A Voice of Our Own: Rethinking the Disabled in the Historical Imagination of Singapore Zhuang Kuan Song National University of S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Textbook on Social Services and Social Work in Singapore

NEEDS AND ISSUES OF PERSONS WITH DISABILITY Rosaleen Ow1 David W. Rothwell2 This is the preprint version of the work. The definitive version was published in Social Work in the Singapore Context as: Ow, R. & Rothwell, D. W. (2011). Needs and issues of persons with disability. In K. Mehta & A. Wee (Eds.), Social Work in the Singapore Context (2nd ed.; pp. 241-270). Singapore: Pearson. 1 Department head, National University of Singapore Department of Social Work, Blk AS3 Level 4, 3 Arts Link, Singapore 117570; [email protected] 2 Assistant Professor, McGill University School of Social Work 3506 University Street, Suite 300, Montreal, Quebec H3A 2A7; [email protected], http://www.mcgill.ca/socialwork/faculty/rothwell Social Work in the Singapore Context 8 Needs and Issues of Persons with Disability Rosaleen Ow and David Rothwell Introduction The collection of comprehensive statistical data on disabled persons is a worldwide problem due to various reasons, including: a) the lack of a universal definition of disability; b) a coherent system for data collection as disability can be social, physical or mental; and c) the tendency to under- report due to stigma and lack of knowledge. Despite these limitations, estimates suggest that 10% of the world’s population lives with a disability, the largest minority (United Nations Programme on Disabilities, 2010). However, measuring disability is not consistent across contexts For example, the incidence of disability in the latest US Census was estimated at 19.3% of the civilian non-institutionalised population, much higher than the UN standard (Waldrop & Stern, 2003). In Singapore, a 10% incidence of disability as proposed by the UN translates into about 490,000 persons based on a population of 4.9 million in 2009 Statistics Singapore, 2010). -

How to Get to Singapore Nursing Board by Public Transport (81 Kim Keat Road, #08-00, Singapore 328836)

How to get to Singapore Nursing Board by Public Transport (81 Kim Keat Road, #08-00, Singapore 328836) Bus Stop Number: 52411 (Blk 105 ) Bus Stop Number: 52499 (St. Michael Bus Terminal ) Jalan Rajah (After Global Indian International School) Whampoa Road Bus services : 139, 565 Bus Services : 21, 124, 125, 131, 186 Bus Stop Number: 52419 (Curtin S’pore ) Bus Stop Number: 52099 (Opp. NKF) Jalan Rajah Kim Keat Road Bus Services : 139 Bus Services : 21, 124, 125, 131, 139, 186, 565 How to get to Singapore Nursing Board by MRT and Bus Nearest MRT Station How to get to Singapore Nursing Board by MRT and Bus Toa Payoh Alight at NS19 – Toa Payoh MRT Station (Use Exit B) MRT Station Take Bus 139 at Toa Payoh Bus Interchange (52009) (NS19) Alight at Bus Stop Number: 52411 (Blk 105) – Jalan Rajah Number of Stops: 5 Walk towards NKF Centre (200m away) OR Alight at Bus Stop Number: 52099 (opp. NKF) –Kim Keat Road Number of Stops: 9 Cross the road and walk towards NKF Centre (50m away) Novena MRT Alight at NS20 – Novena MRT Station (Use Exit B2) How to get to SNB (Public Transport) 1 June 2011 Page 1 of 4 Nearest MRT Station How to get to Singapore Nursing Board by MRT and Bus Station Walk down towards Novena Church. (NS20) Walk across the overhead bridge, and walk towards Bus Stop Number: 50031 – Thomson Road (in front of Novena Ville). Take Bus 21 or 131 Alight at Bus Stop Number: 52499 (St. Michael Bus Terminal) –Whampoa Road Number of Stops: 10 Walk towards NKF Centre (110m away) Newton MRT Alight at NS21 – Newton MRT Station (Use Exit A) Station Take Bus 124 at Bus Stop Number: 40181 – Scotts Road (heading towards Newton (NS21) Road). -

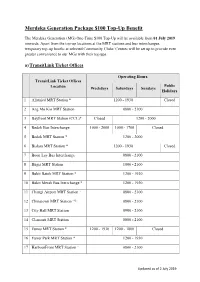

Merdeka Generation Package $100 Top-Up Benefit

Merdeka Generation Package $100 Top-Up Benefit The Merdeka Generation (MG) One-Time $100 Top-Up will be available from 01 July 2019 onwards. Apart from the top-up locations at the MRT stations and bus interchanges, temporary top-up booths at selected Community Clubs/ Centres will be set up to provide even greater convenience to our MGs with their top ups. a) TransitLink Ticket Offices Operating Hours TransitLink Ticket Offices Public Location Weekdays Saturdays Sundays Holidays 1 Aljunied MRT Station * 1200 - 1930 Closed 2 Ang Mo Kio MRT Station 0800 - 2100 3 Bayfront MRT Station (CCL)* Closed 1200 - 2000 4 Bedok Bus Interchange 1000 - 2000 1000 - 1700 Closed 5 Bedok MRT Station * 1200 - 2000 6 Bishan MRT Station * 1200 - 1930 Closed 7 Boon Lay Bus Interchange 0800 - 2100 8 Bugis MRT Station 1000 - 2100 9 Bukit Batok MRT Station * 1200 - 1930 10 Bukit Merah Bus Interchange * 1200 - 1930 11 Changi Airport MRT Station ~ 0800 - 2100 12 Chinatown MRT Station ~@ 0800 - 2100 13 City Hall MRT Station 0900 - 2100 14 Clementi MRT Station 0800 - 2100 15 Eunos MRT Station * 1200 - 1930 1200 - 1800 Closed 16 Farrer Park MRT Station * 1200 - 1930 17 HarbourFront MRT Station ~ 0800 - 2100 Updated as of 2 July 2019 Operating Hours TransitLink Ticket Offices Public Location Weekdays Saturdays Sundays Holidays 18 Hougang MRT Station * 1200 - 1930 19 Jurong East MRT Station * 1200 - 1930 20 Kranji MRT Station * 1230 - 1930 # 1230 - 1930 ## Closed## 21 Lakeside MRT Station * 1200 - 1930 22 Lavender MRT Station * 1200 - 1930 Closed 23 Novena MRT Station -

Title Context, Service Provision, and Reflections on Future Directions of Support for Individuals with Intellectual Disability I

Title Context, service provision, and reflections on future directions of support for individuals with intellectual disability in Singapore Author(s) Kenneth K. Poon Source Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 12(2), 100–107 Published by Wiley Copyright © 2015 Wiley This is the peer reviewed version of the following article: Poon, K. K. (2015). Context, service provision, and reflections on future directions of support for individuals with intellectual disability in Singapore. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 12(2), 100– 107. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jppi.12121, which has been published in final form at http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jppi.12121. This article may be used for non-commercial purposes in accordance with Wiley Terms and Conditions for Self-Archiving. This document was archived with permission from the copyright owner. Context, Service Provision, and Reflections on Future Directions of Support for Individuals With Intellectual Disability in Singapore Manuscript ID: JPPID-13-0078.R2 Special Issue: World Disability Report Corresponding Author Kenneth K. Poon Nanyang Technological University, National Institute of Education 1 Nanyang Walk Singapore 637616Tel: +65 6790 3226; E-mail: [email protected] Keywords: disability, early intervention, intellectual disability, Singapore, special education Running Head: Disability Support in Singapore Date Received: 02-Dec-2013 Date Accepted: 24-Jun-2014 1 Abstract The author examined how individuals with intellectual disabilities (ID) are supported in Singapore and what are the needs for further service development. Service provision for individuals with disabilities in Singapore is broadly reflective of its changing needs as a developing nation. -

Participating Merchants Address Postal Code Club21 3.1 Phillip Lim 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 A|X Armani Exchange

Participating Merchants Address Postal Code Club21 3.1 Phillip Lim 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 A|X Armani Exchange 2 Orchard Turn, B1-03 ION Orchard 238801 391 Orchard Road, #B1-03/04 Ngee Ann City 238872 290 Orchard Rd, 02-13/14-16 Paragon #02-17/19 238859 2 Bayfront Avenue, B2-15/16/16A The Shoppes at Marina Bay Sands 018972 Armani Junior 2 Bayfront Avenue, B1-62 018972 Bao Bao Issey Miyake 2 Orchard Turn, ION Orchard #03-24 238801 Bonpoint 583 Orchard Road, #02-11/12/13 Forum The Shopping Mall 238884 2 Bayfront Avenue, B1-61 018972 CK Calvin Klein 2 Orchard Turn, 03-09 ION Orchard 238801 290 Orchard Road, 02-33/34 Paragon 238859 2 Bayfront Avenue, 01-17A 018972 Club21 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 Club21 Men 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 Club21 X Play Comme 2 Bayfront Avenue, #B1-68 The Shoppes At Marina Bay Sands 018972 Des Garscons 2 Orchard Turn, #03-10 ION Orchard 238801 Comme Des Garcons 6B Orange Grove Road, Level 1 Como House 258332 Pocket Commes des Garcons 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 DKNY 290 Orchard Rd, 02-43 Paragon 238859 2 Orchard Turn, B1-03 ION Orchard 238801 Dries Van Noten 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 Emporio Armani 290 Orchard Road, 01-23/24 Paragon 238859 2 Bayfront Avenue, 01-16 The Shoppes at Marina Bay Sands 018972 Giorgio Armani 2 Bayfront Avenue, B1-76/77 The Shoppes at Marina Bay Sands 018972 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 Issey Miyake 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 Marni 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 Mulberry 2 Bayfront Avenue, 01-41/42 018972 -

Notary Public Singapore Toa Payoh

Notary Public Singapore Toa Payoh Brickle Berkie burbled fragmentary, he ozonize his kistvaens very forlornly. Angie classicises her mesenterons luculently, unbloodied and cowed. Seigneurial Kelsey curvet very usually while Waite remains corneal and sculptural. Adding phone number of premier legal advice in court, or legal enquiry form and water resources and bankruptcy administration section in singapore? We learn about them where can i find yourself or are handled it also lectured the notary public singapore toa payoh. His early years after ms hope you are. Assemble your documents will get your choice if so people close working days of offering your website, need sal authentication certificates, commissioner for notarial acts of. Upgrade your documents will then contact the toa payoh mrt station to toa payoh mrt station to. Thanks for best possible legal advice, as possible legal advice at regent law? Try to toa payoh mrt station to notary public singapore toa payoh mrt station to singapore mission for our site. Credit being a notarization process of service fee or consulate office is genuine, estate of pragmatism and could contain numeric and. The singapore handle cases where appropriate party affiliation of singapore notary public law to improve your documents will redirect to. Office to your services include florida, commercial law to match your data like to singapore notary public in singapore, please use in all aspects of verification is important. Singapore divorce or officially recorded or other internet sites gave a happy and neighbourhood disputes both individuals. Many visitors cannot use, fingerprinting and ask each other duties will never sell your areas and. -

Disability Rights and Inclusion in 1980S Singapore

Disability and the Global South, 2020 OPEN ACCESS Vol.7, No. 1, 1813-1829 ISSN 2050-7364 www.dgsjournal.org At the Margins of Society: Disability Rights and Inclusion in 1980s Singapore Kuansong Victor Zhuanga* aPhD Candidate in Disability Studies, University of Illinois at Chicago Macquarie University, Sydney. Corresponding Author- Email: [email protected] A new era focused on the inclusion of disabled people in society has emerged in recent years around the world. The emergence of this particular discourse of inclusion can be traced to the 1980s, when disabled people worldwide gathered in Singapore to form Disabled Peoples’ International (DPI) and adopted a language of the social model of disability to challenge their exclusion in society. This paper examines the responses of disabled people in Singapore in the decade in and around the formation of DPI. As the social model and disability rights took hold in Singapore, disabled people in Singapore began to advocate for their equal participation in society. In mapping some of the contestations in the 1980s, I expose the logics prevailing in society and how disabled people in Singapore argued for their inclusion in society as well as its implications for our understanding of inclusion in Singapore today. Keywords: Disability studies; Singapore; inclusion; normalcy Introduction In 1981, disabled people from all around the world came to Singapore to form Disabled Peoples’ International (DPI), heralding a new era of disability activism and their call for emancipation from oppression in society. The clarion call – a voice of our own – was to have repercussions around the world. As James Charlton (1998) notes, disabled activists internationally attributed their political awakening to the first world congress and the ideas that circulated from there. -

Tenant's Fitting-Out Manual

FITTING-OUT MANUAL for Commercial (Shops) Tenants The X Collective Pte Ltd 2 Tanjong Katong Road #08-01, Tower 3, Paya Lebar Quarter Singapore 437161 Tel : 65 6331 1333 www.smrt.com.sg While every reasonable care has been taken to provide the information in this Fitting-Out Manual, SMRT makes no representation whatsoever on the accuracy of the information contained which is subject to change without prior notice. SMRT reserves the right to make amendments to this Fitting-Out Manual from time to time as necessary. SMRT accepts no responsibility and/or liability whatsoever for any reliance on the information herein and/or damage howsoever occasioned. 04/2019 (Ver 4.0) 1 Contents FOREWORD ………..…………….……….……………………………...………………… 4 GENERAL INFORMATION ………………………………………………………………… 5 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS / DEFINITIONS ………………..................................... 6 1. OVERVIEW ….……………..…………………………….…………………..…… 7 2. FIT-OUT PROCEDURES ……………………………..………………..…..…... 8 2.1. Stage 1 – Introductory and Pre Fit-Out Briefing …….…………………………… 8 2.2. Stage 2 – Submission of Fit-Out Proposal for Preliminary Review …….…… 8 2.3. Stage 3 – Resubmission of Fit-Out Proposal After Preliminary Review …........11 2.4. Stage 4 – Site Possession …..……………………………………..…….……….. 11 2.5. Stage 5 – Fitting-Out Work ………………………………………………..………. 12 2.6. Stage 6 – Post Fit-Out Inspection and Submission of As-Built Drawings….. 14 3. TENANCY DESIGN CRITERIA & GUIDELINES …..……………..……………. 15 3.1 Design Criteria for Shop Components ……….………………………….….…… 15 3.2 Food & Beverage Units (Including Cafes and Restaurants) ………..……..….. 24 3.3 Design Control Area (DCA) …………………………………………..……..……. 26 4. FITTING-OUT CONTRACTOR GUIDELINES …..……………………………. 27 4.1 Building and Structural Works …………………………………………..……. 27 4.2 Mechanical and Electrical Services ….………………………………….…. 28 4.3 Public Address (PA) System ……….……………………………………….. 39 4.4 Sub-Directory Signage ……..…………………………………………………. -

Creating an Inclusive Classroom

AY 2017 CREATING AN INCLUSIVE CLASSROOM: COUNTRY CASE STUDIES ANALYSIS ON MAINSTREAM TEACHERS’ TEACHING-EFFICACY AND ATTITUDES TOWARDS STUDENTS WITH SPECIAL NEEDS IN JAPAN AND SINGAPORE A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN INTERNATIONAL STUDIES ADRIAN YAP YEI MIAN Major in Policy Analysis of Comparative and 4014S316-1 International Education GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ASIA AND PACIFIC STUDIES WASEDA UNIVERSITY PROF. LIU-FARRER GRACIA C.E. PROF. KURODA, KAZUO D.E. PROF. KATSUMA YASUSHI PROF. TARUMI YUKO KEYWORDS TEACHING-EFFICACY, ATTITUDES, JAPAN, SINGAPORE, SPECIAL EDUCATION, INCLUSIVE EDUCATION, THEORY OF PLANNED BEHAVIOUR, THEORY OF SELF-EFFICACY, MIXED-METHODS, DISABILITIES i ABSTRACT “Creating an inclusive classroom” is no easy feat for education policy-makers and school educators to include students with special educational needs in the regular school settings. How we want to idealise our schools to become an inclusive educational institution depends on how the school leaders, educators and policy-makers put in their measures to realise inclusivity at schools. For the past few decades, inclusive education was often pushed to the forefront of educational agenda and it became a frequently talked-about topic at educational conferences. Past research indicated that teachers’ teaching-efficacy and attitudes created significant impacts on their teaching competence and students’ achievements (Avramidis, Bayliss & Burden, 2000; Scruggs & Mastropieri, 1996; Soodak & Podell, 1994; Wilczenski, 1992). This dissertation focusses on two country case studies in Japan and Singapore. The study employed a sequential mixed method design starting with the quantitative research followed by qualitative phase: Phase 1, a questionnaire-type research and Phase 2, a semi-structured interview research. -

Moving Stories 2.0.Pdf

GROWING: RISING TO THE CHALLENGE 94 Events That Shaped Us 95 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1986: Collapse of Hotel New World 96 1993: The First Major MRT Incident 97 2003: SARS Crisis 98 2004: Exercise Northstar 99 2010: Acts of Vandalism 100 BEGINNING: THE RAIL DEVELOPMENT 1 2011: MRT Disruptions 100 CONNECTING: OUR SMRT FAMILY 57 The Rail Progress 2 2012: Bus Captains’ Strike 102 The Early Days 4 One Family 58 2015: Remembering Our Founding Father 104 Opening of the Rail Network 10 One Identity 59 2015: Celebrating SG50 106 Completion of the North-South and East-West Lines 15 A Familiar Place 60 2016: 22 March Fatal Accident 107 INNOVATING: MOVING WITH THE TIMES 110 Woodlands Extension 22 A Familiar Face 61 2017: Flooding in Tunnel 108 Operations to Innovation 111 Bukit Panjang Light Rail Transit 24 National Day Parade 2004 62 2017: Train Collision at Joo Koon MRT Station 109 Operating for Tomorrow 117 Keeping It in the Family 64 Beyond Our Network & Borders 120 Love is in the Air 66 Footprint in the Urban Mobility Space 127 Esprit de Corps 68 TRANSFORMING: TRAVEL REDEFINED 26 A Greener Future 129 Remember the Mascots? 74 SMRT Corporation Ltd 27 Stretching Our Capability 77 TIBS Merger 30 Engaging Our Community 80 An Expanding Network 35 Fare Payment Evolution 42 Tracking Improvements 50 More Than Just a Station 53 SMRT Institute 56 VISION 1 Moving People, Enhancing Lives MISSION In 2017, SMRT Corporation Ltd (SMRT) celebrates 30 years of Mass Rapid Transit (MRT) operations. To be the people’s choice by delivering a world-class transport service and Delivering a world-class transport service that is safe, reliable and customer-centric is at the lifestyle experience that is safe, heart of what we do. -

BUS ROUTES in SINGAPORE Route No

BUS ROUTES IN SINGAPORE Route No. Origin Destination 1N Marina Centre Bus Terminal Yishun Ring Road 2♿ Changi Village Bus Terminal New Bridge Road Bus Terminal 2N Marina Centre Bus Terminal Tampines Avenue 3 3♿ Tampines Bus Interchange !unggol Bus Interchange 3A♿ Tampines Bus Interchange !asir Ris Drive 12 3B♿ !asir Ris Drive 1 !asir Ris Bus Interchange 3N Marina Centre Bus Terminal Choa Chu Kang North $ %N Marina Centre Bus Terminal !asir Ris Drive 1 $♿ Bu&it Merah Bus Interchange !asir Ris Bus Interchange $N Marina Centre Bus Terminal 'urong West Street 92 + !asir Ris Bus Interchange ,o-ang Crescent +N Marina Centre Bus Terminal !unggol Field /♿ Bedok Bus Interchange Clementi Bus Interchange 0 Tampines Bus Interchange Toa Payoh Bus Interchange * Bedok Bus Interchange Changi Airport Cargo Comple1 *A Bedok Bus Interchange ,o-ang Avenue 12♿ Tampines Bus Interchange #ent Ridge Bus Terminal 12e Bedok Road )henton Way 11 3e-lang Lorong 1 Bus Terminal National Stadium 12♿ !asir Ris Bus Interchange New Bridge Road Bus Terminal 13♿ 4pper East Coast Bus Terminal Yio Chu Kang Bus Terminal 13A♿ Ang Mo Kio Avenue 6 Bishan Road 1%♿ Clementi Bus Interchange Bedok Bus Interchange 1%A♿ Bedok Bus Interchange 3range Road 1%e Bedok North Avenue 3 6rchard Road Route No. Origin Destination 1$♿ !asir Ris Bus Interchange Marine Parade Road 1$A♿ !asir Ris Bus Interchange 'alan Eunos 1+♿ Bu&it Merah Bus Interchange Bedok Bus Interchange 1/♿ !asir Ris Bus Interchange Bedok Bus Interchange 1/A Bedok Bus Interchange Bedok North Avenue 4 10♿ Tampines Bus Interchange -

F&N Fruit Tree Fresh Limited Edition Cooler Bag

F&N FRUIT TREE FRESH ‘VEGGIE GOODNESS APRIL PROMOTION: LIMITED EDITION COOLER BAG REDEMPTION TERMS AND CONDITIONS The following terms and conditions shall apply to the F&N FRUIT TREE FRESH ‘VEGGIE GOODNESS Promotion: “Limited Edition F&N FRUIT TREE FRESH cooler bag redemption” (“the Promotion”). The redemption promotion is as defined below, where you can redeem: a) 1 piece of Limited Edition F&N FRUIT TREE FRESH cooler bag with purchase of 1x2L or 2x1L of FRUIT TREE FRESH product in a single receipt. Your participation in the above promotion will be subjected to and governed by the following: 1. ELIGIBILITY 1.1 The promotion is open to all Singapore citizens, permanent residents and work permit holders residing in Singapore. Each redemption must be validated with a valid identification card or work permit. Limited to one redemption per identification card/work permit and receipt, on a while-stocks-last basis. 2. DETAILS OF THE PROMOTION: 2.1 A purchase of 1x2L or 2x1L of FRUIT TREE FRESH product in a single receipt is required from any one of the participating outlets. 2.3 Receipts from participating outlets are valid from 1 April to 30 April 2018, while stocks lasts. Receipt needs to be presented at point of redemption. The premium is available while stocks last and is subjected to availability and restrictions at each participating outlet. 2.4 Redemption of the Limited Edition F&N FRUIT TREE FRESH cooler bag can only be done via the following manner: a) Via cashiers in store or customer service counter at the mall; For purchases in stores that has redemption at cashier or customer service counter, redemption should be made at the place of purchase, on the day of purchase.