Keeping Count

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Australian Coastal Patrol

CHAPTER XI THE AUSTRALIAN COASTAL PATROL: RAIDERS AND MI NE-FI ELDS TOWARDSthe end of 1916 Australia’s part in the naval war seemed to have become almost automatic and mechanical, The Azisfralia in the North Sea, the light cruisers in the North Atlantic, the destroyers and small cruisers in East Indian waters, were engaged under various admirals in a routine of necessary though tedious duties. All that the Naval Board could do for them was to keep up a regular supply of reliefs and mails. During the year, as we have seen, the Board had considered the possibility of enemy raids into Australian seas, and made or suggested counter-prepara- tions ; but nothing had happened, and there was apparently nothing to be done outside the routine. Early in December one of the principal officers at Australian headquarters was contemplating longer week-ends merely because he was tired of sitting in his office with no intelligent occupation. But he did not contemplate them for long; nor had he ever the chance again. With the beginning of 1917, the strain of the German “ unrestricted ’’ submarine campaign was upon Australia, soon to be followed by rumours of raiders (some of them more than rumours), the discovery of mine-fields on the main coastal highway, countless reports of enemy aeroplanes (all untrue but all disturbing), and a whole series of irksome but indispensable counter-measures, ranging from patrols and mine-sweeping to wharf-guards and a drastic censorship of baggage and cargo as well as of news and private messages. During no months since the First Convov sailed was so heavy a strain put upon the brains and the mechanism of the Navy Office as during the long anxious year Of 1917. -

Book Reviews

Book Reviews Jake Alimahomed-Wilson. Solidarity Jake Alimahomed-Wilson, an aca- Forever? Race, Gender, and demic sociologist teaching at Cali- Unionism in the Ports of Southern fornia State University, Long Beach, California. Lanham, MD: Lexington uses existing repositories of oral Books, an imprint of The Rowman & histories as well as some of his own Littlefield Publishing Group, www. conducted interviews and results rowman.com, 2016. xi+205 pp., bib- from field study observation to liography, index. US $85.00, hard- explore the challenges and barriers back; ISBN 978-1-4985-1434-7. (E- facing black workers and women on book available, ISBN 978-1-4985- the waterfronts of San Pedro, Long 1435-4.) Beach, and Los Angeles at the hands of union officials and members, both The International Longshore and historically and up to the present day. Warehouse Union (ILWU), a dom- Alimahomed-Wilson argues that inant waterfront labour union along institutionalized racial and gender the West Coast of North America, inequality have been the lot of has carefully cultivated a militant, minority groups outside the over- radical image and brand that arching white, masculine longshore represents rank-and-file members and culture in the commercial ports of glorifies the long-time leadership of southern California for a long time. Harry Bridges, to almost mythical Persons of colour and women, or proportions. Oral histories — record- both, were denied fair opportunity for ed, preserved, and made available hiring and employment, consistently through the efforts of officially discriminated against and harassed, sanctioned historians like Harvey occasionally threatened with vio- Schwartz, and equally committed lence, and made to feel unwelcome individuals and groups at local levels on the waterfront. -

Annual Report 2010

ANNUAL REPORT 2010 The Europe Institute is a multi-disciplinary research institute that brings together researchers from a large number of different departments, including Accounting and Finance, Anthropology, Art History, International Business and Management, Economics, Education, European Languages and Literature, Film, Media and TV Studies, Law, and Political Studies. The mission of the Institute is to promote research, scholarship and teaching on contemporary Europe and EU-related issues, including social and economic relations, political processes, trade and investment, security, human rights, education, culture and collaboration on shared Europe-New Zealand concerns. The goals of the Institute are to: Initiate and organise a programme of research activities at The University of Auckland and in New Zealand Build and sustain our network of expertise on contemporary European issues; Initiate and coordinate new research projects; Provide support and advice for developing research programmes; Support seminars, public lectures and other events on contemporary Europe Contents Staff of the Institute ................................................................................................................................ 2 Message from the Director ..................................................................................................................... 4 Major Projects ......................................................................................................................................... 5 Summer -

(The Sea Devil), and This Wily, Handsome German Naval Officer, Count Felix Von Luckner, Lived up to the Name by Sinking Fourteen Allied Ships During World War I

His compatriots in Germany called him Der Seeteuel (the Sea Devil), and this wily, handsome German naval officer, Count Felix von Luckner, lived up to the name by sinking fourteen allied ships during World War I. His ship, the Seeadler (Sea Eagle), was the only sailing ship used by the German navy as an armed merchant ship raider. Officers under his command on the ship, as well as von Luckner and much of the crew, spoke Norwegian as well, so the three-masted sailing ship’s original name, Path of Balmaha, was changed to Seeadler, but posed as a Norwegian sailing ship with the name of Irma on its bow. With the Norwegian look and language of the ship, the vessel could easily approach a merchant ship without raising an alarm, this is until von Luckner raised the German flag and requested permission to board the merchant ship. If the request was refused, von Luckner would order a shot over the bow of the rival ship. Invariably the canon shot was enough to convince the captain of the merchant vessel to allow the German boarding crew to come aboard. All of the merchant ship’s crew was ordered off the ship and onto the Seeadler. Then von Luckner ordered his gun crews to sink the abandoned ship and its cargo. Fourteen merchant ships, plying the waters of both the Atlantic and Pacific, and carrying over 500,000 tons of cargo, were sunk by von Luckner in this manner throughout the war. Amazingly, but because of von Luckner’s method of seizing a rival ship, there was only one fatality in the sinking of the fourteen ships. -

Korv-Kptn. Felix Graf Von Luckner

Vorwort Fast 100 Jahre saß eine Unie der Grafen von Luckner auf ihrem Stammsitz, dem Schloss Altfranken westlich von Dresden. bevor dieses zu Beginn des 11.Weltkriegesabgebrochen wurde. Nach dessen Ende wurde der Adel in der sowjetischen Besatzungszone und anschließend in derODR in derZeit ihrer über 40 Jahre währenden Existenz nahezu völlig negiert. Die Geschichte der Adelsfamilien und deren territoriales Wirken wurde bewusst dem Gedächtnis der Menschen femgehalten. Nach der politischen Wende stellte ich mir deshalb die anspruchsvolle Aufgabe, auf "Spurensuche" über die Familie der Grafen von Luckner und ihren Vorfahren, zur Geschichte des Schlosses sowie über die Verwandten Grafen von Luckner vom Gutshof in Pennrich zu gehen, um die entstandene Lücke in der Heimatgeschichtezu schließen. Auf letzterem verbrachte der im I. Weltkrieg als Kaperkapitän des deutschen Kaisers Wilhelms 11. auf S.M.S. "Seeadler' so erfolgreiche "Seeteufel" ,KorvettenkapitänFelix Graf von Luckner, seine Kindheit. Nach umfangreichen Recherchen in den verschiedensten Medien sowie durch vielfältig geknüpfte Verbindungen zu Personen, Vereinen, Archiven und Museen, liegt als Ergebnis nun eine Broschüre vor, die dem Leser nicht nur Unterhaltsames und Amüsantes über die Familien der sächsischen Grafen von Luckner nahe bringt, sondern auch deren bayerische Ahnen und Persönlichkeiten der Zeitgeschichte mit erfasst, die in irgendeiner Form zu den Luckners in Beziehung standen. Besonderen Dank möchte ich all den Personen aussprechen, die mir BiId materia I zur Veröffentlichung zur Verfügung stellten und damit sehr zur Bereicherung des Inhaltes beitrugen. Werner Fritzsche Verfasser Dresden, April 2010 Die bayerischen Ahnen Ahnherr der Familie Luckner ist der Ratsherr, Stadtkämmerer, Hopfenhändler, Bierbrauer und Gastwirt Johann Jakob Luckner (1650-1707), der 1680 nach Cham (Bayern/Oberpfalz) gekommen war. -

The Islands Called Fiji

/ / / / '\ / ' / .... "' / ---.. ...... / 'I / • .::./ \ / / 4 •• • .. : ... ,.;· l z...._ ' \ u.s.s.'R. ...... ;,· ........................................ \ ·, '"' ----................. J /./l ..... I I ' .; { CHINA ..... J e Islands Call~d Fiji I I I I .,1 -;.!:1I -:d i Cl ·' Hawaiian Pacific 0 c e an Islands Mariana Islands · 0 ~ 'Guam .... -- I · Marshal I Islands :..L ..$' Caroline Island 's-.. ,o.:, .;t ';:) Gilbert Islands' ... ; :~anton Island \ \ \ \ \ .... \ \ \ \ • Samoa Islands \ -. ) I I Mopelia- I ITonga Islands 1(Friendly Islands) Cook Isl. I I AUSTRALIA I I I I I 160° W 160 °E ,y--To Sydney, Australia I / / / / / ...... / / ,:,/ / / • ... .. CANADA / '...._...._...._...._...._...._ 4 •. .... J• .:.: ... ,.,;· ............ ...._ ...... ...._ : ...._ I Men wa/ k 011 fi ery ror/;:s and wo m en Call~d Fiji sing to turtles in Britain's Paci fi c colony U.S.A. By LUIS MARDEN National Geographic Foreign Editorial Staff I I With Photographs by the Author I I .. 1 DRIFT in an open boat on the Great .51 J\ -;1 .L'\. South Sea, Lt. William Bligh, late 'l;i l commander of His Majesty's Armed Cl l I Vessel Bounty, wrote in his journal on May 3, I 1789: I I wriry intention is to Steer to the \V.N.W. I that I may see a Group of Islands called I I Hawaiian Fidgee if they lie in that direction." a 1I n Islands They did lie in that direction, and Bligh 0 c e I did sight them. \Yhat is more. the inhabitants I . I Hon6l'ulu./ of the islands called Fiji sighted him. His I ..¢ I ":~ journal for May 7 records: "We now observed two large Sailing Can noes coming swi ftly after us alongshore, and · 0 being apprehensive of their intentions we ){ rowed with some Anxiety ... -

Fanning Island

FANNING ISLAND The atoll was first discovered on 11 June 1798 by Captain Edmund Fanning, who commanded the American whaler Betsey. Fanning Island was formally annexed to Great Britain by Captain William Wiseman of HMS Caroline on 15 March 1888. The Gilbert and Ellice group of islands are in the Pacific Ocean, between 170 & 180 degrees longitude and the Gilbert Islands on the equator. When the two groups separated on 1 January 1976, the name of the Gilbert Islands, became Kiribati, and Fanning Island, reverted to its native name of Tabuaeran. Fanning Island (mid Pacific), North latitude 3.54° and 157.30° West longitude The atoll surrounds a 42.6 sq.mile lagoon with a deepest part of 50 feet and three narrow breaks inland, two for canoes, and the main entrance to English Harbour on the Western side which is 25-30 feet deep and 300 yards wide. In the 19th century, Fanning Island was exploited for guano, which was shipped to Honolulu. In 1855, Captain Henry English came with 150 natives of Manahiki Island in the Cook Islands settled and planted coconuts and exported at first coconut oil and later copra. In 1859 two vessels carried 15,000 gallons of oil to Honolulu, and in 1862 four vessels transported 44,000 gallons. By 1885 some guano was still being shipped out from Fanning and Washington, but by 1887 only copra. When the Pacific Cable Board’s station was opened at the island in 1902, the trans-Pacific mail steamers called there on the voyage from Auckland to San Francisco. -

Master Mates and Pilots January 1953

In This Issue Wage Boosts Still Huug Up in W. S. B. Capt. B. T. *Hnrst Retit'es * New Code in Effect Results of*Elections VOL. XVI JANUARY, 1953 No. 1 _ ...._------- '-----------------------* 1 Eisenhower Views the American Merchant Marine Offi. Vo B I th er m st B la tl tl tl tl o t c a i (From a policy declaration speech given in October, 1952.) t " IN 1944, from London, 1 said, 'when final victory is again will the United States neglect its merchant fleet. ours, there is no organization that will share its credit liTo assist me in the determination of policies to pro~ more deservedly than the American Merchant Marine. mote that end I have appointed Senator Saltonstall of "We were caught f1at.footed in both world wars be: Massachusetts as Chairman of a special committee of ex~ cause we relied too much upon foreign~owned and op perienced legislators to advise me on Merchant Marine erated shipping to carry our cargoes abroad and to bring problems. The other members of the committee will be critically needed supplies to this country. Congressmen Alvin Weichel of Ohio, T. Millett Hand of "America's industrial prosperity and military security New Jersey, and John Allen of California. both demand that we maintain a privately.operated mer· "This group of legislators. whose experience and in chant marine adequate in size and of modern design '1"0 terest span the entire Nation l is completely familiar with insure that our lines of supply for either peace or war will maritime affairs, and, through their advice to me, will help be safe. -

A HISTORIC SEXTANT By

A HISTORIC SEXTANT by H a rold GATTY. (Reproduced from the UNITED STATES NAVAL INSTITUTE PROCEEDINGS — Annapolis, Md., October, 1938, page 1.439.) A historic sextant made under extraordinary circumstances, the “Saginaw Sextant” was described and illustrated in the U.S. Naval Proceedings of September 1935. In the Dominion Museum at Wellington, New Zealand, there is also a very interesting sextant expertly made under most difficult conditions. So impressed was the writer by an examination of the fine workmanship of this instrument, that he was led to a further study of its history. Known as the “ Von Luckner Sextant” , it has been generally believed to be the personal handiwork of the much publicized Count, during his term of captivity in New Zealand. On close scrutiny of the sextant a faintly inscribed “W . v. Z .” indicated some other person s participation in the work. It then became necessary to retrace the story of the capture of Count von Luckner and his men in an endeavour to establish the identity of the maker of the sextant and the conditions under which it was made. The depredations of Count Felix von Luckner under the World W ar, his capture, subsequent escape, and recapture, provided one of the most interesting side-lights of the war. In command of the sea raider Seeadler he left Hamburg during Christmas week of 1916. The vessel was successful in getting through the English blockade by posing as a Norwegian sailing ship named the Irma. After seven months raiding, during which she sank 14 of the Allied merchant »hips (186,000 tons), the Seeadler was wrecked on Mopelia Island in the Society Group in August, 1917. -

The Royal Navy in New Zealand Hms Iris 1859 – 1861

THE ROYAL NAVY IN NEW ZEALAND HMS IRIS 1859 – 1861 GERALD J. ELLOTT MNZM RDP FRPSL FRPSNZ AUGUST 2017 HMS IRIS HMS Iris The name IRIS derived from “The personification of the rainbow and a favourite messenger of Zeus and Hera” Sixth Rates, 28 -24 Guns (‘Donkey Frigates’ / ‘Jackass Frigates’) Vestal Class 1831.26 Sir William Symonds design 130’,106.5’ x 40’ x 10.5’. 911 75/94 240 men, 26 guns, Keel September 1838. Launched 14 July 1840. Lent to the Atlantic Telegraph Co. in 1867, sold to Atlantic Construction & Maintenance Co. 1870. Midshipman Gambier was appointed to HMS Iris in 1857, whilst the Iris was being fitted out at Chatham, bound for the Australian Division of the East Indies Station. The following notes are taken from his memoirs’ 17 Midshipman joined at Chatham. HMS Iris sailed on 8 March 1857, however due to a gale put in at Plymouth for 24 hours, and then on to the Antipodes. Only a few days were spent at Rio de Janeiro, for two reasons, both epidemic: - Namely yellow fever and desertion from our ship, 1 The first killing people daily by the hundred. 2 The second, a disease we never shook off all the commission. The Cape was reached and whilst there Midshipman Wood fell overboard, Sydney Heads were sighted on 1 July 1857. HMS Iris, visited Norfolk Island, and visited New Zealand first in September 1857, for supplies and then back to Norfolk Island. Captain William Loring CB., was appointed the Senior Officer on the Australian Division of the East Indies Station. -

Selling Weimar German Public Diplomacy and the United States

Despite powerful war resentments, German-American relations improved rapidly after World War I. The Weimar Republic and the United States even managed to forge a strong transatlantic partnership by 1929. How did this happen? Weimar Elisabeth Piller’s groundbreaking study upends the common assumption that Weimar was incapable of selling itself abroad, illustrating instead that it pursued an innovative public diplomacy campaign engaging German Americans, U.S. universities, and Selling American tourists abroad to normalize relations and build a politically advantageous friendship with the United States. In her deeply researched, vividly illustrated history of cultural-diplomatic relations between Weimar Germany and the United States, Elisabeth Piller charts a new course in the history of transatlantic interwar diplomacy. Victoria de Grazia, Columbia University Dr. Piller has achieved a masterful synthesis of diplomatic, intellectual, and cultural history. Michael Kimmage, Catholic University of America Elisabeth Piller Winner of the Franz Steiner Prize in Transatlantic History Selling Weimar German Public Diplomacy and the United States, www.steiner-verlag.de History 1918–1933 Franz Steiner Verlag Franz Steiner Verlag Piller ISBN 978-3-515-12847-6 GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE WASHINGTON TRANSATLANTISCHE HISTORISCHE STUDIEN Publications of the German Historical Institute Washington Edited by Elisabeth Engel, Axel Jansen, Jan C. Jansen, Simone Lässig and Claudia Roesch Volume 60 The German Historical Institute Washington is a center for the advanced study of history. Since 1992, the Institute’s book series Transatlantic Historical Studies (THS) has provided a venue for research on transatlantic history and American history from early modern times to the present. Books are pub- lished in English or German. -

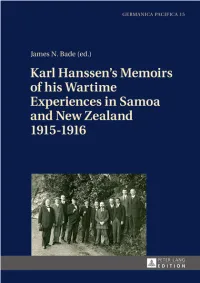

9783631667286 Intro 004.Pdf

Preface A number of people have been involved in bringing this volume to fruition� I would like to thank first and foremost Marianne Klemm of Hamburg for her support for this unique edition of Karl Hanssen’s memoirs of his time in German Samoa under New Zealand occupation and his incarceration and internment in New Zealand� Marianne Klemm, Karl Hanssen’s granddaughter, made available Karl Hanssen’s memoirs to us along with his photograph collection, and gener- ously contributed to the printing costs of this edition� I would also like to thank the Research Committee of the School of Cultures, Languages, and Linguistics for their support in contributing to the printing costs of this edition� The transcrip- tion and translation of Hanssen’s memoirs were undertaken by Faculty of Arts Summer Scholars Elizabeth Eltze and Judit Tunde McPherson in the summer of 2012–2013 and were revised by Dr James Braund in 2015� The Historical and Political Background section is based on Bronwyn Chapman’s M�A� thesis sub- mitted to the University of Auckland in March 2015 entitled “The Background to Karl Hanssen’s Great War Memoirs, 1915–1916”, which I have abridged and edited for the purposes of this edition� Professor James N� Bade Director, Research Centre for Germanic Connections with New Zealand and the Pacific University of Auckland December 2015 The Historical and Political Background to Karl Hanssen’s Memoirs Bronwyn Chapman 1. Introductory Remarks1 At the end of October 1915, as the First World War raged on the battlefields of Europe, Karl Hanssen, manager of the Deutsche Handels- und Plantagengesells- chaft (DHPG), a large copra production company, was on his way from Samoa to New Zealand aboard the SS Talune.