Thea Von Harbou

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Before the Forties

Before The Forties director title genre year major cast USA Browning, Tod Freaks HORROR 1932 Wallace Ford Capra, Frank Lady for a day DRAMA 1933 May Robson, Warren William Capra, Frank Mr. Smith Goes to Washington DRAMA 1939 James Stewart Chaplin, Charlie Modern Times (the tramp) COMEDY 1936 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie City Lights (the tramp) DRAMA 1931 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie Gold Rush( the tramp ) COMEDY 1925 Charlie Chaplin Dwann, Alan Heidi FAMILY 1937 Shirley Temple Fleming, Victor The Wizard of Oz MUSICAL 1939 Judy Garland Fleming, Victor Gone With the Wind EPIC 1939 Clark Gable, Vivien Leigh Ford, John Stagecoach WESTERN 1939 John Wayne Griffith, D.W. Intolerance DRAMA 1916 Mae Marsh Griffith, D.W. Birth of a Nation DRAMA 1915 Lillian Gish Hathaway, Henry Peter Ibbetson DRAMA 1935 Gary Cooper Hawks, Howard Bringing Up Baby COMEDY 1938 Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant Lloyd, Frank Mutiny on the Bounty ADVENTURE 1935 Charles Laughton, Clark Gable Lubitsch, Ernst Ninotchka COMEDY 1935 Greta Garbo, Melvin Douglas Mamoulian, Rouben Queen Christina HISTORICAL DRAMA 1933 Greta Garbo, John Gilbert McCarey, Leo Duck Soup COMEDY 1939 Marx Brothers Newmeyer, Fred Safety Last COMEDY 1923 Buster Keaton Shoedsack, Ernest The Most Dangerous Game ADVENTURE 1933 Leslie Banks, Fay Wray Shoedsack, Ernest King Kong ADVENTURE 1933 Fay Wray Stahl, John M. Imitation of Life DRAMA 1933 Claudette Colbert, Warren Williams Van Dyke, W.S. Tarzan, the Ape Man ADVENTURE 1923 Johnny Weissmuller, Maureen O'Sullivan Wood, Sam A Night at the Opera COMEDY -

Xx:2 Dr. Mabuse 1933

January 19, 2010: XX:2 DAS TESTAMENT DES DR. MABUSE/THE TESTAMENT OF DR. MABUSE 1933 (122 minutes) Directed by Fritz Lang Written by Fritz Lang and Thea von Harbou Produced by Fritz Lanz and Seymour Nebenzal Original music by Hans Erdmann Cinematography by Karl Vash and Fritz Arno Wagner Edited by Conrad von Molo and Lothar Wolff Art direction by Emil Hasler and Karll Vollbrecht Rudolf Klein-Rogge...Dr. Mabuse Gustav Diessl...Thomas Kent Rudolf Schündler...Hardy Oskar Höcker...Bredow Theo Lingen...Karetzky Camilla Spira...Juwelen-Anna Paul Henckels...Lithographraoger Otto Wernicke...Kriminalkomissar Lohmann / Commissioner Lohmann Theodor Loos...Dr. Kramm Hadrian Maria Netto...Nicolai Griforiew Paul Bernd...Erpresser / Blackmailer Henry Pleß...Bulle Adolf E. Licho...Dr. Hauser Oscar Beregi Sr....Prof. Dr. Baum (as Oscar Beregi) Wera Liessem...Lilli FRITZ LANG (5 December 1890, Vienna, Austria—2 August 1976,Beverly Hills, Los Angeles) directed 47 films, from Halbblut (Half-caste) in 1919 to Die Tausend Augen des Dr. Mabuse (The Thousand Eye of Dr. Mabuse) in 1960. Some of the others were Beyond a Reasonable Doubt (1956), The Big Heat (1953), Clash by Night (1952), Rancho Notorious (1952), Cloak and Dagger (1946), Scarlet Street (1945). The Woman in the Window (1944), Ministry of Fear (1944), Western Union (1941), The Return of Frank James (1940), Das Testament des Dr. Mabuse (The Crimes of Dr. Mabuse, Dr. Mabuse's Testament, There's a good deal of Lang material on line at the British Film The Last Will of Dr. Mabuse, 1933), M (1931), Metropolis Institute web site: http://www.bfi.org.uk/features/lang/. -

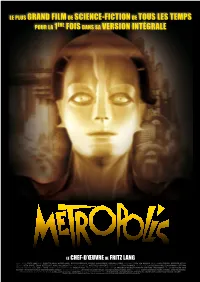

Dp-Metropolis-Version-Longue.Pdf

LE PLUS GRAND FILM DE SCIENCE-FICTION DE TOUS LES TEMPS POUR LA 1ÈRE FOIS DANS SA VERSION INTÉGRALE LE CHEf-d’œuvrE DE FRITZ LANG UN FILM DE FRITZ LANG AVEC BRIGITTE HELM, ALFRED ABEL, GUSTAV FRÖHLICH, RUDOLF KLEIN-ROGGE, HEINRICH GORGE SCÉNARIO THEA VON HARBOU PHOTO KARL FREUND, GÜNTHER RITTAU DÉCORS OTTO HUNTE, ERICH KETTELHUT, KARL VOLLBRECHT MUSIQUE ORIGINALE GOTTFRIED HUPPERTZ PRODUIT PAR ERICH POMMER. UN FILM DE LA FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG EN COOPÉRATION AVEC ZDF ET ARTE. VENTES INTERNATIONALES TRANSIT FILM. RESTAURATION EFFECTUÉE PAR LA FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG, WIESBADEN AVEC LA DEUTSCHE KINE MATHEK – MUSEUM FÜR FILM UND FERNSEHEN, BERLIN EN COOPÉRATION AVEC LE MUSEO DEL CINE PABLO C. DUCROS HICKEN, BUENOS AIRES. ÉDITORIAL MARTIN KOERBER, FRANK STROBEL, ANKE WILKENING. RESTAURATION DIGITAle de l’imAGE ALPHA-OMEGA DIGITAL, MÜNCHEN. MUSIQUE INTERPRÉTÉE PAR LE RUNDFUNK-SINFONIEORCHESTER BERLIN. ORCHESTRE CONDUIT PAR FRANK STROBEL. © METROPOLIS, FRITZ LANG, 1927 © FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG / SCULPTURE DU ROBOT MARIA PAR WALTER SCHULZE-MITTENDORFF © BERTINA SCHULZE-MITTENDORFF MK2 et TRANSIT FILMS présentent LE CHEF-D’œuvre DE FRITZ LANG LE PLUS GRAND FILM DE SCIENCE-FICTION DE TOUS LES TEMPS POUR LA PREMIERE FOIS DANS SA VERSION INTEGRALE Inscrit au registre Mémoire du Monde de l’Unesco 150 minutes (durée d’origine) - format 1.37 - son Dolby SR - noir et blanc - Allemagne - 1927 SORTIE EN SALLES LE 19 OCTOBRE 2011 Distribution Presse MK2 Diffusion Monica Donati et Anne-Charlotte Gilard 55 rue Traversière 55 rue Traversière 75012 Paris 75012 Paris [email protected] [email protected] Tél. : 01 44 67 30 80 Tél. -

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum Rivette: Texts and Interviews (editor, 1977) Orson Welles: A Critical View, by André Bazin (editor and translator, 1978) Moving Places: A Life in the Movies (1980) Film: The Front Line 1983 (1983) Midnight Movies (with J. Hoberman, 1983) Greed (1991) This Is Orson Welles, by Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich (editor, 1992) Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism (1995) Movies as Politics (1997) Another Kind of Independence: Joe Dante and the Roger Corman Class of 1970 (coedited with Bill Krohn, 1999) Dead Man (2000) Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See (2000) Abbas Kiarostami (with Mehrmax Saeed-Vafa, 2003) Movie Mutations: The Changing Face of World Cinephilia (coedited with Adrian Martin, 2003) Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Canons (2004) Discovering Orson Welles (2007) The Unquiet American: Trangressive Comedies from the U.S. (2009) Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Film Culture in Transition Jonathan Rosenbaum the university of chicago press | chicago and london Jonathan Rosenbaum wrote for many periodicals (including the Village Voice, Sight and Sound, Film Quarterly, and Film Comment) before becoming principal fi lm critic for the Chicago Reader in 1987. Since his retirement from that position in March 2008, he has maintained his own Web site and continued to write for both print and online publications. His many books include four major collections of essays: Placing Movies (California 1995), Movies as Politics (California 1997), Movie Wars (a cappella 2000), and Essential Cinema (Johns Hopkins 2004). The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2010 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. -

Close-Up on the Robot of Metropolis, Fritz Lang, 1926

Close-up on the robot of Metropolis, Fritz Lang, 1926 The robot of Metropolis The Cinémathèque's robot - Description This sculpture, exhibited in the museum of the Cinémathèque française, is a copy of the famous robot from Fritz Lang's film Metropolis, which has since disappeared. It was commissioned from Walter Schulze-Mittendorff, the sculptor of the original robot, in 1970. Presented in walking position on a wooden pedestal, the robot measures 181 x 58 x 50 cm. The artist used a mannequin as the basic support 1, sculpting the shape by sawing and reworking certain parts with wood putty. He next covered it with 'plates of a relatively flexible material (certainly cardboard) attached by nails or glue. Then, small wooden cubes, balls and strips were applied, as well as metal elements: a plate cut out for the ribcage and small springs.’2 To finish, he covered the whole with silver paint. - The automaton: costume or sculpture? The robot in the film was not an automaton but actress Brigitte Helm, wearing a costume made up of rigid pieces that she put on like parts of a suit of armour. For the reproduction, Walter Schulze-Mittendorff preferred making a rigid sculpture that would be more resistant to the risks of damage. He worked solely from memory and with photos from the film as he had made no sketches or drawings of the robot during its creation in 1926. 3 Not having to take into account the morphology or space necessary for the actress's movements, the sculptor gave the new robot a more slender figure: the head, pelvis, hips and arms are thinner than those of the original. -

Film Front Weimar: Representations of the First World War in German Films from the Weimar Period (1919-1933) Kester, Bernadette

www.ssoar.info Film Front Weimar: Representations of the First World War in German Films from the Weimar Period (1919-1933) Kester, Bernadette Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Monographie / monograph Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: OAPEN (Open Access Publishing in European Networks) Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Kester, B. (2002). Film Front Weimar: Representations of the First World War in German Films from the Weimar Period (1919-1933). (Film Culture in Transition). Amsterdam: Amsterdam Univ. Press. https://nbn-resolving.org/ urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-317059 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de * pb ‘Film Front Weimar’ 30-10-2002 14:10 Pagina 1 The Weimar Republic is widely regarded as a pre- cursor to the Nazi era and as a period in which jazz, achitecture and expressionist films all contributed to FILM FRONT WEIMAR BERNADETTE KESTER a cultural flourishing. The so-called Golden Twenties FFILMILM FILM however was also a decade in which Germany had to deal with the aftermath of the First World War. Film CULTURE CULTURE Front Weimar shows how Germany tried to reconcile IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION the horrendous experiences of the war through the war films made between 1919 and 1933. -

Gesamtkunstwerk-Film

SPIELFILMPRODUKTIONEN BENDESTORF Unterstrichene Titel sind einsehbar 1947 BIS 1952 FILMTITEL JAHR REGIE PRODUKTION DARSTELLER Menschen in Gottes Hand 1947 Rolf Meyer Junge Film-Union Paul Dahlke, Marie Angerpointner Wege im Zwielicht 1947 Gustav Fröhlich Junge Film-Union Gustav Fröhlich, Sonja Ziemann Die Söhne des Herrn Gaspary 1948 Rolf Meyer Junge Film-Union Lil Dagover, Hans Stüwe Diese Nacht vergess' ich nie 1948 Johannes Meyer Junge Film-Union Winnie Markus, Gustav Fröhlich Das Fräulein und der Vagabund 1949 Albert Benitz Junge Film-Union Eva Ingebg. Scholz, Dietmar Schönherr Der Bagnosträfling 1949 Gustav Fröhlich Junge Film-Union Paul Dahlke, Käthe Dorsch Dreizehn unter einem Hut 1949 Johannes Meyer Junge Film-Union Ruth Leuwerik, Inge Landgut Dieser Mann gehört mir 1949 Paul Verhoeven Junge Film-Union Heidemarie Hatheyer, Gustav Fröhlich Die wunderschöne Galathee 1949 Rolf Meyer Junge Film-Union Hannelore Schroth, Victor de Kowa Die Lüge 1950 Gustav Fröhlich Junge Film-Union Sybille Schmitz, Will Quadflieg Der Fall Rabanser 1950 Kurt Hoffmann Junge Film-Union Hans Söhnker, Inge Landgut Melodie des Schicksals 1950 Hans Schweikart Junge Film-Union Brigitte Horney, Victor de Kowa Taxi-Kitty 1950 Kurt Hoffmann Junge Film-Union Hannelore Schroth, Carl Raddatz Die Sünderin 1950 Willi Forst Styria-Film GmbH & Hildegard Knef, Gustav Fröhlich Junge Film-Union Professesor Nachtfalter 1950 Rolf Meyer Junge Film-Union Johannes Heesters, Maria Litto Hilfe, ich bin unsichtbar 1951 E. W. Emo Junge Film-Union Theo Lingen, Fita Benkhoff Sensation in San Remo 1951 Georg Jacoby Junge Film-Union Marika Rökk, Peter Pasetti Es geschehen noch Wunder 1951 Willi Forst Junge Film-Union Hildegard Knef, Willi Forst Die Csardasfürstin 1951 Georg Jacoby Styria-Film GmbH & Marika Rökk, Johannes Heesters Junge Film-Union Königin der Arena 1952 Rolf Meyer Corona Film Maria Litto, Hans Söhnker SPIELFILMPRODUKTIONEN BENDESTORF 1952 BIS 1959 FILMTITEL JAHR REGIE PRODUKTION DARSTELLER Der Verlorene 1951 Peter Lorre A. -

Page 1 of 3 Moma | Press | Releases | 1998 | Gallery Exhibition of Rare

MoMA | press | Releases | 1998 | Gallery Exhibition of Rare and Original Film Posters at ... Page 1 of 3 GALLERY EXHIBITION OF RARE AND ORIGINAL FILM POSTERS AT THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART SPOTLIGHTS LEGENDARY GERMAN MOVIE STUDIO Ufa Film Posters, 1918-1943 September 17, 1998-January 5, 1999 The Roy and Niuta Titus Theater 1 Lobby Exhibition Accompanied by Series of Eight Films from Golden Age of German Cinema From the Archives: Some Ufa Weimar Classics September 17-29, 1998 The Roy and Niuta Titus Theater 1 Fifty posters for films produced or distributed by Ufa, Germany's legendary movie studio, will be on display in The Museum of Modern Art's Roy and Niuta Titus Theater 1 Lobby starting September 17, 1998. Running through January 5, 1999, Ufa Film Posters, 1918-1943 will feature rare and original works, many exhibited for the first time in the United States, created to promote films from Germany's golden age of moviemaking. In conjunction with the opening of the gallery exhibition, the Museum will also present From the Archives: Some Ufa Weimar Classics, an eight-film series that includes some of the studio's more celebrated productions, September 17-29, 1998. Ufa (Universumfilm Aktien Gesellschaft), a consortium of film companies, was established in the waning days of World War I by order of the German High Command, but was privatized with the postwar establishment of the Weimar republic in 1918. Pursuing a program of aggressive expansion in Germany and throughout Europe, Ufa quickly became one of the greatest film companies in the world, with a large and spectacularly equipped studio in Babelsberg, just outside Berlin, and with foreign sales that globalized the market for German film. -

Cinematic Potentialities and the Student of Prague (1913) Matt Rossoni

Kino: The Western Undergraduate Journal of Film Studies Volume 4 | Issue 1 Article 9 2013 Cinematic Potentialities and The Student of Prague (1913) Matt Rossoni Keywords Student of Prague, Stellen Rye, German art film, early cinema, national cinema Recommended Citation Rossoni, Matt (2013) "Cinematic Potentialities and The Student of Prague (1913)," Kino: The Western Undergraduate Journal of Film Studies: Vol. 4 : Iss. 1 , Article 9. Rossoni: The Student of Prague Cinematic Potentialities and The Student of Prague (1913) by Matt Rossoni Stellen Rye’s 1913 release, Der Student von Prag (translated, The Student of Prague), was praised as ‘the first German art film.’ While it is always difficult to pinpoint a film as being the ‘first’ of its kind – competing closely with this particular claim is Max Mack’s short film Der Andere, also 1913 – historical circumstances were fertile for a film like The Student of Prague to emerge. At an international level, cinema was still predominantly regarded as a form of low entertainment, still caught up in its fairground origins. Debates about cinema were largely concerned with why or why it should not be considered art, especially in comparison to theatre. Artists and theorists working from both inside and outside the scope of film analysis, including, as is particularly important in the case of The Student of Prague, the burgeoning study of psychoanalysis contributed to this debate with varying attitudes, ranging from total embracement to sheer revulsion. The Student of Prague provided an important point of negotiation in such debates, attempting to win over conservative views of art while at the same time, taking a drastic step forward in terms of forming a uniquely cinematic language. -

The Creative Process

The Creative Process THE SEARCH FOR AN AUDIO-VISUAL LANGUAGE AND STRUCTURE SECOND EDITION by John Howard Lawson Preface by Jay Leyda dol HILL AND WANG • NEW YORK www.johnhowardlawson.com Copyright © 1964, 1967 by John Howard Lawson All rights reserved Library of Congress catalog card number: 67-26852 Manufactured in the United States of America First edition September 1964 Second edition November 1967 www.johnhowardlawson.com To the Association of Film Makers of the U.S.S.R. and all its members, whose proud traditions and present achievements have been an inspiration in the preparation of this book www.johnhowardlawson.com Preface The masters of cinema moved at a leisurely pace, enjoyed giving generalized instruction, and loved to abandon themselves to reminis cence. They made it clear that they possessed certain magical secrets of their profession, but they mentioned them evasively. Now and then they made lofty artistic pronouncements, but they showed a more sincere interest in anecdotes about scenarios that were written on a cuff during a gay supper.... This might well be a description of Hollywood during any period of its cultivated silence on the matter of film-making. Actually, it is Leningrad in 1924, described by Grigori Kozintsev in his memoirs.1 It is so seldom that we are allowed to study the disclosures of a Hollywood film-maker about his medium that I cannot recall the last instance that preceded John Howard Lawson's book. There is no dearth of books about Hollywood, but when did any other book come from there that takes such articulate pride in the art that is-or was-made there? I have never understood exactly why the makers of American films felt it necessary to hide their methods and aims under blankets of coyness and anecdotes, the one as impenetrable as the other. -

Film Posters Das Höchste Gesetz Der Natur

Filmplakate Film Posters Das höchste Gesetz der Natur Die Überlieferung zu diesem Film ist recht What we know about this film is quite sparse. dünn. Weder Regisseur noch Mitwirkende sind Neither the director nor the cast are known, bekannt, auch die nationale Produktion bzw. and even the national production and its year das Entstehungsjahr bleiben unklar. Überlie- of origin remain uncertain. What is known is fert ist jedoch ein durch die Berliner Polizei that the Berlin police issued a ban on screen- erteiltes Verbot der Aufführung vor Kindern. ings for children. In 1916 the Lichtbild-Bühne, Die „Lichtbild-Bühne“ beschreibt den Film 1916 no. f20, described the film as a dramatic Wild als dramatisches Wildwestschauspiel in drei West spectacle in three acts “that even a well- Akten, „an dem auch der wohlgesittete Euro- mannered European will enjoy.” päer sein Gefallen findet“. The only colored photograph included here, Das einzig kolorierte und damit augenfälligste and therefore the most conspicuous, shows a Foto des Plakats zeigt ein betendes Kind mit praying child with properly folded hands and artig gefalteten Händen und empor gerichteten eyes cast upwards. The woman next to the Augen. Die Frau daneben scheint jemand an- child seems to have someone else in view. The deren im Blick zu haben. Die um den Textblock smaller photos grouped around the text block gruppierten kleineren Fotos führen uns durch lead us through the plot of the film. It is the die Handlung des Films. story of two lovers whose paths have parted. Es ist die Geschichte zweier Liebender, deren A jovial third party appears, but is spurned. -

From Iron Age Myth to Idealized National Landscape: Human-Nature Relationships and Environmental Racism in Fritz Lang’S Die Nibelungen

FROM IRON AGE MYTH TO IDEALIZED NATIONAL LANDSCAPE: HUMAN-NATURE RELATIONSHIPS AND ENVIRONMENTAL RACISM IN FRITZ LANG’S DIE NIBELUNGEN Susan Power Bratton Whitworth College Abstract From the Iron Age to the modern period, authors have repeatedly restructured the ecomythology of the Siegfried saga. Fritz Lang’s Weimar lm production (released in 1924-1925) of Die Nibelungen presents an ascendant humanist Siegfried, who dom- inates over nature in his dragon slaying. Lang removes the strong family relation- ships typical of earlier versions, and portrays Siegfried as a son of the German landscape rather than of an aristocratic, human lineage. Unlike The Saga of the Volsungs, which casts the dwarf Andvari as a shape-shifting sh, and thereby indis- tinguishable from productive, living nature, both Richard Wagner and Lang create dwarves who live in subterranean or inorganic habitats, and use environmental ideals to convey anti-Semitic images, including negative contrasts between Jewish stereo- types and healthy or organic nature. Lang’s Siegfried is a technocrat, who, rather than receiving a magic sword from mystic sources, begins the lm by fashioning his own. Admired by Adolf Hitler, Die Nibelungen idealizes the material and the organic in a way that allows the modern “hero” to romanticize himself and, with- out the aid of deities, to become superhuman. Introduction As one of the great gures of Weimar German cinema, Fritz Lang directed an astonishing variety of lms, ranging from the thriller, M, to the urban critique, Metropolis. 1 Of all Lang’s silent lms, his two part interpretation of Das Nibelungenlied: Siegfried’s Tod, lmed in 1922, and Kriemhilds Rache, lmed in 1923,2 had the greatest impression on National Socialist leaders, including Adolf Hitler.