Cinematic Potentialities and the Student of Prague (1913) Matt Rossoni

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Information Issued by the Association of Jewish Refugees in Great Britain

Vol. XVI No. 3 March, 1961 INFORMATION ISSUED BY THE ASSOCIATION OF JEWISH REFUGEES IN GREAT BRITAIN I FAIRFAX MANSIONS, Offict and Coiuulting Heurs : FINCHLEY ROAO (Cornar Fairfax Road), LONDON. N.W.3 Mondaylo Thunday 10 a.nt.—l p.m. 3—6 p.nt. Telephon*: MAIda Val* 9096'7 (e*n*ral Officel Friday 10 a.m.—I p.m. MAIda Val* 4449 (Empioymant Ag*ncy and Social S*rvic*s D*pt.| About 2,945,000 claims have been lodged under the Federal Indemnification Law (BEG) of which A WIDE RANGE OF TASKS about 1,577,000 have been settled. The payments made are about 8,731 million DM and the total expenditure to be expected about 17,200 million Report on AJR Board Meeting DM. The work would probably not be completed by the end of 1962 as visualised in the Law. ^^ore than 60 board members, including dele liabilities would become greater, especially in view The " Council" has proposed several improve gates from the provinces, attended the AJR Board of the expansion of the work for the new homes ments of the BEG which should be incorporated meeting which was held in London on January to be established. As a further and very important into a final law on indemnification (Wiedergut- ^2nd. The comprehensive reports and the vivid device of reducing the deficit, the AJR Charitable machungs-SchlussgesetzX, the enactment of which discussion reaffirmed the variety of important tasks Trust has been established which can accept pay was intended by the German authorities but would ".* AJR and its associated bodies have to cope ments under covenant from which the charitable probably be held over until after the election of With and the organisational strength on which part of the AJR's activities are to be financed. -

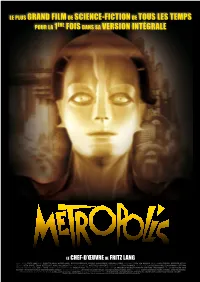

Dp-Metropolis-Version-Longue.Pdf

LE PLUS GRAND FILM DE SCIENCE-FICTION DE TOUS LES TEMPS POUR LA 1ÈRE FOIS DANS SA VERSION INTÉGRALE LE CHEf-d’œuvrE DE FRITZ LANG UN FILM DE FRITZ LANG AVEC BRIGITTE HELM, ALFRED ABEL, GUSTAV FRÖHLICH, RUDOLF KLEIN-ROGGE, HEINRICH GORGE SCÉNARIO THEA VON HARBOU PHOTO KARL FREUND, GÜNTHER RITTAU DÉCORS OTTO HUNTE, ERICH KETTELHUT, KARL VOLLBRECHT MUSIQUE ORIGINALE GOTTFRIED HUPPERTZ PRODUIT PAR ERICH POMMER. UN FILM DE LA FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG EN COOPÉRATION AVEC ZDF ET ARTE. VENTES INTERNATIONALES TRANSIT FILM. RESTAURATION EFFECTUÉE PAR LA FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG, WIESBADEN AVEC LA DEUTSCHE KINE MATHEK – MUSEUM FÜR FILM UND FERNSEHEN, BERLIN EN COOPÉRATION AVEC LE MUSEO DEL CINE PABLO C. DUCROS HICKEN, BUENOS AIRES. ÉDITORIAL MARTIN KOERBER, FRANK STROBEL, ANKE WILKENING. RESTAURATION DIGITAle de l’imAGE ALPHA-OMEGA DIGITAL, MÜNCHEN. MUSIQUE INTERPRÉTÉE PAR LE RUNDFUNK-SINFONIEORCHESTER BERLIN. ORCHESTRE CONDUIT PAR FRANK STROBEL. © METROPOLIS, FRITZ LANG, 1927 © FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG / SCULPTURE DU ROBOT MARIA PAR WALTER SCHULZE-MITTENDORFF © BERTINA SCHULZE-MITTENDORFF MK2 et TRANSIT FILMS présentent LE CHEF-D’œuvre DE FRITZ LANG LE PLUS GRAND FILM DE SCIENCE-FICTION DE TOUS LES TEMPS POUR LA PREMIERE FOIS DANS SA VERSION INTEGRALE Inscrit au registre Mémoire du Monde de l’Unesco 150 minutes (durée d’origine) - format 1.37 - son Dolby SR - noir et blanc - Allemagne - 1927 SORTIE EN SALLES LE 19 OCTOBRE 2011 Distribution Presse MK2 Diffusion Monica Donati et Anne-Charlotte Gilard 55 rue Traversière 55 rue Traversière 75012 Paris 75012 Paris [email protected] [email protected] Tél. : 01 44 67 30 80 Tél. -

Metropolis DVD Study Edition

Metropolis DVD Study Edition Film institute | DVD as a medium for critical film editions 2 Table of Contents Preface | Heinz Emigholz 3 Preface | Hortensia Völckers 4 Preface | Friedemann Beyer 5 DVD: Old films, new readings | Enno Patalas 6 Edition of a torso | Anna Bohn 8 Le tableau disparu | Björn Speidel 12 Navigare necesse est | Gunter Krüger 15 Navigation-Model 18 New Tower Metropolis | Enno Patalas 20 Making the invisible “visible” | Franziska Latell & Antje Michna 23 Metropolis, 1927 | Gottfried Huppertz 26 Metropolis, 2005 | Mark Pogolski & Aljioscha Zimmermann 27 Metropolis – Synopsis 28 Film Specifications 29 Contributors 30 Imprint 33 Thanks 35 3 Preface Many versions and editions exist of the film Metropolis, dating back to its very first screening in 1927. Commercial distribution practice at the time of the premiere cut films after their initial screening and recompiled them according to real or imaginary demands. Even the technical requirements for production of different language versions of the film raise the question just which “original” is to be protected or reconstructed. In other fields of the arts the stature and authority that even a scratched original exudes is not given in the “history of film”. There may be many of the kind, and gene- rations of copies make only for a cluster of “originals”. Reconstruction work is therefore essentially also the perception of a com- plex and viable happening only to be understood in terms of a timeline – linear and simultaneous at one and the same time. The consumer’s wish for a re-constructible film history following regular channels and self-con- tained units cannot, by its very nature, be satisfied; it is, quite simply, not logically possible. -

Gramophone, Film, Typewriter

EDITORS Timothy Lenoir and Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht GRAMOPHONE, FILM, TYPEWRITER FRIEDRICH A. KITTLER Translated, with an Introduction, by GEOFFREY WINT HROP-YOUNG AND MICHAEL WUTZ STANFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS STANFORD, CALIFORNIA The publication of this work was assisted by a subsidy from Inter Nationes, Bonn Gramophone, Film, Typewriter was originally published in German in I986 as Grammophon Film Typewriter, © I986 Brinkmann & Bose, Berlin Stanford University Press Stanford, California © I999 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University Printed in the United States of America erp data appear at the end of the book TRANSLATORS' ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A translation by Dorothea von Mucke of Kittler's Introduction was first published in October 41 (1987): 101-18. The decision to produce our own version does not imply any criticism of the October translation (which was of great help to us) but merely reflects our decision to bring the Introduction in line with the bulk of the book to produce a stylisti cally coherent text. All translations of the primary texts interpolated by Kittler are our own, with the exception of the following: Rilke, "Primal Sound," has been reprinted from Rainer Maria Rilke, Selected Works, vol. I, Prose, trans. G. Craig Houston (New York: New Directions, 1961), 51-56. © 1961 by New Directions Publishing Corporation; used with permis sion. The translation of Heidegger's lecture on the typewriter originally appeared in Martin Heidegger, Parmenides, trans. Andre Schuwer and Richard Rojcewicz (Bloomington: Indiana Univ. Press, 1992), 80-81, 85-8 6. We would like to acknowledge the help we have received from June K. -

The Proto-Filmic Monstrosity of Late Victorian Literary Figures

Bamberger Studien zu Literatur, 14 Kultur und Medien “Like some damned Juggernaut” The proto-filmic monstrosity of late Victorian literary figures Johannes Weber 14 Bamberger Studien zu Literatur, Kultur und Medien Bamberger Studien zu Literatur, Kultur und Medien hg. von Andrea Bartl, Hans-Peter Ecker, Jörn Glasenapp, Iris Hermann, Christoph Houswitschka, Friedhelm Marx Band 14 2015 “Like some damned Juggernaut” The proto-filmic monstrosity of late Victorian literary figures Johannes Weber 2015 Bibliographische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliographie; detaillierte bibliographische Informationen sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de/ abrufbar. Diese Arbeit hat der Fakultät Geistes- und Kulturwissenschaften der Otto-Friedrich- Universität Bamberg als Dissertation vorgelegen. 1. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Christoph Houswitschka 2. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Jörn Glasenapp Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 28. Januar 2015 Dieses Werk ist als freie Onlineversion über den Hochschulschriften-Server (OPUS; http://www.opus-bayern.de/uni-bamberg/) der Universitätsbibliothek Bamberg erreichbar. Kopien und Ausdrucke dürfen nur zum privaten und sons- tigen eigenen Gebrauch angefertigt werden. Herstellung und Druck: Docupoint, Magdeburg Umschlaggestaltung: University of Bamberg Press, Anna Hitthaler Umschlagbild: Screenshot aus Vampyr (1932) © University of Bamberg Press Bamberg 2015 http://www.uni-bamberg.de/ubp/ ISSN: 2192-7901 ISBN: 978-3-86309-348-8 (Druckausgabe) eISBN: 978-3-86309-349-5 (Online-Ausgabe) URN: urn:nbn:de:bvb:473-opus4-267683 Danksagung Mein besonderer Dank gilt meinem Bruder Christian für seinen fachkundigen Rat und die tatkräftige Unterstützung in allen Phasen dieser Arbeit. Ich danke meinem Doktorvater Prof. Dr. Christoph Houswitschka für viele wichtige Denkanstöße und Freiräume. -

The Concise Cinegraph

The Concise CineGraph Film Europa: German Cinema in an International Context Series Editors: Hans-Michael Bock (CineGraph Hamburg); Tim Bergfelder (University of Southampton); Sabine Hake (University of Texas, Austin) German cinema is normally seen as a distinct form, but this new series emphasizes connections, influences, and exchanges of German cinema across national borders, as well as its links with other media and art forms. Individual titles present traditional historical research (archival work, industry studies) as well as new critical approaches in film and media studies (theories of the transnational), with a special emphasis on the continuities associated with popular traditions and local perspectives. The Concise CineGraph: Encyclopaedia of German Cinema General Editor: Hans-Michael Bock Associate Editor: Tim Bergfelder International Adventures: German Popular Cinema and European Co-Productions in the 1960s Tim Bergfelder Between Two Worlds: The Jewish Presence in German and Austrian Film, 1910–1933 S. S. Prawer Framing the Fifties: Cinema in a Divided Germany Edited by John Davidson and Sabine Hake A Foreign Affair: Billy Wilder’s American Films Gerd Gemünden Destination London: German-speaking Emigrés and British Cinema, 1925–1950 Edited by Tim Bergfelder and Christian Cargnelli Michael Haneke’s Cinema: The Ethic of the Image Catherine Wheatley Willing Seduction: The Blue Angel, Marlene Dietrich, and Mass Culture Barbara Kosta Dismantling the Dream Factory: Gender, German Cinema, and the Postwar Quest for a New Film Language Hester Baer Béla Balázs’ Early Film Theory: Visible Man and The Spirit of Film Béla Balázs Translated by Rodney Livingstone Introduction by Erica Carter THE CONCISE CINEGRAPH Encyclopaedia of German Cinema General Editor: Hans-Michael Bock Associate Editor: Tim Bergfelder With a Foreword by Kevin Brownlow Published in 2009 by Berghahn Books www.berghahnbooks.com ©2009 Hans-Michael Bock Appendix: ©2009 Tim Bergfelder Die Herausgabe dieses Werkes wurde aus Mitteln des Goethe-Instituts gefördert. -

Tim Bergfelder

Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION: GERMAN-SPEAKING EMIGRÉS AND BRITISH CINEMA, 1925–50: CULTURAL EXCHANGE, EXILE AND THE BOUNDARIES OF NATIONAL CINEMA Tim Bergfelder Britain can be considered, with the possible exception of the Netherlands, the European country benefiting most from the diaspora of continental film personnel that resulted from the Nazis’ rise to power.1 Kevin Gough- Yates, who pioneered the study of exiles in British cinema, argues that ‘when we consider the films of the 1930s, in which the Europeans played a lesser role, the list of important films is small.’2 Yet the legacy of these Europeans, including their contribution to aesthetic trends, production methods, to professional training and to technological development in the film industry of their host country has been largely forgotten. With the exception of very few individuals, including the screenwriter Emeric Pressburger3 and the producer/director Alexander Korda,4 the history of émigrés in the British film industry from the 1920s through to the end of the Second World War and beyond remains unwritten. This introductory chapter aims to map some of the reasons for this neglect, while also pointing towards the new interventions on the subject that are collected in this anthology. There are complex reasons why the various waves of migrations of German-speaking artists to Britain, from the mid-1920s through to the postwar period, have not received much attention. The first has to do with the dominance of Hollywood in film historical accounts, which has given prominence to the -

SFSFF 2018 Program Book

elcome to the San Francisco Silent Film Festival for five days and nights of live cinema! This is SFSFFʼs twenty-third year of sharing revered silent-era Wmasterpieces and newly revived discoveries as they were meant to be experienced—with live musical accompaniment. We’ve even added a day, so there’s more to enjoy of the silent-era’s treasures, including features from nine countries and inventive experiments from cinema’s early days and the height of the avant-garde. A nonprofit organization, SFSFF is committed to educating the public about silent-era cinema as a valuable historical and cultural record as well as an art form with enduring relevance. In a remarkably short time after the birth of moving pictures, filmmakers developed all the techniques that make cinema the powerful medium it is today— everything except for the ability to marry sound to the film print. Yet these films can be breathtakingly modern. They have influenced every subsequent generation of filmmakers and they continue to astonish and delight audiences a century after they were made. SFSFF also carries on silent cinemaʼs live music tradition, screening these films with accompaniment by the worldʼs foremost practitioners of putting live sound to the picture. Showcasing silent-era titles, often in restored or preserved prints, SFSFF has long supported film preservation through the Silent Film Festival Preservation Fund. In addition, over time, we have expanded our participation in major film restoration projects, premiering four features and some newly discovered documentary footage at this event alone. This year coincides with a milestone birthday of film scholar extraordinaire Kevin Brownlow, whom we celebrate with an onstage appearance on June 2. -

Fritz Lang Metropolis (Germania/1927, 150’)

Fritz Lang Metropolis (Germania/1927, 150’) Regia: Fritz Lang Sceneggiatura: Thea von Harbou Fotografia: Karl Freund, Günther Rittau Effetti speciali: Eugene Schüfftan Scenografia: Otto Hunte, Erich Kettelhut, Karl Vollbrecht Costumi: Aenne Willkomm Musica: Gottfried Huppertz Interpreti: Brigitte Helm (Maria), Alfred Abel (Joh Fredersen), Gustav Fröhlich (Freder), Rudolf Klein-Rogge (Rotwang), Heinrich George (Grot), Fritz Rasp (uomo magro), Theodor Loos (Josaphat), Erwin Binswanger (Georg), Olaf Storm (Jan) Produzione: Erich Pommer per UFA. Il capolavoro di Lang è ormai riconosciuto da tutti come una delle pietre miliari del cinema, indiscussa vetta della produzione dell'Espressionismo e punto di riferimento imprescindibile per il genere fantascientifico. L'opera mette in scena un mondo distopico collocato nell'allora lontano 2026, in cui le divisioni di classe sono portare all'estremo e i ricchi vivono separati dalla massa operaia sfruttata. Sinossi Nella città di Metropolis la società è divisa in due classi: un'elite oziosa che vive nei grattacieli e gli operai schiavizzati che faticano nel sottosuolo. A capo della città Joh Fredersen, che dall'alto della grande torre di Babele controlla le attività produttive. Suo figlio Freder vede casualmente emergere dalle profondità di Metropolis un gruppo di bambini poveri accompagnati da una giovane donna, Maria. Colpito dalla miseria dei ragazzi e dalla bel•lezza di Maria, Freder li segue nel sottosuolo. Qui scopre lo spazio della fabbrica e assiste a un'esplosione che uccide un gran numero di operai. Dopo un drammatico confronto con il padre, decide di scambiare la propria vita con quella di un operaio. Intanto Joh Fredersen viene a sapere di misteriosi documenti trovati nelle tasche degli operai morti. -

The Oxford History of World Cinema EDITED by GEOFFREY NOWELL-SMITH

The Oxford History of World Cinema EDITED BY GEOFFREY NOWELL-SMITH OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX2 6DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogota Buenos Aires Calcutta Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Paris Sao Paulo Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw and associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York © Oxford University Press 1996 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 1996 First published in paperback 1997 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organizations. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Data available ISBN 0-19-811257-2 ISBN 0-19-874242-8 (Pbk.) 7 9 10 8 6 Printed in Great Britain on acid-free paper by Butler & Tanner Ltd Frome and London I should like to dedicate this book to the memory of my father, who did not live to see it finished, and to my children, for their enjoyment. -

Thea Von Harbou

Thea von Harbou Also Known As: Mrs. Rudolf Klein-Rogge Lived: December 27, 1888 - July 1, 1954 Worked as: adapter, director, novelist, screenwriter, source author, theatre actress Worked In: Germany by Brigitta B. Wagner In his 1928 book on film directing and screenwriting, Russian filmmaker Vsevolod Pudovkin notes that many literary figures had difficulty adjusting to “the optically expressive form” of film (110). Thea von Harbou, one of three German screenwriters who Pudovkin singles out, stands alongside Carl Mayer as one of the most influential film figures in Weimar German cinema, which spanned the years 1919 to 1933. Including an excerpt from Harbou’s script for Spione (1928), an espionage adventure film, Pudovkin goes on to praise the novelist Harbou for her ability to work with the film medium. Indeed, it is Harbou’s awareness of the “possibilities of the camera such as shots, framing, editing, [and] intensification through visually striking details” that distinguishes her work (212). In the scene in question—one of the most visually dynamic in the film—Harbou conveys in words the sense of movement, speed, and sudden discovery surrounding a train wreck. Each shot, each significant gesture, is noted, and in this she exemplifies the way her husband and collaborator Fritz Lang once described the model screenplay: “To the last intertitle everything has to be ready before the cameras roll” (62). Despite Pudovkin’s support and her work with Lang and F. W. Murnau, Harbou had her detractors. Unlike Lang, who did not rise to prominence with several directing and screenplay credits until 1919, Harbou had been publishing popular sensationalist novels since 1910. -

Download Detailseite

Berlinale 2010 Fritz Lang Berlinale Special METROPOLIS Gala METROPOLIS METROPOLIS Deutschland 1927/2010 Darsteller Maria/ Länge 147 Min. Maschinenmensch Brigitte Helm Format HDCAM-SR Johann Schwarzweiß „Joh“ Fredersen Alfred Abel Restaurierte Fassung Freder Fredersen Gustav Fröhlich Erfinder Rotwang Rudolf Klein- Stabliste Rogge Regie Fritz Lang Der Schmale Fritz Rasp Buch Thea von Harbou, Josaphat/Joseph Theodor Loos nach ihrem Roman Nr. 11811 Erwin Biswanger Kamera Karl Freund Grot, Wärter der Günther Rittau Herzmaschine Heinrich George Kamera-Assistenz Robert Baberske Jan Olaf Storm Günther Anders Marinus Hanns Leo Reich H. O. Schulze Zeremonienmeister Heinrich Gotho Optische Spezial- Dame im Auto Margarete Lanner effekte Eugen Schüfftan Arbeiter Max Dietze Ernst Kunstmann Georg John Trick-Kamera Helmar Lerski Walter Kurt Kühle Arthur Reinhardt Konstantin Tschet Skizze: Christina Kim Schnitt Fritz Lang Erwin Vater Bauten Otto Hunte Arbeiterinnen Grete Berger Erich Kettelhut METROPOLIS Olly Boeheim Karl Vollbrecht Fritz Langs METROPOLIS kehrt nahezu in der Originalfassung auf die Kino - Ellen Frey Plastiken Walter Schulze- leinwand zurück! 83 Jahre nach der Uraufführung wird die von der Fried - Lisa Gray Mittendorff rich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung restaurierte Fassung des Stummfilm klassi - Rosa Liechtenstein Helene Weigel Kostüm Änne Willkomm kers bei der Berlinale – und vor dem Brandenburger Tor – ihre Premiere fei- Musik Gottfried Huppertz Frauen der (Kinomusik 1927) ern. Nach der Originalpartitur von Gottfried Huppertz wird die Aufführung ewigen Gärten Beatrice Garga Produzent Erich Pommer vom Rundfunk-Sinfonie orchester Berlin unter der Leitung von Dirigent Annie Hintze Produktion Universum-Film Frank Strobel begleitet. Margarete Lanner AG (Ufa), Berlin Die Verstümmelung des Monumentalfilmes hatte unmittelbar nach seiner Helen von Münchhofen Drehzeit 22.5.1925– Premiere am 10.