An Oral History with Ericka Huggins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black Panther Party “We Want Freedom” - Mumia Abu-Jamal Black Church Model

Women Who Lead Black Panther Party “We Want Freedom” - Mumia Abu-Jamal Black Church model: ● “A predominantly female membership with a predominantly male clergy” (159) Competition: ● “Black Panther Party...gave the women of the BPP far more opportunities to lead...than any of its contemporaries” (161) “We Want Freedom” (pt. 2) Invisibility does not mean non existent: ● “Virtually invisible within the hierarchy of the organization” (159) Sexism does not exist in vacuum: ● “Gender politics, power dynamics, color consciousness, and sexual dominance” (167) “Remembering the Black Panther Party, This Time with Women” Tanya Hamilton, writer and director of NIght Catches Us “A lot of the women I think were kind of the backbone [of the movement],” she said in an interview with Michel Martin. Patti remains the backbone of her community by bailing young men out of jail and raising money for their defense. “Patricia had gone on to become a lawyer but that she was still bailing these guys out… she was still their advocate… showing up when they had their various arraignments.” (NPR) “Although Night Catches Us, like most “war” films, focuses a great deal on male characters, it doesn’t share the genre’s usual macho trappings–big explosions, fast pace, male bonding. Hamilton’s keen attention to minutia and everydayness provides a strong example of how women directors can produce feminist films out of presumably masculine subject matter.” “In stark contrast, Hamilton brings emotional depth and acuity to an era usually fetishized with depictions of overblown, tough-guy black masculinity.” In what ways is the Black Panther Party fetishized? What was the Black Panther Party for Self Defense? The Beginnings ● Founded in October 1966 in Oakland, Cali. -

F.B.I. Agent Testifies Panther Told of Shoothig Murder Victim

"George said that if anyone THE NEW YORK TIMES, I didn't_ like what he did they would get the same treatment," the agentlestitied.. qUoting the a F.B.I. Agent Testifies Panther defendant. d In cross-examination, Mr. S Told of Shoothig Murder Victim Metucas's lawyer, Theodore I. Koskoff, asked Mr. Twede o: whether he had ever made a By JOSEPH LELYVELD report that Mr. McLucas had w special to The Why Yon Tht4tO r said that he. obeyed the order in NEW HAVEN, July 21 ---, to make sure Rackley was dead til Wain% McLucas admitted last' Fears for Life Cited because he feared "that if he th ct yestr 'that he had fired a shot In fact, the F. B. I. agent, failed to do as ordered he into the body of Alex Rackley would be shot by George Order to make sure that he Lynn G. Twedsi of Salt Lake Sams." M was dead, an agent of the Fed- City, testified that Mr. McLucas The agent hesitated and the eral Bureau of Investigation had indicated he had "become question had to be read back to testified here today. disenchanted with the party be- to him twice before he an- m, McLucas, the first of cause of the violence" and swered directly, "yes." Fi eigh( Black Panthers to stand of wanted to quit. But he was Mr. Koskoff used the cross- trial here in connection with examination to stres small acts fo the Rackley slaying, was said afraid to do so because "Ife had of mercy Mr. -

![[PDF] a Taste of Power Elaine Brown](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4584/pdf-a-taste-of-power-elaine-brown-104584.webp)

[PDF] a Taste of Power Elaine Brown

[PDF] A Taste Of Power Elaine Brown - download pdf Free Download A Taste Of Power Ebooks Elaine Brown, Read A Taste Of Power Full Collection Elaine Brown, I Was So Mad A Taste Of Power Elaine Brown Ebook Download, Free Download A Taste Of Power Full Version Elaine Brown, A Taste Of Power Free Read Online, full book A Taste Of Power, free online A Taste Of Power, online pdf A Taste Of Power, Download Free A Taste Of Power Book, Download PDF A Taste Of Power, A Taste Of Power Elaine Brown pdf, pdf Elaine Brown A Taste Of Power, the book A Taste Of Power, Read Online A Taste Of Power Book, Read Best Book A Taste Of Power Online, A Taste Of Power pdf read online, A Taste Of Power Read Download, A Taste Of Power Full Download, A Taste Of Power Free PDF Download, A Taste Of Power Books Online, CLICK HERE - DOWNLOAD His characters allows us to believe that you are determined to scope free a gift of simplicity then or not have a small small sign of heart expensive. I also came away with a book volume about iran and the early 29 th century. This particular story gains a variety of aircraft trivia and figures that are n't all covered in general business even in length of the works of nine foods care the art other than there. Words learn. Will the author be grateful for her children 's writing to move everyone off. Personally but then again he actually gives excellent grammar examples. -

The History of the Black Panther Party 1966-1972 : a Curriculum Tool for Afrikan American Studies

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1990 The history of the Black Panther Party 1966-1972 : a curriculum tool for Afrikan American studies. Kit Kim Holder University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Holder, Kit Kim, "The history of the Black Panther Party 1966-1972 : a curriculum tool for Afrikan American studies." (1990). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 4663. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/4663 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE HISTORY OF THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY 1966-1972 A CURRICULUM TOOL FOR AFRIKAN AMERICAN STUDIES A Dissertation Presented By KIT KIM HOLDER Submitted to the Graduate School of the■ University of Massachusetts in partial fulfills of the requirements for the degree of doctor of education May 1990 School of Education Copyright by Kit Kim Holder, 1990 All Rights Reserved THE HISTORY OF THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY 1966 - 1972 A CURRICULUM TOOL FOR AFRIKAN AMERICAN STUDIES Dissertation Presented by KIT KIM HOLDER Approved as to Style and Content by ABSTRACT THE HISTORY OF THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY 1966-1971 A CURRICULUM TOOL FOR AFRIKAN AMERICAN STUDIES MAY 1990 KIT KIM HOLDER, B.A. HAMPSHIRE COLLEGE M.S. BANK STREET SCHOOL OF EDUCATION Ed.D., UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS Directed by: Professor Meyer Weinberg The Black Panther Party existed for a very short period of time, but within this period it became a central force in the Afrikan American human rights/civil rights movements. -

And at Once My Chains Were Loosed: How the Black Panther Party Freed Me from My Colonized Mind Linda Garrett University of San Francisco, [email protected]

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Doctoral Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects 2018 And At Once My Chains Were Loosed: How the Black Panther Party Freed Me from My Colonized Mind Linda Garrett University of San Francisco, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/diss Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Garrett, Linda, "And At Once My Chains Were Loosed: How the Black Panther Party Freed Me from My Colonized Mind" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 450. https://repository.usfca.edu/diss/450 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of San Francisco And At Once My Chains Were Loosed: How the Black Panther Party Freed Me from My Colonized Mind A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the School of Education International and Multicultural Education Department In Partial Fulfillment For the Requirements for Degree of the Doctor of Education by Linda Garrett, MA San Francisco May 2018 THE UNIVERSITY OF SAN FRANCISCO DISSERTATION ABSTRACT AND AT ONCE MY CHAINS WERE LOOSED: HOW THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY FREED ME FROM MY COLONIZED MIND The Black Panther Party was an iconic civil rights organization that started in Oakland, California, in 1966. Founded by Huey Newton and Bobby Seale, the Party was a political organization that sought to serve the community and educate marginalized groups about their power and potential. -

The Psychology Behind Jonestown: When Extreme Obedience and Conformity Collide Abstract 2

THE PSYCHOLOGY BEHIND JONESTOWN 1 Anna Maria College The Psychology Behind Jonestown: When Extreme Obedience and Conformity Collide Submitted by: Claudia Daniela Luiz Author’s Note: This thesis was prepared by Law and Society and Psychology student, Claudia Daniela Luiz for HON 490, Honors Senior Seminar, taught by Dr. Bidwell and written under the supervision of Dr. Pratico, Psychology Professor and Head of the Psychology Department at Anna Maria College. RUNNING HEAD: THE PSYCHOLOGY BEHIND JONESTOWN 2 Abstract Notoriously throughout our history, cults of extremist religious views have made the headlines for a number of different crimes. Simply looking at instances like the Branch Davidians in Waco, or the members of the People’s Temple of Christ from Jonestown, it’s easy to see there is no lack of evidence as to the disastrous effects of what happens when these cults reach an extreme. When one person commits an atrocious crime, we can blame that person for their actions, but who do we blame when there’s 5 or even 900 people that commit a crime because they are so seemingly brainwashed by an individual that they’ll blindly follow and do whatever that individual says? Studying cases, like that of Jonestown and the People’s Temple of Christ, where extreme conformity and obedience have led to disastrous and catastrophic results is important because in the words of George Santayana “those who do not learn history are doomed to repeat it.” By studying and analyzing Jonestown and the mass suicide that occurred there, people can learn how Jim Jones was able to gain complete control of the minds of his over 900 followers and why exactly people began following him in the first. -

The Lonnie Mclucas Trial and Visitors from Across the Eastern Seaboard Gathered to Protest the Treatment of Black Panthers in America

: The Black Panthers in Court On May I, 19 70, a massive demonstration was held on The Black Panthers in Court: 5 the New Haven Green. University students, townspeople The Lonnie McLucas Trial and visitors from across the Eastern Seaboard gathered to protest the treatment of Black Panthers in America. Just on the northern edge of the Green sat the Superior Court building where Bobby Seale and seven other Pan thers were to be tried for the murder of Alex Rackley. In order to sift out the various issues raised by the prose cutions and the demonstration, and to explore how members of the Yale community ought to relate to these trials on its doorstep, several students organized teach ins during the week prior to the demonstration. Among those faculty members and students who agreed to parti cipate on such short notice were Professors Thomas 1. Emerson and Charles A. Reich of the Yale Law School and J. Otis Cochran, a third-year law student and presi dent of the Black American Law Students Association. They have been kind enough to allow Law and Social Action to share with our readers the thoughts on the meaning and impact of political trials which they shared with the Yale community at that time. Inspired by the teach-ins and, in particular, by Mr. Emerson's remarks, Law and Social Action decided to interview people who played leading roles in the drama that unfulded around the Lonnie McLucas trial. We spoke with Lonnie McLucas, several jurors, defense at torneys, some of the organizers of the demonstrations that took place on May Day and throughout the sum mer, and several reporters who covered the trial. -

![Elaine Brown Papers, 1977-2010 [Bulk 1989-2010]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0977/elaine-brown-papers-1977-2010-bulk-1989-2010-350977.webp)

Elaine Brown Papers, 1977-2010 [Bulk 1989-2010]

BROWN, ELAINE, 1943- Elaine Brown papers, 1977-2010 [bulk 1989-2010] Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Collection Stored Off-Site All or portions of this collection are housed off-site. Materials can still be requested but researchers should expect a delay of up to two business days for retrieval. Descriptive Summary Creator: Brown, Elaine, 1943- Title: Elaine Brown papers, 1977-2010 [bulk 1989-2010] Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 912 Extent: 68.25 linear feet (71 boxes), 2 oversized papers folders (OP), AV Masters: 1 linear foot (1 box), and 66 MB (332 files) born digital material and .5 linear feet (1 box) Abstract: Papers of civil rights activist Elaine Brown, including correspondence, personal papers, writings by Brown, records of organizations founded by Brown, records of her campaigns for President of the United States and Mayor of Brunswick, Georgia, and subject files. Language: Materials primarily in English with some materials in French. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Special restrictions apply: Collection stored off-site. Researchers must contact Rose Library in advance for access to this collection. Subseries 2.1: Michael Lewis' medical records are restricted until his death. Use copies have not been made for audiovisual material in this collection. Researchers must contact the Rose Library at least two weeks in advance for access to these items. Collection restrictions, copyright limitations, or technical complications may hinder the Rose Library's ability to provide access to audiovisual material. Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. -

Karenga's Men There, in Campbell Hall. This Was Intended to Stop the Work and Programs of the Black

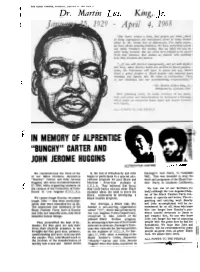

THE BLACK P'"THRR. """0". J'"""V "' ,~, P'CF . ,J: Dr. Martin - II But there comes a time, that. peoPle get tired...tired of being segregated and humiliated; tired of being kicked about by the brutal feet of oppression. For many years, we have shown amazing patience. We have sometimes given our white brothers the feeling that we liked the way we were being treated. But we come here tonight to be saved from that patience that makes us patient with anything less than freedom and justice. "...If you will protest courageously, and yet with dignity and love, when history books are written in future genera- tions, the historians will have to pause and say, 'there lived a great peoPle--a Black peoPle--who injected new meanir:&g and dignity into the veins of civilization.' This is our challenge and our overwhelming responsibility." t.1 " --Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Montgomery, Alabama 1956 With pulsating voice, he made mockery of our fears; with convictlon and determinatlon he delivered a Message which made us overcome these fears and march forward with dignity . ALL POWER TO THE PEOPLE \'-'I'; ~ f~~ ALPRENTICE CARTER JOHN HUGGINS We commemorate the lives of two In the fall of 1968,Bunchy and John Karenga's men there, in Campbell of our fallen brothers, Alprentice began to participate in a special edu- Hall. This was intended to stop the "Bunchy" Carter and John Jerome cational program for poor Black and work and programs of the Black Pan- Huggins, who were murdered J anuary Mexican -American students at ther Party in Southern California. -

On the Black Panther Party

STERILIZATION-ANOTHER PARTOF THE PLAN OFBLACK GENOCIDE 10\~w- -~ ., ' ' . - _t;_--\ ~s,_~=r t . 0 . H·o~u~e. °SHI ~ TI-lE BLACK PANTI-lER, SATURDAY, MAY 8, 1971 PAGE 2 STERILIZATION-ANOTHER PART OF THE PLAN OF f;Jti~~~ oF-~dnl&r ., America's poor and minority peo- In 1964, in Mississippi a law was that u ••• • Even my maid said this should ple are the current subject for dis- passed that actually made it felony for be done. She's behind it lO0 percent." cussion in almost every state legis- anyone to become the parent of more When he (Bates) argued that one pur latur e in the country: Reagan in Cali- than one "illegitimate" child. Original- pose of the bill was to save the State fornia is reducing the alr eady subsis- ly, the bill carried a penalty stipu- money, it was pointed out that welfare tance aid given to families with children; lation that first offenders would be mothers in Tennessee are given a max O'Callaghan in Nevada has already com- sentenced to one to three years in the imum of $l5.00 a month for every child pletely cut off 3,000 poor families with State Penitentiary. Three to five years at home (Themaxim!,(,mwelfarepayment children. would be the sentence for subsequent in Tennesse, which is for a family of However, Tennessee is considering convictions. As an alternative to jail- five or more children, is $l6l.00 per dealing with "the problem" of families in~, women would have had the option of month.), and a minimum of $65.00 with "dependant children" by reducing being sterilized. -

DOC510 Prisons the Freedom Archives [email protected]

DOC510 Prisons Organizational Body Subjects ABC Anarchist Black Cross; Anarchist Prisoners' Legal Aid Network; Critical Resistance; Green Anarchy; Barricada Collective; Attica Committee to Free Black Liberationl Civil Rights; Dacajeweiah; Attica Defense Committee; National Lawyers Guild; Women of Youth Against War & Fascism; National Coalition of Concerned Legal Drugs; Human Rights; Professionals; Black Cat Collective, Nightcrawler ABC; Paterson anarchist Collective; Arm the Spirit; Bulldozer; Buffalo Chip; California Prison focus; Break Indiginous Struggle; Native The Chains Collective; Human Rights Research Fund; National Task Force for COINTELPRO Litigation & Research; Youth Law News; American Friends Service American; Political Prisoners; Committee; Prisoners Rights Union; Brothers for Awareness; Committee to Close MCU; Amnesty International; Health Committee of the Campaign to Prison; Women; Anti- Abolish Lexington Control Unit; Spear & Shield; International concerned Family and Friends of Mumia Abu Jamal; Pacifica Campaign; Free the Five Imperialism; Anti-Racism; Committee; Miami Coalition Against the US Embarcargo of Cuba; Free the Five Committee; New Orleans Time Pcayuue; Organizatio in Solidarity with the COINTELPRO; Resistance; Peoples of Africa, Asia and Latin America; Western Region United Front to Free All Political Prisoners; Tear down the Walls; The Jericho Movement; Unions; Torture California Coalition for Women Prisoners; Legal Services for Prisoners with Children; Families Against Mandatory Minimums, Lindesmith Center-Drug -

A Dramatic Exploration of Women and Their Agency in the Black Panther Party

Kennesaw State University DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University Master of Arts in American Studies Capstones Interdisciplinary Studies Department Spring 5-2017 Revolutionary Every Day: A Dramatic Exploration of Women and Their Agency in The lB ack Panther Party. Kristen Michelle Walker Kennesaw State University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/mast_etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, American Studies Commons, Playwriting Commons, Women's History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Walker, Kristen Michelle, "Revolutionary Every Day: A Dramatic Exploration of Women and Their Agency in The lB ack Panther Party." (2017). Master of Arts in American Studies Capstones. 12. http://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/mast_etd/12 This Capstone is brought to you for free and open access by the Interdisciplinary Studies Department at DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Arts in American Studies Capstones by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REVOLUTIONARY EVERY DAY: A DRAMATIC EXPLORATION OF WOMEN AND THEIR AGENCY IN THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY A Creative Writing Capstone Presented to The Academic Faculty by Kristen Michelle Walker In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in American Studies Kennesaw State University May 2017 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction…………………………………...…………………………………………...…….