Republique Algerienne Democratique Et Populaire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Madarat F.PDF

1 2 Madarat Exploration de la Mobilité autour de la Méditerranée Recherches, communications et articles choisis this project is funded by the European Union The Arab Education Forum 6 Fares al Khoury street, Shmeisani P.O.Box 940286 Amman 11194 Jordan Tel. +962 6 5687557 fax. +962 6 5687558 www.almoultaqa.com, [email protected] Translation, editing, design and printing: funded by the European Union Research and translation for the Symposium: funded by the Anna Lindh Euro- Mediterranean foundation Editor: Serene Huleileh Translators: Hanan Kassab-Hasan (Ar-Fr), Angie Cotte (En-Fr), Amath Faye (Fr-En), Alice Guthrie (Ar-En), Tom Aplin(Ar-En), Shiar Youssef (Ar-En). English Editors: Amy Trabka, Kathy Baroody French Editor: Angie Cotte Cover design: Raouf Karray First edition: November 2013 Disclaimer: This publication reflects only the views of the authors. Neither The Project Partners, nor the European Commission can be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. 2 3 Introduction Le Projet Istikshaf Cartographie des fonds de mobilité autour de la Méditerranée Articles choisis Titre Autuer Page Mobiles oui, migrants non ? Jeunes marocains qui Elsa Mescoli 15 bougent* Le Rai: un périple dans toute la Méditerranée Said Khateeby 27 Culture et Tourisme : Comment marcher sur les Kamel Riyahi 31 sables mouvants La littérature du voyage et les carnets des Nouri Al Jarrah 42 voyageurs : Un pont entre l’Orient et l’Occident, et entre les Arabes et le monde Expériences personnelles et réflexions Titre Autuer -

Frankreichs Empire Schlägt Zurück Gesellschaftswandel, Kolonialdebatten Und Migrationskulturen Im Frühen 21

Dietmar Hüser (Hrsg.) in Zusammenarbeit mit Christine Göttlicher Frankreichs Empire schlägt zurück Gesellschaftswandel, Kolonialdebatten und Migrationskulturen im frühen 21. Jahrhundert Das Empire schlägt zurück. In vielerlei Hinsicht und mit vielfältigen Konse- quenzen. Seit fast drei Jahrzehnten zeigt sich Frankreich als verunsicherte Republik. Als gespalten auch zwischen denen, die die immer offensicht- licheren Rück- und Einflüsse des früheren Kolonialreiches als Wohltat für Gesellschaft, Politik und Kultur des ehemaligen Mutterlandes empfin- den, als Auf-bruch zu neuen Ufern. Und denen, die dies prinzipiell anders sehen, die das Konfrontieren der République une et indivisible mit einer selbstbewussten France au pluriel für den Untergang des Abendlandes halten. Zwischen jenen auch, die negativ empfundene Folgewirkungen einer beschleunigten Welt in primär kolonial- bzw. migrationsdimensio- nierte Begründungskontexte einordnen. Und jenen, die auf das Versagen der „Großen Politik“ verweisen, auf anachronistische Elitenrekrutierung, auf ein erstarrtes republikanisches Modell fernab der gelebten Realität breiter Bevölkerungskreise. Frankreichs Empire schlägt zurück Empire Frankreichs kassel ISBN 978-3-89958-902-3 university press Dietmar Hüser Dietmar Dietmar Hüser (Hrsg.) in Zusammenarbeit mit Christine Göttlicher Frankreichs Empire schlägt zurück Gesellschaftswandel, Kolonialdebatten und Migrationskulturen im frühen 21. Jahrhundert kassel university press Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar ISBN print: 978-3-89958-902-3 ISBN online: 978-3-89958-903-0 URN: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0002-9037 © 2010, kassel university press GmbH, Kassel www.upress.uni-kassel.de Umschlagbild mit freundlicher Genehmigung des Zeichners Plantu aus dem Buch: Plantu, Je ne dois pas dessiner ..., Paris (Editions du Seuil) 2006, S.136-137. -

Various La Nuit Du Raï Mp3, Flac, Wma

Various La Nuit Du Raï mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Folk, World, & Country Album: La Nuit Du Raï Country: France Released: 2011 Style: Raï MP3 version RAR size: 1613 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1496 mb WMA version RAR size: 1741 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 364 Other Formats: MP3 AC3 MPC MOD AHX AIFF MP4 Tracklist Hide Credits CD1 Raï RnB 1 –El Matador Featuring Amar* Allez Allez 3:31 2 –Cheb Amar Sakina 3:24 3 –Dj Idsa Featuring Big Ali & Cheb Akil Hit The Raï Floor 3:44 4 –Dj Idsa Featuring Jacky Brown* & Akil* Chicoter 4:02 5 –Swen Featuring Najim Emmène Moi 3:44 6 –Shyneze* Featuring Mohamed Lamine All Raï On Me 3:25 –Elephant Man Featuring Mokobé Du 113* & 7 Bullit 3:22 Sheryne 8 –L'Algérino Marseille By Night 3:41 9 –L'Algérino Featuring Reda Taliani M'Zia 3:56 10 –Reyno Featuring Nabil Hommage 5:19 11 –Hass'n Racks* Wati By Raï 2:50 12 –Hanini Featuring Zahouania* Salaman 5:21 –DJ Mams* Featuring Doukali* Featuring 13 Hella Décalé (Version Radio Edit) 3:16 Jahman On Va Danser 14 –Cheb Fouzi Featuring Alibi Montana 2:56 Remix – Soley Danceflor 15 –Cheb Rayan El Babour Kalae Mel Port 3:46 16 –Redouane Bily El Achra 4:04 17 –Fouaz la Classe Poupouna 4:38 18 –Cheb Didine C Le Mouve One Two Three 4:03 19 –Youness Dépassite Les Limites 3:40 20 –Cheb Hassen Featuring Singuila Perle Rare 3:26 CD2 Cœur Du Raï 1 –Cheba Zahouania* & Cheb Sahraoui Rouhou Liha 2 –Cheba Zahouania* Achkha Maladie 3 –Bilal* Saragossa 4 –Abdou* Balak Balak 5 –Abdou* Apple Masqué 6 –Bilal* Tequiero 7 –Bilal* Un Milliard 8 –Khaled Didi 9 –Sahraoui* & Fadela* -

Música Popular Y Sociedad En La Argelia Actual

MÚSICA POPULAR Y SOCIEDAD EN LA ARGELIA ACTUAL LUIS F. BERNABÉ PONS El gran profe a S!la"#$n enía poder so(re odos los genios *!e p!e(lan la vida de los seres ,!#anos. E' a -apacida&. *!e '/lo 0l a esora(a. le ,acía do#inar a e' os seres de fuego. *!ienes le o(edecían ciega#ente para poner en pie odo a*!el e&)1cio *!e el gran re" constr!- or desea(a. En !na o-a')/n, sin e#(argo. Salo#/n les ordenó constr!ir !n gran palacio en las ierras de Argel. En a*!ella o-a')/n los genios na )+os le respondieron: “¡Iwa, ya nabí! Lakin ancor un bière!”. Es e -,)' e. *!e 'e p!ede es-!-,ar -on #)l for#as &)' )n as an o en la -ap) al &e Argel)a -o#o en '! 3ona &e )n4!en-)a, )l!' ra &e for#a ,!#or%' )-amen e &esp)a&a&a lo *!e es !na &e las -ara- er%' )-as *!e #!-,o' &e lo' argel)no' atr)(!"en a '! prop)a 'o-)eda& y a '% #)'#o'2 la pas)+)&a& y la iner-)a c%+)-as. Mu-,as son las razones que se p!eden &ar para ese 5!)-)o y #!-,as 'on las *!e ello' #)'#o' &an ―a no 'er *!e a ! preg!n a respon&an -on el #)'#o lema―2 &egra&a-)/n 'o-)al. )n5!' o repar o econ/#)-o. au ar*!%a &e lo' po&eres pol% )-o' en #ano' &e -as as &epreda&oras. -

Du Contact Des Langues Dans La Chanson Raï Cas Du Chanteur BILAL

République Algérienne Démocratique et Populaire Ministère de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche Scientifique Université Abdelhamid Ibn Badis de Mostaganem Faculté des Langues Étrangères Département de Français MASTER OPTION : Langue et Communication Du contact des langues dans la Chanson Raï Cas du chanteur BILAL Présenté par : KEDDARI Cherifa Devant le jury composé de : Examinatrice : Mme BENGUEDDACHE Khèira Promotrice : Mme TILIKETE Farida Présidente : Mme BENBOUZIANE Hafida Année universitaire 2018/2019 Remerciements Au terme de ce travail, je remercie Dieu Tout-Puissant de nous avoir donné le courage, la santé et la volonté pour réaliser ce modeste travail. Je remercie tout particulièrement mon encadreur Dr Farida Tilikete pour ses conseils précieux, ses encouragements, pour sa disponibilité surtout et la qualité de son encadrement. Je tiens à exprimer ma gratitude à mes précieux parents qui m’ont encouragé et soutenue tout au long de ce travail. Je remercie profondément mon frère Mohammed et ma sœur Soria qui, par le biais de leurs Contributions diverses, mon aidés, encouragés et soutenues tout au long de l’année universitaire. J’adresse mes sincères remerciements aux membres du jury d’avoir accepté d’évaluer ce mémoire. Mes remerciements les plus vifs vont aussi à tous mes enseignants du département de français de l’université de « Abdelhamid Ibn Badis » de Mostaganem pour leurs orientations et pour leurs encouragements. Enfin, je remercie toutes les personnes qui ont contribué de près ou de loin à l’élaboration de ce mémoire. DéDicace À Mes chers parents : Monsieur et Madame KEDDARI table des matières Introduction générale …………………………………………………………………..P7 Chapitre 1 : Cadre Contextuel 1. -

Tesi Doctoral Ruben Gomez Muns

LA WORLD MUSIC EN EL MEDITERRÁNEO (1987-2007): 20 AÑOS DE ESCENA MUSICAL, GLOBALIZACIÓN E INTERCULTURALIDAD Rubén Gómez Muns ADVERTIMENT. L'accés als continguts d'aquesta tesi doctoral i la seva utilització ha de respectar els drets de la persona autora. Pot ser utilitzada per a consulta o estudi personal, així com en activitats o materials d'investigació i docència en els termes establerts a l'art. 32 del Text Refós de la Llei de Propietat Intel·lectual (RDL 1/1996). Per altres utilitzacions es requereix l'autorització prèvia i expressa de la persona autora. En qualsevol cas, en la utilització dels seus continguts caldrà indicar de forma clara el nom i cognoms de la persona autora i el títol de la tesi doctoral. No s'autoritza la seva reproducció o altres formes d'explotació efectuades amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva comunicació pública des d'un lloc aliè al servei TDX. Tampoc s'autoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant als continguts de la tesi com als seus resums i índexs. ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis doctoral y su utilización debe respetar los derechos de la persona autora. Puede ser utilizada para consulta o estudio personal, así como en actividades o materiales de investigación y docencia en los términos establecidos en el art. 32 del Texto Refundido de la Ley de Propiedad Intelectual (RDL 1/1996). Para otros usos se requiere la autorización previa y expresa de la persona autora. -

Las Voces De La Emigración Magrebí

70 CULTURAS 10. 2011 Las voces de la emigración magrebí RABAH MEZOUANE ace algo menos de cuarenta años, las músicas del Magreb y de Periodista y crítico Oriente Próximo estaban condenadas a la marginalidad, al fondo musical, director de la de los numerosos cafés regentados por emigrantes, exceptuan- programación musical del Institut du Monde do los países de origen y algunos enclaves de las comunidades de Arabe, París, Francia. emigrantes en Francia. Desde los años 70-80, una generación de Hartistas magrebíes, decididamente modernos, a semejanza de Khaled, Idir, Cheb Mami, Souad Massi o Rachid Taha, supo dar una dimensión internacional a un patrimonio musical que únicamente pedía volver. Los años 90-2000 estuvieron ›Imagen de una marcados a la vez por artistas que revisaron el patrimonio de los emigrantes, tal actuación del grupo marroquí Nass el fue el caso de la Orquesta Nacional de Barbès o Hakim y Mouss, y por un regre- Ghiwan. Cortesía de so a la marginalidad y al gueto de las comunidades. Y ello luchando constan- Rabah Mezouane. temente contra los terribles prejuicios y las dudosas de la emigración magrebí)–, muchas formaciones construcciones del tipo “magrebí igual a terrorista o integraron sin complejo los acordes magrebíes en delincuente”. sus composiciones. Fue el caso de los Négresses Ver- En Francia, las músicas del Magreb y de Oriente tes, cuyo primer álbum, llamado sin tapujos, Mlah Próximo, con una riqueza y una diversidad innega- (“bien” en árabe), conquistó el Reino Unido y los bles, jamás fueron juzgadas en su justo valor a pe- Estados Unidos. Los Gypsy Kings construyeron su sar del gran número de artistas internacionales que prestigio a nivel mundial mediante la recuperación bebieron en sus fuentes. -

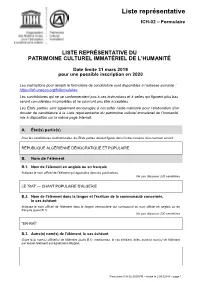

Liste Représentative

Liste représentative ICH-02 – Formulaire LISTE REPRÉSENTATIVE DU PATRIMOINE CULTUREL IMMATÉRIEL DE L’HUMANITÉ Date limite 31 mars 2019 pour une possible inscription en 2020 Les instructions pour remplir le formulaire de candidature sont disponibles à l’adresse suivante : https://ich.unesco.org/fr/formulaires Les candidatures qui ne se conformeraient pas à ces instructions et à celles qui figurent plus bas seront considérées incomplètes et ne pourront pas être acceptées. Les États parties sont également encouragés à consulter l’aide-mémoire pour l’élaboration d’un dossier de candidature à la Liste représentative du patrimoine culturel immatériel de l’humanité, mis à disposition sur la même page Internet. A. État(s) partie(s) Pour les candidatures multinationales, les États parties doivent figurer dans l’ordre convenu d’un commun accord. RÉPUBLIQUE ALGÉRIENNE DÉMOCRATIQUE ET POPULAIRE B. Nom de l’élément B.1. Nom de l’élément en anglais ou en français Indiquez le nom officiel de l’élément qui apparaîtra dans les publications. Ne pas dépasser 230 caractères LE "RAÏ" — CHANT POPULAIRE D'ALGERIE B.2. Nom de l’élément dans la langue et l’écriture de la communauté concernée, le cas échéant Indiquez le nom officiel de l’élément dans la langue vernaculaire qui correspond au nom officiel en anglais ou en français (point B.1). Ne pas dépasser 230 caractères "ER-RAÏ" B.3. Autre(s) nom(s) de l’élément, le cas échéant Outre le(s) nom(s) officiel(s) de l’élément (point B.1), mentionnez, le cas échéant, le/les autre(s) nom(s) de l’élément par lequel l’élément est également désigné. -

Programme Du Festival

PROGRAMME DU FESTIVAL SCENE D’HONNEUR : 12/07/2012 A PARTIR DE 21H00 ARTISTE SCÉNES CONDITION 3ÉME LAURÉAT RAI ACADEMY PLACE D'HONNEUR G/P MIMOUN RAFROUA PLACE D'HONNEUR G/P ROCK RAI 107 QUATER PLACE D'HONNEUR G/P FNAIR PLACE D'HONNEUR G/P CHEB AKIL PLACE D'HONNEUR G/P CHEB MAMI PLACE D'HONNEUR G/P DJ PLACE D'HONNEUR G/P 13/07/2012 A PARTIR DE 21H ARTISTE SCÉNES CONDITION 2ÉME LAURÉAT RAI ACADEMY PLACE D'HONNEUR G/P CHEB SOUNA PLACE D'HONNEUR G/P MOUSS MAHIR PLACE D'HONNEUR G/P CHEB ABBAS PLACE D'HONNEUR G/P CHEB FAUDEL PLACE D'HONNEUR G/P CHEB BILAL PLACE D'HONNEUR G/P DJ PLACE D'HONNEUR G/P 14/07/2012 A PARTIR DE 21H00 ARTISTE SCÉNES CONDITION 1ER LAURÉAT RAI ACADEMY PLACE D'HONNEUR G/P CHEB KIRIS PLACE D'HONNEUR G/P RAMI PLACE D'HONNEUR G/P CHEBA ZAHWANIA PLACE D'HONNEUR G/P CHEB KHALED PLACE D'HONNEUR G/P STATIA PLACE D'HONNEUR G/P DJ PLACE D'HONNEUR G/P ANIMATIONS DE VILLE : PLACE 16 AOUT PLACE 9 JUILLET PLACE 3 MARS FOLKLORE BERKANE FLKLORE JERADA FOLKLORE OUJDA DIMANCHE 08 TROUPE AFRICAINE DU TROUPE AFRICAINE DU TROUPE AFRICAINE JUILLET DJIBOUTI COMORES DU NIGER ACROBATES GNAWA BREAK DANCE FOLKLORE DEBDOU FOLKLORE TAOURIRT FOLKLORE BERGUEM TROUPE AFRICAINE TROUPE AFRICAINE TROUPE AFRICAINE LUNDI 09 JUILLET DU MALI MAURITANIE GUINÉE BISSAU ISSAWA ACROBATES GNAWA FOLKLORE FOLKLORE LAAOUINAT FOLKLORE SAIDIA BERKANE MARDI 10 JUILLET TROUPE AFRICAINE GUINÉE TROUPE AFRICAINE TROUPE AFRICAINE EQUATORIALE BURUNDI TCHAD ACROBATES ISSAWA ACROBATES FOLKLORE FIGUIG FOLKLORE GUERCIF FOLKLORE AHFIR MERCREDI 11 TROUPE AFRICAINE TROUPE AFRICAINE -

LE MONDE/PAGES<UNE>

EN ÎLE-DE-FRANCE a Dans « aden » tout le cinéma et une sélection de sorties Demandez notre supplément www.lemonde.fr 56e ANNÉE – Nº 17377 – 7,50 F - 1,14 EURO FRANCE MÉTROPOLITAINE JEUDI 7 DÉCEMBRE 2000 FONDATEUR : HUBERT BEUVE-MÉRY – DIRECTEUR : JEAN-MARIE COLOMBANI Marchés financiers : Au sommet de Nice, deux Europe face à face Alan Greenspan b Des dizaines de milliers de manifestants contre la mondialisation de l’économie sont attendus à Nice provoque une hausse b Les Quinze tentent de réformer les institutions de l’Union, condition préalable à tout élargissement historique vers l’Est b Le sommet s’ouvre dans un climat alourdi par les critiques sur la présidence française A LA VEILLE de l’ouverture du rues de la ville pour protester festants venant de divers pays. Jeu- neux est celui de la réforme des ins- Conseil européen de Nice, des contre la mondialisation de l’éco- di après-midi, les chefs d’Etat et de titutions de l’Union, condition à Wall Street dizaines de milliers de personnes, nomie. La municipalité a été gouvernement des Quinze de- nécessaire à l’élargissement aux selon les associations et syndicats sévèrement critiquée pour ne pas vaient commencer leurs travaux, pays de l’Est, ainsi qu’à Chypre et à EN FAISANT miroiter une bais- organisateurs, s’apprêtaient, mer- avoir prévu de dispositif particu- qui pourraient durer jusqu’à la fin Malte. Un désaccord risquerait de se des taux d’intérêt, le président credi 6 décembre, à défiler dans les lier d’hébergement pour ces mani- du week-end. -

Créations En Migrations : Parcours, Déplacements, Racinements

- . -•• CREATIONS EN MIGRATIONS PARCOURS, DEPLACEMENTS, RACINEMENTS Coordination : Marco Martiniello, Nicolas Puig et Gilles Suzanne Revue Européenne des Migrations Internationales Éditorial Marco Martiniello, Nicolas Puig et Gilles Suzanne : Créations en igrations. P, 1 u tH ~me l\t gi: racinemertk Gilles Suzanne: Ml,\siques d'.\lt rîc:. mondes de l'art et Farid ElAsri: Lexpre51ion musicale de musulmans i:=U!t l LIPi. ~ ' ri.: .1 ic r de sonorités et normativité 1to;1 u Cathertn~ Choron-Baix. Levral voyage. L'an de Dlnh Q; Lê entre e:1'il et retour Denis Vidal : Anish Kapoor et ses int:~rprètes . De la mondialisation de l'art rontempora;n à une nouvelle l tl,.i 1t:'. del' artiste uniYersel Nicolas Puig: Exils décalés. Les registres de la no~t:Algië dans les uqqw p.1Je,11111 11. ' au Liban Jean--Mkhel Lafleur et Marco Martiniello . 1 l 1 1 1 ''' ntus1oens et p. t 1p. IÎ<m électorale des tfsoyens is& us de 1 1 n .ttiu11. Le cas .des d ~u t• ni F · 1J.. ·n r" IL américaines de 2008 Kali Argyriadis : Réseaux u.ui.snallÎonaux d' artisres et rd~alisation du répertoire « afro-cubaiit » dans le ~cruz Volume 25 - N°2 - 2009 Association pour l'Étude des Migrations Internationales (AEMI) ISSN 0765-0752 - ISBN 978-2-911627-52-1 2009 Volume 25 - numéro 2 CRÉATIONS EN MIGRATIONS Parcours, déPlacements, racinements Coordination Marco MARTINIELLO, Nicolas PUIG et Gilles SUZANNE Publication éditée avec le concours de Université de Poitiers Institut des Sciences Humaines et Sociales du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (INSHS du CNRS) Direction de l’Accueil, de l’Intégration et de la Citoyenneté (DAIC) MIGRINTER (Migrations internationales, espaces et sociétés - UMR 6588) Maison des Sciences de l’Homme et de la Société de Poitiers (MSHS) Revue Européenne des Migrations Internationales 2009 (25) 2 SOMMAIRE Coordination Marco MARTINIELLO, Nicolas PUIG et Gilles SUZANNE CRÉATIONS EN MIGRATIONS Parcours, déPlacements, racinements Éditorial : Marco MARTINIELLO, Nicolas PUIG et Gilles SUZANNE 7 Créations en migrations. -

LE MONDE/PAGES<UNE>

www.lemonde.fr 58 ANNÉE – Nº 17837 – 1,20 ¤ – FRANCE MÉTROPOLITAINE --- SAMEDI 1er JUIN 2002 FONDATEUR : HUBERT BEUVE-MÉRY – DIRECTEUR : JEAN-MARIE COLOMBANI ENTREPRISES L’Europe veut supprimer Elections les droits de veto d’Etat Trente et un jours de foot dans les entreprises législatives privatisées p. 22 En Corée et au Japon, l’équipe de France remet en jeu son titre de championne du monde f Jacques Chirac MONNAIE L’ÉQUIPE de France de football teurs qui redoutent à la fois les demande a ouvert, vendredi 31 mai, la 17e hooligans et le terrorisme. une « majorité Le dollar Coupe du monde en rencontrant, Le Mondial, organisé pour la pre- à Séoul, le Sénégal qui participe mière fois en Asie, devrait aider au claire et cohérente » au plus bas pour la première fois à cette com- rapprochement entre le Japon et aux Français depuis quinze mois p. 21 pétition. Elle remet en jeu en la Corée du Sud. Encore marquée Corée du Sud et au Japon son titre par l’occupation japonaise pen- MALAWI de championne du monde acquis dant la seconde guerre mondiale, fFrançois Hollande en 1998 à Paris. L’épreuve s’achè- la Corée a toujours considéré avec l’accuse Les morts vera le 30 juin à Yokohama. méfiance son voisin japonais. Ces Chaque jour, Le Monde consacre dernières années, les deux sociétés de se comporter de la famine p. 4 un supplément de huit pages à cet ont profondément évolué, même événement. Aujourd’hui, dans sa si les rancœurs et les contentieux « en chef de parti » IMMIGRATION chronique quotidienne, Aimé Jac- demeurent.