Philo, Point Arena, Talmage, Ukiah, Westport, Willits SONOMA COUNTY. CITIES: Bodega Bay, Boyes Hot Springs, Cazadero, Cloverdale, Cotati, Forestville Geyserville, Glen Ellen, Graton, Guerneville, Healdsburg, Kenwood, Korbel, Monte Rio, Penngrove, Petaluma, Rohnert Part, Santa Rosa, Sebastopol, Sonoma Vineburg NAPA COUNTY CITIES: Angwin, Calistoga, Deer Park, Rutherford, St. Helena, Yountville MARIN COUNTY. CITIES: Belvedere, Bolinas, Corte Madera, Fairfax, Greenbrae, Inverness, Kentfield, Larkspur, Marin City, Mill Valley, Novato, Point Reyes, Point Reyes Station, Ross, San Anselmo, San Geronimo, San Quentin, San Rafael, Sausalito, Stinson Beach, Tiburon, Tomales, Woodacre II. NORTH COAST AUTHORS. pp. 91 - 120 -- Alphabetically Arranged 2 I. NORTH COAST PRESSES DEL NORTE COUNTY. CRESCENT CITY. ARTS-IN-CORRECTIONS PROGRAM (Crescent City). The Brief Pelican: Anthology of Prison Writing, 1993. 1992 Pelikanesis: Creative Writing Anthology, 1994. 1994 Virtual Pelican: anthology of writing by inmates from Pelican Bay State Prison. -

Annual Report 2019 - 2020

Annual Report 2019 - 2020 CENTRE FOR POLICY RESEARCH Annual Report 2019 – 2020 CENTRE FOR POLICY RESEARCH NEW DELHI CONTENTS 1. Vision Statement 1 2. CPR Governing Board 2 3. CPR Executive Committee 4 4. President’s Report 5 5. Research Publications 8 6. Discussions, Meetings and Seminars/Workshops 9 7. CPR’s Initiatives 13 8. Funded Research Projects 27 9. Faculty News 33 10. Activities of Research Associates 56 11. Library and Information & Dissemination Services 62 12. Computer Unit’s Activities 63 13. Grants 64 14. Tax Exemption for Donations to CPR 64 15. CPR Faculty and Staff 65 VISION STATEMENT * VISION To be a leader among the influential national and international think tanks engaged in the Activities of undertaking public policy research and education for moulding public opinion. * OBJECTIVES 1. The main objectives of the Centre for Policy Research are: a. to promote and conduct research in matters pertaining to b. developing substantive policy options; c. building appropriate theoretical frameworks to guide policy; d. forecasting future scenarios through rigorous policy analyses; e. building a knowledge base in all the disciplines relevant to policy formulation; 2. to plan, promote and provide for education and training in policy planning and management areas, and to organise and facilitate Conferences, Seminars, Study Courses, Lectures and similar activities for the purpose; 3. to provide advisory services to Government, public bodies, private sector or any other institutions including international agencies on matters having a bearing on performance, optimum use of national resources for social and economic betterment; 4. to disseminate information on policy issues and know-how on policy making and related areas by undertaking and providing for the publication of journals, reports, pamphlets and other literature and research papers and books; 5. -

The India Freedom Report

THE INDIA FREEDOM REPORT Media Freedom and Freedom of Expression in 2017 TheHoot.org JOURNALISTS UNDER ATTACK CENSORSHIP, NEWS CENSORSHIP, SELF CENSORSHIP THE CLIMATE FOR FREE SPEECH--A STATE-WISE OVERVIEW SEDITION DEFAMATION INTERNET-RELATED OFFENCES AND DIGITAL CENSORSHIP HATE SPEECH FORCED SPEECH INTERNET SHUTDOWNS RIGHT TO INFORMATION FREE SPEECH IN THE COURTS CENSORSHIP OF THE ARTS 2 MEDIA FREEDOM IN 2017 Journalists under attack The climate for journalism in India grew steadily adverse in 2017. A host of perpetrators made reporters and photographers, even editors, fair game as there were murders, attacks, threats, and cases filed against them for defamation, sedition, and internet- related offences. It was a year in which two journalists were shot at point blank range and killed, and one was hacked to death as police stood by and did not stop the mob. The following statistics have been compiled from The Hoot’s Free Speech Hub monitoring: Ø 3 killings of journalists which can be clearly linked to their journalism Ø 46 attacks Ø 27 cases of police action including detentions, arrests and cases filed. Ø 12 cases of threats These are conservative estimates based on reporting in the English press. The major perpetrators as the data in this report shows tend to be the police and politicians and political workers, followed by right wing activists and other non-state actors Law makers became law breakers as members of parliament and legislatures figured among the perpetrators of attacks or threats. These cases included a minister from UP who threatened to set a journalist on fire, and an MLA from Chirala in Andhra Pradesh and his brother accused of being behind a brutal attack on a magazine journalist. -

The 3Rd Edition of Vdonxt Awards Saw a Spurt in Participation by Ad Agencies, Marketers, Online Publishers and Content Creators

February 1-15, 2019 Volume 7, Issue 15 `100 AND THE WINNERS ARE... The 3rd edition of vdonxt awards saw a spurt in participation by ad agencies, marketers, online publishers and content creators. The Quint came up with a stirring performance. 12 Subs riber o yf not or resale Presenting Partner Silver Partners Bronze Partners Community Partner eol This fortnight... Volume 7, Issue 15 hen it comes to online video, the first thing we, as business media journalists, EDITOR Sreekant Khandekar W think of is digital advertisements in video format – and the investments PUBLISHER February 1-15, 2019 Volume 7, Issue 15 `100 brands make to create and push them towards their target audience. But what the Sreekant Khandekar person next door, or her driver for that matter, thinks of is digital videos that she EXECUTIVE EDITOR AND THE can watch – argh, okay fine… consume! – for leisure, knowledge or work. That’s Ashwini Gangal why the focus of the recently concluded third edition of vdonxt asia, our annual ASSOCIATE EDITOR WINNERS Sunit Roy convention on the business of online video, was on content. ARE... PRODUCTION EXECUTIVE The 3rd edition of vdonxt Andrias Kisku awards saw a spurt in participation by ad agencies, marketers, online By the end of the event, two themes shone through this year: Firstly, when it publishers and ADVERTISING ENQUIRIES content creators. The Quint came up comes to online video content, we’re facing the problem of plenty; there’s just so Shubham Garg with a stirring performance. Presents much to watch, yet not all of it is watchable. -

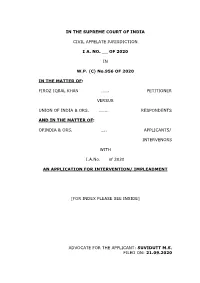

Impleadment Application

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CIVIL APPELATE JURISDICTION I A. NO. __ OF 2020 IN W.P. (C) No.956 OF 2020 IN THE MATTER OF: FIROZ IQBAL KHAN ……. PETITIONER VERSUS UNION OF INDIA & ORS. …….. RESPONDENTS AND IN THE MATTER OF: OPINDIA & ORS. ….. APPLICANTS/ INTERVENORS WITH I.A.No. of 2020 AN APPLICATION FOR INTERVENTION/ IMPLEADMENT [FOR INDEX PLEASE SEE INSIDE] ADVOCATE FOR THE APPLICANT: SUVIDUTT M.S. FILED ON: 21.09.2020 INDEX S.NO PARTICULARS PAGES 1. Application for Intervention/ 1 — 21 Impleadment with Affidavit 2. Application for Exemption from filing 22 – 24 Notarized Affidavit with Affidavit 3. ANNEXURE – A 1 25 – 26 A true copy of the order of this Hon’ble Court in W.P. (C) No.956/ 2020 dated 18.09.2020 4. ANNEXURE – A 2 27 – 76 A true copy the Report titled “A Study on Contemporary Standards in Religious Reporting by Mass Media” 1 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CIVIL ORIGINAL JURISDICTION I.A. No. OF 2020 IN WRIT PETITION (CIVIL) No. 956 OF 2020 IN THE MATTER OF: FIROZ IQBAL KHAN ……. PETITIONER VERSUS UNION OF INDIA & ORS. …….. RESPONDENTS AND IN THE MATTER OF: 1. OPINDIA THROUGH ITS AUTHORISED SIGNATORY, C/O AADHYAASI MEDIA & CONTENT SERVICES PVT LTD, DA 16, SFS FLATS, SHALIMAR BAGH, NEW DELHI – 110088 DELHI ….. APPLICANT NO.1 2. INDIC COLLECTIVE TRUST, THROUGH ITS AUTHORISED SIGNATORY, 2 5E, BHARAT GANGA APARTMENTS, MAHALAKSHMI NAGAR, 4TH CROSS STREET, ADAMBAKKAM, CHENNAI – 600 088 TAMIL NADU ….. APPLICANT NO.2 3. UPWORD FOUNDATION, THROUGH ITS AUTHORISED SIGNATORY, L-97/98, GROUND FLOOR, LAJPAT NAGAR-II, NEW DELHI- 110024 DELHI …. -

2010 Joint Conference of the National Popular Culture and American Culture Associations

2010 Joint Conference of the National Popular Culture and American Culture Associations March 31 – April 3, 2010 Rennaisance Grand Hotel St. Louis Delores F. Rauscher, Editor & PCA/ACA Conference Coordinator Jennifer DeFore, Editor & Assistant Coordinator Michigan State University Elna Lim, Wiley-Blackwell Editor Additional information about the PCA/ACA available at www.pcaaca.org 2 Table of Contents The 2009 National Conference Popular Culture Association & American Culture Association Area Chairs ___________________ 5 PCA/ACA Board Members _______________________________ 13 Officers _______________________________________________ 13 Executive Officers ______________________________________ 13 Past & Future Conferences _______________________________ 14 Conference Papers for Sale; Benefits Endowment _____________ 15 Exhibit Hours __________________________________________ 15 Business & Board Meetings _______________________________ 16 Film Screenings ________________________________________ 18 Dinners, Get-Togethers, Receptions, & Tours ________________ 23 Roundtables ___________________________________________ 25 Special Sessions ______________________________________________ 29 Schedule Overview ______________________________________ 33 Saturday ____________________________________________________ 54 Daily Schedule _________________________________________ 77 Wednesday, 12:30 P.M. – 2:00 P.M. ____________________________ 77 Wednesday, 2:30 P.M. – 4:00 P.M. ____________________________ 83 Wednesday, 4:30 P.M. – 6:00 P.M. ____________________________ -

Newsletter 01/09 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 01/09 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 243 - Januar 2009 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 3 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 01/09 (Nr. 243) Januar 2009 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, zwischen zwei Double Features (ein Hallo Laser Hotline Team, liebe Filmfreunde! Film vor Mitternacht, der zweite da- aus Eurem letzten Editorial (Newsletter Nr. 242) meine ich herauszuhören ;-) , dass der Herzlich willkommen zur ersten Ausga- nach) oder dem überlangen gewöhnliche Sammler von Filmen, Musik und be unseres Newsletters im Jahre 2009! AUSTRALIA, den Theo fachmännisch was auch immer, irgendwann auf den Down- Allen unseren guten Vorsätzen für das so aufbereitete, dass es kurz vor Mit- load via Internet angewiesen sein wird. Ich neue Jahr zum Trotz leider wieder mit ternacht eine Pause gab. Immerhin fan- denke (hoffe), nein! Ich verstehe alle Be- fürchtungen, dennoch, solange unsere Gene- etwas Verspätung. Alte Gewohnheiten den sich für alle Filmpakete auch Zu- ration lebt, wird es runde Scheiben geben! los zu werden ist eben nicht so einfach. schauer – wenn auch nicht sehr viele. Glaubt mir! Aber es gilt natürlich wie immer unser Doch aller Anfang ist schwer. Hier wird Das Internet ist im Access-Bereich bei der Leitspruch: “Wir arbeiten daran!” Ein sicherlich bei der nächsten Silvester- doppelten Maximalrate von DVD angelangt, dennoch tun sich alle VOD (video on Gutes hat die kleine Verspätung je- Film-Party die Mundpropaganda zu demand)- Dienste extrem schwer. -

The Hollywood Cinema Industry's Coming of Digital Age: The

The Hollywood Cinema Industry’s Coming of Digital Age: the Digitisation of Visual Effects, 1977-1999 Volume I Rama Venkatasawmy BA (Hons) Murdoch This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Murdoch University 2010 I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. -------------------------------- Rama Venkatasawmy Abstract By 1902, Georges Méliès’s Le Voyage Dans La Lune had already articulated a pivotal function for visual effects or VFX in the cinema. It enabled the visual realisation of concepts and ideas that would otherwise have been, in practical and logistical terms, too risky, expensive or plain impossible to capture, re-present and reproduce on film according to so-called “conventional” motion-picture recording techniques and devices. Since then, VFX – in conjunction with their respective techno-visual means of re-production – have gradually become utterly indispensable to the array of practices, techniques and tools commonly used in filmmaking as such. For the Hollywood cinema industry, comprehensive VFX applications have not only motivated the expansion of commercial filmmaking praxis. They have also influenced the evolution of viewing pleasures and spectatorship experiences. Following the digitisation of their associated technologies, VFX have been responsible for multiplying the strategies of re-presentation and story-telling as well as extending the range of stories that can potentially be told on screen. By the same token, the visual standards of the Hollywood film’s production and exhibition have been growing in sophistication. -

Ekrany 56 Ang Cc21.Indd

Socialist Entertainment Publisher Stowarzyszenie Przyjaciół Czasopisma o Tematyce Audiowizualnej „Ekrany” Wydział Zarządzania i Komunikacji Społecznej Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego w Krakowie Publisher ’s Address ul. Prof. St. Łojasiewicza 4, pok. 3.222 30 ‑348 Kraków e ‑mail: [email protected] www.ekrany.org.pl Editorial Team Miłosz Stelmach (Editor‑in‑Chief) Maciej Peplinski (Guest Editor) Barbara Szczekała (Deputy Editor‑in‑Chief) Michał Lesiak (Editorial Secretary) Marta Stańczyk Kamil Kalbarczyk Academic Board prof. dr hab. Alicja Helman, prof. dr hab. Tadeusz Lubelski, prof. dr hab. Grażyna Stachówna, prof. dr hab. Tadeusz Szczepański, prof. dr hab. Eugeniusz Wilk, prof. dr hab. Andrzej Gwóźdź, prof. dr hab. Andrzej Pitrus, prof. dr hab. Krzysztof Loska, prof. dr hab. Małgorzata Radkiewicz, dr hab. Jacek Ostaszewski, prof. UJ, dr hab. Rafał Syska, prof. UJ, dr hab. Łucja Demby, prof. UJ, dr hab. Joanna Wojnicka, prof. UJ, dr hab. Anna Nacher, prof. UJ Graphic design Katarzyna Konior www.bluemango.pl Typesetting Piotr Kołodziej Proofreading Biuro Tłumaczeń PWN Gedruckt mit Unterstützung des Leibniz‑Instituts für Geschichte und Kultur des östlichen Europa e. V. in Leipzig. Diese Maßnahme wird mitfinanziert durch Steuermittel auf der Grundlage des vom Sächsischen Landtag beschlossenen Haushaltes. Front page image: Pat & Mat, courtesy of Tomáš Eiselt at Patmat Ltd. 4/2020 Table of Contents Reframing Socialist 4 The Cinema We No Longer Feel Ashamed of Cinema | Ewa Mazierska 11 Paradoxes of Popularity | Balázs Varga 18 Socialist -

Appendix 1: Selected Films

Appendix 1: Selected Films The very random selection of films in this appendix may appear to be arbitrary, but it is an attempt to suggest, from a varied collection of titles not otherwise fully covered in this volume, that approaches to the treatment of sex in the cinema can represent a broad church indeed. Not all the films listed below are accomplished – and some are frankly maladroit – but they all have areas of interest in the ways in which they utilise some form of erotic expression. Barbarella (1968, directed by Roger Vadim) This French/Italian adaptation of the witty and transgressive science fiction comic strip embraces its own trash ethos with gusto, and creates an eccentric, utterly arti- ficial world for its foolhardy female astronaut, who Jane Fonda plays as basically a female Candide in space. The film is full of off- kilter sexuality, such as the evil Black Queen played by Anita Pallenberg as a predatory lesbian, while the opening scene features a space- suited figure stripping in zero gravity under the credits to reveal a naked Jane Fonda. Her peekaboo outfits in the film are cleverly designed, but belong firmly to the actress’s pre- feminist persona – although it might be argued that Barbarella herself, rather than being the sexual plaything for men one might imagine, in fact uses men to grant herself sexual gratification. The Blood Rose/La Rose Écorchée (aka Ravaged, 1970, directed by Claude Mulot) The delirious The Blood Rose was trumpeted as ‘The First Sex Horror Film Ever Made’. In its uncut European version, Claude Mulot’s film begins very much like an arthouse movie of the kind made by such directors as Alain Resnais: unortho- dox editing and tricks with time and the film’s chronology are used to destabilise the viewer.