Deconstruction of the Sacred, Ontologies of Monstrosity: Apophatic Approaches in Late Modernist Cinema Scott D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GLAAD Media Institute Began to Track LGBTQ Characters Who Have a Disability

Studio Responsibility IndexDeadline 2021 STUDIO RESPONSIBILITY INDEX 2021 From the desk of the President & CEO, Sarah Kate Ellis In 2013, GLAAD created the Studio Responsibility Index theatrical release windows and studios are testing different (SRI) to track lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and release models and patterns. queer (LGBTQ) inclusion in major studio films and to drive We know for sure the immense power of the theatrical acceptance and meaningful LGBTQ inclusion. To date, experience. Data proves that audiences crave the return we’ve seen and felt the great impact our TV research has to theaters for that communal experience after more than had and its continued impact, driving creators and industry a year of isolation. Nielsen reports that 63 percent of executives to do more and better. After several years of Americans say they are “very or somewhat” eager to go issuing this study, progress presented itself with the release to a movie theater as soon as possible within three months of outstanding movies like Love, Simon, Blockers, and of COVID restrictions being lifted. May polling from movie Rocketman hitting big screens in recent years, and we remain ticket company Fandango found that 96% of 4,000 users hopeful with the announcements of upcoming queer-inclusive surveyed plan to see “multiple movies” in theaters this movies originally set for theatrical distribution in 2020 and summer with 87% listing “going to the movies” as the top beyond. But no one could have predicted the impact of the slot in their summer plans. And, an April poll from Morning COVID-19 global pandemic, and the ways it would uniquely Consult/The Hollywood Reporter found that over 50 percent disrupt and halt the theatrical distribution business these past of respondents would likely purchase a film ticket within a sixteen months. -

Doubles and Doubling in Tarchetti, Capuana, and De Marchi By

Uncanny Resemblances: Doubles and Doubling in Tarchetti, Capuana, and De Marchi by Christina A. Petraglia A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Italian) At the University of Wisconsin-Madison 2012 Date of oral examination: December 12, 2012 Oral examination committee: Professor Stefania Buccini, Italian Professor Ernesto Livorni (advisor), Italian Professor Grazia Menechella, Italian Professor Mario Ortiz-Robles, English Professor Patrick Rumble, Italian i Table of Contents Introduction – The (Super)natural Double in the Fantastic Fin de Siècle…………………….1 Chapter 1 – Fantastic Phantoms and Gothic Guys: Super-natural Doubles in Iginio Ugo Tarchetti’s Racconti fantastici e Fosca………………………………………………………35 Chapter 2 – Oneiric Others and Pathological (Dis)pleasures: Luigi Capuana’s Clinical Doubles in “Un caso di sonnambulismo,” “Il sogno di un musicista,” and Profumo……………………………………………………………………………………..117 Chapter 3 – “There’s someone in my head and it’s not me:” The Double Inside-out in Emilio De Marchi’s Early Novels…………………..……………………………………………...222 Conclusion – Three’s a Fantastic Crowd……………………...……………………………322 1 The (Super)natural Double in the Fantastic Fin de Siècle: The disintegration of the subject is most often underlined as a predominant trope in Italian literature of the Twentieth Century; the so-called “crisi del Novecento” surfaces in anthologies and literary histories in reference to writers such as Pascoli, D’Annunzio, Pirandello, and Svevo.1 The divided or multifarious identity stretches across the Twentieth Century from Luigi Pirandello’s unforgettable Mattia Pascal / Adriano Meis, to Ignazio Silone’s Pietro Spina / Paolo Spada, to Italo Calvino’s il visconte dimezzato; however, its precursor may be found decades before in such diverse representations of subject fissure and fusion as embodied in Iginio Ugo Tarchetti’s Giorgio, Luigi Capuana’s detective Van-Spengel, and Emilio De Marchi’s Marcello Marcelli. -

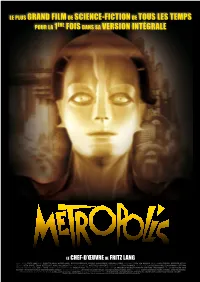

Dp-Metropolis-Version-Longue.Pdf

LE PLUS GRAND FILM DE SCIENCE-FICTION DE TOUS LES TEMPS POUR LA 1ÈRE FOIS DANS SA VERSION INTÉGRALE LE CHEf-d’œuvrE DE FRITZ LANG UN FILM DE FRITZ LANG AVEC BRIGITTE HELM, ALFRED ABEL, GUSTAV FRÖHLICH, RUDOLF KLEIN-ROGGE, HEINRICH GORGE SCÉNARIO THEA VON HARBOU PHOTO KARL FREUND, GÜNTHER RITTAU DÉCORS OTTO HUNTE, ERICH KETTELHUT, KARL VOLLBRECHT MUSIQUE ORIGINALE GOTTFRIED HUPPERTZ PRODUIT PAR ERICH POMMER. UN FILM DE LA FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG EN COOPÉRATION AVEC ZDF ET ARTE. VENTES INTERNATIONALES TRANSIT FILM. RESTAURATION EFFECTUÉE PAR LA FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG, WIESBADEN AVEC LA DEUTSCHE KINE MATHEK – MUSEUM FÜR FILM UND FERNSEHEN, BERLIN EN COOPÉRATION AVEC LE MUSEO DEL CINE PABLO C. DUCROS HICKEN, BUENOS AIRES. ÉDITORIAL MARTIN KOERBER, FRANK STROBEL, ANKE WILKENING. RESTAURATION DIGITAle de l’imAGE ALPHA-OMEGA DIGITAL, MÜNCHEN. MUSIQUE INTERPRÉTÉE PAR LE RUNDFUNK-SINFONIEORCHESTER BERLIN. ORCHESTRE CONDUIT PAR FRANK STROBEL. © METROPOLIS, FRITZ LANG, 1927 © FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG / SCULPTURE DU ROBOT MARIA PAR WALTER SCHULZE-MITTENDORFF © BERTINA SCHULZE-MITTENDORFF MK2 et TRANSIT FILMS présentent LE CHEF-D’œuvre DE FRITZ LANG LE PLUS GRAND FILM DE SCIENCE-FICTION DE TOUS LES TEMPS POUR LA PREMIERE FOIS DANS SA VERSION INTEGRALE Inscrit au registre Mémoire du Monde de l’Unesco 150 minutes (durée d’origine) - format 1.37 - son Dolby SR - noir et blanc - Allemagne - 1927 SORTIE EN SALLES LE 19 OCTOBRE 2011 Distribution Presse MK2 Diffusion Monica Donati et Anne-Charlotte Gilard 55 rue Traversière 55 rue Traversière 75012 Paris 75012 Paris [email protected] [email protected] Tél. : 01 44 67 30 80 Tél. -

Pursuing Eudaimonia LIVERPOOL HOPE UNIVERSITY STUDIES in ETHICS SERIES SERIES EDITOR: DR

Pursuing Eudaimonia LIVERPOOL HOPE UNIVERSITY STUDIES IN ETHICS SERIES SERIES EDITOR: DR. DAVID TOREVELL SERIES DEPUTY EDITOR: DR. JACQUI MILLER VOLUME ONE: ENGAGING RELIGIOUS EDUCATION Editors: Joy Schmack, Matthew Thompson and David Torevell with Camilla Cole VOLUME TWO: RESERVOIRS OF HOPE: SUSTAINING SPIRITUALITY IN SCHOOL LEADERS Author: Alan Flintham VOLUME THREE: LITERATURE AND ETHICS: FROM THE GREEN KNIGHT TO THE DARK KNIGHT Editors: Steve Brie and William T. Rossiter VOLUME FOUR: POST-CONFLICT RECONSTRUCTION Editor: Neil Ferguson VOLUME FIVE: FROM CRITIQUE TO ACTION: THE PRACTICAL ETHICS OF THE ORGANIZATIONAL WORLD Editors: David Weir and Nabil Sultan VOLUME SIX: A LIFE OF ETHICS AND PERFORMANCE Editors: John Matthews and David Torevell VOLUME SEVEN: PROFESSIONAL ETHICS: EDUCATION FOR A HUMANE SOCIETY Editors: Feng Su and Bart McGettrick VOLUME EIGHT: CATHOLIC EDUCATION: UNIVERSAL PRINCIPLES, LOCALLY APPLIED Editor: Andrew B. Morris VOLUME NINE GENDERING CHRISTIAN ETHICS Editor: Jenny Daggers VOLUME TEN PURSUING EUDAIMONIA: RE-APPROPRIATING THE GREEK PHILOSOPHICAL FOUNDATIONS OF THE CHRISTIAN APOPHATIC TRADITION Author: Brendan Cook Pursuing Eudaimonia: Re-appropriating the Greek Philosophical Foundations of the Christian Apophatic Tradition By Brendan Cook Pursuing Eudaimonia: Re-appropriating the Greek Philosophical Foundations of the Christian Apophatic Tradition, by Brendan Cook This book first published 2013 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2013 by Brendan Cook All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. -

“The Bride of Frankenstein” (1935) by Dr

Short Review: “The Bride of Frankenstein” (1935) by Dr. John L. Flynn Bride of Frankenstein, The (1935). Universal, b/w, 80 min. Director: James Whale. Producer: Carl Laemmle. Screenwriters: John Balderston and Willim Hurlbut. Cast: Boris Karloff, Colin Clive, Elsa Lanchester, Ernest Thesiger, Valerie Hobson, and Dwight Frye. The first of many Universal sequels following Whale’s classic, this was one of the few sequels that was actually superior to the original. After a brief prologue that pays homage to Mary and Percy Shelley, Lord Byron and their writing competition that inspired Frankenstein, the film picks up right where the original ended, with the monster (Karloff) dying in fire. But the monster did not die, and is soon out terrorizing the locals again. Dr. Praetorius (Thesiger) and his demented assistant Karl (Frye) pay Frankenstein (Clive) a visit, and soon the three are at work on a new creature (Lanchester). Not long after his “bride” is brought to life, the monster drops in to claim her, but she only has eyes for Frankenstein. Angered, the monster blows up the laboratory, and the usual conflagration consumes them all. “Bride” was clearly the most stylishly mounted production of the 1930's, and represents a high-water mark of the Golden Age of the American Horror Film. But it should be noted that the film title is really a misnomer and has contributed much to the confusion of the mad doctor's name with the monster. The title should have been "The Bride of the Monster of Frankenstein." Oh, well. Followed four years later by “Son of Frankenstein.” Copyright 2016 by John L. -

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

Marquetry on Drawer-Model Marionette Duo-Art

Marquetry on Drawer-Model Marionette Duo-Art This piano began life as a brown Recordo. The sound board was re-engineered, as the original ribs tapered so soon that the bass bridges pushed through. The strings were the wrong weight, and were re-scaled using computer technology. Six more wound-strings were added, and the weights of the steel strings were changed. A 14-inch Duo-Art pump, a fan-expression system, and an expression-valve-size Duo-Art stack with a soft-pedal compensation lift were all built for it. The Marquetry on the side of the piano was inspired by the pictures on the Arto-Roll boxes. The fallboard was inspired by a picture on the Rhythmodic roll box. A new bench was built, modeled after the bench originally available, but veneered to go with the rest of the piano. The AMICA BULLETIN AUTOMATIC MUSICAL INSTRUMENT COLLECTORS’ ASSOCIATION SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2005 VOLUME 42, NUMBER 5 Teresa Carreno (1853-1917) ISSN #1533-9726 THE AMICA BULLETIN AUTOMATIC MUSICAL INSTRUMENT COLLECTORS' ASSOCIATION Published by the Automatic Musical Instrument Collectors’ Association, a non-profit, tax exempt group devoted to the restoration, distribution and enjoyment of musical instruments using perforated paper music rolls and perforated music books. AMICA was founded in San Francisco, California in 1963. PROFESSOR MICHAEL A. KUKRAL, PUBLISHER, 216 MADISON BLVD., TERRE HAUTE, IN 47803-1912 -- Phone 812-238-9656, E-mail: [email protected] Visit the AMICA Web page at: http://www.amica.org Associate Editor: Mr. Larry Givens VOLUME 42, Number -

2020-2021 Bulletin

2020-2021 BULLETIN His Eminence Cardinal Blase Cupich, S.T.D. Archbishop of Chicago Chancellor Rev. Brendan Lupton, S.T.D. President Table of Contents Introduction……………….…………………………….………… 3 Mission and Objectives…………….……………………………... 3 Degree Programs…………………………….…………………… 5 Baccalaureate in Sacred Theology (S.T.B.)………….……….. 6 Admission Requirements………………………………… 6 Program Requirements………………………………….. 7 S.T.B. Core Curriculum …………………………………. 7 Topics of S.T.B. Exam ..………………………………… 8 Licentiate in Sacred Theology (S.T.L.)……..…..…………… 13 Admission Requirements….…………………………… 13 Length of Program and Residency Requirement……….. 14 Program Requirements………………………………… 15 Licentiate Thesis……………..………………………… 17 Course Descriptions…………………….……………….. 19 Reading List for S.T.L. Exam………….………………… 23 Doctorate in Sacred Theology (S.T.D.)………….....……….… 35 Admission Requirements…………………………………. 35 Program Requirements…………………………………...... 36 Dissertation ………………………………………...…..… 37 General Information Admission Policies and Procedures……...…….………..……… 40 Transfer of Credits ……..………….…………..……………… 40 Academic Integrity…………………………….……....………. 40 Grading System………………………………...……………… 41 Financial Policies …..………………………….….…………… 42 Expenses Not Covered ...………….……………………… 42 Housing on Campus……………..……………….………… 42 Administration and Faculty ……………………………..……… 43 Introduction On September 30, 1929, the Sacred Congregation of Seminaries and Universities (now known as the Congregation for Catholic Education) established a Pontifical Faculty of Theology at the University of Saint Mary of -

Cinematic Potentialities and the Student of Prague (1913) Matt Rossoni

Kino: The Western Undergraduate Journal of Film Studies Volume 4 | Issue 1 Article 9 2013 Cinematic Potentialities and The Student of Prague (1913) Matt Rossoni Keywords Student of Prague, Stellen Rye, German art film, early cinema, national cinema Recommended Citation Rossoni, Matt (2013) "Cinematic Potentialities and The Student of Prague (1913)," Kino: The Western Undergraduate Journal of Film Studies: Vol. 4 : Iss. 1 , Article 9. Rossoni: The Student of Prague Cinematic Potentialities and The Student of Prague (1913) by Matt Rossoni Stellen Rye’s 1913 release, Der Student von Prag (translated, The Student of Prague), was praised as ‘the first German art film.’ While it is always difficult to pinpoint a film as being the ‘first’ of its kind – competing closely with this particular claim is Max Mack’s short film Der Andere, also 1913 – historical circumstances were fertile for a film like The Student of Prague to emerge. At an international level, cinema was still predominantly regarded as a form of low entertainment, still caught up in its fairground origins. Debates about cinema were largely concerned with why or why it should not be considered art, especially in comparison to theatre. Artists and theorists working from both inside and outside the scope of film analysis, including, as is particularly important in the case of The Student of Prague, the burgeoning study of psychoanalysis contributed to this debate with varying attitudes, ranging from total embracement to sheer revulsion. The Student of Prague provided an important point of negotiation in such debates, attempting to win over conservative views of art while at the same time, taking a drastic step forward in terms of forming a uniquely cinematic language. -

Filip Ivanovic

C u r r i c u l u m v i t a e FILIP IVANOVIC Address: Ivana Vujosevica 19, 81000 Podgorica, Montenegro Phone: +382 69 498 468 E-mail: [email protected] EDUCATION PhD (2010-2014) Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies, Norwegian University of Science and Technology MA (2007-2009, score 110/110 cum laude) Department of Philosophy, University of Bologna BA (2004-2007, score 110/110) Department of Philosophy, University of Bologna APPOINTMENTS 2017-2018 Onassis International Fellow, Norwegian Institute at Athens 2016–2017 Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Department of Greek Studies, University of Leuven 2015-2016 Postdoctoral Research Fellow, The Polonsky Academy for Advanced Studies, The Van Leer Institute – Jerusalem 2015-2016 Visiting Researcher, Hebrew University of Jerusalem 2010-2014 Research Fellow, Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies, Norwegian University of Science and Technology – Trondheim 2010 Fellow, Centre for the Study of Antiquity and Christianity, University of Aarhus LANGUAGES Serbian (native), English (fluent), Italian (fluent), French (fluent), Spanish (reading and good communication skills), Norwegian (basic reading skills), Ancient/Byzantine Greek (reading and research skills), Modern Greek (reading and basic conversation skills) SCHOLARSHIPS AND FELLOWSHIPS 2017-2018 International Postdoctoral Fellowship, Onassis Foundation, Athens 2016–2017 Postdoctoral Research Fellowship, University of Leuven 2015-2016 Polonsky Postdoctoral Research Fellowship, The Van Leer Institute, Jerusalem 2012-2013 -

Illuminating the Darkness: the Naturalistic Evolution of Gothicism in the Nineteenth-Century British Novel and Visual Art

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English English, Department of 8-2013 Illuminating the Darkness: The Naturalistic Evolution of Gothicism in the Nineteenth-Century British Novel and Visual Art Cameron Dodworth University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Dodworth, Cameron, "Illuminating the Darkness: The Naturalistic Evolution of Gothicism in the Nineteenth- Century British Novel and Visual Art" (2013). Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English. 79. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss/79 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. ILLUMINATING THE DARKNESS: THE NATURALISTIC EVOLUTION OF GOTHICISM IN THE NINETEENTH- CENTURY BRITISH NOVEL AND VISUAL ART by Cameron Dodworth A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Major: English (Nineteenth-Century Studies) Under the Supervision of Professor Laura M. White Lincoln, Nebraska August, 2013 ILLUMINATING THE DARKNESS: THE NATURALISTIC EVOLUTION OF GOTHICISM IN THE NINETEENTH- CENTURY BRITISH NOVEL AND VISUAL ART Cameron Dodworth, Ph.D. University of Nebraska, 2013 Adviser: Laura White The British Gothic novel reached a level of very high popularity in the literary market of the late 1700s and the first two decades of the 1800s, but after that point in time the popularity of these types of publications dipped significantly. -

Classic Frenchfilm Festival

Three Colors: Blue NINTH ANNUAL ROBERT CLASSIC FRENCH FILM FESTIVAL Presented by March 10-26, 2017 Sponsored by the Jane M. & Bruce P. Robert Charitable Foundation A co-production of Cinema St. Louis and Webster University Film Series ST. LOUIS FRENCH AND FRANCOPHONE RESOURCES WANT TO SPEAK FRENCH? REFRESH YOUR FRENCH CULTURAL KNOWLEDGE? CONTACT US! This page sponsored by the Jane M. & Bruce P. Robert Charitable Foundation in support of the French groups of St. Louis. Centre Francophone at Webster University An organization dedicated to promoting Francophone culture and helping French educators. Contact info: Lionel Cuillé, Ph.D., Jane and Bruce Robert Chair in French and Francophone Studies, Webster University, 314-246-8619, [email protected], facebook.com/centrefrancophoneinstlouis, webster.edu/arts-and-sciences/affiliates-events/centre-francophone Alliance Française de St. Louis A member-supported nonprofit center engaging the St. Louis community in French language and culture. Contact info: 314-432-0734, [email protected], alliancestl.org American Association of Teachers of French The only professional association devoted exclusively to the needs of French teach- ers at all levels, with the mission of advancing the study of the French language and French-speaking literatures and cultures both in schools and in the general public. Contact info: Anna Amelung, president, Greater St. Louis Chapter, [email protected], www.frenchteachers.org Les Amis (“The Friends”) French Creole heritage preservationist group for the Mid-Mississippi River Valley. Promotes the Creole Corridor on both sides of the Mississippi River from Ca- hokia-Chester, Ill., and Ste. Genevieve-St. Louis, Mo. Parts of the Corridor are in the process of nomination for the designation of UNESCO World Heritage Site through Les Amis.