Ekrany 56 Ang Cc21.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EXTENSIONS of REMARKS February 22, 1973

5200 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS February 22, 1973 ORDER FOR RECOGNITION OF SEN be cousin, the junior Senator from West DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE ATOR ROBERT C. BYRD ON MON Virginia (Mr. ROBERT c. BYRD)' for a James N. Gabriel, of Massachusetts, to be DAY period of not to exceed 15 minutes; to be U.S. attorney for the district of Massachu Mr. ROBERT c. BYRD. I ask unani followed by a period for the transaction setts for the term of 4 years, vice Joseph L. mous consent that following the remarks of routine morning business of not to Tauro. exceed 30 minutes, with statements James F. Companion, of West Virginia, to of the distinguished senior Senator from be U.S. attorney for the northern district of Virginia (Mr. HARRY F. BYRD, JR.) on therein limited to 3 minutes, at the con West Virginia for the term of 4 years, vice Monday, his would-be cousin, Mr. RoB clusion of which the Senate will proceed Paul C. Camilletti, resigning. ERT C. BYRD, the junior Senator from to the consideration of House Joint Reso lution 345, the continuing resolution. IN THE MARINE CORPS West Virginia, the neighboring State just The following-named officers of the Marine over the mountains, be recognized for not I would anticipate that there would Corps for temporary appointment to the to exceed 15 minutes. likely be a rollcall vote--or rollcall grade of major general: The PRESIDING OFFICER. Without votes--in connection with that resolu Kenneth J. HoughtonJames R. Jones objection, it is so ordered. tion, but as to whether or not the Senate Frank C. -

FILM 308.80: Russian Cinema and Culture Clint B

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Syllabi Course Syllabi Fall 9-1-2018 FILM 308.80: Russian Cinema and Culture Clint B. Walker University of Montana, Missoula Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/syllabi Recommended Citation Walker, Clint B., "FILM 308.80: Russian Cinema and Culture" (2018). Syllabi. 8242. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/syllabi/8242 This Syllabus is brought to you for free and open access by the Course Syllabi at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Syllabi by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Prof. Clint Walker Russian Cinema and Culture LA 330, x2501 FILM 308 [email protected] Mon and Wed, 2-4:20pm, NAC 009 Office Hours: M 10-11am, 12-1pm and by appointment in LA 330 Russian Cinema and Culture LEARNING OUTCOMES and OBJECTIVES: This course provides students with a thematic-centered introduction to Russian and Soviet Cinema. Rather than organizing the material chronologically, I have opted to arrange the films in thematic clusters. Thematic units include: Responses to Stalinism in Russian Cinema; Identity and Otherness in Russian Cinema; Women, Gender, and Sexuality in Russian Cinema; Exploring Genres in Russian Cinema. Within each thematic unit, the films are arranged chronologically to allow us to trace the progression of the theme and its exploration and depiction via the cinematic medium in various cultural epochs. My main learning objective in this class is thus twofold: to acquaint you with several thematic clusters that play a major role in the development of Russian cinema; to provide you with enough cultural background to enable you to appreciate more fully how the exploration of these themes evolved and changed through various historical and cultural periods. -

Press-Kit Presents a Film by Konstantin Lopushansky THROUGH THE

Press-kit presents A film by Konstantin Lopushansky THROUGH THE BLACK GLASS The drama titled Through the Black Glass is a modern interpretation of such famous classical plots as Cinderella and Scarlet Sails, with a touch of Chaplin`s City Lights. The main heroine is an 18-year-old blind girl from a provincial orphanage, who unexpectedly gets a chance of a lifetime. A wealthy man offers to pay for an expensive eye surgery on the condition that she agrees to marry him before the operation, without a single glance at the groom. Alas, fate hands out happy endings sparingly, and the vision, miraculously regained by the heroine, gives her an unpleasant insight into stark realities of life. The film directed by Konstantin Lopushansly, who also wrote the original script, is not just a new rendition of the classical plot; it is a deep glance at the ambiguous relationship between men and women in the present-day Russia. The author makes an emphasis on dynamics of editing, music, photography, and, obviously, the choice of actors. The director says, “You can analyze the film in view of several genres: tragic melodrama, a modern rendition of the classical Cinderella plot, and a religious drama loosely based on the conceptual conflict in Dostoevsky`s Gentle Creature. The story is centered at the tragic collision of two world outlooks: the religious belief and the atheistic view, set against the newest Russian history. The latter interpretation is the closest to me, and is in tune with my views as a film director. Yet, this still leaves space for detailed elaboration into the other two variants, melodrama being the priority. -

The Uses of Animation 1

The Uses of Animation 1 1 The Uses of Animation ANIMATION Animation is the process of making the illusion of motion and change by means of the rapid display of a sequence of static images that minimally differ from each other. The illusion—as in motion pictures in general—is thought to rely on the phi phenomenon. Animators are artists who specialize in the creation of animation. Animation can be recorded with either analogue media, a flip book, motion picture film, video tape,digital media, including formats with animated GIF, Flash animation and digital video. To display animation, a digital camera, computer, or projector are used along with new technologies that are produced. Animation creation methods include the traditional animation creation method and those involving stop motion animation of two and three-dimensional objects, paper cutouts, puppets and clay figures. Images are displayed in a rapid succession, usually 24, 25, 30, or 60 frames per second. THE MOST COMMON USES OF ANIMATION Cartoons The most common use of animation, and perhaps the origin of it, is cartoons. Cartoons appear all the time on television and the cinema and can be used for entertainment, advertising, 2 Aspects of Animation: Steps to Learn Animated Cartoons presentations and many more applications that are only limited by the imagination of the designer. The most important factor about making cartoons on a computer is reusability and flexibility. The system that will actually do the animation needs to be such that all the actions that are going to be performed can be repeated easily, without much fuss from the side of the animator. -

CALIFORNIA's NORTH COAST: a Literary Watershed: Charting the Publications of the Region's Small Presses and Regional Authors

CALIFORNIA'S NORTH COAST: A Literary Watershed: Charting the Publications of the Region's Small Presses and Regional Authors. A Geographically Arranged Bibliography focused on the Regional Small Presses and Local Authors of the North Coast of California. First Edition, 2010. John Sherlock Rare Books and Special Collections Librarian University of California, Davis. 1 Table of Contents I. NORTH COAST PRESSES. pp. 3 - 90 DEL NORTE COUNTY. CITIES: Crescent City. HUMBOLDT COUNTY. CITIES: Arcata, Bayside, Blue Lake, Carlotta, Cutten, Eureka, Fortuna, Garberville Hoopa, Hydesville, Korbel, McKinleyville, Miranda, Myers Flat., Orick, Petrolia, Redway, Trinidad, Whitethorn. TRINITY COUNTY CITIES: Junction City, Weaverville LAKE COUNTY CITIES: Clearlake, Clearlake Park, Cobb, Kelseyville, Lakeport, Lower Lake, Middleton, Upper Lake, Wilbur Springs MENDOCINO COUNTY CITIES: Albion, Boonville, Calpella, Caspar, Comptche, Covelo, Elk, Fort Bragg, Gualala, Little River, Mendocino, Navarro, Philo, Point Arena, Talmage, Ukiah, Westport, Willits SONOMA COUNTY. CITIES: Bodega Bay, Boyes Hot Springs, Cazadero, Cloverdale, Cotati, Forestville Geyserville, Glen Ellen, Graton, Guerneville, Healdsburg, Kenwood, Korbel, Monte Rio, Penngrove, Petaluma, Rohnert Part, Santa Rosa, Sebastopol, Sonoma Vineburg NAPA COUNTY CITIES: Angwin, Calistoga, Deer Park, Rutherford, St. Helena, Yountville MARIN COUNTY. CITIES: Belvedere, Bolinas, Corte Madera, Fairfax, Greenbrae, Inverness, Kentfield, Larkspur, Marin City, Mill Valley, Novato, Point Reyes, Point Reyes Station, Ross, San Anselmo, San Geronimo, San Quentin, San Rafael, Sausalito, Stinson Beach, Tiburon, Tomales, Woodacre II. NORTH COAST AUTHORS. pp. 91 - 120 -- Alphabetically Arranged 2 I. NORTH COAST PRESSES DEL NORTE COUNTY. CRESCENT CITY. ARTS-IN-CORRECTIONS PROGRAM (Crescent City). The Brief Pelican: Anthology of Prison Writing, 1993. 1992 Pelikanesis: Creative Writing Anthology, 1994. 1994 Virtual Pelican: anthology of writing by inmates from Pelican Bay State Prison. -

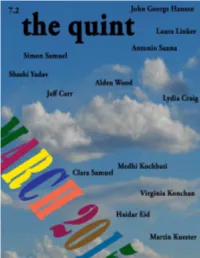

The Quint V7.2

the quint : an interdisciplinary quarterly from the north 1 contents the quint volume seven issue two EDITORIAL an interdisciplinary quarterly from "Tick -Tock" by Lydia Craig........................................................................................................6 Ditch #1 by Anne Jevne.............................................................................................................8 the north (Post)modernism and Globalization byHaidar Eid....................................................................9 advisory board Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds by Virginia Konchan.............................................................23 Dr. Keith Batterbe ISSN 1920–1028 Ditch #2 by Anne Jevne............................................................................................................24 University of Turku e Autonomous Mind of Waskechak by John George Hansen.................................................25 Dr. Lynn Ecchevarria Raised by His Grandmother Legend: Child of Caribou by Simon Samuel................................44 Yukon College Ditch #3 by Anne Jevne...........................................................................................................50 Dr. Susan Gold the quint welcomes submissions. See our guidelines Milton in Canada: Ideal, Ghost or Inspiration? by Martin Kuester.........................................51 University of Windsor or contact us at: Die Walküre by Virginia Konchan..........................................................................................75 -

Czechdocs2017-Web.Pdf

Dear friends of documentary fi lms, This catalogue and its online version at www.czechdocs.net contain the profi les of the most recent and upcoming documentaries in Czech production or co-production. Almost 20 of them have already had their premiere, the rest of them are in various stages of production and will be released by the end of 2018. In 2016, Czech documentaries were doing really well within the local distribution, 23 of them premiered in cinemas, and also abroad, as many of them were successfully presented and awarded at prestigious international fi lm festivals. Among the Czech docs screened abroad there were for example two fi lms by Helena Třeštíková: Mallory (at Hot Docs in Canada and Hong Kong IFF) and Doomed Beauty (Busan IFF). Other successful Czech representatives on the international scene were the co-production fi lm Under the Sun by Vitaly Mansky or 5 October by Martin Kollár (screened in Rotterdam). The Normal Autistic Film by Miroslav Janek, the Czech winner from Jihlava IDFF 2016, had its international premiere at DOK Leipzig, managed to get a sales agent and sell the rights to the U.S. distributor. Both Czech Film Center and Institute of Documentary Film continually make efforts to make Czech documentaries visible on the international scene. Czech documentaries are being presented at East Doc Platform in Prague within the Czech Docs… Coming Soon event, or at key international markets abroad – at IDFA, in Cannes, at Berlinale, in Clermont-Ferrand, or at goEAST within the delegations led by IDF and CFC representatives. Moreover, Czech Film Center becomes part of State Cinematography Fund, the main institution supporting the development and production of Czech fi lms in general. -

Film Financing

2017 An Outsider’s Glimpse into Filmmaking AN EXPLORATION ON RECENT OREGON FILM & TV PROJECTS BY THEO FRIEDMAN ! ! Page | !1 Contents Tracktown (2016) .......................................................................................................................6 The Benefits of Gusbandry (2016- ) .........................................................................................8 Portlandia (2011- ) .....................................................................................................................9 The Haunting of Sunshine Girl (2010- ) ...................................................................................10 Green Room (2015) & I Don’t Feel at Home in This World Anymore (2017) ...........................11 Network & Experience ............................................................................................................12 Financing .................................................................................................................................12 Filming ....................................................................................................................................13 Distribution ...............................................................................................................................13 In Conclusion ...........................................................................................................................13 Financing Terms .....................................................................................................................15 -

Copyright by Leah Michelle Ross 2012

Copyright by Leah Michelle Ross 2012 The Dissertation Committee for Leah Michelle Ross Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: A Rhetoric of Instrumentality: Documentary Film in the Landscape of Public Memory Committee: Katherine Arens, Supervisor Barry Brummett, Co-Supervisor Richard Cherwitz Dana Cloud Andrew Garrison A Rhetoric of Instrumentality: Documentary Film in the Landscape of Public Memory by Leah Michelle Ross, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December, 2012 Dedication For Chaim Silberstrom, who taught me to choose life. Acknowledgements This dissertation was conceived with insurmountable help from Dr. Katherine Arens, who has been my champion in both my academic work as well as in my personal growth and development for the last ten years. This kind of support and mentorship is rare and I can only hope to embody the same generosity when I am in the position to do so. I am forever indebted. Also to William Russell Hart, who taught me about strength in the process of recovery. I would also like to thank my dissertation committee members: Dr Barry Brummett for his patience through the years and maintaining a discipline of cool; Dr Dana Cloud for her inspiring and invaluable and tireless work on social justice issues, as well as her invaluable academic support in the early years of my graduate studies; Dr. Rick Cherwitz whose mentorship program provides practical skills and support to otherwise marginalized students is an invaluable contribution to the life of our university and world as a whole; Andrew Garrison for teaching me the craft I continue to practice and continuing to support me when I reach out with questions of my professional and creative goals; an inspiration in his ability to juggle filmmaking, teaching, and family and continued dedication to community based filmmaking programs. -

Download Download

Polish Feature Film after 1989 By Tadeusz Miczka Spring 2008 Issue of KINEMA CINEMA IN THE LABYRINTH OF FREEDOM: POLISH FEATURE FILM AFTER 1989 “Freedom does not exist. We should aim towards it but the hope that we will be free is ridiculous.” Krzysztof Kieślowski1 This essay is the continuation of my previous deliberations on the evolution of the Polish feature film during socialist realism, which summarized its output and pondered its future after the victory of the Solidarity movement. In the paper “Cinema Under Political Pressure…” (1993), I wrote inter alia: “Those serving the Tenth Muse did not notice that martial law was over; they failed to record on film the takeover of the government by the political opposition in Poland. […] In the new political situation, the society has been trying to create a true democratic order; most of the filmmakers’ strategies appeared to be useless. Incipit vita nova! Will the filmmakers know how to use the freedom of speech now? It is still too early toanswer this question clearly, but undoubtedly there are several dangers which they face.”2 Since then, a dozen years have passed and over four hundred new feature films have appeared on Polish cinema screens, it isnow possible to write a sequel to these reflections. First of all it should be noted that a main feature of Polish cinema has always been its reluctance towards genre purity and display of the filmmaker’s individuality. That is what I addressed in my earlier article by pointing out the “authorial strategies.” It is still possible to do it right now – by treating the authorial strategy as a research construct to be understood quite widely: both as the “sphere of the director” or the subjective choice of “authorial role,”3 a kind of social strategy or social contract.4 Closest to my approach is Tadeusz Lubelski who claims: “[…] The practical application of authorial strategies must be related to the range of social roles functioning in the culture of a given country and time. -

Coronavirus and the European Film Industry

BRIEFING Coronavirus and the European film industry SUMMARY With the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, which has caused the shutdown of some 70 000 cinemas in China, nearly 2 500 in the US and over 9 000 in the EU, the joy sparked by the success of the film industry in 2019 has quickly given way to anxiety. Shootings, premieres, spring festivals and entertainment events have faced near-total cancellation or postponement due to the pandemic, thus inflicting an estimated loss of US$5 billion on the global box office; this amount could skyrocket to between US$15 billion and US$17 billion, if cinemas do not reopen by the end of May 2020. The EU film sector is essentially made up of small companies employing creative and technical freelancers, which makes it particularly vulnerable to the pandemic. The domino effect of the lockdown has triggered the immediate freeze of hundreds of projects in the shooting phase, disrupted cash flows and pushed production companies to the brink of bankruptcy. To limit and/or mitigate the economic damage caused by coronavirus, governments and national film and audiovisual funds across the EU have been quick in setting up both general blanket measures (such as solidarity funds and short-term unemployment schemes) and/or specific industry-related funds and grants (helping arthouse cinema and providing financial relief to producers and distributors). For its part, the EU has acted promptly to limit the spread of the virus and help EU countries to withstand its social and economic impact. In addition to the Coronavirus Response Investment Initiative (CRII) and the CRII+, both approved by the European Parliament and the Council in record time, the Commission has set up a Temporary Framework allowing EU countries to derogate from State aid rules, and proposed a European instrument for temporary support (SURE) to help protect jobs and workers affected by the coronavirus pandemic. -

Ballads and Poems Relating to the Burgoyne Campaign. Annotated

: : : to vieit Europe, I desire to state that his great accjuaintancc witti military matters, his long and faithful research into the military histories of modern nations, his correct comprehension of our own late war, and his intimacy with man.v of our leading Generals and Statesmen durinjr the period of its con- tinuance, with his tried and devoted loyalty and patriotism, recommend him as an eminently suitable person to visit foreign countries, to impart as weU as receive proper views upon all such subjects as are connected with his position as a military writer. Such high qualifications, apart from his being a gentleman of family, of fortune, and of refined cultivation, are entitled to the most favorable consideration from all thosH who esteem and admire them. With great respect, A. PLEA8ANTON, Bvt. Major- Gen'l, U.S.A. ExEcunvK Manbioh, I; Wati., D. C, July 13, 1869. f I heartily concur with Gen'l Pleasanton in his high appreciation of the services rendered by Gen'l de Peysteb, upon whom the State of New York has conferred the rank of Brevet Major-General. I commend him to the favorable consideration of those whom he may meet in his present visit to Europe. U. S. GRANT. ExEcunri Mansion, 1 W<ukingtm, D. a, July I3th, 1869. Dear Sir • ) I take pleasure in forwarding to you the enclosed endorsement of the President. Yours Very Truly, Gen. J. Watts db Pktsteb. HORACE PORTER.* •Major of Ordnance, V. 8. A. ; Brtvtt Brigadier-General V. S. A.; A.-de-C. to tke General-in-Chief ; and Private Secretary to the Pretident of the U.S.