The Politics of Social Inclusion: Bridging Knowledge and Policies Towards Social Change About CROP

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Draft Letter of Offer This Document Is Important and Requires Your Immediate Attention

DRAFT LETTER OF OFFER THIS DOCUMENT IS IMPORTANT AND REQUIRES YOUR IMMEDIATE ATTENTION The letter of offer (“Letter of Offer”) will be sent to you as an Equity Shareholder of Gaurav Mercantiles Limited (“Target Company”). If you require any clarifications about the action to be taken, you may consult your stock broker or investment consultant or Manager to the Offer or Registrar to the Offer. In case you have recently sold your equity shares in the Target Company, please hand over the Letter of Offer (as defined hereinafter) and the accompanying Form of Acceptance cum Acknowledgement (“Form of Acceptance”) and Securities Transfer Form(s) to the Member of Stock Exchange through whom the said sale was effected. OPEN OFFER (“OFFER”) BY RAGHAV BAHL Residence: F-3, Sector 40, Noida – 201301, Uttar Pradesh, India; Tel.: +91 120 475 1828; Fax: +91 120 475 1828; E-mail: [email protected]; (hereinafter referred to as the “Acquirer”) ALONG WITH RITU KAPUR Residence: F-3, Sector 40, Noida – 201301, Uttar Pradesh, India; Tel.: .: +91 120 475 1828; Fax: +91 120 475 1828; E-mail: [email protected] MAKE A CASH OFFER TO ACQUIRE UP TO 520,000 (FIVE LAKH TWENTY THOUSAND ONLY) FULLY PAID UP EQUITY SHARES, HAVING FACE VALUE OF INR 10 (INDIAN RUPEES TEN ONLY) EACH (“EQUITY SHARES”), REPRESENTING 26% (TWENTY SIX PERCENT ONLY) OF THE VOTING SHARE CAPITAL OF THE TARGET COMPANY (AS HEREINAFTER DEFINED), FROM THE PUBLIC SHAREHOLDERS OF GAURAV MERCANTILES LIMITED Corporate Identification Number: L74130MH1985PLC176592 Registered Office: 310, Gokul Arcade -

The Quint V7.2

the quint : an interdisciplinary quarterly from the north 1 contents the quint volume seven issue two EDITORIAL an interdisciplinary quarterly from "Tick -Tock" by Lydia Craig........................................................................................................6 Ditch #1 by Anne Jevne.............................................................................................................8 the north (Post)modernism and Globalization byHaidar Eid....................................................................9 advisory board Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds by Virginia Konchan.............................................................23 Dr. Keith Batterbe ISSN 1920–1028 Ditch #2 by Anne Jevne............................................................................................................24 University of Turku e Autonomous Mind of Waskechak by John George Hansen.................................................25 Dr. Lynn Ecchevarria Raised by His Grandmother Legend: Child of Caribou by Simon Samuel................................44 Yukon College Ditch #3 by Anne Jevne...........................................................................................................50 Dr. Susan Gold the quint welcomes submissions. See our guidelines Milton in Canada: Ideal, Ghost or Inspiration? by Martin Kuester.........................................51 University of Windsor or contact us at: Die Walküre by Virginia Konchan..........................................................................................75 -

Annual Report 2019 - 2020

Annual Report 2019 - 2020 CENTRE FOR POLICY RESEARCH Annual Report 2019 – 2020 CENTRE FOR POLICY RESEARCH NEW DELHI CONTENTS 1. Vision Statement 1 2. CPR Governing Board 2 3. CPR Executive Committee 4 4. President’s Report 5 5. Research Publications 8 6. Discussions, Meetings and Seminars/Workshops 9 7. CPR’s Initiatives 13 8. Funded Research Projects 27 9. Faculty News 33 10. Activities of Research Associates 56 11. Library and Information & Dissemination Services 62 12. Computer Unit’s Activities 63 13. Grants 64 14. Tax Exemption for Donations to CPR 64 15. CPR Faculty and Staff 65 VISION STATEMENT * VISION To be a leader among the influential national and international think tanks engaged in the Activities of undertaking public policy research and education for moulding public opinion. * OBJECTIVES 1. The main objectives of the Centre for Policy Research are: a. to promote and conduct research in matters pertaining to b. developing substantive policy options; c. building appropriate theoretical frameworks to guide policy; d. forecasting future scenarios through rigorous policy analyses; e. building a knowledge base in all the disciplines relevant to policy formulation; 2. to plan, promote and provide for education and training in policy planning and management areas, and to organise and facilitate Conferences, Seminars, Study Courses, Lectures and similar activities for the purpose; 3. to provide advisory services to Government, public bodies, private sector or any other institutions including international agencies on matters having a bearing on performance, optimum use of national resources for social and economic betterment; 4. to disseminate information on policy issues and know-how on policy making and related areas by undertaking and providing for the publication of journals, reports, pamphlets and other literature and research papers and books; 5. -

The India Freedom Report

THE INDIA FREEDOM REPORT Media Freedom and Freedom of Expression in 2017 TheHoot.org JOURNALISTS UNDER ATTACK CENSORSHIP, NEWS CENSORSHIP, SELF CENSORSHIP THE CLIMATE FOR FREE SPEECH--A STATE-WISE OVERVIEW SEDITION DEFAMATION INTERNET-RELATED OFFENCES AND DIGITAL CENSORSHIP HATE SPEECH FORCED SPEECH INTERNET SHUTDOWNS RIGHT TO INFORMATION FREE SPEECH IN THE COURTS CENSORSHIP OF THE ARTS 2 MEDIA FREEDOM IN 2017 Journalists under attack The climate for journalism in India grew steadily adverse in 2017. A host of perpetrators made reporters and photographers, even editors, fair game as there were murders, attacks, threats, and cases filed against them for defamation, sedition, and internet- related offences. It was a year in which two journalists were shot at point blank range and killed, and one was hacked to death as police stood by and did not stop the mob. The following statistics have been compiled from The Hoot’s Free Speech Hub monitoring: Ø 3 killings of journalists which can be clearly linked to their journalism Ø 46 attacks Ø 27 cases of police action including detentions, arrests and cases filed. Ø 12 cases of threats These are conservative estimates based on reporting in the English press. The major perpetrators as the data in this report shows tend to be the police and politicians and political workers, followed by right wing activists and other non-state actors Law makers became law breakers as members of parliament and legislatures figured among the perpetrators of attacks or threats. These cases included a minister from UP who threatened to set a journalist on fire, and an MLA from Chirala in Andhra Pradesh and his brother accused of being behind a brutal attack on a magazine journalist. -

The 3Rd Edition of Vdonxt Awards Saw a Spurt in Participation by Ad Agencies, Marketers, Online Publishers and Content Creators

February 1-15, 2019 Volume 7, Issue 15 `100 AND THE WINNERS ARE... The 3rd edition of vdonxt awards saw a spurt in participation by ad agencies, marketers, online publishers and content creators. The Quint came up with a stirring performance. 12 Subs riber o yf not or resale Presenting Partner Silver Partners Bronze Partners Community Partner eol This fortnight... Volume 7, Issue 15 hen it comes to online video, the first thing we, as business media journalists, EDITOR Sreekant Khandekar W think of is digital advertisements in video format – and the investments PUBLISHER February 1-15, 2019 Volume 7, Issue 15 `100 brands make to create and push them towards their target audience. But what the Sreekant Khandekar person next door, or her driver for that matter, thinks of is digital videos that she EXECUTIVE EDITOR AND THE can watch – argh, okay fine… consume! – for leisure, knowledge or work. That’s Ashwini Gangal why the focus of the recently concluded third edition of vdonxt asia, our annual ASSOCIATE EDITOR WINNERS Sunit Roy convention on the business of online video, was on content. ARE... PRODUCTION EXECUTIVE The 3rd edition of vdonxt Andrias Kisku awards saw a spurt in participation by ad agencies, marketers, online By the end of the event, two themes shone through this year: Firstly, when it publishers and ADVERTISING ENQUIRIES content creators. The Quint came up comes to online video content, we’re facing the problem of plenty; there’s just so Shubham Garg with a stirring performance. Presents much to watch, yet not all of it is watchable. -

Impleadment Application

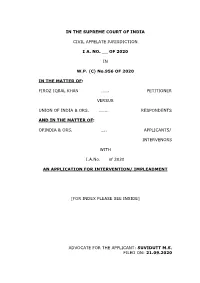

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CIVIL APPELATE JURISDICTION I A. NO. __ OF 2020 IN W.P. (C) No.956 OF 2020 IN THE MATTER OF: FIROZ IQBAL KHAN ……. PETITIONER VERSUS UNION OF INDIA & ORS. …….. RESPONDENTS AND IN THE MATTER OF: OPINDIA & ORS. ….. APPLICANTS/ INTERVENORS WITH I.A.No. of 2020 AN APPLICATION FOR INTERVENTION/ IMPLEADMENT [FOR INDEX PLEASE SEE INSIDE] ADVOCATE FOR THE APPLICANT: SUVIDUTT M.S. FILED ON: 21.09.2020 INDEX S.NO PARTICULARS PAGES 1. Application for Intervention/ 1 — 21 Impleadment with Affidavit 2. Application for Exemption from filing 22 – 24 Notarized Affidavit with Affidavit 3. ANNEXURE – A 1 25 – 26 A true copy of the order of this Hon’ble Court in W.P. (C) No.956/ 2020 dated 18.09.2020 4. ANNEXURE – A 2 27 – 76 A true copy the Report titled “A Study on Contemporary Standards in Religious Reporting by Mass Media” 1 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CIVIL ORIGINAL JURISDICTION I.A. No. OF 2020 IN WRIT PETITION (CIVIL) No. 956 OF 2020 IN THE MATTER OF: FIROZ IQBAL KHAN ……. PETITIONER VERSUS UNION OF INDIA & ORS. …….. RESPONDENTS AND IN THE MATTER OF: 1. OPINDIA THROUGH ITS AUTHORISED SIGNATORY, C/O AADHYAASI MEDIA & CONTENT SERVICES PVT LTD, DA 16, SFS FLATS, SHALIMAR BAGH, NEW DELHI – 110088 DELHI ….. APPLICANT NO.1 2. INDIC COLLECTIVE TRUST, THROUGH ITS AUTHORISED SIGNATORY, 2 5E, BHARAT GANGA APARTMENTS, MAHALAKSHMI NAGAR, 4TH CROSS STREET, ADAMBAKKAM, CHENNAI – 600 088 TAMIL NADU ….. APPLICANT NO.2 3. UPWORD FOUNDATION, THROUGH ITS AUTHORISED SIGNATORY, L-97/98, GROUND FLOOR, LAJPAT NAGAR-II, NEW DELHI- 110024 DELHI …. -

What If Scale Breaks Community? Rebooting Audience Engagement When Journalism Is Under Fire

What if Scale Breaks Community? Rebooting Audience Engagement When Journalism is Under Fire Julie Posetti, Felix Simon, and Nabeelah Shabbir JOURNALISM INNOVATION PROJECT • OCTOBER 2019 Cover photos by Julie Posetti What if Scale Breaks Community? Rebooting Audience Engagement When Journalism is Under Fire Julie Posetti, Felix Simon, and Nabeelah Shabbir Published by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism with the support of the Facebook Journalism Project. All data was correct at the time of production. Declaration: The CEOs of Rappler (Maria Ressa) and The Quint (Ritu Kapur) now sit on RISJ’s Advisory Board. WHAT IF SCALE BREAKS COMMUNITY? Contents About the Authors 7 Acknowledgements 7 Executive Summary and Key Findings 8 1. Introduction 10 2. Engagement Evolution: Reimagining Audiences Amidst Upheaval 15 3. Engagement Transitions in Response to External Threats and Audience ‘Toxicity’ 25 4. Early Lessons from the Move to Membership 37 5. Conclusion 46 Appendix: List of Interviewees 48 References 49 5 THE REUTERS INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF JOURNALISM WHAT IF SCALE BREAKS COMMUNITY? About the Authors Dr Julie Posetti is Global Director of Research at the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ), Senior Researcher at Sheffield University’s Centre for Freedom of the Media, and Research Associate at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (RISJ) at the University of Oxford, where she led the Journalism Innovation Project from 2018 to 2019. Dr. Posetti authored Protecting Journalism Sources in the Digital Age (UNESCO 2017), and co-authored Journalism, ‘Fake News’ and Disinformation (Ireton & Posetti 2018). She is also lead author of the Perugia Principles for Journalists: Working with Whistleblowers in the Digital Age (2019). -

Digital Journalism Start-Ups in India (P Ilbu Sh Tniojde Llyy Iw Tthh I

REUTERS INSTITUTE for the STUDY of SELECTED RISJ PUBLICCATIONSATIONSS REPORT JOURNALISM Abdalla Hassan Raymond Kuhn and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen (eds) Media, Reevvolution, and Politics in Egyyppt: The Story of an Po lacitil Journalism in Transition: Western Europe in a Uprising Comparative Perspective (published jointllyy iw tthh I.B.Tau s)ri (published tnioj llyy htiw I.B.Tau s)ri Robert G. Picard (ed.) Nigel Bowles, James T. Hamilton, David A. L. Levvyy )sde( The Euro Crisis in the Media: Journalistic Coverage of Transparenccyy in Politics and the Media: Accountability and Economic Crisis and European Institutions Open Government (published jointllyy iw tthh I.B.Tauris) (published tnioj llyy htiw I.B.Tau s)ri Rasmus Kleis Nielsen (ed.) Julian Pettl ye (e ).d Loc Jla naour lism: The Decli ofne News pepa rs and the Media and Public Shaming: Drawing the Boundaries of Rise of Digital Media Di usolcs re Digital Journalism Start-Ups in India (published jointllyy iw tthh I.B.Tau s)ri (publ(publ si heed joi tn llyy tiw h II.. T.B aur )si Wendy N. Wy de(tta .) La ar Fi le dden The Ethics of Journalism: Individual, stIn itutional and Regulating ffoor Trust in Journalism: Standards Regulation Cu nIlarutl fflluences in the Age of Blended Media (published jointllyy iw tthh I.B.Tau s)ri Arijit Sen and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen David A. L eL. vvyy and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen (eds) The Changing Business of Journalism and its Implications for Demo arc ccyy May 2016 CHALLENGES Robert G. Picard and Hannah Storm Nick Fras re The Kidnapping of Journalists: Reporting -

The Politi of Social Inclusion

CROP International Poverty Studies, vol. 9 CROP Koehler et al. (eds.) The Politi of Social Inclusion: Bridging Knowledge and Policies Towards Social Change Social Towards Bridging Knowledge and Policies Inclusion: of Social et al. (eds.) The Politi The Politi of Social Inclusion: Bridging Knowledge and Policies Towards Social Change Edited by Gabriele Koehler, Alberto D Cimadamore, Fadia Kiwan, Pedro Manuel Monreal Gonzalez ISBN: 978-3-8382-1333-0 ibidem ibidem Gabriele Koehler, Alberto D. Cimadamore, Fadia Kiwan, Pedro Manuel Monreal Gonzalez (Eds.) The Politics of Social Inclusion: Bridging Knowledge and Policies Towards Social Change About CROP CROP, the Comparative Research Programme on Poverty, was initiated in 1992, and the CROP Secretariat was officially opened in June 1993 by the Director General of UNESCO, Dr Frederico Mayor. The CROP network comprises scholars engaged in poverty-related research across a variety of academic disciplines and has been coordinated by the CROP Secretariat at the University of Bergen,International Norway. Studies in Poverty Research The CROP series on presents expert research and essential analyses of different aspects of poverty worldwide. By promoting a fuller understanding of the nature, extent, depth, distribution, trends, causes and effects of poverty, this series has contributed to knowledge concerning the reduction and eradication of Frompoverty CROP at global, to GRIP regional, national and local levels. After a process of re-thinking CROP, 2019 marked the beginning of a transition from CROP to GRIP – the Global Research Programme on Inequality. GRIP is a radically interdisciplinary research programme that views inequality as both a fundamental challenge to human well-being and as an impediment to achieving the ambitions of the 2030 Agenda. -

India's War on Sikh Social Media July, 2020 July 20, 2020 World Sikh Organization of Canada

World Sikh Organization of Canada Enforcing silence: India's War on Sikh Social Media July, 2020 July 20, 2020 World Sikh Organization of Canada Introduction and Insights Indian authorities are increasingly using social media to target and prosecute Sikhs and members of other minority communities who advocate on human rights and political issues. Social media posts deemed critical of India or supportive of separatist movements are reported for removal and in some cases, lead to individuals being detained and charged for terrorism related offences. In particular, Sikhs expressing support for Khalistan are being targeted. Since June 2020, hundreds of Sikhs have been detained and interrogated in India due to their social media activities and some have been charged with offences related to support for Khalistan under the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (“UAPA”). Likewise, social media content that India deems offensive, particularly in relation to Khalistan, is being reported and flagged for removal on a wide scale. Khalistan refers to a sovereign state governed in accordance with Sikh principles and values. Khalistan is a construct that is understood in different ways and is a source of robust discourse and debate amongst Sikhs worldwide. Discussing or promoting Khalistan is within recognized freedoms of expression and political discourse and should not be confused with extremism or terrorism. However, Indian authorities attempt to marginalize and repress dissenting voices through draconian anti-terror laws such as the UAPA. Legitimate political expression that India finds objectionable or threatening is branded as extremism and those expressing such views are targeted by the State. World Sikh Organization of Canada Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA) The UAPA is draconian law allows authorities to arrest and jail individuals for years at a time without a trial. -

Understanding Violence Against Women in Rural Haryana

INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS INTERNSHIP PROGRAM | WORKING PAPER SERIES VOL. 9 | NO. 1 | SUMMER 2020 Consent, Creditability, and Coercion: Understanding Violence Against Women in Rural Haryana Mahima Kapur ABOUT CHRLP Established in September 2005, the Centre for Human Rights and Legal Pluralism (CHRLP) was formed to provide students, professors and the larger community with a locus of intellectual and physical resources for engaging critically with the ways in which law affects some of the most compelling social problems of our modern era, most notably human rights issues. Since then, the Centre has distinguished itself by its innovative legal and interdisciplinary approach, and its diverse and vibrant community of scholars, students and practitioners working at the intersection of human rights and legal pluralism. – 2 – CHRLP is a focal point for innovative legal and interdisciplinary research, dialogue and outreach on issues of human rights and legal pluralism. The Centre’s mission is to provide students, professors and the wider community with a locus of intellectual and physical resources for engaging critically with how law impacts upon some of the compelling social problems of our modern era. A key objective of the Centre is to deepen transdisciplinary collaboration on the complex social, ethical, political and philosophical dimensions of human rights. The current Centre initiative builds upon the human rights legacy and enormous scholarly engagement found in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. ABOUT THE SERIES The Centre for Human Rights and Legal Pluralism (CHRLP) Working Paper Series enables the dissemination of papers by students who have participated in the Centre’s International Human Rights Internship Program (IHRIP). -

The Contagion of Hate in India

THE CONTAGION OF HATE IN INDIA By Laxmi Murthy Laxmi Murthy is a journalist based in Bangalore, India. Introduction The COVID-19 pandemic that began its sweep This paper attempts to understand the pheno- across the globe in early 2020 has had a menon of hate speech and its potential to devastating effect not only on health, life legitimise discrimination and promote violence and livelihoods, but on the fabric of society against its targets. It lays out the interconnections itself. As with all moments of social crisis, it between Islamophobia, hate speech and acts has deepened existing cleavages, as well as of physical violence against Muslims. The role dented and even demolished already fragile of social media, especially messaging platforms secular democratic structures. While social and like WhatsApp and Facebook, in facilitating economic marginalisation has sharpened, one the easy and rapid spread of fake news and of the starkest consequences has been the rumours and amplifying hate, is also examined. naturalisation of hatred towards India’s largest The complexities of regulating social media minority community. Along with the spread platforms, which have immense political and of COVID-19, Islamophobia spiked and spread corporate backing, have been touched upon. rapidly into every sphere of life. From calls to This paper also looks at the contentious and marginalise,1 isolate,2 segregate3 and boycott contradictory interplay of hate speech with the Muslim communities, to sanctioning the use of constitutionally guaranteed freedom of speech force, hateful prejudice peaked and spilled over and expression and recent jurisprudence on these into violence. An already beleaguered Muslim matters.