An Institution Based Insight Into India's Tea Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tea Industry

Tea Industry Introduction The Indian tea industry is nearly 200 years old. Robert Bruce, a British national discovered tea plants growing in the upper Brahmaputra valley in Assam and adjoining areas. In 1838, Indian tea that was grown in Assam was sent to the UK for the first time, for public sale. Tea in India is grown primarily in Assam, West Bengal, Tamil Nadu and Kerala. Apart from this, it is also grown in small quantities in Karnataka, HP, Tripura, Uttaranchal, Arunachal Pradesh, Manipur, Sikkim and Meghalaya. India has a dual tea base, unlike most other tea exporting countries. Both CTC and Orthodox tea is produced in India. The tea industry is agro‐based and labour intensive. It provides direct employment to over 1 million persons. Through its forward and backward linkages another 10 million persons derive their livelihood from tea. In Northeast India alone, the tea industry employs around 900,000 persons on permanent rolls. It is one of the largest employers of women amonst organized industries in India. Women constitute nearly 51% of the total workforce. The tea estates in the North Eastern India are located in industrially backward areas. Tea being the only organised industry in the private sector in this region, people outside the tea estates have high expectations from the industry. The three most distinct known varieties of tea in India are: a) Assam tea (grown in Assam and other parts of NE India) b) Darjeeling tea (grown in Darjeeling and other parts of West Bengal) c) Nilgiri tea (grown in the Nilgiri hills of Tamil Nadu) Objective Through this dissertation project, I intend to study, with respect to the CIS nations and the United Kingdom that serve as the foremost export markets, the Indian tea industry in detail, the trends observed in the past, the highs and lows of export volumes to these countries and the reasons behind them, as well as future prospects on where Indian would stand in the global arena. -

Miss Farhat Jabeen

Some Aspects of the Sociai History of the Valley of Kashmir during the period 1846—1947'-Customs and Habits By: lUEblS Miss Farhat Jabeen Thesis Submitted for the award of i Doctor of Philosophy ( PH. D.) Post Graduate Department of History THE: UNIVERSITY OF KASHAIIR ^RXNJf.GA.R -190006 T5240 Thl4 is to certify that the Ph.D. thesis of Miss Far hat JabeiA entitled "Some Aspects of the Social History of tha Valley of Kashnir during the period 1846.-1947— Cus^ms and Habits*• carried out under my supervision embodies the work of the candidate. The research vork is of original nature and has not been submlt-ted for a Ph.D. degree so far« It is also certified that the scholar has put in required I attendance in the Department of History* University of Kashmir, The thesis is in satisfactory literary form and worthy of consideration for a Ph.D. degree* SUPERVISOR '»•*•« $#^$7M7«^;i«$;i^ !• G, R, *** General Records 2. JSdC ••• Jammu and Kashmir 3, C. M, S. ••» Christian Missionary Society 4. Valley ••* The Valley of Kashmir 5. Govt. **i* Government 6, M.S/M.S.S *** ManuscriptAlenuscripts, 7. NOs Number 8, P. Page 9, Ed. ••• Edition, y-itU 10. K.T. *•• Kashmir Today 11. f.n* •••f Foot Note 12» Vol, ••• Volume 13. Rev, •*• Revised 14. ff/f **• VniiosAolio 15, Deptt. *** Department 16. ACC *** Accession 17. Tr, *** Translated 18. Blk *** Bikrand. ^v^s^s ^£!^mmmSSSmSSimSSSmS^lSSmSm^^ ACKNOWL EDGEMENTt This Study was undertaken in the year 1985) December, as a research project for ny Ph.D. programme under the able guidance of Dr. -

Rainbow Tea Company

+91-8048372706 Rainbow Tea Company https://www.indiamart.com/rainbow-tea-company/ Established in the year 2001, Rainbow Tea Company is a well- known wholesaler of Assam Tea, Black Tea, Dooars Tea, Green Tea, Loose Tea, Nilgiri Tea, Tea Leaves and much more. About Us Established in the year 2001, Rainbow Tea Company is a well-known wholesaler of Assam Tea, Black Tea, Dooars Tea, Green Tea, Loose Tea, Nilgiri Tea, Tea Leaves and much more. All these products are quality assured by the executive to ensure longer life. Highly demanded in different industries, these products are accessible from the market in different shapes, sizes and configurations. With the leadership and extreme knowledge of Mr. Onkar Nath Gupta we are maintaining our topmost position in the global market. For more information, please visit https://www.indiamart.com/rainbow-tea-company/profile.html TEA LEAVES O u r P r o d u c t R a n g e Tea Leaves Natural Tea Leaves Green Tea Leaves Fresh Green Tea Leaves ASSAM TEA O u r P r o d u c t R a n g e Assam Tea Black Assam Tea Assam Black Tea BLACK TEA O u r P r o d u c t R a n g e CTC Black Tea Black Tea Premium CTC Black Tea DOOARS TEA O u r P r o d u c t R a n g e Natural Dooars Tea Dooars Tea Fresh Dooars Tea LOOSE TEA O u r P r o d u c t R a n g e Assam Loose Tea Loose Tea Natural Loose Tea O u r OTHER PRODUCTS: P r o d u c t R a n g e Organic Green Tea Natural Green Tea Nilgiri Tea Fresh Nilgiri Tea F a c t s h e e t Year of Establishment : 2001 Nature of Business : Wholesaler Total Number of Employees : Upto 10 People CONTACT US Rainbow Tea Company Contact Person: Onkar Nath Gupta No. -

Journal 33.Pdf

1 GOVERNMENT OF INDIA GEOGRAPHICAL INDICATIONS JOURNAL NO. 33 APRIL 30, 2010 / VAISAKHA 2, SAKA 1932 2 INDEX Page S.No. Particulars No. 1. Official Notices 4 2. G.I Application Details 5 3. Public Notice 11 4. Sandur Lambani Embroidery 12 5. Hand Made Carpet of Bhadohi 31 6. Paithani Saree & Fabrics 43 7. Mahabaleshwar Strawberry 65 8. Hyderabad Haleem 71 9. General Information 77 10. Registration Process 81 3 OFFICIAL NOTICES Sub: Notice is given under Rule 41(1) of Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration & Protection) Rules, 2002. 1. As per the requirement of Rule 41(1) it is informed that the issue of Journal 33 of the Geographical Indications Journal dated 30th April 2010 / Vaisakha 2, Saka 1932 has been made available to the public from 30th April 2010. 4 G.I. Geographical Indication Class Goods App.No. 1 Darjeeling Tea (word) 30 Agricultural 2 Darjeeling Tea (Logo) 30 Agricultural 3 Aranmula Kannadi 20 Handicraft 24, 25 & 4 Pochampalli Ikat Textile 27 5 Salem Fabric 24 Textile 6 Payyannur Pavithra Ring 14 Handicraft 7 Chanderi Fabric 24 Textile 8 Solapur Chaddar 24 Textile 9 Solapur Terry Towel 24 Textile 10 Kotpad Handloom fabric 24 Textile 24, 25 & 11 Mysore Silk Textile 26 12 Kota Doria 24 & 25 Textile 13 Mysore Agarbathi 3 Manufactured 14 Basmati Rice 30 Agricultural 15 Kancheepuram Silk 24 & 25 Textile 16 Bhavani Jamakkalam 24 Textile 17 Navara - The grain of Kerala 30 Agricultural 18 Mysore Agarbathi "Logo" 3 Manufactured 19 Kullu Shawl 24 Textile 20 Bidriware 6, 21 & 34 Handicraft 21 Madurai Sungudi Saree 24 & 25 -

The Traditional Calling Card

Heritage The traditional calling card India’s cultural heritage is represented through its rich variety of indigenous products and handicrafts. As the country becomes ‘Vocal for local’, Chinnaraja Naidu takes us through the journey of GI (Geographical Indication) tags and how they help local producers to protect and promote their unique crafts and traditionally acquired knowledge in the country A man showcasing Odisha’s GI tagged Single Ikat weaving tradition that includes the Bomkai and the striped or chequered Santhali sarees Left to right: A farmer harvests saffron from flowers near Srinagar, Jammu and Kashmir. Kashmiri saffron, a GI tagged product, is valued all over the world for its fine quality; Prime Minister Narendra Modi with an indigenous Meitei Lengyan scarf of Manipuri With a demography as culturally Several of Prime Minister of India Scripting diverse as India, the gamusa is not the history Narendra Modi’s recent only unique product, in fact, it is one appearances have been amongst over 370 products exclusively The Geographical Indications Registry with with the gamusa, a produced across different regions pan-India jurisdiction was traditionally woven scarf of the country. In a mammoth effort set up in Chennai, Tamil with distinctive red borders and floral to protect, propagate and celebrate Nadu and functions under motifs from the state of Assam. The Indian culture, the Geographical the Registrar of rectangular piece of clothing has Indications (GI) were launched in Geographical Indications. The Controller General of been an iconic symbol of Assamese 2004-05 as an intellectual property culture since the 18th century. Patents, Designs, and right, belonging to the concerned Trade Marks is also the Keeping aside its cultural and community of the said goods. -

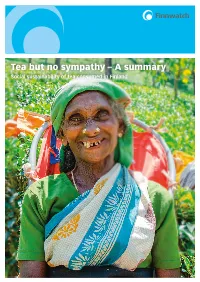

Tea but No Sympathy – a Summary

Tea but no sympathy – A summary Social sustainability of tea consumed in Finland Supported by crowdfunding organised on the People´s Cultural Foundation’s Kulttuurilahja -plat- form and by the Finnwatch Decent Work Research Programme. The Programme is supported by: An abbreviated and translated version of the original Finnish report. In the event of interpretation disputes the Finnish text applies. The original is available at www.fi nnwatch.org. Finnwatch is a non-profi t organisation that investigates the global impacts of Finnish business en- terprises. Finnwatch is supported by 11 development, environmental and consumer organisations and trade unions: The International Solidarity Foundation ISF, Finnish Development NGOs – Fingo, The Finnish Evangelical Lutheran Mission Felm, Pro Ethical Trade Finland, The Trade Union Solidarity Centre of Finland SASK, Attac, Finn Church Aid, The Dalit Solidarity Network in Finland, Friends of the Earth Finland, KIOS Foundation and The Consumers’ Union of Finland. Layout: Petri Clusius/Amfi bi ky Publication date: October 2019 Cover photo: A worker on a tea plantation in the Nuwara Eliya district in Sri Lanka. The person in the photo is not connected to Finnwatch’s investigation. Finnwatch will not publish pictures of the individuals who were intervie- wed for this report due to consideration for their safety. Contents 1. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................. 4 2. INDIA: THE NILGIRIS ..................................................................................................................... -

The Way of Tea

the way of tea | VOLUME I the way of tea 2013 © CHADO chadotea.com 79 North Raymond Pasadena, CA 91103 626.431.2832 DESIGN BY Brand Workshop California State University Long Beach art.csulb.edu/workshop/ DESIGNERS Dante Cho Vipul Chopra Eunice Kim Letizia Margo Irene Shin CREATIVE DIRECTOR Sunook Park COPYWRITING Tek Mehreteab EDITOR Noah Resto PHOTOGRAPHY Aaron Finkle ILLUSTRATION Erik Dowling the way of tea honored guests Please allow us to make you comfortable and serve a pot of tea perfectly prepared for you. We also offer delicious sweets and savories and invite you to take a moment to relax: This is Chado. Chado is pronounced “sado” in Japanese. It comes from the Chinese words CHA (“tea”) and TAO (“way”) and translates “way of tea.” It refers not just to the Japanese tea ceremony, but also to an ancient traditional practice that has been evolving for 5,000 years or more. Tea is quiet and calms us as we enjoy it. No matter who you are or where you live, tea is sure to make you feel better and more civilized. No pleasure is simpler, no luxury less expensive, no consciousness-altering agent more benign. Chado is a way to health and happiness that people have loved for thousands of years. Thank you for joining us. Your hosts, Reena, Devan & Tek A BRIEF HISTORY OF CHADO Chado opened on West 3rd Street in 1990 as a small, almost quaint tearoom with few tables, but with 300 canisters of teas from all over the globe lining the walls. In 1993, Reena Shah and her husband, Devan, acquired Chado and began quietly revolutionizing how people in greater Los Angeles think of tea. -

Aamchi Mumbai Comes to Our Hong Kong

mbai entic Mu ost Auth The M ong Food In Hong K SUNDAY BREAKFAST Set Deals SET MENU BF01 2 VADA PAV, 1 CUTTING CHAI A Mumbai creation, this consists of a deep- fried batata vada (potato mash patty coated with chick pea flour) with spices sandwiched between two slices of pav.............$75 SET MENU THIS! T BF02 JHAKAAS! EA KHEEMA PAV.......PG 02 CHICKEN THALI.......PG 04 PAV BHAJI.......PG 05 DHAASU CHICKEN 65..PG 05 KADHAI PANEER....PG 07 GULAB JAMUN.......PG 08 1 ALOO PARANTHA WITH CURD & PICKLE ALONG WITH 1 CUTTING CHAI Stuffed pancake with mashed potatoes, leafy Aamchi Mumbai comes vegetables, radishes, cauliflower, and/or paneer (cottage cheese)...............$80 to Our Hong Kong Specials MISAL PAV Our Speciality This consists of a spicy curry primarily made of tomatoes, onion, sprouts and coriander. Topped with sev or Indian noodles and- en joyed with buns and chutney..........$60 GARLIC CHICKEN Tender cubes of chicken cooked with garlic sauce. Chicken recipes are all time favorite for all non-vegetarians. Be it starters or main course, every body loves the soft and juicy chicken. Have it with tandoori roti, chapathi or even naan breads. This Garlic Chicken Gravy tastes equally good when served with pulav or plain rice......................................$95 10% service charge extra. Taking a stroll on Juhu Beach, Served entireAnytime.. day Mumbai’s evening snack Mumbai Street headquarters, this is what you 02 can find to eat... BOMBAY CLUB SANDWICH ANDA BHURJI PAV KHEEMA PAV Our Speciality Another egg-infused dish which is very pop A famous Mumbai breakfast item consisting ular in Mumbai.This consists of scrambled of minced meat (mutton) fried with green A traditional Mumbai club sandwich is eggs with chopped tomato, onion, garlic, grilled and served with an assortment of fresh peas and coriander, among other Indian chilli powder, and other Indian condiments. -

Js-04 Tea in India N

~ ocro =======::::::li:=-The 3rd International Conference on O-CHA(Tea) Culture and Science.~00iA JS-04 TEA IN INDIA N. K. Jain International Society ofTea Science, A-298 Sarita Vihar, New Delhi, India 110076 Ph: +91-11-2694-9142, Fax: PP +91-11-2694-2222, email: [email protected] Summary The British started tea plantations in India in 1839 with seeds brought from China. The quality of the indigenous tea Camellia sinesis var assamica, was recognized in 1839. India is the largest tea producer, averaging 842 million kg or 26% of global production, grown in 129,027 holdings, 92% ofwhich are> 10 ha. North India contributes 3/4th of total production with Y4 th from South India., India consumes 77% of its produce, leaving only 200 mkg for its shrinking exports. A decade long cost-price squeeze led to economic crisis, rendering many units unsustainable. Strategies ofits scientific management are suggested. Keywords: Indian Tea, Production, Export, Consumption, Cost price squeeze; Crisis management. INTRODUCTION The British started tea plantations in 1839 with seeds brought from China after the Opium Wars threatened their 'home' supplies. The indigenous tea Camellia sinesis var assamica was grown since times immemorial, by the tribes in North East India. It was (re) discovered in 1823 but rejected as a wild plant, until 1839 when the quality of tea made from these "wild" assamica bushes was established at London Auctions. Tea plantation activity spread very quickly. In 2005 India recorded a production of 929 million kilo tea, grown on an area of 523,000 hectares, spread over 1,29,027 units, of which over 92% were less than 10 ha and only 8% (1661) were large estates in private or corporate sectors. -

Novel Bio-Chemical Profiling of Indian Black Teas with Reference to Quality Parameters B.B

alenc uiv e & eq B io io B a f v o a i l l Borse and Jagan Mohan Rao, J Bioequiv Availab 2012, S14 a Journal of a b n r i l i u DOI: 10.4172/jbb.S14-004 t y o J ISSN: 0975-0851 Bioequivalence & Bioavailability Research Article OpenOpen Access Access Novel Bio-Chemical Profiling of Indian Black Teas with Reference to Quality Parameters B.B. Borse* and L. Jagan Mohan Rao Plantation Products, Spices and Flavour Technology Department, Central Food Technological Research Institute, (Council of Scientific and Industrial Research), Mysore - 570 020, India Abstract Novel bio-chemical profiling of Indian black teas covering all the regions and seasons (s1:April-June, s2:July- Sept., s3:Oct.-Dec., s4:Jan.- Mar.) from select gardens cutting across all climatic conditions so as to represent the variables was carried out. The profiling was carried out with reference to physico-bio-chemical quality indices based on parameters as well as volatiles and non-volatiles which are important from quality viewpoint. Different fingerprint markers in terms of volatiles and non-volatiles for tea quality were identified. Seasonal variation of TF/TR ratio over tea producing region/grade and with respect to quality was deliniated. Also the seasonal variation of sum of Yamanishi-Botheju and Mahanta ratio over tea producing region/grade and concomitant tea quality profile has been deliniated. The sum of TF/TR ratios of tea and the sum of the VFC ratios (Yamanishi-Botheju ratio and Mahanta ratio) added together is proposed for the first time as a new and novel quality index, hence forth referred to as Borse- Rao quality index, considered to be an overall quality indicator of tea as both the non-volatiles and volatiles are given due consideration. -

Kangra Tea, Geographical Indication (GI)” Funded By: MSME

ANNEXURE-IV Proceedings of One Day Workshop on “Kangra Tea, Geographical Indication (GI)” Funded by: MSME. Govt. of India Venue: IHBT, PALAMPUR Date: 24.3.2017 Organized by State Council for Science, Technology & Environment, H.P The State Council for Science, Technology & Environment, Shimla organized a One Day Awareness Workshop on “Kangra Tea: Geographical Indication” for Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) for the Kangra Tea planters at IHBT, Palampur on 24th March,2017. Hon’ble Speaker HP Vidhan Sabha Sh. B.B.L.Butail was the Chief Guest on the occasion while Sh.K.G Butail, President, Kangra Small Tea Planters Association, Palampur was the guest of honour. Sh.Sanjay Kumar, Director, IHBT, CSIR, Palampur, HP was special guest for the workshop. Other dignitaries present on the occasion included Sh. Kunal Satyarthi, IFS, Joint Member Secretary, SCSTE and Mr Anupam Das, Deputy Director, Tea Board Palampur. On behalf of host organization Dr. Aparna Sharma, Senior Scientific Officer, Sh. Shashi Dhar Sharma, SSA, Ms. Ritika Kanwar, Scientist B and Mr. Ankush Prakash Sharma, Project Scientist were present during the workshop. Inaugural Session: Sh. Kunal Satyarthi, IFS, Joint Member Secretary, SCSTE Shimla welcomed all the dignitaries, resource persons, Kangra Tea Planters and the print and electronic media at the workshop on behalf of the State Council for Science, Technology & Environment, H.P. He highlighted the history of Kangra Tea, impact of 1905 Kangra earthquake on Kangra Tea Production and ways to overcome the loss by adopting multiple cropping patterns as in Assam and Nilgiri, blending of tea from various regions and focused Felicitation of Sh. -

Tulsi Tea 'The Sacred Herb' Or 'Holy Basil' Due to Its Potential to Lift up Your Spirits

Menu Hot Beverages Assam Tea Camomille Darjeeling Earl Grey English Breakfast Green Tea Jasmine Peppermint Café Latte Cappuccino Freshly Brewed Coffee Espresso Macchiato Mochaccino Cold Beverages Fresh Fruit Juice Seasonal Iced Tea Lemon, Mint, Apple, Peach Cold Coffee Milk Shake Vanilla, Chocolate, Strawberry, Banana Lassi Plain, Salted, Sweet, Masala Aerated Beverages Domestic Bottled Water Qua Evian Sparkling Water Specialty Tea's Formosa Green Tea Grown among peach, apricot & plum trees. This tea is one bud & a single tiny leaf in a spiral shape. It is full-bodied with a sweet aftertaste. Tulsi Tea 'The Sacred Herb' or 'Holy Basil' due to its potential to lift up your spirits. These properties support and promote general health, and enhance body's natural defense mechanism against stress and diseases. Kashmiri Kahwa Cloves, cinnamon and ginger–the 3 ingredients used is this recipe mixed with Kashmiri green tea and flavoured with cardamom is what helps relieve headache and maintain fluid levels. Organic Darjeeling Harvested according to the lunar cycles, which assure that they have already matured to yield the healthiest and fullest flavour of the leaves. Because of this it is known for its distinct rich texture with a hint of sharpness to its taste. Nilgiri Tea Intensely aromatic, fragrant and flavoured tea grown in the southern portion of the Western Ghats with in Southern India. This tea is believed to contain antioxidants, subsequently assisting in lowering down the cholesterol level. Government Taxes as ApplicableFood & Beverage 17.44%Aerated Beverage 24.94%We levy No Service Charge Soft Beverages BEVERAGE LIST NON ALCOHOLIC COCKTAIL SOFT BEVERAGES All prices are exclusive of government tax.