A History of Force Feeding

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prison Administrators' Authority to Force-Feed Hunger-Striking Inmates

Washington University Journal of Law & Policy Volume 23 Disabilities January 2007 What They Can Do About It: Prison Administrators' Authority to Force-Feed Hunger-Striking Inmates Tracey M. Ohm Washington University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_journal_law_policy Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Tracey M. Ohm, What They Can Do About It: Prison Administrators' Authority to Force-Feed Hunger- Striking Inmates, 23 WASH. U. J. L. & POL’Y 151 (2007), https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_journal_law_policy/vol23/iss1/6 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Journal of Law & Policy by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. What They Can Do About It: Prison Administrators’ Authority to Force-Feed Hunger-Striking Inmates * Tracey M. Ohm I. INTRODUCTION Prison inmates throughout history have employed hunger strikes as a means of opposition to authority.1 Inmates engage in hunger strikes for a variety of reasons, often in an attempt to gain leverage against prison officials2 or garner attention for the inmate’s plight or cause.3 Suicide is a motivating factor for some inmates.4 When a * J.D. Candidate (2007), Washington University in St. Louis School of Law. The author wishes to thank Professor Margo Schlanger for her guidance and expertise. 1. This Note examines hunger strikes undertaken by competent prison inmates. Analysis of hunger strikes by incompetent individuals or nonprisoners invokes different considerations. -

Scanned Image

% Jag”_I}‘_mm”ymJa_;JmJryflj___“mi IIII.II.IO-..-'I'-II.--I-.-‘II.-“~..'."...I'.U.I‘. J I #3; '--_-UlIII.I.III-.-.‘I.O".II.I.-Ill-IOUIIIII...IIIII-U-OCIII J’8 M -I.-1-|.'II.-,IIIIIIII-III-‘ll-III-I.II.lIUII.IIII..II‘l _l_O.'_U__I_._.'U.IIIII‘._OI.IlIIIIUI'I_I'..'I.I-I'UI- l-I-I-I-ll-‘I_‘I\I-UII."IC--‘II".-I..II.IOIII-...-III.II- II_.‘I.._‘_.___._____.I.'.I.‘I-I'_I.'>______II...‘_'-I__‘-I_.-'‘I'l‘_'-._I.‘I_'..-‘I.'-".......___‘.'II_-l__II_I'__ _________I-I-I‘I‘II.-I".'l‘I.--“--‘I...-...I-.'.II____.__ _____U__''_‘I-.-‘.II‘III-.l..-I."'I.-I-"-'.._._'__..I‘_____‘__"‘__.v.'-.'."7'-..‘I--...'-I-I-".'..‘..I_.“_.|.“ ________.____..._l_.'_.|._.'___I'...__"'_..III...‘-___.________-_."__."._.‘-____"____.'.'_.lI.'II ____|>_4-‘-‘_-.‘..".'__'-I-IDPII-II._"‘ .____._'|l‘_'__I_____________..._..______l...I._.._'.. ______|‘_'__.__________'_..______"...I_‘..'_’."_-...________I_____-'..."'-',I‘_.-_V..--I‘.-....-I...-'.._.-.‘...IIF-..---'__'_____________I_____________.'._"'.‘-__Il__ ‘_____I.III.I..I'-III-‘II'UIIIIII..‘l.II.I.III‘IIII______.U.-III.IIl...'I..I..-_.II‘III..IIII'.-...I--.-I‘.I.I.III..III-I_II_IO_I__I_''II‘ _-I...III..II-lIl-II.II.IIIIIII.‘I'IIIIII-III‘-" _‘IlIII_'IQIIII-‘III-I‘.IO-I.-: _OII-I..IIO.-IOII.'IIII-UI-II..._\..III'II"'IIIIIO'III‘O.‘‘I-‘I-I_I_I_UIOII‘_.lIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIO-IIIII-IQ_I-'-IIII-I-I'IIII.lIIIIIIII..lI'.-..UUIIIIIIIIUIIIIII-II.-.-.-'-I.‘."IIIII\IIU.II.lIIIO.-‘I.-III‘-I_...'II-‘II'I'I.IIIII.'.I.'IIIIO.I-.‘IIIIIII.__ I.I-I'II7-..I-II-‘I-IIIl-.II'II.‘IIIIII--..'II.lO'‘U....ll.-‘IIIII-Q-.-‘Cl_-IQIIII-IIIIIO'I’OIIII.‘......-‘|"""I'.IIIl'IOOI...-I..O-IDI-_ _____I______I'_I'D_'.I_UI_I__.llI.'_I_IIIIII'I.I9I'I.. -

Identity, Authority and Myth-Making: Politically-Motivated Prisoners and the Use of Music During the Northern Irish Conflict, 1962 - 2000

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Queen Mary Research Online Identity, authority and myth-making: Politically-motivated prisoners and the use of music during the Northern Irish conflict, 1962 - 2000 Claire Alexandra Green Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1 I, Claire Alexandra Green, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my contribution indicated. Previously published material is also acknowledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other Intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the College has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of the thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Signature: Date: 29/04/19 Details of collaboration and publications: ‘It’s All Over: Romantic Relationships, Endurance and Loyalty in the Songs of Northern Irish Politically-Motivated Prisoners’, Estudios Irlandeses, 14, 70-82. 2 Abstract. In this study I examine the use of music by and in relation to politically-motivated prisoners in Northern Ireland, from the mid-1960s until 2000. -

National Records of Scotland (NRS) Women's Suffrage Timeline

National Records of Scotland (NRS) Women’s Suffrage Timeline 1832 – First petition to parliament for women’s suffrage. FAILS Great Reform Act gives vote to more men, but no women 1866 - First mass women’s suffrage petition presented to parliament by J. S. Mill MP 1867 - First women’s suffrage societies set up. Organised campaigning begins 1870 – Women’s Suffrage Bill rejected by parliament Married Women’s Property Act gives married women the right to their own property and money 1872 – Women in Scotland given the right to vote and stand for school boards 1884 – Suffrage societies campaign for the vote through the Third Reform Act. FAILS 1894 – Local Government Act allows women to vote and stand for election at a local level 1897 – National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) formed 1903 – Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) founded by Emmeline Pankhurst 1905 – First militant action. Suffragettes interrupt a political meeting and are arrested 1906 – Liberal Party wins general election 1907 – NUWSS organises the successful ‘United Procession of Women’, the ‘Mud March’ Women’s Enfranchisement Bill reaches a second reading. FAILS Qualification of Women Act: Allows election to borough and county councils Women’s Freedom League formed 1908 – Anti-suffragist Liberal MP, Herbert Henry Asquith, becomes prime minister Women’s Sunday demonstration organised by WSPU in London. Attended by 250, 000 people from around Britain Women’s National Anti-Suffrage League (WASL) founded by Mrs Humphrey Ward 1909 - Marion Wallace-Dunlop becomes the first suffragette to hunger-strike 20 October – Adela Pankhurst, & four others interrupt a political meeting in Dundee. -

Article on Hungerstrike

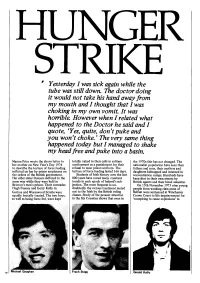

" Yesterday I was sick again while the tube was still down. The doctor doing it would not take his hand away [rom my mouth and I thought that I was choking in my own vomit. It was homble. However when I related what happened to the Doctor he said and I quote, 'Yes, quite, don'tpuke and you won't choke. ' The very same thing happened today but I managed to shake my head [ree and puke into a basin. Marian Price wrote the above letter to totaHy naked in their ceHs in solitary the 1970s this has not changed. The her mother on New Year's Day 1974 confinement as a punishment for their nationalist population have seen their to describe the torture of force feeding refusal to wear prison uniform. The fathers and sons, their mothers and inflicted on her by prison employees on torture of force feeding lasted 166 days. daughters kidnapped and interned in the orders of the British government. Students of Irish history over the last concentration camps. Hundreds have Her eIder sister Dolours suffered in the 800 years have noted many constant been shot in their own streets by same way while they were held in trends in each epoch of Ireland's sub• British agents and their hired assassins. Brixton's men's prison. Their comrades jection. The most frequent is un• On 15th November 1973 nine young Hugh Feeney and Gerry KeHy in doubtedly the vicious treatment meted people from working class areas of Gartree and Wormwood Scrubs were out to the Irish by the British ruling Belfast were sentenced at Winchester equally brutally treated. -

Northern Ireland: a Land Still Troubled by Its Past - Local & National, News - Belfasttelegr

Northern Ireland: A land still troubled by its past - Local & National, News - Belfasttelegr... Page 1 of 5 Belfast 9° Hi 9°C / Lo 2°C LOCAL & NATIONAL Search PICK THE SCORE for your chance to win £2,500 and some super prizes News Sport Business Opinion Life & Style Entertainment Jobs Cars Homes Classified LocalServices & National World Politics Property Health Education Business Environment Technology Video Family Notices Crime Map Sunday Life The CT The digital gateway to Northern Ireland news, sport, business, entertainment and opinion Home > News > Local & National Northern Ireland: A land still troubled by its past VIOLENCE RETURNS Saturday, 14 March 2009 BOOK OF CONDOLENCE Plans for military parade in Belfast halted In the week that the horror of sectarian violence Print Email PSNI quiz nine over dissident murders returned, David McKittrick asks how much Ulster has Hundreds attend vigils to show support for families really changed Search Only 300 dissidents but they are a danger: Orde Rioters pelt police after murder suspect arrests The scene at St Therese's Catholic Church in Banbridge could Republicans and unionists side by side at funeral have been an image from Northern Ireland 20 years ago. Silent Bookmark & Share Police hunt for bomb in bid to stop Real IRA attack crowds watching sombre lines of policemen marching behind the Bodies of murdered soldiers flown home coffin of a fallen comrade. Grief-stricken members of the Digg It del.icio.us Loyalist praises McGuinness but warns of ‘Real UDA’ bereaved family comforting one another as the lone piper played Thousands attend peace vigils a haunting lament. -

The Path to Revolutionary Violence Within the Weather Underground and Provisional IRA

The Path to Revolutionary Violence within the Weather Underground and Provisional IRA Edward Moran HIS 492: Seminar in History December 17, 2019 Moran 1 The 1960’s was a decade defined by a spirit of activism and advocacy for change among oppressed populations worldwide. While the methods for enacting change varied across nations and peoples, early movements such as that for civil rights in America were often committed to peaceful modes of protest and passive resistance. However, the closing years of the decade and the dawn of the 1970’s saw the patterned global spread of increasingly militant tactics used in situations of political and social unrest. The Weather Underground Organization (WUO) in America and the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA) in Ireland, two such paramilitaries, comprised young activists previously involved in the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and the Northern Irish Civil Rights Association (NICRA) respectively. What caused them to renounce the non-violent methods of the Students for a Democratic Society and the Northern Irish Civil Rights Association for the militant tactics of the Weather Underground and Irish Republican Army, respectively? An analysis of contemporary source materials, along with more recent scholarly works, reveals that violent state reactions to more passive forms of demonstration in the United States and Northern Ireland drove peaceful activists toward militancy. In the case of both the Weather Underground and the Provisional Irish Republican Army in the closing years of the 1960s and early years of the 1970s, the bulk of combatants were young people with previous experience in more peaceful campaigns for civil rights and social justice. -

Process Paper and Bibliography

ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY Primary Sources Books Kenney, Annie. Memories of a Militant. London: Edward Arnold & Co, 1924. Autobiography of Annie Kenney. Lytton, Constance, and Jane Warton. Prisons & Prisoners. London: William Heinemann, 1914. Personal experiences of Lady Constance Lytton. Pankhurst, Christabel. Unshackled. London: Hutchinson and Co (Publishers) Ltd, 1959. Autobiography of Christabel Pankhurst. Pankhurst, Emmeline. My Own Story. London: Hearst’s International Library Co, 1914. Autobiography of Emmeline Pankhurst. Newspaper Articles "Amazing Scenes in London." Western Daily Mercury (Plymouth), March 5, 1912. Window breaking in March 1912, leading to trials of Mrs. Pankhurst and Mr. & Mrs. Pethick- Lawrence. "The Argument of the Broken Pane." Votes for Women (London), February 23, 1912. The argument of the stone: speech delivered by Mrs Pankhurst on Feb 16, 1912 honoring released prisoners who had served two or three months for window-breaking demonstration in November 1911. "Attempt to Burn Theatre Royal." The Scotsman (Edinburgh), July 19, 1912. PM Asquith's visit hailed by Irish Nationalists, protested by Suffragettes; hatchet thrown into Mr. Asquith's carriage, attempt to burn Theatre Royal. "By the Vanload." Lancashire Daily Post (Preston), February 15, 1907. "Twenty shillings or fourteen days." The women's raid on Parliament on Feb 13, 1907: Christabel Pankhurst gets fourteen days and Sylvia Pankhurst gets 3 weeks in prison. "Coal That Cooks." The Suffragette (London), July 18, 1913. Thirst strikes. Attempts to escape from "Cat and Mouse" encounters. "Churchill Gives Explanation." Dundee Courier (Dundee), July 15, 1910. Winston Churchill's position on the Conciliation Bill. "The Ejection." Morning Post (London), October 24, 1906. 1 The day after the October 23rd Parliament session during which Premier Henry Campbell- Bannerman cold-shouldered WSPU, leading to protest led by Mrs Pankhurst that led to eleven arrests, including that of Mrs Pethick-Lawrence and gave impetus to the movement. -

Votes for Women (Birmingham Stories)

Votes for Women: Tracing the Struggle in Birmingham Contents Introduction: Votes For Women in Birmingham The Rise of Women’s Suffrage Societies Birmingham and the Women’s Social and Political Union Questioning The Evidence of Suffragette History in Birmingham Key Information on Suffragette Movements in Birmingham Sources from Birmingham Archives and Heritage Collections General Sources Written by Dr Andy Green, 2009. www.connectinghistories.org.uk/birminghamstories.asp Early women’s Histories in the archive Reports of the Birmingham Women’s Suffrage Society [LF 76.12] Birmingham Branch of the National Council of Women [MS 841] Women Workers Union Reports [L41.2] ‘Suffragettes at Aston Parliament’, Birmingham Weekly Mercury, 17 October 1908. Elizabeth Cadbury Papers Introduction: Votes for Women in Birmingham [MS 466] The women of Birmingham and the rest of Britain only won the right to vote through a long and difficult campaign for social equality. ‘The Representation The Female Society for of the People Bill’ (1918) allowed women over the age of thirty the chance Birmingham for the Relief to participate in national elections. Only when the ‘Equal Franchise Act’ of British Negro Slaves (1928) was introduced did all women finally have the right to take part in [IIR: 62] the parliamentary voting system as equal citizens. For centuries, a sexist opposition to women’s involvement in public life tried Birmingham Association to keep women firmly out of politics. Biological arguments that women were for the Unmarried inferior to men were underlined by sentimental portrayals of women as the Mother and Her Child rightful ‘guardians of the home’. While women from all classes, backgrounds and political opinions continued to work, challenge and support society, [MS 603] their rights were denied by a ‘patriarchal’ or ‘male centred’ British Empire in which men sought to control and dominate politics. -

Dziadok Mikalai 1'St Year Student

EUROPEAN HUMANITIES UNIVERSITY Program «World Politics and economics» Dziadok Mikalai 1'st year student Essay Written assignment Course «International relations and governances» Course instructor Andrey Stiapanau Vilnius, 2016 The Troubles (Northern Ireland conflict 1969-1998) Plan Introduction 1. General outline of a conflict. 2. Approach, theory, level of analysis (providing framework). Providing the hypothesis 3. Major actors involved, definition of their priorities, preferences and interests. 4. Origins of the conflict (historical perspective), major actions timeline 5. Models of conflicts, explanations of its reasons 6. Proving the hypothesis 7. Conclusion Bibliography Introduction Northern Ireland conflict, called “the Troubles” was the most durable conflict in the Europe since WW2. Before War in Donbass (2014-present), which lead to 9,371 death up to June 3, 20161 it also can be called the bloodiest conflict, but unfortunately The Donbass War snatched from The Troubles “the victory palm” of this dreadful competition. The importance of this issue, however, is still essential and vital because of challenges Europe experience now. Both proxy war on Donbass and recent terrorist attacks had strained significantly the political atmosphere in Europe, showing that Europe is not safe anymore. In this conditions, it is necessary for us to try to assume, how far this insecurity and tensions might go and will the circumstances and the challenges of a international relations ignite the conflict in Northern Ireland again. It also makes sense for us to recognize that the Troubles was also a proxy war to a certain degree 23 Sources, used in this essay are mostly mass-media articles, human rights observers’ and international organizations reports, and surveys made by political scientists on this issue. -

Prologue to a Biography

Notes Preface and Acknowledgements 1. R. Skidelsky, ‘Introduction’, John Maynard Keynes, Vol. 3: Fighting for Britain 1937–1946 (Macmillan Papermac, 2000), p. xxii. 1 The Caribbean in Turmoil: Prologue to a Biography 1. Lewis Archive, Princeton, Box 1/10; ‘Autobiographical Account’ by Sir Arthur Lewis, prepared for Nobel Prize Committee, December 1979, p. 4. 2. Lewis (1939), p. 5. In the 1920s, the white population in St Lucia and on average across the islands, was relatively low, at about 3 per cent of the population. The proportion was higher than this on islands completely dominated by sugar cultivation, such as Barbados. 3. Lewis (1939), p. 7. On the significance of colour gradations in the social and power structures of the West Indies, see ‘The Light and the Dark’, ch.4 in James (1963) and Tignor (2005) notes: ‘In place of the rigid two-tiered racial system, there had appeared a coloured middle class … usually light skinned, well educated, professional and urban … To this generation, Lewis … belonged’ (p.11). 4. Lewis (1939), p. 5. 5. Lewis (1939), p. 9. 6. The total value of exports from St Lucia fell from £421,000 (£8.10 per cap- ita) to £207,000 (£3.91) between 1920 and 1925, and to £143,000 (£2.65) by 1930 (Armitage-Smith, 1931, p. 62). 7. These data derive from Sir Sydney Armitage-Smith’s financial mission to the Leeward Islands and St Lucia in the depths of the depression in 1931 – undertaken while Lewis was serving time in the Agricultural Department office waiting to sit his scholarship exam. -

Secretarian Violence, Prisoner Release, and Justice Under the Good Friday Peace Accord;Note Alexander C

Journal of Legislation Volume 26 | Issue 1 Article 9 February 2015 Reconciliation of the Penitent: Secretarian Violence, Prisoner Release, and Justice under the Good Friday Peace Accord;Note Alexander C. Linn Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/jleg Recommended Citation Linn, Alexander C. (2015) "Reconciliation of the Penitent: Secretarian Violence, Prisoner Release, and Justice under the Good Friday Peace Accord;Note," Journal of Legislation: Vol. 26: Iss. 1, Article 9. Available at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/jleg/vol26/iss1/9 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Journal of Legislation at NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Legislation by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reconciliation of the Penitent: Sectarian Violence, Prisoner Release, and Justice under the Good Friday Peace Accord I. Introduction Woe to him that claims obedience when it is not due; Woe to him that refuses it when it is.' On April 10, 1998, the British and Irish governments announced agreement on a plan to end the political and military conflict in the six counties 2 of Northern Ireland. 3 If successful, the Good Friday Peace Accord ("Good Friday")4 will end the so-called 'Troubles" 5 in Northern Ireland - a conflict that has claimed over three thousand lives in the past three decades.6 The chance for success looks good: a majority of voters in the Republic of Ireland7 and in Northern Ireland recently endorsed Good Friday in popular referendums. Nevertheless, obstacles remain.