CICE Policy Brief

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fact Book 2020(英語版)All.Indd

with Other Universities Overview and Comparisons Overview 13. Income and Expenditure 13-1. Budgeted Income and Expenditure Number of Faculty Number of Faculty and Staff Members Kyushu Universityʼs budgeted income and expenditures have been on a downward trend since FY 2018, the year the campus relocation was completed. ◆Kyushu University◆ Number of Students Budgeted Income and Expenditure (¥million) 148,822 150,000 139,617 Admissions 133,429 133,160 148,822 128,240 129,470 139,617 125,852 126,898 133,429 133,160 115,593 129,470 128,240 125,852 126,898 115,593 100,000 Enrollment Conferred 50,000 Graduate Degrees Degrees Graduate 0 Career Paths and Career Paths Employment Status Employment 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 (FY) Budgeted income Budgeted expenditure Examinations Success in Qualification *Source: Kyushu University Information ◆Other Universities (FY2019) ◆ Research Budgeted Income and Expenditure The University 261,172 of Tokyo 261,172 International Kyoto 177,863 University 177,863 Osaka 157,952 University 157,952 Industry-University- Tohoku 146,961 Government Collaboration Government University 146,961 Kyushu 125,852 University 125,852 Nagoya 106,118 University Hospital University University 106,118 Hokkaido 100,552 University 100,552 Income and Expenditure 0 50,000 100,000 150,000 200,000 250,000 300,000 Income and Expenditure (¥million) Budgeted income Budgeted expenditure *Source: Websites and Information for each university Education Programs Selection of Research/ 174 KYUSHU UNIVERSITY FACT BOOK 2020 Overview -

Textbook on Social Services and Social Work in Singapore

NEEDS AND ISSUES OF PERSONS WITH DISABILITY Rosaleen Ow1 David W. Rothwell2 This is the preprint version of the work. The definitive version was published in Social Work in the Singapore Context as: Ow, R. & Rothwell, D. W. (2011). Needs and issues of persons with disability. In K. Mehta & A. Wee (Eds.), Social Work in the Singapore Context (2nd ed.; pp. 241-270). Singapore: Pearson. 1 Department head, National University of Singapore Department of Social Work, Blk AS3 Level 4, 3 Arts Link, Singapore 117570; [email protected] 2 Assistant Professor, McGill University School of Social Work 3506 University Street, Suite 300, Montreal, Quebec H3A 2A7; [email protected], http://www.mcgill.ca/socialwork/faculty/rothwell Social Work in the Singapore Context 8 Needs and Issues of Persons with Disability Rosaleen Ow and David Rothwell Introduction The collection of comprehensive statistical data on disabled persons is a worldwide problem due to various reasons, including: a) the lack of a universal definition of disability; b) a coherent system for data collection as disability can be social, physical or mental; and c) the tendency to under- report due to stigma and lack of knowledge. Despite these limitations, estimates suggest that 10% of the world’s population lives with a disability, the largest minority (United Nations Programme on Disabilities, 2010). However, measuring disability is not consistent across contexts For example, the incidence of disability in the latest US Census was estimated at 19.3% of the civilian non-institutionalised population, much higher than the UN standard (Waldrop & Stern, 2003). In Singapore, a 10% incidence of disability as proposed by the UN translates into about 490,000 persons based on a population of 4.9 million in 2009 Statistics Singapore, 2010). -

Robotics Laboratory List

Robotics List (ロボット技術関連コースのある大学) Robotics List by University Degree sought English Undergraduate / Graduate Admissions Office No. University Department Professional Keywords Application Deadline Degree in Lab links Schools / Institutes or others Website Bachelor Master’s Doctoral English Admissions Master's English Graduate School of Science and Department of Mechanical http://www.se.chiba- Robotics, Dexterous Doctoral:June and December ○ http://www.em.eng.chiba- 1 Chiba University ○ ○ ○ Engineering Engineering u.jp/en/ Manipulation, Visual Recognition Master's:June (Doctoral only) u.jp/~namiki/index-e.html Laboratory Innovative Therapeutic Engineering directed by Prof. Graduate School of Science and Department of Medical http://www.tms.chiba- Doctoral:June and December ○ 1 Chiba University ○ ○ Surgical Robotics ○ Ryoichi Nakamura Engineering Engineering u.jp/english/index.html Master's:June (Doctoral only) http://www.cfme.chiba- u.jp/~nakamura/ Micro Electro Mechanical Systems, Micro Sensors, Micro Micro System Laboratory (Dohi http://global.chuo- Graduate School of Science and Coil, Magnetic Resonance ○ ○ Lab.) 2 Chuo University Precision Mechanics u.ac.jp/english/admissio ○ ○ October Engineering Imaging, Blood Pressure (Doctoral only) (Doctoral only) http://www.msl.mech.chuo-u.ac.jp/ ns/ Measurement, Arterial Tonometry (Japanese only) Method Assistive Robotics, Human-Robot Communication, Human-Robot Human-Systems Laboratory http://global.chuo- Graduate School of Science and Collaboration, Ambient ○ http://www.mech.chuo- 2 Chuo University -

A Voice of Our Own: Rethinking the Disabled in the Historical Imagination of Singapore Zhuang Kuan Song National University of S

A VOICE OF OUR OWN: RETHINKING THE DISABLED IN THE HISTORICAL IMAGINATION OF SINGAPORE ZHUANG KUAN SONG NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2010 A VOICE OF OUR OWN: RETHINKING THE DISABLED IN THE HISTORICAL IMAGINATION OF SINGAPORE ZHUANG KUAN SONG (B.A.(Hons.), National University of Singapore) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2010 “I long to accomplish a great and noble task, but it is my chief duty to accomplish small tasks as if they were great and noble…” Helen Keller, 1880-1968 Author, Political Activist, Lecturer Deaf Blind Person Acknowledgements This research had been a long, arduous but entirely rewarding process. Coming to this stage has not been easy, and apologies are in order for those whom I had inadvertently or accidentally offended throughout this process. Throughout the two years of my postgraduate studies, I learnt much about myself and about the lives of people with disabilities. Understanding the mentalities of disabled people and how their lives are structured has become second nature to me and I hope had made me a better person. This research would not have been possible without the support from my supervisor, Dr Sai Siew Min. She had been my academic supervisor since my Bachelors’ and had given me guidance since. Dr Sai had been encouraging and I thank her for the patience she had shown while I was formulating the direction of the research. Consulting her had been a breeze for she would gladly put aside whatever she was doing, whenever I entered her office without prior appointment. -

Title Context, Service Provision, and Reflections on Future Directions of Support for Individuals with Intellectual Disability I

Title Context, service provision, and reflections on future directions of support for individuals with intellectual disability in Singapore Author(s) Kenneth K. Poon Source Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 12(2), 100–107 Published by Wiley Copyright © 2015 Wiley This is the peer reviewed version of the following article: Poon, K. K. (2015). Context, service provision, and reflections on future directions of support for individuals with intellectual disability in Singapore. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 12(2), 100– 107. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jppi.12121, which has been published in final form at http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jppi.12121. This article may be used for non-commercial purposes in accordance with Wiley Terms and Conditions for Self-Archiving. This document was archived with permission from the copyright owner. Context, Service Provision, and Reflections on Future Directions of Support for Individuals With Intellectual Disability in Singapore Manuscript ID: JPPID-13-0078.R2 Special Issue: World Disability Report Corresponding Author Kenneth K. Poon Nanyang Technological University, National Institute of Education 1 Nanyang Walk Singapore 637616Tel: +65 6790 3226; E-mail: [email protected] Keywords: disability, early intervention, intellectual disability, Singapore, special education Running Head: Disability Support in Singapore Date Received: 02-Dec-2013 Date Accepted: 24-Jun-2014 1 Abstract The author examined how individuals with intellectual disabilities (ID) are supported in Singapore and what are the needs for further service development. Service provision for individuals with disabilities in Singapore is broadly reflective of its changing needs as a developing nation. -

Disability Rights and Inclusion in 1980S Singapore

Disability and the Global South, 2020 OPEN ACCESS Vol.7, No. 1, 1813-1829 ISSN 2050-7364 www.dgsjournal.org At the Margins of Society: Disability Rights and Inclusion in 1980s Singapore Kuansong Victor Zhuanga* aPhD Candidate in Disability Studies, University of Illinois at Chicago Macquarie University, Sydney. Corresponding Author- Email: [email protected] A new era focused on the inclusion of disabled people in society has emerged in recent years around the world. The emergence of this particular discourse of inclusion can be traced to the 1980s, when disabled people worldwide gathered in Singapore to form Disabled Peoples’ International (DPI) and adopted a language of the social model of disability to challenge their exclusion in society. This paper examines the responses of disabled people in Singapore in the decade in and around the formation of DPI. As the social model and disability rights took hold in Singapore, disabled people in Singapore began to advocate for their equal participation in society. In mapping some of the contestations in the 1980s, I expose the logics prevailing in society and how disabled people in Singapore argued for their inclusion in society as well as its implications for our understanding of inclusion in Singapore today. Keywords: Disability studies; Singapore; inclusion; normalcy Introduction In 1981, disabled people from all around the world came to Singapore to form Disabled Peoples’ International (DPI), heralding a new era of disability activism and their call for emancipation from oppression in society. The clarion call – a voice of our own – was to have repercussions around the world. As James Charlton (1998) notes, disabled activists internationally attributed their political awakening to the first world congress and the ideas that circulated from there. -

Creating an Inclusive Classroom

AY 2017 CREATING AN INCLUSIVE CLASSROOM: COUNTRY CASE STUDIES ANALYSIS ON MAINSTREAM TEACHERS’ TEACHING-EFFICACY AND ATTITUDES TOWARDS STUDENTS WITH SPECIAL NEEDS IN JAPAN AND SINGAPORE A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN INTERNATIONAL STUDIES ADRIAN YAP YEI MIAN Major in Policy Analysis of Comparative and 4014S316-1 International Education GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ASIA AND PACIFIC STUDIES WASEDA UNIVERSITY PROF. LIU-FARRER GRACIA C.E. PROF. KURODA, KAZUO D.E. PROF. KATSUMA YASUSHI PROF. TARUMI YUKO KEYWORDS TEACHING-EFFICACY, ATTITUDES, JAPAN, SINGAPORE, SPECIAL EDUCATION, INCLUSIVE EDUCATION, THEORY OF PLANNED BEHAVIOUR, THEORY OF SELF-EFFICACY, MIXED-METHODS, DISABILITIES i ABSTRACT “Creating an inclusive classroom” is no easy feat for education policy-makers and school educators to include students with special educational needs in the regular school settings. How we want to idealise our schools to become an inclusive educational institution depends on how the school leaders, educators and policy-makers put in their measures to realise inclusivity at schools. For the past few decades, inclusive education was often pushed to the forefront of educational agenda and it became a frequently talked-about topic at educational conferences. Past research indicated that teachers’ teaching-efficacy and attitudes created significant impacts on their teaching competence and students’ achievements (Avramidis, Bayliss & Burden, 2000; Scruggs & Mastropieri, 1996; Soodak & Podell, 1994; Wilczenski, 1992). This dissertation focusses on two country case studies in Japan and Singapore. The study employed a sequential mixed method design starting with the quantitative research followed by qualitative phase: Phase 1, a questionnaire-type research and Phase 2, a semi-structured interview research. -

Semantic Integration of User Data-Models and Processes

Program Committee CANDAR 2016 Track 1: Algorithms and Applications Chair: Akihiro Fujiwara, Kyushu Institute of Technology, Japan Stéphane Devismes, VERIMAG UMR 5104, France Man Duhu, Shenzhen Institutes of Advanced Technology, China Masaru Fukushi, Yamaguchi University, Japan Teofilo Gonzalez, University of California, USA Qianping Gu, Simon Fraser University, Canada Xin Han, Dalian University of Technology, China Fumihiko Ino, Osaka University, Japan Hirotsugu Kakugawa, Osaka University, Japan Sayaka Kamei, Hiroshima University, Japan Christos Kartsaklis, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, USA Yosuke Kikuchi, Tsuyama National College of Technology, Japan Yonghwan Kim, Nagoya Institute of Technology, Japan Guoqiang Li, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, China Yamin Li, Hosei University, Japan Ami Marowka, Bar-Ilan University, Israel Eiji Miyano, Kyushu Institute of Technology, Japan Hiroaki Mukaidani, Hiroshima University, Japan Takayuki Nagoya, Tottori University of Environmental Studies, Japan Fukuhito Ooshita, NAIST, Japan Ke Qiu, Brock University, Canada Wei Sun, Data61/CSIRO, Australia Daisuke Takafuji, Hiroshima University, Japan Satoshi Taoka, Hiroshima University, Japan Jerry Trahan, Louisiana State University, USA Yushi Uno, Osaka Prefecture University, Japan Shingo Yamaguchi, Yamaguchi University, Japan Hiroshi Yamamoto, Ritsumeikan University, Japan Track 2: Architecture and Computer System Chair: Michihiro Koibuchi, National Institute of Informatics, Japan Martti Forsell, VTT, Finland Ikki Fujiwara, National Institute of Informatics, -

Hicells 2020)

Hawaiʻi International Conference on English Language and Literature Studies (HICELLS 2020) “Trends in Research and Pedagogical Innovations in English Language and Literature” CONFERENCE PROGRAM March 13 -14, 2020 HICELLS 2020 03/13-14/2020 Hawaii International Conference on English Language and Literature Studies (HICELLS 2020) English Department University of Hawaii at Hilo March 13-14, 2020 CONFERENCE PROGRAM DAY 1 (FRIDAY) March 13, 2020 Time Venue: UCB 100 8:00 – 8:30 Conference Registration 8:30 – 8:45 Kipaepae 8:45 – 9:00 Welcome Address Dr Bonnie D. Irwin Chancellor University of Hawaii at Hilo 9:00 – 9:45 Keynote Address 1 Minds, Machines and Language: What Does the Future Hold? William O’Grady University of Hawaii at Manoa Hawaii, USA BREAK: UCB 127 9:45- 10:00 PARALLEL SESSION 1 10:00 – 12:20 Room: UCB 127 (10:00-12:20) No. Presenters Papers 1 Michio Hosaka The Emergence of Functional Projections in the Nihon University History of English 2 Susana T. Udoka A Study of English and Annang Clause Syntax: Akwa Ibom State University From the View Point of Grammaticality and Global Obio Akpa Campus Intelligibility HICELLS 2020 2 HICELLS 2020 03/13-14/2020 3 Quentin C. Sedlacek Contestation, Reification, and African American California State University English in College Linguistics Courses Monterey Bay 4 Hiromi Otaka On the Aspect Used in the Subordinate Clause of Kwansei Gakuin University “This is the first time ~” in English 5 Chiu-ching Tseng English Word Boundary Perception by Mandarin George Mason University Native Speakers 6 Yumiko Mizusawa An Analysis of Lexicogrammatical and Semantic Seijo University Features in Academic Writing by Japanese EFL Learners 7 Noriko Yoshimura Japanese EFL Learners’ Structural University of Shizuoka Misunderstanding: ECM Passives in L2 English Mineharu Nakayama The Ohio State University Atsushi Fujimori University of Shizuoka Room: UCB 101 (10:00-12:20) No. -

(As of Ay 1, 2018) 1-1. Overview of Kyushu University 1-1-1

Overview and Comparisons With Other Universities 1 vervie and Comarisons ith ther Universities (as of ay 1, 2018) 1-1. Overview of Kyushu University 1-1-1. Composition of Schools and Faculties Schools (12) raduate Schools (18) raduate Schools (Faculties) (16) School of Interdisciplinary Science and Innovation raduate School of Humanities Faculty of Humanities raduate School of Integrated Sciences for lobal School of etters Faculty of Social and Cultural Studies Society School of ducation raduate School of Human-nvironment Studies Faculty of Human-nvironment Studies School of aw raduate School of aw Faculty of aw School of conomics aw School (Professional raduate School) Faculty of conomics School of Science raduate School of conomics Faculty of anguages and Cultures School of edicine raduate School of Science Faculty of Science School of Dentistry raduate School of athematics Faculty of athematics School of Pharmaceutical Sciences raduate School of Systems ife Sciences Faculty of edical Sciences School of ngineering raduate School of edical Sciences Faculty of Dental Science School of Design raduate School of Dental Science Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences School of Agriculture raduate School of Pharmaceutical Sciences Faculty of ngineering raduate School of ngineering Faculty of Design Faculty of Information Science and lectrical raduate School of Design ngineering raduate School of Information Science and Faculty of ngineering Sciences lectrical ngineering Interdisciplinary raduate School of ngineering Faculty of Agriculture Sciences -

Lecture Notes in Physics

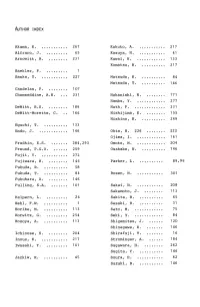

AUTHOR INDEX Akama, K ............ 267 Kakuto, A ............. 217 Alfraro, J .......... 65 Kasuya, N ............ 41 Arnowitt, R ......... 231 Kawai, H ............. 133 Komatsu, H ........... 217 Baekler, P .......... I Banks, T ............ 227 Matsuda, H ........... 84 Matsuda, T ........... 146 Candelas, P ......... 107 Chamseddine, A.H .... 231 Nakanishi, N ......... 171 Nambu, Y ............. 277 DeWitt, B.S ......... 189 Nath, P .............. 231 DeWitt-Morette, C. .. 166 Nishijima, K ......... 155 Nishino, H ........... 249 Eguchi, T ........... 133 Endo, J ............. 146 Ohta, N. 226 ........ 222 Ojima, I ............. 161 Fradkin, E.S ........ 284,293 Omote, M ............. 204 Freund, P.G.O ....... 259 Osakabe, N ........... 146 Fujii, Y ............ 272 Fujiwara, H ......... 146 Parker, L ........... 89,96 Fukuda, R ........... 58 Fukuda, T ........... 84 Rosen, N ............ 301 Fukuhara, A ......... 146 Fulling, S.A ........ 101 Sakai, N ....... ..... 208 Sakamoto, J ......... 113 Halpern, L .......... 26 Sakita, B ............ 65 Hehl, F.W ........... I Sasaki, R ........... 31 Horibe, M ........... 113 Sato, M ............. 75 Horwitz, G .......... 254 Seki, Y ............. 84 Hosoya, A ........... 113 Shigemitsu, J ....... 120 Shinagawa, K ........ 146 Ichinose, S ......... 204 Shirafuji, T ........ 16 Inoue, K ............ 217 Strominger, A ....... 184 Iwasaki, Y .......... 141 Sugawara, H ......... 262 Sugita, Y ........... 146 Jackiw, R ........... 45 Suura, H ............ 62 Suzuki, R ........... 146 307 Takeshita, S ........ 217 Tauber, G.E ......... 301 Tomimatsu, A ........ 36 Tonomura, A ......... 146 Townsend, P.K ....... 240 Tseytlin, A.A ....... 284,293 Umezaki, H .......... 146 Viallet, C.M ........ 116 Yokoyama, K ......... 84 Yoneya, T ........... 79 Yoshi4, T ........... 141 List of Participants Akama, K. DeWitt, B.S. Saitama Medical School Department of Physics Japan University of Texas at Austin USA Aoki, K. RIFP, Kyoto University DeWitt-Morette, C. Japan Department of Astronomy University of Texas at Austin USA Arafune, J. -

The Japanese Society of Hypertension Committee for Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension

Hypertension Research (2014) 37, 254–255 & 2014 The Japanese Society of Hypertension All rights reserved 0916-9636/14 www.nature.com/hr The Japanese Society of Hypertension Committee for Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension CHAIRPERSON Kazuaki SHIMAMOTO (Sapporo Medical University) WRITING COMMITTEE Katsuyuki ANDO (University of Tokyo) Ikuo SAITO (Keio University) Toshihiko ISHIMITSU (Dokkyo Medical University) Shigeyuki SAITOH (Sapporo Medical University) Sadayoshi ITO (Tohoku University) Kazuyuki SHIMADA (Jichi Medical University) Masaaki ITO (Mie University) Kazuaki SHIMAMOTO (Sapporo Medical University) Hiroshi ITOH (Keio University) Tatsuo SHIMOSAWA (University of Tokyo) Yutaka IMAI (Tohoku University) Hiromichi SUZUKI (Saitama Medical University) Tsutomu IMAIZUMI (Kurume University) Norio TANAHASHI (Saitama Medical University) Hiroshi IWAO (Osaka City University) Kouichi TAMURA (Yokohama City University) Shinichiro UEDA (University of the Ryukyus) Takuya TSUCHIHASHI (Steel Memorial Yahata Hospital) Makoto UCHIYAMA (Uonuma Kikan Hospital) Mitsuhide NARUSE (NHO Kyoto Medical Center) Satoshi UMEMURA (Yokohama City University) Koichi NODE (Saga University) Yusuke OHYA (University of the Ryukyus) Jitsuo HIGAKI (Ehime University) Katsuhiko KOHARA (Ehime University) Naoyuki HASEBE (Asahikawa Medical College) Hisashi KAI (Kurume University) Toshiro FUJITA (University of Tokyo) Naoki KASHIHARA (Kawasaki Medical School) Masatsugu HORIUCHI (Ehime University) Kazuomi KARIO (Jichi Medical University) Hideo MATSUURA (Saiseikai Kure Hospital)