Descartes, Husserl and Radical Conversion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE PHILOSOPHY BOOK George Santayana (1863-1952)

Georg Hegel (1770-1831) ................................ 30 Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860) ................. 32 Ludwig Andreas Feuerbach (1804-1872) ...... 32 John Stuart Mill (1806-1873) .......................... 33 Soren Kierkegaard (1813-1855) ..................... 33 Karl Marx (1818-1883).................................... 34 Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862) ................ 35 Charles Sanders Peirce (1839-1914).............. 35 William James (1842-1910) ............................ 36 The Modern World 1900-1950 ............................. 36 Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) .................... 37 Ahad Ha'am (1856-1927) ............................... 38 Ferdinand de Saussure (1857-1913) ............. 38 Edmund Husserl (1859–1938) ....................... 39 Henri Bergson (1859-1941) ............................ 39 Contents John Dewey (1859–1952) ............................... 39 Introduction....................................................... 1 THE PHILOSOPHY BOOK George Santayana (1863-1952) ..................... 40 The Ancient World 700 BCE-250 CE..................... 3 Miguel de Unamuno (1864-1936) ................... 40 Introduction Thales of Miletus (c.624-546 BCE)................... 3 William Du Bois (1868-1963) .......................... 41 Laozi (c.6th century BCE) ................................. 4 Philosophy is not just the preserve of brilliant Bertrand Russell (1872-1970) ........................ 41 Pythagoras (c.570-495 BCE) ............................ 4 but eccentric thinkers that it is popularly Max Scheler -

Augustine on Heart and Life Essays in Memory of William Harmless, S.J

Augustine on Heart and Life Essays in Memory of William Harmless, S.J. Edited by John J. O’Keefe and Michael Cameron 10. Augustine’s Tragic Vision Paul M. Blowers, Emmanuel Christian Seminary at Milligan College Abstract This essay explores Augustine’s capacity to accommodate a tragic vision of human existence within his interpretation of the Christian revelation. Broadly speaking, for Augustine, sacred history combines the tragic necessity of self-inflicted human sinfulness with the benevolent necessity of the economy of divine grace. Augustine to some degree admired the pagan tragedians for compelling the attention and emotion of their audiences in confronting the ineluctability of evil (and other tragic themes), but their mimesis ultimately failed since it could not touch the reality conveyed in divine revelation. Two exegetical test cases, the story of Jephthah’s sacrifice of his daughter (Judges 11) and King Saul’s tragic heroics in 1 Samuel, exemplify how Augustine greatly profited from interpreting Scripture through a tragical lens. A whole other dimension of Augustine’s tragic vision appears in his attempt – inspired from his own early experience of staged tragedies in Carthage – to reenter ancient philosophical debates on tragedy and mimesis, and to revamp in Christian terms the tragic emotions, especially tragic pity as Christian mercy. 157 Augustine on Heart and Life Keywords: tragedy, necessity, theodicy, mimesis, catharsis, tragic pity Introduction “Tragedy” and “the tragic” are notoriously slippery terms both in historical and colloquial usage. Over the centuries “tragedy” has been employed to indicate, on the one hand, a genre of ancient drama – one depicting flawed human characters struggling heroically against the leviathan forces of cosmic necessity (in the form of abject suffering, death, etc.) – and, on the other hand, commonly today, a catastrophic event catching observers by utter surprise and upending their sense of cosmic stability and justice. -

Reconciling Aesthetic Philosophy and the Cartesian Paradigm Taryn Sweeney IDVSA

Maine State Library Digital Maine Academic Research and Dissertations Maine State Library Special Collections 2018 Aesthesis Universalis: Reconciling Aesthetic Philosophy and the Cartesian Paradigm Taryn Sweeney IDVSA Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalmaine.com/academic Recommended Citation Sweeney, Taryn, "Aesthesis Universalis: Reconciling Aesthetic Philosophy and the Cartesian Paradigm" (2018). Academic Research and Dissertations. 21. https://digitalmaine.com/academic/21 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Maine State Library Special Collections at Digital Maine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Academic Research and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Maine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AESTHESIS UNIVERSALIS: RECONCILING AESTHETIC PHILOSOPHY AND THE CARTESIAN PARADIGM Taryn M Sweeney Submitted to the faculty of The Institute for Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy November, 2018 ii Accepted by the faculty of the Institute for Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts in partial fulfillment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. COMMITTEE MEMBERS Committee Chair: Don Wehrs, Ph.D. Hargis Professor of English Literature Auburn University, Auburn Committee Member: Merle Williams, Ph.D. Personal Professor of English University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg Committee Member: Kathe Hicks Albrecht, Ph.D. Independent Studies Director Institute for Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts, Portland iii © 2018 Taryn M Sweeney ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe a profound gratitude to my advisor, Don Wehrs, for his tremendous patience, sympathy, and acceptance of my completely un-academic self as I approached this most ambitious and academic of undertakings. -

Virtue of Feminist Rationality

The Virtue of Feminist Rationality Continuum Studies in Philosophy Series Editor: James Fieser, University of Tennessee at Martin, USA Continuum Studies in Philosophy is a major monograph series from Continuum. The series features first-class scholarly research monographs across the whole field of philo- sophy. Each work makes a major contribution to the field of philosophical research. Aesthetic in Kant, James Kirwan Analytic Philosophy: The History of an Illusion, Aaron Preston Aquinas and the Ship of Theseus, Christopher Brown Augustine and Roman Virtue, Brian Harding The Challenge of Relativism, Patrick Phillips Demands of Taste in Kant’s Aesthetics, Brent Kalar Descartes and the Metaphysics of Human Nature, Justin Skirry Descartes’ Theory of Ideas, David Clemenson Dialectic of Romanticism, Peter Murphy and David Roberts Duns Scotus and the Problem of Universals, Todd Bates Hegel’s Philosophy of Language, Jim Vernon Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, David James Hegel’s Theory of Recognition, Sybol S.C. Anderson The History of Intentionality, Ryan Hickerson Kantian Deeds, Henrik Jøker Bjerre Kierkegaard, Metaphysics and Political Theory, Alison Assiter Kierkegaard’s Analysis of Radical Evil, David A. Roberts Leibniz Re-interpreted, Lloyd Strickland Metaphysics and the End of Philosophy, HO Mounce Nietzsche and the Greeks, Dale Wilkerson Origins of Analytic Philosophy, Delbert Reed Philosophy of Miracles, David Corner Platonism, Music and the Listener’s Share, Christopher Norris Popper’s Theory of Science, Carlos Garcia Postanalytic and Metacontinental, edited by James Williams, Jack Reynolds, James Chase and Ed Mares Rationality and Feminist Philosophy, Deborah K. Heikes Re-thinking the Cogito, Christopher Norris Role of God in Spinoza’s Metaphysics, Sherry Deveaux Rousseau and Radical Democracy, Kevin Inston Rousseau and the Ethics of Virtue, James Delaney Rousseau’s Theory of Freedom, Matthew Simpson Spinoza and the Stoics, Firmin DeBrabander Spinoza’s Radical Cartesian Mind, Tammy Nyden-Bullock St. -

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: for the END IS a LIMIT

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: FOR THE END IS A LIMIT: THE QUESTION CONCERNING THE ENVIRONMENT Ozguc Orhan, Doctor of Philosophy, 2007 Dissertation Directed By: Professor Charles E. Butterworth Department of Government and Politics Professor Ken Conca Department of Government and Politics This dissertation argues that Aristotle’s philosophy of praxis (i.e., ethics and politics) can contribute to our understanding of the contemporary question concerning the environment. Thinking seriously about the environment today calls for resisting the temptation to jump to conclusions about Aristotle’s irrelevance to the environment on historicist grounds of incommensurability or the fact that Aristotle did not write specifically on environmental issues as we know them. It is true that environmental problems are basically twentieth-century phenomena, but the larger normative discourses in which the terms “environmental” and “ecological” and their cognates are situated should be approached philosophically, namely, as cross-cultural and trans-historical phenomena that touch human experience at a deeper level. The philosophical perspective exploring the discursive meaning behind contemporary environmental praxis can reveal to us that certain aspects of Aristotle’s thought are relevant, or can be adapted, to the ends of environmentalists concerned with developmental problems. I argue that Aristotle’s views are already accepted and adopted in political theory and the praxis of the environment in many respects. In the first half of the dissertation, I -

Humanities the Issue of the Religious Dimension Of

PERIODYK NAUKOWY AKADEMII POLONIJNEJ 37 (2019) nr 6 HUMANITIES THE ISSUE OF THE RELIGIOUS DIMENSION OF HUMAN NATURE Jan Mazur Prof. PhD, Pontifical University of John Paul II in Kraków, e-mail: [email protected], http://orcid.org/0000-0002- 0548-0205, Poland Abraham Kome PhD, John Paul II International University of Bafang, e-mail: [email protected], orcid.org/0000-0001-7326-227X, Cameroon Abstract. This text is an attempt to answer the question of whether human nature needs religion. The author begins by presenting two concepts that are key in this discourse. These are the terms: religion and human nature. Then he undertakes an analysis of the problem, referring to the thoughts of religious experts: Rudolf Otto and Mircea Eliade and the philosopher Max Scheler. The subject of reflection is the definition of man as 'homo religiosus'. Questioning God's existence has a negative effect on human nature. This situation is illustrated by the views of two known philosophers, existentialists - Friedrich Nietzsche and Jean-Paul Sartre. Their vision of the world was marked by unbelief in God. Life experience teaches that human nature strives for transcendent reality, longs for God. Any departure from this tendency does not, however, invalidate the religious nature of man, but certainly falsifies it. It results in the conversion of an authentic sacrum into its substitutes. In conclusion, the author draws attention to the mystery of man and God, which should be recognized. It is only in this perspective that the problem indicated in the title can be considered. The inspiration for such thinking is the famous phrase of Saint Augustine of Hippo: 'The human soul is restless until it rests in God'. -

Pyrrhonism and Cartesianism – Episode: External World and Aliens

Philosophy department, CEU Budapest, Hungary Table of Contents Table of Contents ....................................................................................................................... 1 Table of Contents ....................................................................................................................... Pyrrhonism and 2 List of Abbreviations .................................................................................................................. 3 IntroductionCartesianism: ................................................................................................................................ external 4 1.Methodological and practical skepticism: theory and a way of life ........................................ 6 2.Hypothetical doubt,world practical concerns and and the existence aliens of the external world .................. 13 2.1. An explanation for Pyrrhonists not questioning the existence of the external world .... 18 In partial2.2. An analysisfulfillment of whether ofPyrrhonists the requirements could expand the scope for of theirthe skepticism to include the external world .................................................................................................... 21 3.Pyrrhonism, Cartesianism and degreesome epistemologically of Masters interesting of Artsquestions ..................... 27 Conclusion ................................................................................................................................ by Tamara Rendulic 37 References ............................................................................................................................... -

1 Shakespeare, the Critics, and Humanism 1

N OTES 1 Shakespeare, the Critics, and Humanism 1 . Virgil Heltzel, for example, in his “Introduction,” to Haly Heron’s The Kayes of Counsaile, A Newe Discourse of Morall Philosophie of 1579 (Liverpool: University of Liverpool Press, 1954), p. xv, describes the work as “bringing grave and sober moral philosophy home to men’s business and bosoms.” 2 . W i l l i a m B a l d w i n , A Treatise of Morall Philosophie . enlarged by Thomas Palfreyman , 20th ed. (London: Thomas Snodham, [?]1620), in Scholars’ Facsimiles and Reprints (Gainesville, Florida, 1967), with an introduction by Robert Hood Bowers. For the editions, see STC 1475–1640, Vol. I, 2nd ed., 1986, Nos. 1253 to 1269; and STC, 1641–1700 , 2nd ed., Vol. I, 1972, Nos. 548, 1620. Also see Bowers, “Introduction,” pp. v–vi. For the purposes of the present work, I will refer to the treatise as Baldwin’s rather than Baldwin- Palfreyman’s. The volume appears as “augmented” or “enlarged” by Palfreyman only with the fifth edition of 1555 (STC 1255.5) and the 1620 edition (first of the two in that year) says it is “the sixth time inlarged” by him but there has been no comparative study of what was originally Baldwin’s and what was Palfreyman’s and what the successive “enlargements” entailed. Baldwin’s treatise, along with Thomas Crewe’s The Nosegay of Morall Philosophie , for example, are purported sayings and quotations from a great num- ber of scattered Ancient and more recent writers, but they are organized into running dialogues or commentaries designed to express the compiler’s point of view rather than to transmit faith- fully the thought of the original writer. -

Two Varieties of Skepticism

1 2 3 4 Two Varieties of Skepticism 5 6 James Conant 7 8 This paper distinguishes two varieties of skepticism and the varieties of 9 philosophical response those skepticisms have engendered. The aim of 10 the exercise is to furnish a perspicuous overview of some of the dialec- 11 tical relations that obtain across some of the range of problems that phi- 12 losophers have called (and continue to call) “skeptical”. I will argue that 13 such an overview affords a number of forms of philosophical insight.1 14 15 16 I. Cartesian and Kantian Varieties of Skepticism – A First Pass 17 at the Distinction 18 19 I will call the two varieties of skepticism in question Cartesian skepticism 20 and Kantian skepticism respectively.2 (These labels are admittedly conten- 21 tious.3 Nothing of substance hangs on my employing these rather than 22 23 1 The taxonomy is meant to serve as a descriptive tool for distinguishing various 24 sorts of philosophical standpoint. It is constructed in as philosophically neutral a 25 fashion as possible. The distinctions presented below upon which it rests are 26 ones that can be deployed by philosophers of very different persuasions regard- 27 less of their collateral philosophical commitments. A philosopher could make use of these distinctions to argue for any of a number of very different conclu- 28 sions. Some of the more specific philosophical claims that I myself express sym- 29 pathy for in the latter part of this part (e.g., regarding how these varieties of 30 skepticism are related to one another) do, however, turn on collateral philo- 31 sophical commitments. -

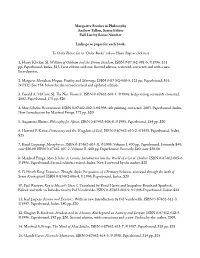

Marquette Studies in Philosophy Andrew Tallon, Series Editor Full List by Series Number

Marquette Studies in Philosophy Andrew Tallon, Series Editor Full List by Series Number Links go to pages for each book. To Order Please Go to “Order Books” tab on Home Page or click here 1. Harry Klocker, SJ. William of Ockham and the Divine Freedom. ISBN 0-87462-001-5. ©1996. 141 pp. Paperbound. Index. $15. First edition sold out. Second edition, reviewed, corrected and with a new Introduction. 2. Margaret Monahan Hogan. Finality and Marriage. ISBN 0-87462-600-5. 121 pp. Paperbound, $15. NOTE: See #34, below for the second revised and updated edition. 3. Gerald A. McCool, SJ. The Neo-Thomists. ISBN 0-87462-601-1. ©1994. 3rd printing, revised & corrected, 2003. Paperbound, 175 pp. $20 4. Max Scheler. Ressentiment. ISBN 0-87462-602-1.©1998. 4th printing, corrected, 2003. Paperbound. Index. New Introduction by Manfred Frings. 172 pp. $20 5. Augustine Shutte. Philosophy for Africa. ISBN 0-87462-608-0. ©1995. Paperbound. 184 pp. $20 6. Howard P. Kainz. Democracy and the ‘Kingdom of God.’ ISBN 0-87462-610-2. ©1995. Paperbound. Index. $25 7. Knud Løgstrup. Metaphysics. ISBN 0-87462-603-X. ©1995. Volume I. 400 pp. Paperbound. Formerly $40; now $20.00 ISBN 0-67462-607-2. Volume II. 400 pp. Paperbound. Formerly $40; now $20.00 8. Manfred Frings. Max Scheler. A Concise Introduction into the World of a Great Thinker. ISBN 0-87462-605-6. ©1996. Paperbound. Second edition, revised. Index. New Foreword by the author. $20 9. G. Heath King. Existence, Thought, Style: Perspectives of a Primary Relation, portrayed through the work of Søren Kierkegaard. -

Virtue and Civic Values in Early Modern Jesuit Education

journal of jesuit studies 5 (2018) 530-548 brill.com/jjs Virtue and Civic Values in Early Modern Jesuit Education Jaska Kainulainen University of Helsinki [email protected] Abstract The article suggests that by offering education in the studia humanitatis the Jesuits made an important contribution to early modern political culture. The Jesuit educa- tion facilitated the establishment of political rule or administration of civic affairs in harmony with Christian virtues, and produced generations of citizens who, while studying under the Jesuits, learned to identify piety with civic values. In educating such citizens the Jesuit pedagogues relied heavily on classical rhetoric as formulated by Cicero (106–43 bc), Quintilian (35–100), and Aristotle (384–322 bc). The article de- picts the Jesuits as civic educators and active members of respublica christiana. In so doing, the article emphasizes the importance of Jesuit education to early modern po- litical life. Keywords Jesuit education – civic values – virtue – rhetoric – Cicero – Renaissance humanism This article takes its cue from the observation that Jesuit education was based on the example laid down by the humanist educators of the Renaissance.1 The 1 For this argument, see John W. O’Malley, The First Jesuits (Cambridge, ma: Harvard University Press, 1993), 13–14, 208–12; Paul Grendler, Schooling in Renaissance Italy: Literacy and Learn ing, 1300–1600 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1989), 376–78; Marc Fumaroli, L’Âge de l’éloquence: Rhétorique et res literaria de la Renaissance au seuil de l’époque classique (Geneva: Droz, 2009), 175–76; Robert A. Maryks, Saint Cicero and the Jesuits: The Influence of the Liberal Arts on the Adoption of Moral Probabilism (Farnham: Ashgate, 2008), 77. -

Max Scheler, Formalism in Ethics and Non-Formal Ethics of Values

Notes Preface 1. Throughout this study I have opted to capitalise the noun 'man' to indicate a gender-free reference to the species, when the use of such expressions as 'he or she' and 'humankind' would be unnecessarily awkward. 2. Lewis Mumford, The City in History (New York: Harcourt, Brace and World, 1961),4. Introduction 1. Hereafter all references to this work will be cited in my text with the abbreviation FORM followed by the page number. All such citations will be to the third edition published in Bern by Franke Verlag in 1966. Unless otherwise noted all translations are mine. Readers who do not have access to the German text are advised to consult the English translation by Manfred S. Frings and Roger L. Funk: Max Scheler, Formalism in Ethics and Non-Formal Ethics of Values: A New Attempt toward the Foundation of an Ethical Personalism (Evanston: Illinois: Northwestern University Press, 1973). 2. While Frings and Funk have chosen to translate materiale as 'non formal', my sense is that this locution is both too inclusive and too negative. Many philosophical ethics could be loosely described as non-formal. What is more, to characterise Scheler's effort in terms of what it is not may obscure his concern to establish a distinctive and affirmative foundation for ethics in the experience of an a priori order of values that formal, ethical systems such as Kant's, deny. 3. See Manfred S. Frings, Max Scheler, A Concise Introduction Into the World of a Great Thinker (Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press, 1965), p. 105.