Self-Referencing the News

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Politics of Social Inclusion: Bridging Knowledge and Policies Towards Social Change About CROP

Gabriele Koehler, Alberto D. Cimadamore, Fadia Kiwan, Pedro Manuel Monreal Gonzalez (Eds.) The Politics of Social Inclusion: Bridging Knowledge and Policies Towards Social Change About CROP CROP, the Comparative Research Programme on Poverty, was initiated in 1992, and the CROP Secretariat was officially opened in June 1993 by the Director General of UNESCO, Dr Frederico Mayor. The CROP network comprises scholars engaged in poverty-related research across a variety of academic disciplines and has been coordinated by the CROP Secretariat at the University of Bergen,International Norway. Studies in Poverty Research The CROP series on presents expert research and essential analyses of different aspects of poverty worldwide. By promoting a fuller understanding of the nature, extent, depth, distribution, trends, causes and effects of poverty, this series has contributed to knowledge concerning the reduction and eradication of Frompoverty CROP at global, to GRIP regional, national and local levels. After a process of re-thinking CROP, 2019 marked the beginning of a transition from CROP to GRIP – the Global Research Programme on Inequality. GRIP is a radically interdisciplinary research programme that views inequality as both a fundamental challenge to human well-being and as an impediment to achieving the ambitions of the 2030 Agenda. It aims to facilitate collaboration across disciplines and knowledge systems to promote critical, diverse and inter-disciplinary research on inequality. GRIP will continue to build on the successful collaboration between the University of Bergen and the International Science Council that was developed through thep former Comparative Research Programme on Poverty. For more information contact: GRIP Secretariat Faculty of Social Sciences University of Bergen PO Box 7802 5020 Bergen, Norway. -

Draft Letter of Offer This Document Is Important and Requires Your Immediate Attention

DRAFT LETTER OF OFFER THIS DOCUMENT IS IMPORTANT AND REQUIRES YOUR IMMEDIATE ATTENTION The letter of offer (“Letter of Offer”) will be sent to you as an Equity Shareholder of Gaurav Mercantiles Limited (“Target Company”). If you require any clarifications about the action to be taken, you may consult your stock broker or investment consultant or Manager to the Offer or Registrar to the Offer. In case you have recently sold your equity shares in the Target Company, please hand over the Letter of Offer (as defined hereinafter) and the accompanying Form of Acceptance cum Acknowledgement (“Form of Acceptance”) and Securities Transfer Form(s) to the Member of Stock Exchange through whom the said sale was effected. OPEN OFFER (“OFFER”) BY RAGHAV BAHL Residence: F-3, Sector 40, Noida – 201301, Uttar Pradesh, India; Tel.: +91 120 475 1828; Fax: +91 120 475 1828; E-mail: [email protected]; (hereinafter referred to as the “Acquirer”) ALONG WITH RITU KAPUR Residence: F-3, Sector 40, Noida – 201301, Uttar Pradesh, India; Tel.: .: +91 120 475 1828; Fax: +91 120 475 1828; E-mail: [email protected] MAKE A CASH OFFER TO ACQUIRE UP TO 520,000 (FIVE LAKH TWENTY THOUSAND ONLY) FULLY PAID UP EQUITY SHARES, HAVING FACE VALUE OF INR 10 (INDIAN RUPEES TEN ONLY) EACH (“EQUITY SHARES”), REPRESENTING 26% (TWENTY SIX PERCENT ONLY) OF THE VOTING SHARE CAPITAL OF THE TARGET COMPANY (AS HEREINAFTER DEFINED), FROM THE PUBLIC SHAREHOLDERS OF GAURAV MERCANTILES LIMITED Corporate Identification Number: L74130MH1985PLC176592 Registered Office: 310, Gokul Arcade -

The Quint V7.2

the quint : an interdisciplinary quarterly from the north 1 contents the quint volume seven issue two EDITORIAL an interdisciplinary quarterly from "Tick -Tock" by Lydia Craig........................................................................................................6 Ditch #1 by Anne Jevne.............................................................................................................8 the north (Post)modernism and Globalization byHaidar Eid....................................................................9 advisory board Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds by Virginia Konchan.............................................................23 Dr. Keith Batterbe ISSN 1920–1028 Ditch #2 by Anne Jevne............................................................................................................24 University of Turku e Autonomous Mind of Waskechak by John George Hansen.................................................25 Dr. Lynn Ecchevarria Raised by His Grandmother Legend: Child of Caribou by Simon Samuel................................44 Yukon College Ditch #3 by Anne Jevne...........................................................................................................50 Dr. Susan Gold the quint welcomes submissions. See our guidelines Milton in Canada: Ideal, Ghost or Inspiration? by Martin Kuester.........................................51 University of Windsor or contact us at: Die Walküre by Virginia Konchan..........................................................................................75 -

Annual Report 2019 - 2020

Annual Report 2019 - 2020 CENTRE FOR POLICY RESEARCH Annual Report 2019 – 2020 CENTRE FOR POLICY RESEARCH NEW DELHI CONTENTS 1. Vision Statement 1 2. CPR Governing Board 2 3. CPR Executive Committee 4 4. President’s Report 5 5. Research Publications 8 6. Discussions, Meetings and Seminars/Workshops 9 7. CPR’s Initiatives 13 8. Funded Research Projects 27 9. Faculty News 33 10. Activities of Research Associates 56 11. Library and Information & Dissemination Services 62 12. Computer Unit’s Activities 63 13. Grants 64 14. Tax Exemption for Donations to CPR 64 15. CPR Faculty and Staff 65 VISION STATEMENT * VISION To be a leader among the influential national and international think tanks engaged in the Activities of undertaking public policy research and education for moulding public opinion. * OBJECTIVES 1. The main objectives of the Centre for Policy Research are: a. to promote and conduct research in matters pertaining to b. developing substantive policy options; c. building appropriate theoretical frameworks to guide policy; d. forecasting future scenarios through rigorous policy analyses; e. building a knowledge base in all the disciplines relevant to policy formulation; 2. to plan, promote and provide for education and training in policy planning and management areas, and to organise and facilitate Conferences, Seminars, Study Courses, Lectures and similar activities for the purpose; 3. to provide advisory services to Government, public bodies, private sector or any other institutions including international agencies on matters having a bearing on performance, optimum use of national resources for social and economic betterment; 4. to disseminate information on policy issues and know-how on policy making and related areas by undertaking and providing for the publication of journals, reports, pamphlets and other literature and research papers and books; 5. -

India 2020 in Review

The impact of COVID-19 on older persons in India 2020 in review Highlights • India reported its first COVID-19 case on 30 January 2020 and its first COVID-19 death on 13 March 2020.1 As on 08 December 2020 India has the second highest number of reported cases of COVID-19 in the world and the third highest number of deaths due to COVID-19 globally.2 However, in terms of per capita mortality rate India is only 78th globally with 9.43 deaths per 100,000 population.3 • The Government of India (GoI) announced a countrywide lockdown from 25 March – 31 May 2020, after which restrictions were eased in a phased manner.4 • As per estimates on 13 October 2020 53 per cent of the deaths have occurred in the age group of 60 and above,5 though they accounted for only 12 per cent of COVID-19 positive cases as per data released in September.6 • A nation-wide survey of older persons in June 2020 indicated that the pandemic has adversely impacted the livelihoods of roughly 65 per cent of the participants. • An independent survey conducted in April 2020 concluded that 51 per cent of older persons surveyed were reported to have been physically or mentally mistreated during the pandemic.7 • India’s real GDP growth rate is expected to decline from 4.2 per cent in 2019 to –10.3 per cent in 2020.8 Data released by the National Statistical Office indicates that India has technically entered a recession, with the GDP of India declining by 7.5 per cent in the July- September quarter (Q2),9 following 23.9 per cent in the April-June quarter (Q1).10 • It is estimated that 400 million workers from India’s informal sector (of which 11 million are expected to be older persons) are likely to be pushed into extreme poverty.11 12 • The COVID-19 lockdown has impacted the livelihoods of a large proportion of the country’s nearly 40 million internal migrants.13 A majority of these migrant workers are daily wage labourers, who were stranded after the lockdown and started fleeing from cities to their native places. -

The India Freedom Report

THE INDIA FREEDOM REPORT Media Freedom and Freedom of Expression in 2017 TheHoot.org JOURNALISTS UNDER ATTACK CENSORSHIP, NEWS CENSORSHIP, SELF CENSORSHIP THE CLIMATE FOR FREE SPEECH--A STATE-WISE OVERVIEW SEDITION DEFAMATION INTERNET-RELATED OFFENCES AND DIGITAL CENSORSHIP HATE SPEECH FORCED SPEECH INTERNET SHUTDOWNS RIGHT TO INFORMATION FREE SPEECH IN THE COURTS CENSORSHIP OF THE ARTS 2 MEDIA FREEDOM IN 2017 Journalists under attack The climate for journalism in India grew steadily adverse in 2017. A host of perpetrators made reporters and photographers, even editors, fair game as there were murders, attacks, threats, and cases filed against them for defamation, sedition, and internet- related offences. It was a year in which two journalists were shot at point blank range and killed, and one was hacked to death as police stood by and did not stop the mob. The following statistics have been compiled from The Hoot’s Free Speech Hub monitoring: Ø 3 killings of journalists which can be clearly linked to their journalism Ø 46 attacks Ø 27 cases of police action including detentions, arrests and cases filed. Ø 12 cases of threats These are conservative estimates based on reporting in the English press. The major perpetrators as the data in this report shows tend to be the police and politicians and political workers, followed by right wing activists and other non-state actors Law makers became law breakers as members of parliament and legislatures figured among the perpetrators of attacks or threats. These cases included a minister from UP who threatened to set a journalist on fire, and an MLA from Chirala in Andhra Pradesh and his brother accused of being behind a brutal attack on a magazine journalist. -

Government Advertising As an Indicator of Media Bias in India

Sciences Po Paris Government Advertising as an Indicator of Media Bias in India by Prateek Sibal A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment for the degree of Master in Public Policy under the guidance of Prof. Julia Cage Department of Economics May 2018 Declaration of Authorship I, Prateek Sibal, declare that this thesis titled, 'Government Advertising as an Indicator of Media Bias in India' and the work presented in it are my own. I confirm that: This work was done wholly or mainly while in candidature for Masters in Public Policy at Sciences Po, Paris. Where I have consulted the published work of others, this is always clearly attributed. Where I have quoted from the work of others, the source is always given. With the exception of such quotations, this thesis is entirely my own work. I have acknowledged all main sources of help. Signed: Date: iii Abstract by Prateek Sibal School of Public Affairs Sciences Po Paris Freedom of the press is inextricably linked to the economics of news media busi- ness. Many media organizations rely on advertisements as their main source of revenue, making them vulnerable to interference from advertisers. In India, the Government is a major advertiser in newspapers. Interviews with journalists sug- gest that governments in India actively interfere in working of the press, through both economic blackmail and misuse of regulation. However, it is difficult to gauge the media bias that results due to government pressure. This paper determines a newspaper's bias based on the change in advertising spend share per newspa- per before and after 2014 general election. -

Mahindra Everyday

ISSUE 1, 2013 ISSUE 1, 2013 WHAT’S INSIDE? Mahindra e2o Launched: Set to Redefine the Future of Mobility World Class Tractor Plant Inaugurated in Andhra Pradesh MSSSPL’s Golden Journey Of 50 Years 8th Annual Mahindra Excellence in Theatre Awards Announced Special Feature: The Mahindra Institute of Quality Mahindra Everyday 1 ISSUE 1, 2013 CONTENTS CULTURAL COVER STORY 04 OUTREACH 35 Mahindra USA’s exciting and eventful On the art and culture front, initiatives story of growth and success, from showcased old world culture, the world’s 1994 to date. best guitar and music talent, excellence in theatre and more. INTERNATIONAL AWARDS FOR OPERATIONS 11 EXCELLENCE 40 The Mahindra Group’s international A spectrum of awards, including the action stretched from Serbia to Sri first Mahindra Sustainability awards Lanka, South Africa and elsewhere recognising diverse sustainability around the globe. initiatives, was recently presented. SECTOR BRIEFS 13 SUSTAINABILITY 47 As ever there was plenty happening Efforts and initiatives towards across sectors and in all spheres of preserving, safeguarding and sustaining action – new plants, new products, our planet and its precious resources. distinguished visitors, certifications and celebrations. Please write in to [email protected] to give feedback on this issue. ME TEAM Associate Editors: Zarina Hodiwalla, Darius Lam Soumi Rao Chandrika Rodrigues Col. Abhijit Dasgupta AS, Kandivli MLDL Mahindra Management Dev. Center Asha Sabharwal Stella Rozario AS, Nashik MTWL Santosh Tandav Mahindra Partners Shirish Kulkarni Pradeep Zoting AS, Igatpuri FES, Nagpur Vrinda Pisharody Tech Mahindra & K.P. Narsimha Rao Pavitra Kamdadai Mahindra Satyam AS, Zaheerabad MNEPL Rajeev Malik Venecia Paulose Martin Cisneros Preeti Nair MVML, Chakan Mahindra USA Mahindra Navistar Edited and Published by Roma Balwani Nitin Panday Swapnil Soudagar Pooja Thawrani for Mahindra & Mahindra Limited, Gateway Mahindra Swaraj Systech Mahindra Reva Building, Apollo Bunder, Mumbai 400 001. -

The 3Rd Edition of Vdonxt Awards Saw a Spurt in Participation by Ad Agencies, Marketers, Online Publishers and Content Creators

February 1-15, 2019 Volume 7, Issue 15 `100 AND THE WINNERS ARE... The 3rd edition of vdonxt awards saw a spurt in participation by ad agencies, marketers, online publishers and content creators. The Quint came up with a stirring performance. 12 Subs riber o yf not or resale Presenting Partner Silver Partners Bronze Partners Community Partner eol This fortnight... Volume 7, Issue 15 hen it comes to online video, the first thing we, as business media journalists, EDITOR Sreekant Khandekar W think of is digital advertisements in video format – and the investments PUBLISHER February 1-15, 2019 Volume 7, Issue 15 `100 brands make to create and push them towards their target audience. But what the Sreekant Khandekar person next door, or her driver for that matter, thinks of is digital videos that she EXECUTIVE EDITOR AND THE can watch – argh, okay fine… consume! – for leisure, knowledge or work. That’s Ashwini Gangal why the focus of the recently concluded third edition of vdonxt asia, our annual ASSOCIATE EDITOR WINNERS Sunit Roy convention on the business of online video, was on content. ARE... PRODUCTION EXECUTIVE The 3rd edition of vdonxt Andrias Kisku awards saw a spurt in participation by ad agencies, marketers, online By the end of the event, two themes shone through this year: Firstly, when it publishers and ADVERTISING ENQUIRIES content creators. The Quint came up comes to online video content, we’re facing the problem of plenty; there’s just so Shubham Garg with a stirring performance. Presents much to watch, yet not all of it is watchable. -

Coronajihad: COVID-19, Misinformation, and Anti-Muslim Violence in India

#CoronaJihad COVID-19, Misinformation, and Anti-Muslim Violence in India Shweta Desai and Amarnath Amarasingam Abstract About the authors On March 25th, India imposed one of the largest Shweta Desai is an independent researcher and lockdowns in history, confining its 1.3 billion journalist based between India and France. She is citizens for over a month to contain the spread of interested in terrorism, jihadism, religious extremism the novel coronavirus (COVID-19). By the end of and armed conflicts. the first week of the lockdown, starting March 29th reports started to emerge that there was a common Amarnath Amarasingam is an Assistant Professor in link among a large number of the new cases the School of Religion at Queen’s University in Ontario, detected in different parts of the country: many had Canada. He is also a Senior Research Fellow at the attended a large religious gathering of Muslims in Institute for Strategic Dialogue, an Associate Fellow at Delhi. In no time, Hindu nationalist groups began to the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation, see the virus not as an entity spreading organically and an Associate Fellow at the Global Network on throughout India, but as a sinister plot by Indian Extremism and Technology. His research interests Muslims to purposefully infect the population. This are in radicalization, terrorism, diaspora politics, post- report tracks anti-Muslim rhetoric and violence in war reconstruction, and the sociology of religion. He India related to COVID-19, as well as the ongoing is the author of Pain, Pride, and Politics: Sri Lankan impact on social cohesion in the country. -

“Everyone Has Been Silenced”; Police

EVERYONE HAS BEEN SILENCED Police Excesses Against Anti-CAA Protesters In Uttar Pradesh, And The Post-violence Reprisal Citizens Against Hate Citizens against Hate (CAH) is a Delhi-based collective of individuals and groups committed to a democratic, secular and caring India. It is an open collective, with members drawn from a wide range of backgrounds who are concerned about the growing hold of exclusionary tendencies in society, and the weakening of rule of law and justice institutions. CAH was formed in 2017, in response to the rising trend of hate mobilisation and crimes, specifically the surge in cases of lynching and vigilante violence, to document violations, provide victim support and engage with institutions for improved justice and policy reforms. From 2018, CAH has also been working with those affected by NRC process in Assam, documenting exclusions, building local networks, and providing practical help to victims in making claims to rights. Throughout, we have also worked on other forms of violations – hate speech, sexual violence and state violence, among others in Uttar Pradesh, Haryana, Rajasthan, Bihar and beyond. Our approach to addressing the justice challenge facing particularly vulnerable communities is through research, outreach and advocacy; and to provide practical help to survivors in their struggles, also nurturing them to become agents of change. This citizens’ report on police excesses against anti-CAA protesters in Uttar Pradesh is the joint effort of a team of CAH made up of human rights experts, defenders and lawyers. Members of the research, writing and advocacy team included (in alphabetical order) Abhimanyu Suresh, Adeela Firdous, Aiman Khan, Anshu Kapoor, Devika Prasad, Fawaz Shaheen, Ghazala Jamil, Mohammad Ghufran, Guneet Ahuja, Mangla Verma, Misbah Reshi, Nidhi Suresh, Parijata Banerjee, Rehan Khan, Sajjad Hassan, Salim Ansari, Sharib Ali, Sneha Chandna, Talha Rahman and Vipul Kumar. -

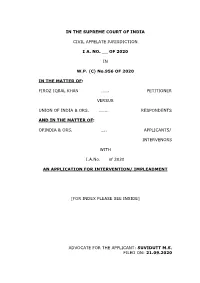

Impleadment Application

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CIVIL APPELATE JURISDICTION I A. NO. __ OF 2020 IN W.P. (C) No.956 OF 2020 IN THE MATTER OF: FIROZ IQBAL KHAN ……. PETITIONER VERSUS UNION OF INDIA & ORS. …….. RESPONDENTS AND IN THE MATTER OF: OPINDIA & ORS. ….. APPLICANTS/ INTERVENORS WITH I.A.No. of 2020 AN APPLICATION FOR INTERVENTION/ IMPLEADMENT [FOR INDEX PLEASE SEE INSIDE] ADVOCATE FOR THE APPLICANT: SUVIDUTT M.S. FILED ON: 21.09.2020 INDEX S.NO PARTICULARS PAGES 1. Application for Intervention/ 1 — 21 Impleadment with Affidavit 2. Application for Exemption from filing 22 – 24 Notarized Affidavit with Affidavit 3. ANNEXURE – A 1 25 – 26 A true copy of the order of this Hon’ble Court in W.P. (C) No.956/ 2020 dated 18.09.2020 4. ANNEXURE – A 2 27 – 76 A true copy the Report titled “A Study on Contemporary Standards in Religious Reporting by Mass Media” 1 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CIVIL ORIGINAL JURISDICTION I.A. No. OF 2020 IN WRIT PETITION (CIVIL) No. 956 OF 2020 IN THE MATTER OF: FIROZ IQBAL KHAN ……. PETITIONER VERSUS UNION OF INDIA & ORS. …….. RESPONDENTS AND IN THE MATTER OF: 1. OPINDIA THROUGH ITS AUTHORISED SIGNATORY, C/O AADHYAASI MEDIA & CONTENT SERVICES PVT LTD, DA 16, SFS FLATS, SHALIMAR BAGH, NEW DELHI – 110088 DELHI ….. APPLICANT NO.1 2. INDIC COLLECTIVE TRUST, THROUGH ITS AUTHORISED SIGNATORY, 2 5E, BHARAT GANGA APARTMENTS, MAHALAKSHMI NAGAR, 4TH CROSS STREET, ADAMBAKKAM, CHENNAI – 600 088 TAMIL NADU ….. APPLICANT NO.2 3. UPWORD FOUNDATION, THROUGH ITS AUTHORISED SIGNATORY, L-97/98, GROUND FLOOR, LAJPAT NAGAR-II, NEW DELHI- 110024 DELHI ….