Education and Countering Violent Extremism: a Case Study of Schools in Pakistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JOURNAL of PROFESSIONAL RESEARCH in SOCIAL SCIENCES Prof

JPRSS, Vol. 1, No. 1, July 2014 JOURNAL OF PROFESSIONAL RESEARCH IN SOCIAL SCIENCES Prof. Dr. Naudir Bakht Editor In-Chief Journal of Professional Research in Social Sciences provides a forum for discussion on issues and problems primarily relating to Pakistan. We welcome contributions by researchers, administrators, policy makers and all others interested in promoting better understanding of Pakistan affairs. Published in Summer and Winter every Year, articles appearing in the journal are recognized by Higher Education Commission for promotion and appointments and are indexed and abstracted in international Bibliography of Social Sciences, London and International Politics Science Abstracts, Paris. The journal is also available online at http://www.mul.edu.pk/crd Disclaimer Views expressed in the Journal of Professional Research in Social Sciences do not reflect the views of the Centre or the Editors. Responsibility for the accuracy of facts and for the opinions expressed rests solely with the authors. Subscription Rates Pakistan Annual Rs. 400.00 Single Copy Rs. 250.00 Foreign Annual Rs. U.S. $ 50.00 Single Copy Rs. U.S. $ 30.00 Correspondence All correspondence should be directed to the Director/Editor-in-Chief, Journal of Professional Research in Social Sciences, Minhaj University, Hamdard Chowk, Township, Lahore - Pakistan. MINHAJ UNIVERSITY LAHORE 2014 © Copyright by All rights reserved. The material printed in this journal may not be reproduced in any form without prior permission of the Director. Journal of Professional Research in Social Sciences JPRSS, Vol. 1, No. 1, July 2014 JOURNAL OF PROFESSIONAL RESEARCH IN SOCIAL SCIENCES Vol. 1, No.1 Summer 2014 Centre for Research and Development Faculty of Social Sciences Contact: +92-42-35145621-6, Ext. -

JPRSS, Vol. 03, No. 01, Summer 2016 Journal of Professional Research

JPRSS, Vol. 03, No. 01, Summer 2016 JOURNAL OF PROFESSIONAL RESEARCH IN SOCIAL SCIENCES Prof. Dr. Naudir Bakht Editor In-Chief It is a matter of great honor and pleasure for me and my team that by the fabulous and continuous cooperation of our distinguished National/International Contributors/ Delegates, we are able to present our Research Journal, “Journal of Professional Research in Social Sciences, Vol. 03, No. 01, Summer 2016 . The Centre has made every effort to improve the quality and standard of the paper, printing and of the matter. I feel honored to acknowledge your generous appreciation, input and response for the improvement of the Journal. I offer my special thanks to: 1. Prof. Dr. Neelambar Hatti, Professor Emeritus, Department of Economic History, Lund University, Sweden 2. Ms. Bushra Almas Jaswal Chief Librarian & Associate Professor Ewing Memorial Library Forman Christian College 3. Dr. Shahid Siddiqui Vice Chancellor Allama Iqbal Open University Islamabad 4. Prof. Dr. Javed Haider Syed Chairman Department of History & Pakistan Studies University of Gujrat Journal of Professional Research in Social Sciences JPRSS, Vol. 03, No. 01, Summer 2016 5. Engr. Prof. Dr. Sarfraz Hussain, TI(M), SI(M) Vice Chancellor DHA Sufa University DHA, Karachi 6. Prof. Dr. Najeed Haider Registrar Ghazi University, D.G Khan 7. Muhammad Yousaf Dy. Registrar City University Peshawar 8. Dr. Bashir Goraya Vice Chancellor Al-Khair University (AJK) 9. Safia Imtiaz Librarian Commecs Institute of Business and Emerging Science 10. Prof. Dr. Dost Ali Khowaja Academic Coordinator, FOE Dawood University of Engineering and Technology 11. Prof. Dr. M. Shamsuddin Honorary Advisor to VC University of Karachi 12. -

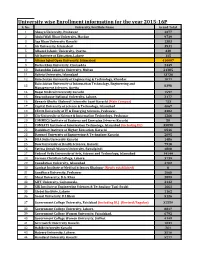

University Wise Enrollment Information for the Year 2015-16P S

University wise Enrollment information for the year 2015-16P S. No. University/Institute Name Grand Total 1 Abasyn University, Peshawar 4377 2 Abdul Wali Khan University, Mardan 9739 3 Aga Khan University Karachi 1383 4 Air University, Islamabad 3531 5 Alhamd Islamic University, Quetta. 338 6 Ali Institute of Education, Lahore 115 8 Allama Iqbal Open University, Islamabad 416607 9 Bacha Khan University, Charsadda 2449 10 Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan 21385 11 Bahria University, Islamabad 13736 12 Balochistan University of Engineering & Technology, Khuzdar 1071 Balochistan University of Information Technology, Engineering and 13 8398 Management Sciences, Quetta 14 Baqai Medical University Karachi 1597 15 Beaconhouse National University, Lahore. 2177 16 Benazir Bhutto Shaheed University Lyari Karachi (Main Campus) 753 17 Capital University of Science & Technology, Islamabad 4067 18 CECOS University of IT & Emerging Sciences, Peshawar. 3382 19 City University of Science & Information Technology, Peshawar 1266 20 COMMECS Institute of Business and Emerging Sciences Karachi 50 21 COMSATS Institute of Information Technology, Islamabad (including DL) 35890 22 Dadabhoy Institute of Higher Education, Karachi 6546 23 Dawood University of Engineering & Technology Karachi 2095 24 DHA Suffa University Karachi 1486 25 Dow University of Health Sciences, Karachi 7918 26 Fatima Jinnah Women University, Rawalpindi 4808 27 Federal Urdu University of Arts, Science and Technology, Islamabad 14144 28 Forman Christian College, Lahore. 3739 29 Foundation University, Islamabad 4702 30 Gambat Institute of Medical Sciences Khairpur (Newly established) 0 31 Gandhara University, Peshawar 1068 32 Ghazi University, D.G. Khan 2899 33 GIFT University, Gujranwala. 2132 34 GIK Institute of Engineering Sciences & Technology Topi-Swabi 1661 35 Global Institute, Lahore 1162 36 Gomal University, D.I.Khan 5126 37 Government College University, Faislabad (including DL) (Revised/Regular) 32559 38 Government College University, Lahore. -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Prof. Kanwal Ameen (PhD) Vice Chancellor, University of Home Economics Lahore [email protected] -------------------------------------------------- Former: University of the Punjab (PU), Lahore-Pakistan. Director, Directorate of External Linkages (July 2018- May 2019), Chairperson, Department of Information Management (May 2009- May 2018) Chair, Doctoral Program Coordination Committee, PU (2013-2017) Chief Editor, Pakistan Journal of Information Management & Libraries (2009-2018) Founding Chair, South Asia Chapter, ASIS&T (Association for Information Science & Technology, USA; 2018) Professor/Scholar in Residence, University of Tsukuba, Japan (2013) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kanwal_Ameen https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=ZhuLbeYAAAAJ&hl=en https://pu-pk1.academia.edu/ProfDrKanwalAmeen; https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Kanwal_Ameen https://pk.linkedin.com/in/kanwal-ameen-ph-d-761b9b15 Awards and Scholarships National ● Women Excellence Award 2020. UN Women Pakistan, PPIF, Govt. of Punjab ● Indigenous Post-Doctoral Supervision Award (2018-2019), Punjab Higher Education Commission (PHEC) ● Best Paper Awards in 2015/16 and 2017, Pakistan Higher Education Commission (HEC) ● Best Teacher Award 2010, HEC ● Best Teacher Awards, University of the Punjab ● Lifetime Academic Achievements Award 2009, Pakistan Library Association, ● HEC, PHEC, PU Travel grants to present papers at international conferences. International ● James Cretsos Leadership Award, 2019, Association of Information Science &Technology, (ASIS&T, USA), ● Best Paper Award, 2017, ASIS&T(USA) SIG III ● Emerald Award of Excellence for Outstanding Paper, 2009 ● A-LIEP Best Paper Award in 2006 ● FULBRIGHT AWARDS ○ Pre-Doc (2000-2001) University of Texas at Austin, USA ○ Post-Doc (2009-2010) University of Missouri, Columbia, USA ○ Fulbright Occasional Lecture Fund, 2010, North Carolina, USA ● Asian Library Leaders “Award for Professional Excellence – 2013, SRFLIS, Delhi, India. -

Dr Hussain Mohi Ud Din Qadri

MASTERING THE DATA REVOLUTION - IN THE SHADOW OF COVID-19 THE ART OF MAKING SMART SHARI’A DECISIONS IN ISLAMIC BANKING AMIDST COVID-19 AN EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW with DR HUSSAIN MOHIUDDIN QADRI PRESIDENT, MINHAJ UL QURAN INTERNATIONAL & DEPUTY CHAIRMAN, BOARD OF GOVERNORS MINHAJ UNIVERSITY LAHORE ISFIRE ISFIRE COVER STORY COVER STORY Dr Hussain Mohi-ud-Din Qadri, let us led to my interest in Islamic banking the fleet of financial products offered start with yourself by asking how you and finance, inspired and motivated by Islamic financial institutions THE ISLAMIC ECONOMIC got interested in Islamic finance on a me to study further, contemplate throughout the world? SYSTEM, THOUGH NOT personal level. and become a representative of the Product development is one of As you know that Minhaj-ul-Quran Islamic economic system. After joining the paramount requisites for the CURRENTLY ON THE International has been founded by the Minhaj University, the first two sustainability of the Islamic banking Shaykh-ul-Islam Prof. Dr. Muhammad new departments I established was and finance industry at a global level. SCENE WITH ITS ENTIRE Tahir-ul-Qadri in 1980 and he based the School of Islamic Economics, Without bringing innovative and it on knowledge and education. The Banking and Finance, and the customer-tailored products, Islamic BEAUTY AND EXCELLENCE, objectives behind this step were to International Center for Research banking and finance industry would revive the values, factors, elements and in Islamic Economics (ICRIE). These become less attractive for the existing CONTAINS THE programmes that had been granted platforms have been used to organise customers and not be able to attain to the Ummah by the Holy Prophet Pakistan’s biggest conference of Islamic new ones. -

The South Asian Journal of Religion and Philosophy

SAJRP Vol. 1 No. 2 (July/August 2020) THE SOUTH ASIAN JOURNAL OF RELIGION AND PHILOSOPHY Patron-in-Chief: Dr. Hussain Mohi-Ud-Din Qadri Deputy Chairman, Board of Governors Minhaj University Lahore Patron: Dr. Sajid Mahmood Shahzad Vice-Chancellor Minhaj University Lahore Editor-in-Chief: Dr. Herman Roborgh Head, School of Religion & Philosophy Minhaj University Lahore Co-Editor: Dr. Shanthikumar Hettiarachchi Professor, School of Religion & Philosophy Minhaj University Lahore Book Review Editor Dr. Kristin Beise Kiblinger Winthrop University South Carolina, USA National Editorial Board: Dr. Alqama Khwaja Minhaj University Lahore Dr. Nabila Ishaq, Shari’ah College, Lahore Dr. Hafiz Abdul Ghani, Foreman Christian College University, Lahore Dr. Akram Rana, Shari’ah College, Lahore Dr. Farzand Masih, Foreman Christian College University, Lahore Dr. Mukhtar Ahmad Azmi, Minhaj University Lahore Fr. Carlos Juan, Loyola Research Centre, Lahore Manager: Dr. Khurram Shahzad SAJRP Vol. 1 No. 2 (July/August 2020) International Editorial Board: Dr. Ismail Albayrak, Australian Catholic University, Melbourne, Australia Dr. Paul Hedges, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore Dr. Victor Edwin, Vidyajyoti College of Theology, Delhi, India Dr. Alan Race, Chair and Editor in Chief of Interreligious Insight, United Kingdom Dr. John Dupuche, University of Divinity, Melbourne, Australia Dr. Miroljub Jevtic, Centre for the Study of Religion and Religious Tolerance, Belgrade, Serbia Dr. Peter Riddell, School of Asian Studies, University of London, United Kingdom Dr. Abdullah Saeed, University of Melbourne, Australia Dr. Charles M. Ramsey, Baylor University, United States of America Text Designing & Arqam Bilal Formatting: Cover Design: Tahir Mehmood Production: Minhaj ul Quran Publications Copyright © School of Religion and Philosophy & Centre for Research and Development (CRD) all rights reserved. -

Core Competencies Required by University Librarians for the Adoption of Information Technology Tools: an Empirical Study

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal) Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln 2021 Core Competencies Required by University Librarians for the Adoption of Information Technology Tools: An Empirical Study Khurram Shahzad GC University, Lahore, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Shahzad, Khurram, "Core Competencies Required by University Librarians for the Adoption of Information Technology Tools: An Empirical Study" (2021). Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal). 6061. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/6061 Core Competencies Required by University Librarians for the Adoption of Information Technology Tools: An Empirical Study By: Khurram Shahzad Government College University Lahore, Pakistan (www.gcu.edu.pk) E-mails: [email protected]; [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-7562-9933 Abstract: Purpose: This study explores core competencies that are needed by library professionals for the implementation of Information Technology (IT) Tools in the university library of Lahore, Pakistan. Methodology/Approach: A quantitative approach followed by survey research design was opted to complete the study on the competencies which are needed by library professionals for the implementation of Information Technology (IT) in the university library of Lahore, Pakistan. A total of 120 questionnaires were distributed among university librarians of Lahore. All questionnaires were sent through emails. 91 duly filled questionnaires were received by the researchers from the respondents. The response rate was 75.83%. Research limitation (s): This study is limited to the university library of Lahore, Pakistan. Key finding (s): Results of the study show that Librarians need IT skills for applying the latest technologies in their libraries. -

5Th Ranking of Pakistani Higher Education Institutions (Heis) 2015

HIG HER EDUC ATION COMMISSION 5th Ranking of Pakistani Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) 2015 Announced: 23.2.2016 Objective To create culture of competition among the Higher Education Institutions (HEIs). Encourage HEIs to compete at international level, improve quality/standards of education and use as tool for HEIs self-assessment of their performance for improvement. Introduction Ranking provide complete picture to stakeholders like researchers, students, business community, parents, industry etc. to compare institutions according to different parameters of their need, such as Quality & Research etc. For the development and progress of any country, quality of higher education is the key factor. HEIs are considered to be the originators of change and progress of the nations. In order to strengthen the quality of higher education in Pakistan, Higher Education Commission (HEC) has taken various initiatives to bring the HEIs of Pakistan at par with international standards. Ranking is one of the measures to scale the success of efforts of the HEIs to achieve the international competitiveness in education, research and innovation. Rankings is a debatable subject all over the world, In spite of the difficulties associated in ranking. This is the 5th ranking of Pakistani Universities being announced by Higher Education Commission of Pakistan. Last four rankings for the year were announced in 2006, 2012, 2013 and 2015. Methodology The methodologies for ranking got improved over the period of time in the light of feedback received from HEIs and making HEC's ranking more compatible with global rankings. There is no change in the ranking criteria for the current year ( 2015 ) and criteria is the same which was used for ranking 2014. -

CV of Dr. Saira Hanif Soroya

Department of Information Management University of the Punjab, Lahore +923138109726 Email: [email protected] Google Scholar Profile: Dr. Saira Hanif Soroya ResearchGate Profile: Saira Soroya DR. SAIRA HANIF SOROYA EDUCATION PH. D. IN LIBRARY AND INFORMATION SCIENCE (DEPARTMENT OF INFORMATION MANAGEMENT, UNIVERSITY OF THE PUNJAB, LAHORE) 2012-2016 M. PHIL. IN LIBRARY AND INFORMATION SCIENCE (DEPARTMENT OF INFORMATION MANAGEMENT, UNIVERSITY OF THE PUNJAB, LAHORE) 2009-2011 MASTERS IN LIBRARY AND INFORMATION SCIENCE (DEPARTMENT OF INFORMATION MANAGEMENT, UNIVERSITY OF THE PUNJAB, LAHORE) 2002-2004 EXPERIENCE • ASSISTANT PROFESSOR 05 December 2016- to date • LIBRARIAN, IAGS, UNIVERSITY OF THE PUNJAB, LAHORE. November 2013 – To- December 2016 • LECTURER, DLIS, UNIVERSITY OF SARGODHA, SARGODHA January 2013 – To - November 2013 • LIBRARIAN, IAGS, UNIVERSITY OF THE PUNJAB, LAHORE. July 2008 – To January 2013 COURSES TAUGHT • Advanced Research Methods (M.Phil., Clinical Psychology) • Business Research Methods” to the class of MBA. • Collection Development (Masters, Library & Information Science) • Data Analysis (M.Phil., Mass Communication, and Education) • Digital Libraries (Masters, Library & Information Science) • Human Information Behavior (Masters, Library & Information Science) • Information Literacy (Masters, Library & Information Science) • Information Retrieval Systems (Masters, Library & Information Science) • Information Science) • Information Technology (Masters, Library & Information Science) • Introduction to Computer (BS, Economics) • Introduction to Research (BS, Library & Information Science) • Marketing of Information Products & Services (Masters & M.Phil., Library & • Organization of Information (BS, Library & Information Science) • Research Seminar (M.Phil, Information Management) • Theoretical Foundations of Library and Information Science (MPhil) RESAERCH Research Supervised CONTRIBUTIONS Ph. D. Theses 1. Waqar Ahmed Awan. (Submitted). Information Encountering, Keeping and Sharing Behavior of Researchers in Online Environment. 2. Tauseef Hussain. -

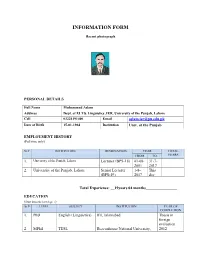

CV of Mr. Muhammad Aslam

INFORMATION FORM Recent photograph PERSONAL DETAILS Full Name Muhammad Aslam Address Dept. of ELT& Linguistics ,IER, University of the Punjab, Lahore Cell 03224191400 Email [email protected] Date of Birth 15-01-1964 Institution Univ. of the Punjab EMPLOYMENT HISTORY (Full time only) Sr.# INSTITUTION DESIGNATION YEAR TOTAL FROM TO YEARS 1. University of the Punjab, Lahore Lecturer (BPS-18) 01-08- 31-7- 2001 2017 2. University of the Punjab, Lahore Senior Lecturer 1-8- This (BPS-19) 2017 day Total Experience: __19years 04 months________________ EDUCATION (Start from the last degree) Sr.# LEVEL SUBJECT INSTITUTION YEAR OF COMPLETION 1. PhD English (Linguistics) IIU, Islamabad Thesis in foreign evaluation 2. MPhil TESL Beaconhouse National University, 2012 Lahore 3. MA English Literature. Islamia University, Bahawal Pur 1994 4. MA TEFL AIOU, Islamabad 2007 5. MA Education IER, University of the Punjab, 1996 Lahore OTHER FORMAL TRAINING Sr.# INSTITUTION TYPE OF YEARS CERTIFICATE/ TRAINING ATTENDED DIPLOMA 1. AIOU, Islamabad English Language 1998 PGD,TEFL Teaching Distinctions Won Gold Medal for first position in MPhil TESL in 2012 from BNU, Lahore. SUBJECTS TAUGHT Sr.# SUBJECT LEVEL INSTITUTION 1. Issues in Syntax MPhil AL (Adjunct LIFE, University of Lahore, Lahore faculty) 2. Descriptive Syntax; MA Dept. of ELT & Linguistics, PU, Lahore Introduction to Linguistics 3. Generative Syntax & MA Dept. of ELT & Linguistics, PU, Lahore Morphology; Phonetics & Phonology 4. Lexicology: BS English (Adjunct University of Education, Lahore Psycholinguistics; faculty) Historical Linguistics; Stylistics. 5. Sociolinguistics MPhil AL (Adjunct MUL, Lahore (in progress) faculty). 6 Language Assessment; MPhil TESL (Adjunct BNU, Lahore General Linguistics faculty) THESIS SUPERVISION (If Applicable) Sr.# LEVEL TITLE OF RESEARCH INSTITUTION YEAR (MS/Ph.D.) 1. -

The Career Guide (Intermediate Students)

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/318340843 The Career Guide (Intermediate Students) Book · July 2017 CITATIONS READS 0 14,433 2 authors: Aftab Ahmad Rabail Hassan Toor National Academy of Young Scientists (NAYS), … University of the Punjab 85 PUBLICATIONS 132 CITATIONS 5 PUBLICATIONS 3 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Tissue Engineering of Heart and Liver View project Osteogenic Activity of Cissus quadrangularis View project All content following this page was uploaded by Aftab Ahmad on 11 July 2017. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. The Career Guide Compiled By: Dr. Aftab Ahmad Chattha Ms. Rabail Hassan Toor Edited By: Tabinda Salman CoverPage: Sufian Ahmad Publishing Date: July, 2017 Edition: Ist Publisher: National Academy of Young Scientists (NAYS), Pakistan Contact: NAYS office, 2nd Floor, STC, University of the Punjab, New Campus, Lahore, Punjab, Pakistan. +92-300-7402202, [email protected], [email protected] (No part of this book can be copied or printed without prior permission from the publisher) NAYS- Pakistan Contents Introduction 03 Degree options: Medical and related fields 05 Agriculture and Life sciences 07 Engineering 08 Natural Sciences 09 Social Sciences 10 List of public Universities 11 List of Private Universities 14 List of Scholarship Funding Agencies, NGO's, Foundations in Pakistan providing Study Funds and Scholarships 17 P a g e | 2 The Career Guide… NAYS- Pakistan The Career Guide (Intermediate Students) Choosing a definite career after intermediate studies is the most important decision a student has to make, as whole future of the student depends on it. -

The-Career-Guide-Book.Pdf

The Career Guide Compiled By: Dr. Aftab Ahmad Chattha Ms. Rabail Hassan Toor Edited By: Tabinda Salman CoverPage: Sufian Ahmad Publishing Date: July, 2017 Edition: Ist Publisher: National Academy of Young Scientists (NAYS), Pakistan Contact: NAYS office, 2nd Floor, STC, University of the Punjab, New Campus, Lahore, Punjab, Pakistan. +92-300-7402202, [email protected], [email protected] (No part of this book can be copied or printed without prior permission from the publisher) NAYS- Pakistan Contents Introduction 03 Degree options: Medical and related fields 05 Agriculture and Life sciences 07 Engineering 08 Natural Sciences 09 Social Sciences 10 List of public Universities 11 List of Private Universities 14 List of Scholarship Funding Agencies, NGO's, Foundations in Pakistan providing Study Funds and Scholarships 17 P a g e | 2 The Career Guide… NAYS- Pakistan The Career Guide (Intermediate Students) Choosing a definite career after intermediate studies is the most important decision a student has to make, as whole future of the student depends on it. After successful completion of intermediate studies, one has to choose for a professional degree that will define the future career of the student. Due to lack of experience, awareness and proper guidance, the students can end up choosing the wrong career. In Pakistan, there is an impression that only medical and engineering fields are worth joining, but there are a limited number of seats and not all candidates can get admission in these fields. The tradition has to be changed, as there are many important professional degrees in every field where one can achieve good reputation not only in your country but also in the world.Most of the students who cannot secure admission in medical or engineering field waste important time of their life worrying about it, instead of exploring themselves and choosing some other field of their interest for further studies.