9783631667286 Intro 004.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Capture of the German Colonies: Samoa, Nauru

CHAPTER I1 CAPTURE OF THE GERMAN COLONIES: SAMOA, NAURU DURINGthe first phase of the naval operations the Australian Squadron had been employed on the orthodox business of fleets in war-time-searching for the enemy squadron, with the intention of bringing it to action, and, if possible, destroying it. Other business was now to be thrust upon it. On the 6th of August the British Government telegraphed the following suggestion to the Australian Government :- If your Ministers desire and feel themselves able to seize German wireless stations at Yap in Marshall Islands, Nauru 0111 Pleasant Island, and New Guinea, we should feel that this was a great and urgent Imperial service. You will, however, realise that any territory now occupied must be at the disposal of the Imperial Government for purposes of an ultimate settlement at conclusion of the war. Other Dominions are acting in similar way on the same understanding, in particular, suggestion is being made to New Zealand i7 regard to Samoa. It is now known that this proposal emanated from a sub- committee constituted on the 4th of August by the Committee of Imperial Defence, in order to consider combined naval and military operations against enemy territory. There is some evidence that the sub-committee may have assumed that, before the proposed expeditions sailed, the German Pacific Squadron would have been accounted for. When once, however, the proposals had been promulgated, that all-important conditioii was submerged, and the proposed expeditions appear to have been regarded for the time being as the primary measures of British strategy in the South Pacific. -

The Australian Coastal Patrol

CHAPTER XI THE AUSTRALIAN COASTAL PATROL: RAIDERS AND MI NE-FI ELDS TOWARDSthe end of 1916 Australia’s part in the naval war seemed to have become almost automatic and mechanical, The Azisfralia in the North Sea, the light cruisers in the North Atlantic, the destroyers and small cruisers in East Indian waters, were engaged under various admirals in a routine of necessary though tedious duties. All that the Naval Board could do for them was to keep up a regular supply of reliefs and mails. During the year, as we have seen, the Board had considered the possibility of enemy raids into Australian seas, and made or suggested counter-prepara- tions ; but nothing had happened, and there was apparently nothing to be done outside the routine. Early in December one of the principal officers at Australian headquarters was contemplating longer week-ends merely because he was tired of sitting in his office with no intelligent occupation. But he did not contemplate them for long; nor had he ever the chance again. With the beginning of 1917, the strain of the German “ unrestricted ’’ submarine campaign was upon Australia, soon to be followed by rumours of raiders (some of them more than rumours), the discovery of mine-fields on the main coastal highway, countless reports of enemy aeroplanes (all untrue but all disturbing), and a whole series of irksome but indispensable counter-measures, ranging from patrols and mine-sweeping to wharf-guards and a drastic censorship of baggage and cargo as well as of news and private messages. During no months since the First Convov sailed was so heavy a strain put upon the brains and the mechanism of the Navy Office as during the long anxious year Of 1917. -

Book Reviews

Book Reviews Jake Alimahomed-Wilson. Solidarity Jake Alimahomed-Wilson, an aca- Forever? Race, Gender, and demic sociologist teaching at Cali- Unionism in the Ports of Southern fornia State University, Long Beach, California. Lanham, MD: Lexington uses existing repositories of oral Books, an imprint of The Rowman & histories as well as some of his own Littlefield Publishing Group, www. conducted interviews and results rowman.com, 2016. xi+205 pp., bib- from field study observation to liography, index. US $85.00, hard- explore the challenges and barriers back; ISBN 978-1-4985-1434-7. (E- facing black workers and women on book available, ISBN 978-1-4985- the waterfronts of San Pedro, Long 1435-4.) Beach, and Los Angeles at the hands of union officials and members, both The International Longshore and historically and up to the present day. Warehouse Union (ILWU), a dom- Alimahomed-Wilson argues that inant waterfront labour union along institutionalized racial and gender the West Coast of North America, inequality have been the lot of has carefully cultivated a militant, minority groups outside the over- radical image and brand that arching white, masculine longshore represents rank-and-file members and culture in the commercial ports of glorifies the long-time leadership of southern California for a long time. Harry Bridges, to almost mythical Persons of colour and women, or proportions. Oral histories — record- both, were denied fair opportunity for ed, preserved, and made available hiring and employment, consistently through the efforts of officially discriminated against and harassed, sanctioned historians like Harvey occasionally threatened with vio- Schwartz, and equally committed lence, and made to feel unwelcome individuals and groups at local levels on the waterfront. -

University of Auckland Research Repository, Researchspace

Libraries and Learning Services University of Auckland Research Repository, ResearchSpace Copyright Statement The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). This thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: • Any use you make of these documents or images must be for research or private study purposes only, and you may not make them available to any other person. • Authors control the copyright of their thesis. You will recognize the author's right to be identified as the author of this thesis, and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate. • You will obtain the author's permission before publishing any material from their thesis. General copyright and disclaimer In addition to the above conditions, authors give their consent for the digital copy of their work to be used subject to the conditions specified on the Library Thesis Consent Form and Deposit Licence. Sauerkraut and Salt Water: The German-Tongan Diaspora Since 1932 Kasia Renae Cook A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in German, the University of Auckland, 2017. Abstract This is a study of individuals of German-Tongan descent living around the world. Taking as its starting point the period where Germans in Tonga (2014) left off, it examines the family histories, self-conceptions of identity, and connectedness to Germany of twenty-seven individuals living in New Zealand, the United States, Europe, and Tonga, who all have German- Tongan ancestry. -

Keeping Count

14 Keeping count Motuihe lies in the Hauraki Gulf not far from Auckland, looking from above rather like a ham bone. A long thin island spreading into lumps at each end, it is 179 hectares of subtropical paradise. It was once covered in bush and will be again, one day, when the trees being planted by an army of volunteers grow into a mature ecosystem. In the meantime it is one of the most popular islands in the Gulf. Sandy beaches grace its flanks. When the southerly wind blows the eastern side is sheltered, and in a northerly the western side remains calm, so that on any fine weekend one side of the island or the other is crammed with boats. You can float in clear, pale-green water tinted with gold and think, How wonderful, what a place to live, just above the beach there, or on that cliff, or among the trees on that gentle sunny slope. Yet this island’s history is all about people seeking to get off the island rather than onto it, and one of the strangest episodes in New Zealand’s modern history occurred here. 236 Wild Journeys_finalspp.indd 236 31/7/18 6:33 pm KEEPING COUNT Count Felix von Luckner, German raider and scourge of the South Seas in World War I, was imprisoned on Motuihe after his capture in 1917. The island became the setting for his escape, among the most daring ever seen. A few years later, von Luckner was transformed into a romantic hero, an international star. He’d won the attention of a man called Lowell Thomas, who would now be termed a creative. -

Country Coding Units

INSTITUTE Country Coding Units v11.1 - March 2021 Copyright © University of Gothenburg, V-Dem Institute All rights reserved Suggested citation: Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, Jan Teorell, and Lisa Gastaldi. 2021. ”V-Dem Country Coding Units v11.1” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. Funders: We are very grateful for our funders’ support over the years, which has made this ven- ture possible. To learn more about our funders, please visit: https://www.v-dem.net/en/about/ funders/ For questions: [email protected] 1 Contents Suggested citation: . .1 1 Notes 7 1.1 ”Country” . .7 2 Africa 9 2.1 Central Africa . .9 2.1.1 Cameroon (108) . .9 2.1.2 Central African Republic (71) . .9 2.1.3 Chad (109) . .9 2.1.4 Democratic Republic of the Congo (111) . .9 2.1.5 Equatorial Guinea (160) . .9 2.1.6 Gabon (116) . .9 2.1.7 Republic of the Congo (112) . 10 2.1.8 Sao Tome and Principe (196) . 10 2.2 East/Horn of Africa . 10 2.2.1 Burundi (69) . 10 2.2.2 Comoros (153) . 10 2.2.3 Djibouti (113) . 10 2.2.4 Eritrea (115) . 10 2.2.5 Ethiopia (38) . 10 2.2.6 Kenya (40) . 11 2.2.7 Malawi (87) . 11 2.2.8 Mauritius (180) . 11 2.2.9 Rwanda (129) . 11 2.2.10 Seychelles (199) . 11 2.2.11 Somalia (130) . 11 2.2.12 Somaliland (139) . 11 2.2.13 South Sudan (32) . 11 2.2.14 Sudan (33) . -

Annual Report 2010

ANNUAL REPORT 2010 The Europe Institute is a multi-disciplinary research institute that brings together researchers from a large number of different departments, including Accounting and Finance, Anthropology, Art History, International Business and Management, Economics, Education, European Languages and Literature, Film, Media and TV Studies, Law, and Political Studies. The mission of the Institute is to promote research, scholarship and teaching on contemporary Europe and EU-related issues, including social and economic relations, political processes, trade and investment, security, human rights, education, culture and collaboration on shared Europe-New Zealand concerns. The goals of the Institute are to: Initiate and organise a programme of research activities at The University of Auckland and in New Zealand Build and sustain our network of expertise on contemporary European issues; Initiate and coordinate new research projects; Provide support and advice for developing research programmes; Support seminars, public lectures and other events on contemporary Europe Contents Staff of the Institute ................................................................................................................................ 2 Message from the Director ..................................................................................................................... 4 Major Projects ......................................................................................................................................... 5 Summer -

German in Samoa: Historical Traces of a Colonial Variety

Poznań Studies in Contemporary Linguistics 49(3), 2013, pp. 321–353 © Faculty of English, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań, Poland doi:10.1515/psicl-2013-0012 GERMAN IN SAMOA: HISTORICAL TRACES OF A COLONIAL VARIETY DORIS STOLBERG Institut für Deutsche Sprache, Mannheim [email protected] ABSTRACT During the brief era of German colonialism in the Pacific (1884–1914), German was in contact with a large number of languages, autochthonous as well as colonial ones. This setting led to language contact in which German influenced and was influenced by vari- ous languages. In 1900, Western Samoa came under German colonial rule. The German language held a certain prestige there which is mirrored by the numbers of voluntary Samoan learners of German. On the other hand, the preferred use of English, rather than German, by native speakers of German was frequently noted. This paper examines lin- guistic and metalinguistic data that suggest the historical existence of (the precursor of) a colonial variety of German as spoken in Samoa. This variety seems to have been marked mainly by lexical borrowing from English and Samoan and was, because of these bor- rowings, not fully comprehensible to Germans who had never encountered the variety or the colonial setting in Samoa. It is discussed whether this variety can be considered a separate variety of German on linguistic grounds. KEYWORDS : Language contact; colonial linguistics; lexical borrowing; Samoan German. 1. Introduction 1 During the fairly brief era of German colonialism in the Pacific, German held a prestigious position as the native language of an exogenic economic and politi- cal elite. -

(The Sea Devil), and This Wily, Handsome German Naval Officer, Count Felix Von Luckner, Lived up to the Name by Sinking Fourteen Allied Ships During World War I

His compatriots in Germany called him Der Seeteuel (the Sea Devil), and this wily, handsome German naval officer, Count Felix von Luckner, lived up to the name by sinking fourteen allied ships during World War I. His ship, the Seeadler (Sea Eagle), was the only sailing ship used by the German navy as an armed merchant ship raider. Officers under his command on the ship, as well as von Luckner and much of the crew, spoke Norwegian as well, so the three-masted sailing ship’s original name, Path of Balmaha, was changed to Seeadler, but posed as a Norwegian sailing ship with the name of Irma on its bow. With the Norwegian look and language of the ship, the vessel could easily approach a merchant ship without raising an alarm, this is until von Luckner raised the German flag and requested permission to board the merchant ship. If the request was refused, von Luckner would order a shot over the bow of the rival ship. Invariably the canon shot was enough to convince the captain of the merchant vessel to allow the German boarding crew to come aboard. All of the merchant ship’s crew was ordered off the ship and onto the Seeadler. Then von Luckner ordered his gun crews to sink the abandoned ship and its cargo. Fourteen merchant ships, plying the waters of both the Atlantic and Pacific, and carrying over 500,000 tons of cargo, were sunk by von Luckner in this manner throughout the war. Amazingly, but because of von Luckner’s method of seizing a rival ship, there was only one fatality in the sinking of the fourteen ships. -

Korv-Kptn. Felix Graf Von Luckner

Vorwort Fast 100 Jahre saß eine Unie der Grafen von Luckner auf ihrem Stammsitz, dem Schloss Altfranken westlich von Dresden. bevor dieses zu Beginn des 11.Weltkriegesabgebrochen wurde. Nach dessen Ende wurde der Adel in der sowjetischen Besatzungszone und anschließend in derODR in derZeit ihrer über 40 Jahre währenden Existenz nahezu völlig negiert. Die Geschichte der Adelsfamilien und deren territoriales Wirken wurde bewusst dem Gedächtnis der Menschen femgehalten. Nach der politischen Wende stellte ich mir deshalb die anspruchsvolle Aufgabe, auf "Spurensuche" über die Familie der Grafen von Luckner und ihren Vorfahren, zur Geschichte des Schlosses sowie über die Verwandten Grafen von Luckner vom Gutshof in Pennrich zu gehen, um die entstandene Lücke in der Heimatgeschichtezu schließen. Auf letzterem verbrachte der im I. Weltkrieg als Kaperkapitän des deutschen Kaisers Wilhelms 11. auf S.M.S. "Seeadler' so erfolgreiche "Seeteufel" ,KorvettenkapitänFelix Graf von Luckner, seine Kindheit. Nach umfangreichen Recherchen in den verschiedensten Medien sowie durch vielfältig geknüpfte Verbindungen zu Personen, Vereinen, Archiven und Museen, liegt als Ergebnis nun eine Broschüre vor, die dem Leser nicht nur Unterhaltsames und Amüsantes über die Familien der sächsischen Grafen von Luckner nahe bringt, sondern auch deren bayerische Ahnen und Persönlichkeiten der Zeitgeschichte mit erfasst, die in irgendeiner Form zu den Luckners in Beziehung standen. Besonderen Dank möchte ich all den Personen aussprechen, die mir BiId materia I zur Veröffentlichung zur Verfügung stellten und damit sehr zur Bereicherung des Inhaltes beitrugen. Werner Fritzsche Verfasser Dresden, April 2010 Die bayerischen Ahnen Ahnherr der Familie Luckner ist der Ratsherr, Stadtkämmerer, Hopfenhändler, Bierbrauer und Gastwirt Johann Jakob Luckner (1650-1707), der 1680 nach Cham (Bayern/Oberpfalz) gekommen war. -

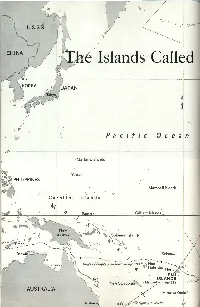

The Islands Called Fiji

/ / / / '\ / ' / .... "' / ---.. ...... / 'I / • .::./ \ / / 4 •• • .. : ... ,.;· l z...._ ' \ u.s.s.'R. ...... ;,· ........................................ \ ·, '"' ----................. J /./l ..... I I ' .; { CHINA ..... J e Islands Call~d Fiji I I I I .,1 -;.!:1I -:d i Cl ·' Hawaiian Pacific 0 c e an Islands Mariana Islands · 0 ~ 'Guam .... -- I · Marshal I Islands :..L ..$' Caroline Island 's-.. ,o.:, .;t ';:) Gilbert Islands' ... ; :~anton Island \ \ \ \ \ .... \ \ \ \ • Samoa Islands \ -. ) I I Mopelia- I ITonga Islands 1(Friendly Islands) Cook Isl. I I AUSTRALIA I I I I I 160° W 160 °E ,y--To Sydney, Australia I / / / / / ...... / / ,:,/ / / • ... .. CANADA / '...._...._...._...._...._...._ 4 •. .... J• .:.: ... ,.,;· ............ ...._ ...... ...._ : ...._ I Men wa/ k 011 fi ery ror/;:s and wo m en Call~d Fiji sing to turtles in Britain's Paci fi c colony U.S.A. By LUIS MARDEN National Geographic Foreign Editorial Staff I I With Photographs by the Author I I .. 1 DRIFT in an open boat on the Great .51 J\ -;1 .L'\. South Sea, Lt. William Bligh, late 'l;i l commander of His Majesty's Armed Cl l I Vessel Bounty, wrote in his journal on May 3, I 1789: I I wriry intention is to Steer to the \V.N.W. I that I may see a Group of Islands called I I Hawaiian Fidgee if they lie in that direction." a 1I n Islands They did lie in that direction, and Bligh 0 c e I did sight them. \Yhat is more. the inhabitants I . I Hon6l'ulu./ of the islands called Fiji sighted him. His I ..¢ I ":~ journal for May 7 records: "We now observed two large Sailing Can noes coming swi ftly after us alongshore, and · 0 being apprehensive of their intentions we ){ rowed with some Anxiety ... -

EJC Cover Page

Early Journal Content on JSTOR, Free to Anyone in the World This article is one of nearly 500,000 scholarly works digitized and made freely available to everyone in the world by JSTOR. Known as the Early Journal Content, this set of works include research articles, news, letters, and other writings published in more than 200 of the oldest leading academic journals. The works date from the mid-seventeenth to the early twentieth centuries. We encourage people to read and share the Early Journal Content openly and to tell others that this resource exists. People may post this content online or redistribute in any way for non-commercial purposes. Read more about Early Journal Content at http://about.jstor.org/participate-jstor/individuals/early- journal-content. JSTOR is a digital library of academic journals, books, and primary source objects. JSTOR helps people discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content through a powerful research and teaching platform, and preserves this content for future generations. JSTOR is part of ITHAKA, a not-for-profit organization that also includes Ithaka S+R and Portico. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. GERMANY'S LOST PACIFIC EMPIRE By the late WILLIAM CHURCHILL CHRONOLOGY 1883 Annexation by Queensland of New Guinea east of the Dutch boundary at 141? E. 1883 Annexation annulled by Great Britain. 1884 October to December. Germany annexes Kaiser-Wilhelmsland (the northern shore of New Guinea east of 141? and inland to the central ranges) for the Deutsche Neuguinea-Gesellschaft, the New Britannia Archipelago (changing its name to the Bismarck Archipelago), and the Solomon Islands as far south as the strait between Ysabel and Malaita.