U .S. Army 1945-1960

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE ARIZONA ROUGH RIDERS by Harlan C. Herner a Thesis

The Arizona rough riders Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Herner, Charles Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 04/10/2021 02:07:43 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/551769 THE ARIZONA ROUGH RIDERS b y Harlan C. Herner A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1965 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of require ments for an advanced degree at the University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under the rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the dean of the Graduate College when in his judgment the proposed use of this material is in the interests of scholarship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. SIGNED: MsA* J'73^, APPROVAL BY THESIS DIRECTOR This thesis has been approved on the date shown below: G > Harwood P. -

The Origins of the Imperial Presidency and the Framework for Executive Power, 1933-1960

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 4-2013 Building A House of Peace: The Origins of the Imperial Presidency and the Framework for Executive Power, 1933-1960 Katherine Elizabeth Ellison Western Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the Political History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Ellison, Katherine Elizabeth, "Building A House of Peace: The Origins of the Imperial Presidency and the Framework for Executive Power, 1933-1960" (2013). Dissertations. 138. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/138 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BUILDING A HOUSE OF PEACE: THE ORIGINS OF THE IMPERIAL PRESIDENCY AND THE FRAMEWORK FOR EXECUTIVE POWER, 1933-1960 by Katherine Elizabeth Ellison A dissertation submitted to the Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History Western Michigan University April 2013 Doctoral Committee: Edwin A. Martini, Ph.D., Chair Sally E. Hadden, Ph.D. Mark S. Hurwitz, Ph.D. Kathleen G. Donohue, Ph.D. BUILDING A HOUSE OF PEACE: THE ORIGINS OF THE IMPERIAL PRESIDENCY AND THE FRAMEWORK FOR EXECUTIVE POWER, 1933-1960 Katherine Elizabeth Ellison, Ph.D. Western Michigan University, 2013 This project offers a fundamental rethinking of the origins of the imperial presidency, taking an interdisciplinary approach as perceived through the interactions of the executive, legislative, and judiciary branches of government during the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s. -

Autographs – Auction November 8, 2018 at 1:30Pm 1

Autographs – Auction November 8, 2018 at 1:30pm 1 (AMERICAN REVOLUTION.) CHARLES LEE. Brief Letter Signed, as Secretary 1 to the Board of Treasury, to Commissioner of the Continental Loan Office for the State of Massachusetts Bay Nathaniel Appleton, sending "the Resolution of the Congress for the Renewal of lost or destroyed Certificates, and a form of the Bond required to be taken on every such Occasion" [not present]. ½ page, tall 4to; moderate toning at edges and horizontal folds. Philadelphia, 16 June 1780 [300/400] Charles Lee (1758-1815) held the post of Secretary to the Board of Treasury during 1780 before beginning law practice in Virginia; he served as U.S. Attorney General, 1795-1801. From the Collection of William Wheeler III. (AMERICAN REVOLUTION.) WILLIAM WILLIAMS. 2 Autograph Document Signed, "Wm Williams Treas'r," ordering Mr. David Lathrop to pay £5.16.6 to John Clark. 4x7½ inches; ink cancellation through signature, minor scattered staining, folds, docketing on verso. Lebanon, 20 May 1782 [200/300] William Williams (1731-1811) was a signer from CT who twice paid for expeditions of the Continental Army out of his own pocket; he was a selectman, and, between 1752 and 1796, both town clerk and town treasurer of Lebanon. (AMERICAN REVOLUTION--AMERICAN SOLDIERS.) Group of 8 items 3 Signed, or Signed and Inscribed. Format and condition vary. Vp, 1774-1805 [800/1,200] Henry Knox. Document Signed, "HKnox," selling his sloop Quick Lime to Edward Thillman. 2 pages, tall 4to, with integral blank. Np, 24 May 1805 * John Chester (2). ALsS, as Supervisor of the Revenue, to Collector White, sending [revenue] stamps and home distillery certificates [not present]. -

Displacement and Equilibrium: a Cultural History of Engineering in America Before Its “Golden Age”

Displacement and Equilibrium: A Cultural History of Engineering in America Before Its “Golden Age” A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY David M. Kmiec IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Bernadette Longo, Adviser August 2012 Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................. 1 1 Using historical context to contextualize history: The ideology of cultural history ........................................................................... 12 Motivation and methodology for a cultural history of American engineering ......................................................................................... 16 2 National service and public work: Military education and civilian engineering ......................................................... 23 Early modern France and the origins of military engineering ................................ 24 Military engineering and the American Revolution ................................................ 30 Civilian engineering as rationale for maintaining a military in peacetime .............................................................................................. 37 Engineering union in sectionalist America .............................................................. 51 3 The self-made engineer goes to school: Institutionalized education(s) for engineers ......................................................... 59 Colleges at the -

F:\...\02 S Vladeck Wp9 M

Ludecke’s Lengthening Shadow: The Disturbing Prospect of War Without End Stephen I. Vladeck* Wars have typically been fought against proper nouns (Germany, say) for the good reason that proper nouns can surrender and promise not to do it again. Wars against common nouns (poverty, crime, drugs) have been less successful. Such opponents never give up. The war on terrorism, unfortunately, falls into the second category.1 * * * Particularly when the war power is invoked to do things to the liberties of people . the constitutional basis should be scrutinized with care. I would not be willing to hold that war powers may be indefinitely prolonged merely by keeping legally alive a state of war that had in fact ended. I cannot accept the argument that war powers last as long as the effects and consequences of war, for if so they are permanent . .2 INTRODUCTION The “war” on terrorism may never end.3 At a minimum, it shows no signs of ending any time soon. Although this reality is an unpleasant one for many civil libertarians today, it is also difficult to refute. Just what will mark the conclusion of hostilities? It seems unlikely that there is an entity whose “surrender” would mark an obvious “end” of combat. Even if there were such an entity, there do not appear to be clearly identifiable objectives that allow for the successful completion of the conflict. There is no physical territory to conquer, no clear leadership structure to topple, no Reichstag over which to fly a foreign flag. * Associate Professor, University of Miami School of Law; Associate Professor (as of Fall 2007), American University Washington College of Law. -

House of Representatives

1946 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE 9245 UNITED STATES PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE spiritual ideals and principles. Fill us gentleman from Ohio [Mr. SMITH] to act APP-OINTMENTS IN THE REGULAR CORPS, with a dauntless faith in the wisdom and as a conferee in place o:f- the gentleman To be assistant sanitary engineers, effective power of Thy spirit, for Thou' alone canst from Michigan [Mr. CRAWFORD] and the date o/ oath of office touch to finer issues the creative and Senate will be notified of the action of John R. Thoman curative forces of our civilization. Thou the House. Richard J. Hammerstrom alone canst bring to fulfillment our deep· There was no objection. To be senior assistant sanitary engineers, est yearnings and highest hopes. EXTENSION OF REMARKS effective date of oath of office We humbly confess that · again and Richard S. Green Ralph C. Palange again our faith is eclipsed and shadowed · Mr. RIVERS asked and was given per Leonard B. Dworsky Graham Walton by doubt and we become disheartened mission to extend his remarks in the Francis B. Elder Howard W. Chapman and discouraged and feel that we have RECORD in tw(} instances, in one to in- Conrad P . Straub Gerald W. Ferguson been deceived by delusions. God forbid . elude an editorial from the Mobile Press· Elroy K. Day Richard S. Mark Register, and in the other an article by Charles T. Carnahan that we should ever be guilty of that pes simistic cynicism which believes that hu Mr. Frank A. Godchaux, president of the IN THE ARMY man nature is basically brutal and self Louisiana State Rice Milling Co. -

Official U. S. Bulletin

We liq/1;;sitilfi‘iinancewOuiriMen Who_Are Fighting in France PUBLISHED DAILY UNDER ORDER OF THE PRESIDENT BY THE COMMJ’ITEE ON PUBLIC INFOBBIATION GEORGE CREEL CHAIRMAN ' Vol. 1. MONDAY, ..“4. 1917. N0. 189. \VASHINGTON, OCTOBER U. S. WOMEN lN ARGENTINA FAMILIES OF MEN WHO DEED 0R WERE DiSABLED GET $100,000 FOR RED CROSS WHEN U. S. TRANSPORT WAS SUNK BY U-BOAT WELL The Department of State authorizes the SHARE EN BENEFZTS OF NEW WAR lNgURAiNCE ACT following: A telegram from the American ambas Loss of Vessel, Says Treasury Department Statement, Furnishes Striking sador in Buenos Aires that a pa states Lesson in of and Automatic triotic society of American women, or Object Benefit Compensation insurance Pro ganized when the United States entered visions of the Law—Summary Covering Various Cases Prepared. the war, held a two days” fair in Buenos Aires and cleared $100,000 in gold which The Treasury Department authorizes to come in large measure from the sale of will be sent to the American Red Cross. bonds of the second Liberty loan. This result was largely due to the gener the following: In view of the importance of the new osity of Argentinians, who attended in The sinking of the American transport law to those in military and naval service large numbers. Many of them gave their Antilles by a German submarine, with the and their families and dependents, the fol own cattle for the benefit of the fund. loss of 70 lives, has furnished a striking ' lowing oflicial summary covering; various The minister for foreign affairs. -

The Memoirs of Gen. Joseph Gardner Swift, LL.D., U.S.A., First

STEPHEN B= WEEKS CUS5 0FBa6;PH.nmE JOHNS HOPKiNS UNWERSnY OF THE m WEEKS COULECTKUN CB S7T °'' CHAPEL VZ i™?,',!7. " = " HILL 0003270328 This book must not be token from the Library building. OCT2? rj Form No. 471 j^arc m^ <^^^-^^^!!^l^^^>ii5y ^(ZZ^StT/C IUjL /^ /^fo. THE MEMOIRS OF dEN. Joseph Gardner Swift, LL,D„U,S, A, FIRST GRADUATE OF THE United States Military Academy, West Point, Chief Engineer U. S. A. from 1812 ro 18 18. 1800 1865. To which is added a Genealogy of tlie Family of THOMAS SWIFT OF DORCHESTER, MASS., 1634, By HARRISON ELLERY, Member of the New England Historic Genealogical Society. PRIVATELY PRINTED. 1890. COI'VKIGHT, 1890, Bv Hahkison Eli.brv, INTRODUCTORY. The genealogy of the descendants of Thomas Swift of Dorchester, Massachusetts, which is added to these Memoirs, was written a few years ago, during leisure moments, with the intention of confining it to the first four generations of the family, and contributing the same to the pages of the New England Historical and Genealogical Register. It was to have been one of a series of genealogies of those families with which I am connected by marriage, and which I hoped from time to time to complete. But the temptation to all who engage in genealogical work to expand has been yielded to, and what was intended to be simply the history of the early generations of the family has become what this book contains. While corresponding with various members of the family on the subject of its history, I found in possession of the sons of the late General Swift, of the United States Army, his journal. -

Legal Authorities Supporting the Activities of the National Security Agency Described by the President

Office of the Attorney General Washington, D.C. January 19, 2006 The Honorable William H. Frist Majority Leader United States Senate Washington. D.C. 205 10 Dear Mr. Leader: As the President recently described, in response to the attacks of Septcmber I I"', he has authorized the National Security Agency (NSA) to intcrcept international comn~unicationsinto or out of the United States of persons linked to al Qaeda or an affiliated terrorist organization. The attached paper has becn prepared by the Department of Justice to provide a detailed analysis of the legal basis for those NSA activities dcscribcd by the President. As J have previously explained, these NSA activities al-e lawful in all respects. They represent a vital effort by the President to ensurc that we havc in place an early warning system to detect and prevent another catastrophic terrorist attack 011America. In the o~lgoingarmed conflict with al Qaeda and its allies, the President has the primary duty under the Constitution to protect the Anlerican people. The Constitution gives the President thc full authority necessary to carry out that solemn duty, and he has made clear that he will LIS~all authority available to him. consistent with the law, to protect the Nation. The President's authority to approve these NSA activities is confirmed and supplemented by Congress in the Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF), enacted on Septembcr 18, 2001. As discussed in depth in the attached paper, the President's use of his constitutional authority, as supplemented by statute in the AUMF, is consistent with the Foreign Intelligcnce Surveillance Act and is also fiilly protective of the civil liberties guaranteed by the Fourth Amendment. -

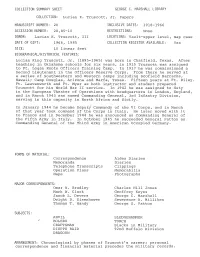

Inclusive Dates: 1918-1966 Restrictions: Collection

COLLECTION SUMMARY SHEET GEORGE C. MARSHALL LIBRARY COLLECTION: Lucian K. Truscott, Jr. Papers MANUSCRIPT NUMBER: 20 INCLUSIVE DATES: 1918-1966 ACCESSION NUMBER: 20,85-10 RESTRICTIONS: None DONOR: Lucian K. Truscott, III LOCATIONS: Vault-upper level, map case DATE OF GIFT: 1966, 1985 COLLECTION REGISTER AVAILABLE: Yes SIZE: 10 linear feet BIOGRAPHICAL/HISTORICAL FEATURES: Lucian King Truscott, Jr. (1895-1965) was born in Chatfield, Texas. After teaching in Oklahoma schools for six years, in 1915 Truscott was assigned to Ft. Logan Roots Officers Training Camp. In 1917 he was commissioned a Second Lieutenant in the Officers Reserve Corps. From there he served at a series of Southwestern and Western camps including Scofield Barracks, Hawaii; Camp Douglas, Arizona and Marfa, Texas. Fifteen years at Ft. Riley. Ft. Leavenworth and Ft. Myer as both iI1;structor and student prepared Truscott for his World War II service. In 1942 he was assigned to duty in the European Theater of Operations with headquarters in London, England, and in March 1943 was named Commanding General, 3rd Infantry Division, serving in this capacity in North Africa and Sicily. " I In January 1944 he became Deputy Commandy of the VI Corps, and in March of that year took command of the Corps in Italy. He later moved with it to France and in December 1944 he was announced as Commanding General of the Fifth Army in Italy. In October 1945 he succeeded General Patton as Commanding General of the Third Army in American Occupied Germany. FORMS OF MATERIAL: Correspondence Aides Diaries Memoranda Diaries Telephone Transcripts Clippings Operation Plans Memorabilia lvlaps Photographs MAJOR CORRESPONDENTS: Omar N. -

Making Democracy Work

Making Democracy Work: A Brief History of Twentieth-Century Federal Executive Reorganization BY BRIAN BALOGH, JOANNA GRISINGER AND PHILIP ZELIKOW In Consultation with: Peri Arnold Melvyn Leffler Ernest May Patrick McGuinn Paul Milazzo Sidney Milkis Edmund Russell Charles Wise Julian Zelizer Miller Center Working Paper in American Political Development University of Virginia July 22, 2002 2 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY OF KEY FINDINGS 5 ABOUT THIS WORKING PAPER 9 INTRODUCTION: Making History Work 11 PART I: Milestones in Twentieth-Century Executive Reorganization 15 • Early Efforts 17 • 1905-09 - Commission on Department Methods [Keep Commission] 20 • 1910-1923 - President’s Inquiry into Re-Efficiency and Economy; Commission on Economy and Efficiency [Taft Commission]; The Overman Act of 1918; Budget and Accounting Act of 1921; Joint Committee on Reorganization 21 • President’s Committee on Administrative Management [Brownlow Committee] 22 • Reorganizing for World War II; Commission on the Organization of the Executive Branch [Hoover Commission I] 26 • PACGO and the Commission on the Reorganization of the Executive Branch [Hoover Commission II] 33 • 1964 Task Force on Government Reorganization [Price Task Force] and 1967 Task Force on Government Organization [Heineman Task Force] 40 Advisory Council on Government Organization [Ash Council] • Carter’s Presidential Reorganization Project, Reagan’s Grace Commission, and Clinton’s National Performance Review, 1977 – 2000 44 PART II: Patterns 55 • Defending the Status Quo 57 • Catalysts for Reorganization 59 • Implementing Reorganization 61 o EPA Case Study 61 o The Department of Education Case Study 69 ABOUT THE AUTHORS 75 APPENDIX 81 Chart 1: Milestones in Twentieth-Century Executive Reorganization Chart 2. -

11 ADC 4044 Card 1 of 3 SOURCE: AFCF (0-1142) FILM: ARCH & APC MP 933' Ea Silent GENERAL MARK W CLARK ENTER Bologna, Italy 2

Signal Corps 11 DC4044-1 ADC 4044 SOURCE: AFCF (0-1142) Card 1 of 3 FILM: ARCH & APC MP 933' ea Silent GENERAL MARK W CLARK ENTER Bologna, Italy 22 April 1945 Excellent scenes, Gen Clark is greeted by Brig GenDouglas Packard, Deputy Chief of Staff (Br), 15th Army Group; Brig GenDonald W Brann, G-3, (Br) 15th Army Group upon entering city. The following persons are also in scenes: Polish Gen Wladyslaw Anders, Polish Maj Gen S Bohuz-Szyszko, US Maj Gen Geoffrey Keyes, US Maj Gen Willis D Crittenberger, US Maj Gen Charles L Bolte, US Maj Gen William G Live say and other unidentified British and American officers. Seq: Gen Anders shows Gen Clark a Nazi flag captured by the Polish Corps. VS, Gens Clark and Crittenberger at ceremony in wooded area.Gen Bolte, CG, 34th Div is awarded Silver Star. Record Group 111 Accession Number III-NAV-210 ARMY PICTORIAL CENTER, 35-11 35th Ave., LIC 1, NY ERBS/es Signal Corps 11 DC 044-2 ADC 4044 SOURCE: AFCF (0-1142) Card 2 of 3 FILM: ARCH & APC MP 933' ea Silent BOLOGNA MEETING Italy 22 Apr 45 Seq: 34th Div band playing for meeting of the Allied Generals in town square. CU, 34th Div band drummer. MS, Pan, Generals standing at attention. (Gens are those listed above.) PSYCHOLOGICAL WARFARE Bologna, Italy 22 Apr 45 Seq: Combat psychological warfare teams in jeeps drive thru streets. CU, soldier speaks into microphone while seated in jeep. Full screen view, Italian civilians applauding. In fg, a loudspeaker. LS, jeeps carrying Gens Clark, Keyes and Lt Gen Lucian K Truscott enter Plaza Emmanuel.