The Baffin Writers' Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ENGLISH 261 Summer18

ENGLISH 261 ARCTIC ENCOUNTERS 4-6:10, Gaige Hall 303 (days vary) Dr. Russell A. Potter http://eng261.blogspot.com There are few places left on earth where simply going there seems extraordinary – but a trip north of the Arctic Circle still seems to signify the experience of something astonishing. This course takes up the history of human exploration and interaction in the Arctic, from the early days of the nineteenth century to the present, with a focus on contact between European and American explorers and the Eskimo, or Inuit as they are more properly known today. We read first-hand accounts and view dramatic films and documentaries that recount these histories, both from the Western and the Inuit side of the story. Each week, we’ll have new readings both in our books and online, and a response to one of that week’s blog posts is due. There will also be a final paper of 4-6 pages on a topic of the student’s choosing related to our course subjects. This summer, we’ll also have an unusual opportunity: I’ll be teaching the second half of the course from on board a ship in the Arctic! As I have in past summers, I’ll be aboard the research vessel Akademik Ioffe as part of a team of experts working with passengers on a series of expedition cruises. I’ll be in the Canadian Maritimes, Newfoundland and Labrador, and eventually in Nunavut heading up the coast of Baffin Island. I’ll be posting text, and some pictures (the limited bandwidth of the ship’s e-mail means that these will mostly be rather small ones) and posting/commenting on our class blog. -

Inuit Education in the Far North of Canada

Heather E. McGregor. Inuit Education and Schools in the Eastern Arctic. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2010. 220 pp. $85.00, cloth, ISBN 978-0-7748-1744-8. Reviewed by Jon Reyhner Published on H-Education (August, 2010) Commissioned by Jonathan Anuik (University of Alberta) Heather McGregor’s Inuit Education and Teachers recruited from southern Canada to Schools in the Eastern Arctic examines the history staff village schools lacked training in cross-cul‐ of Inuit education in the Far North of Canada. She tural education and usually did not stay long finds that colonization only occurred there in enough to learn much about the Inuit. Besides the earnest after World War II and she divides the Far language gap these teachers faced, there was a North’s history of education into the pre-1945 tra‐ fundamental contradiction between their values ditional, 1945-70 colonial, 1970-82 territorial, and and those expressed in the teaching materials 1982-99 local periods. Throughout the book the they used, and Inuit values. McGregor quotes author demonstrates a real effort to complement Mary A. Van Meenen’s 1994 doctoral dissertation and contrast the reports of government bureau‐ stating, “The core of the problem was that neither cracies and outside researchers with the voice of the federal nor territorial governments under‐ the Inuit. stood the peoples they were trying to educate” (p. A century ago, missionaries entered the Arctic 87). The resulting culturally assimilationist educa‐ and often stayed long enough to learn the Inuit tion led to a loss of Inuit cultural identity and languages. Around 1900 missionaries developed a “widespread … spousal abuse, alcoholism, and syllabary for Inuktitut and reading and writing it suicide” (p. -

Nunavut, a Creation Story. the Inuit Movement in Canada's Newest Territory

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE August 2019 Nunavut, A Creation Story. The Inuit Movement in Canada's Newest Territory Holly Ann Dobbins Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Dobbins, Holly Ann, "Nunavut, A Creation Story. The Inuit Movement in Canada's Newest Territory" (2019). Dissertations - ALL. 1097. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/1097 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract This is a qualitative study of the 30-year land claim negotiation process (1963-1993) through which the Inuit of Nunavut transformed themselves from being a marginalized population with few recognized rights in Canada to becoming the overwhelmingly dominant voice in a territorial government, with strong rights over their own lands and waters. In this study I view this negotiation process and all of the activities that supported it as part of a larger Inuit Movement and argue that it meets the criteria for a social movement. This study bridges several social sciences disciplines, including newly emerging areas of study in social movements, conflict resolution, and Indigenous studies, and offers important lessons about the conditions for a successful mobilization for Indigenous rights in other states. In this research I examine the extent to which Inuit values and worldviews directly informed movement emergence and continuity, leadership development and, to some extent, negotiation strategies. -

Southern Exposure: Belated Recognition of a Significant Inuk Writer-Artist

SOUTHERN EXPOSURE: BELATED RECOGNITION OF A SIGNIFICANT INUK WRITER-ARTIST Michael P.J. Kennedy Department of English University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan Canada, S7N 5A5 Abstract / Resume Alootook Ipellie was born on Baffin Island in 1951 and grew up during a period of Inuit transition. He experienced first-hand the evolving nature of Inuit culture as the values and attitudes of the South moved northward. Through his use of visual art, non-fiction, poetry, and fiction, he has imaginatively captured Inuit transitions in the latter half of the 20th century. This article provides readers with an introduction to this uniquely talented writer-artist and his work. Alootook Ipellie est né à l'Ile Baffin en 1951 et a grandi pendant une période de transtition pour les Inuits. Il a vécu de première main l'évolution de la nature de la culture Inuit de même que le mouvement des valeurs et attitudes du Sud vers le Nord. En se servant de l'art visuel, de la poésie, et de la fiction, il a saisi de manière imaginative les périodes de transition inuit dans la deuxième moitié du vingtième siècle. L'article offre ua lecteur un premier contact avec cet écrivain-artiste au talent unique ainsi qu'avec son oeuvre. 348 Micheal P.J. Kennedy For well over two decades, an Inuk artist has been creating visual and verbal images which epitomize the reality of being Inuit in the latter half of the 20th century. Yet for well over two decades, the imaginative creations of Alootook Ipellie have been largely overlooked by Canadians living outside the Arctic. -

Cooperation Between First Peoples and German Canadianists

Cooperation Between First Peoples and German Canadianists An Outreach Success Story from the Greifswald Canadian Studies Program (CGSP) From October 26-29th, 2007, the Greifswald Canadian Studies Program at the University of Greifswald, Germany hosted a conference titled “The Métis, An Aboriginal Canadian Nation: An ELT Project for German Secondary Schools”, which attracted scholars, teachers, specialists, university students and experts from Germany, Poland, Switzerland, Finland and Canada. This two day event along with visit from Métis educator Rene Inkster from Mission, British Colombia, presented the capstone of a Métis school project in local high schools, which have been developed and taught by teachers, students and graduates from the Institute of British and North American Studies under the supervision of Dr. Hans Enter, in cooperation with Dr. Hartmut Lutz and other members of Greifswald Canadian Studies Program. This project is the result of a long time collaboration between Greifswald Canadianists and Métis and Aboriginal scholars and teachers in Canada. This relationship began in 1992 when with the help of the Department of Foreign Affaires and International Trade (DFAIT), the Canadian Embassy and the Association for Canadian Studies in German-Speaking Countries, Dr. Anette Brauer organized an international conference aptly titled Peoples in Contact. Since then, cooperation between scholars and Métis and Aboriginal institutions never faltered and received constant support from the Canadian population along with Métis and Aboriginal artists and educators. The following examples give an idea of the scope of the cooperation between Métis, Aboriginals and German Canadianists: • In addition to lectures from renowned Aboriginal authors such as Jeannette Armstrong, Alootook Ipellie, Lee Maracle, Daniel David Moses and Drew Hayden Taylor, guests Métis professors visited such as painter Professor Bob Boyer and author Dr. -

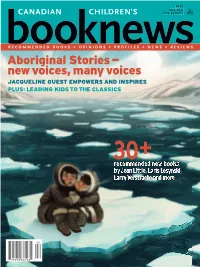

Aboriginal Stories — New Voices, Many Voices JACQUELINE GUEST EMPOWERS and INSPIRES PLUS: LEADING KIDS to the CLASSICS

$4.95 FALL 2012 VOL. 35 NO. 4 RECOMMENDED BOOKS + OPINIONS + PROFILES + NEWS + REVIEWS Aboriginal Stories — new voices, many voices JACQUELINE GUEST EMPOWERS AND INSPIRES PLUS: LEADING KIDS TO THE CLASSICS + 30 04 7125274 86123 .ASO !S=N@O 2AREASO !QPDKN )HHQOPN=PKN $ENA?PKNU !J@IKNA If you love Canadian kids’ books, go to the source: bookcentre.ca The Canadian Children’s Book Centre CONTENTS THISI ISSUE booknews Fall 2012 Volume 35 No. 4 7 Seen at... Fall brings a harvest of literary celebrations. Richard Scrimger (Ink Me) Editorr Gillian O’Reilly entertains his audience at the Telling Tales Festival held in Hamilton Copy Editor and Proofreaderr Shannon Howe Barnes Design Perna Siegrist Design in September. For more literary festivities, see page 7. Advertising Michael Wile Editorial Committee Peter Carver, Brenda Halliday, Merle Harris, Diane Kerner, Cora Lee, Carol McDougall, Liza Morrison, Shelley Stagg Peterson, Charlotte Teeple, Gail Winskill This informative magazine published quarterly by the Canadian Children’s Book Centre is available by yearly subscription. Single subscription — $24.95 plus sales tax (includes 2 issues of Best Books for Kids & Teens) Contact the CCBC for bulk subscriptions and for US or overseas subscription rates. Fall 2012 (November 2012) Canadian Publication Mail Product Sales Agreement 40010217 Published by the Canadian Children’s Book Centre ISSN 1705 – 7809 For change of address, subscriptions, or return of undeliverable copies, contact: The Canadian Children’s Book Centre 40 Orchard View Blvd., Suite 217 Toronto, ON M4R 1B9 Tel 416.975.0010 Fax 416.975.8970 Email [email protected] Website www.bookcentre.ca Review copies, catalogues and press releases should be sent to the Editor at: [email protected] am ngh or to Gillian O’Reilly c/o the above address. -

Footprints 2: a Second Comprehensive Report of the Nunavut Implementation Commission

Footprints.-- 2 , A seiond comprehensive report of the Nunavut Implementation Commission 4 t I I A Second Comprehensive Report from the Nunavut Implementation Commission to the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, Government of the Northwest Tem'tories and Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated Concerning the Establishment of the Nunavut Government Letter of Transmittal from the Chairman of the NIC to the Minister of the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, the Government Leader of the Northwest Territories and the President of Nunavut Tunngavik ... Incorporated. .................................. ill Table of Contents .................................v List of Appendices ...............................vii ... Glossary ......................................vlll Body of Report .................................. 1 ONunavut lmplernentation Commission 1996. Quotation with appropriate credit is encouraged. This publication reproduces, with minor editorial amendments, a report submitted to the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, Government of the Northwest Territories and Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated under cover of a letter dated October 21,1996. ISBN 1-896548-20-2 Cette publication existe aussi en franqais sous le titre : trL1empreintede nos pas dans la neige fraiche, Volume 2,). Cover Illustration: Alootook Ipellie French translation: Marie-C6cile Brasseur and Daniel Seguin Printed in Canada by: Bradda Printing Srvices Inc. oa9' L<LTC~>~~~ Nunavut Hivumukpalianikhaagut Katimayit Nunavut Implementation -

THE DIARY of ABRAHAM ULRIKAB: TEXT and in Essays at the Beginning and End of the Book, Profes- CONTEXT

330 • REVIEWS Research Center at Ohio State University, are well cap- see them. Soon after their arrival in Germany, both fami- tioned. Unfortunately, they do not include identifying lies came to regret their decision to spend a year abroad. catalogue numbers. Abraham wrote that the Inuit found the crowds unpleasant, Nasht’s book has deservedly been selected by the South tired of their duties, suffered mistreatment at the hands of Australia Big Book Club as its April 2006 Book-of-the- their employers, caught a variety of ailments, and were Month Club Selection. I heartily recommend it to all who desperately homesick. are interested in Arctic and Antarctic explorers, explora- Professor Lutz and his students located a number of tion, and history. other documents that provide additional information about this sad chapter in Inuit-Western history. The documents Stuart E. Jenness include Moravians’ letters expressing concern about the 9-2051 Jasmine Crescent Hagenbeck arrangement, newspaper articles reporting on Ottawa, Ontario, Canada the Inuit exhibition, the physician Rudolf Virchow’s paper K1J 7W2 detailing physical and behavioral attributes of individual family members, and clothing advertisements making ref- (Stuart E. Jenness is the author of The Making of an erence to the Inuit’s attire. These documents, along with Explorer: George Hubert Wilkins and the Canadian Arctic Abraham’s letters and diary, have been translated into Expedition, 1913–1916, published by McGill Queen’s English and form the body of the publication. Historic University Press in 2004.) drawings and photographs of the eight Inuit and Alootook Ipellie’s cover artwork complement the text and reinforce Abraham’s first-person voice. -

2005 the Diary of Abraham Ulrikab

Document généré le 25 sept. 2021 05:46 Études/Inuit/Studies LUTZ, Hartmut (ed.), 2005 The Diary of Abraham Ulrikab: Text and Context, Translated by Hartmut Lutz and students from the University of Greifswald, Germany, Ottawa, University of Ottawa Press, 100 pages. Peter C. Evans Problématiques des sexes Gender issues Volume 30, numéro 1, 2006 URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/016164ar DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/016164ar Aller au sommaire du numéro Éditeur(s) Association Inuksiutiit Katimajiit Inc. Centre interuniversitaire d'études et de recherches autochtones (CIÉRA) ISSN 0701-1008 (imprimé) 1708-5268 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer ce compte rendu Evans, P. C. (2006). Compte rendu de [LUTZ, Hartmut (ed.), 2005 The Diary of Abraham Ulrikab: Text and Context, Translated by Hartmut Lutz and students from the University of Greifswald, Germany, Ottawa, University of Ottawa Press, 100 pages.] Études/Inuit/Studies, 30(1), 201–205. https://doi.org/10.7202/016164ar Tous droits réservés © La revue Études/Inuit/Studies, 2006 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. https://www.erudit.org/fr/ les sciences sociales. Laugrand montre clairement que la réception du christianisme par les Inuit a été le résultat d'un long processus dynamique, complexe et multidimensionnel. -

Mitiarjuk's Sanaaq and the Politics of Translation in Inuit Literature

Arctic Solitude: Mitiarjuk’s Sanaaq and the Politics of Translation in Inuit Literature Keavy Martin erhaps it is the influence of the grant writing that scholars are obliged to do in order to earn our bread and butter, but it seems that much of our energy in literary studies goes into advo- Pcating for the reading that we have most recently been doing. We thrive on identifying gaps in the critical literature, and then on zealously draw- ing other people’s attention to these oversights. “Too often,” we say, or “for too long, the work of (insert author here) has gone unrecognized!” This kind of tactic, however — what might be called remedial or salvage literary criticism — is arguably quite valid when informed by the appro- priate political framework: for instance, when the oversight that we are protesting has happened as the result of shortsightedness or prejudice or Eurocentrism in the academy. What we read, after all, and what we choose to canonize (and finance) by inclusion on university reading lists says much about our values — and those of our institutions. The process of opening up the canon to include, first, works by Canadian writers (itself, at one time, a radical move) and, later, works by Canadian writers belonging to demographics other than the two “founding” French and English nations has been an important agent in the rise of both multiculturalism and the Aboriginal1 rights move- ment. Today, almost any Canadian literature course will include at least one text by an Aboriginal writer: generally by Thomas King, Eden Robinson, or Tomson Highway. -

Arctic and Antipodes

University of Wollongong Thesis Collections University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Year Indigenous diasporic literature : representations of the Shaman in the works of Sam Watson and Alootook Ipellie Kimberley McMahon-Coleman University of Wollongong McMahon-Coleman, Kimberley, Indigenous diasporic literature : representations of the Shaman in the works of Sam Watson and Alootook Ipellie, PhD thesis, Faculty of Arts, University of Wollongong, 2009. http://uow.ro.edu.au/theses/786 This paper is posted at Research Online. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/786 INDIGENOUS DIASPORIC LITERATURE: REPRESENTATIONS OF THE SHAMAN IN THE WORKS OF SAM WATSON AND ALOOTOOK IPELLIE A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY from UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG By KIMBERLEY McMAHON-COLEMAN B.A. (Hons.), G. Dip. Ed FACULTY OF ARTS 2009 CERTIFICATION I, Kimberley L. McMahon-Coleman, declare that this thesis, submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Faculty of Arts, University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Kimberley L McMahon-Coleman April 14, 2009 CERTIFICATION I, Kimberley L. McMahon-Coleman, declare that this thesis, submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Faculty of Arts, University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced -

Drawing Inuit Satiric Resilience: Alootook Ipellie's Decolonial

Document generated on 09/30/2021 4:35 a.m. esse arts + opinions Drawing Inuit Satiric Resilience: Alootook Ipellie’s Decolonial Comics Dessiner la résilience satirique des Inuits : les caricatures décoloniales d’Alootook Ipellie Amy Prouty Esquisse Sketch Number 93, Spring 2018 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/88004ac See table of contents Publisher(s) Les éditions esse ISSN 0831-859X (print) 1929-3577 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Prouty, A. (2018). Drawing Inuit Satiric Resilience: Alootook Ipellie’s Decolonial Comics / Dessiner la résilience satirique des Inuits : les caricatures décoloniales d’Alootook Ipellie. esse arts + opinions, (93), 30–37. Tous droits réservés © Amy Prouty, 2018 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Alootook Ipellie’s Decolonial Comics Amy Prouty Esse Drawing is the medium that eventually broke the barrier between Inuit artists and the global contemporary art world. Since the mid-2000s, the works of graphic artists such as Tim Pitsiulak, Annie Pootoogook, and Jutai Toonoo have no longer been viewed as commercial gallery “oddities” and are often featured in prominent art institutions and biennales. Although each artist works in a markedly different aesthetic, they are united in their use of satire.