Магистерская Диссертация Master Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Artistic Journeys in Iceland Summer Book Roundup Cultural Treasures

FRIDAY-SUNDAY, MAY 30 - JUNE 1, 2008 Wooden monkey, 1951-53, toy design by Kay Bojesen, on show in Copenhagen. Amsterdam London festival science “Holland Festival 2008” presents 35 “Dan Dare and the Birth of Hi-Tech productions of dance, literature, visual Britain” explores the role of technol- arts, theater, film, opera and music on ogy in shaping postwar Britain the theme of “Heaven and Earth.” through the science-fiction comic hero Greater Until June 22 Dan Dare. % 31-20-788-2100 Until Oct. 25, 2009 www.hollandfestival.nl % 44-870-8704-868 www.sciencemuseum.org.uk Antwerp music history “Spitalfields Festival 2008” in London’s “Antwerp=America=Red Star Line—The East End features musical perfor- Tale of a People” looks at the history mances by Gabrieli Consort & Players, Moscow of the Red Star cruise line, which the Silk String Quartet and the Royal brought more than two million Euro- Academy of Music Sinfonia with pean emigrants to the U.S. between Stephen Hough. 1873 and 1934. Spitalfields Festival National Maritime Museum From June 2 to 20 Cultural treasures Until Dec. 28 % 44-20-7377-0287 % 32-3-201-9340 www.spitalfieldsfestival.org.uk in the capital’s museum.antwerpen.be/scheepvaart museum theater “Dickens Unplugged,” written and di- suburbs Barcelona rected by Adam Long, is a musical art comedy based on the life and works of Charles Dickens. “Lothar Baumgarten: autofocus retina” Comedy Theatre shows sculptures, wall drawings, Bookings until Sept. 22 books and films by the contemporary % 44-870-0606-637 German artist (born 1944). www.theambassadors.com/comedy MACBA-Museu d’Art Contemporani Barcelona Until June 15 Munich % 34-93-4120-810 music “Richard-Strauss-Days 2008” cele- www.macba.es brates the music of Richard Strauss in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, featuring the Berlin Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra; photography the Concert Orchestra Berlin; and the “Gazes and Desire—The Photographer Chamber Orchestra Munich. -

Romanov News Новости Романовых

Romanov News Новости Романовых By Ludmila & Paul Kulikovsky №138 September 2019 New Bust to Emperor Alexander III at St. Nicholas Church in Polyarny City A monument to Emperor Alexander III was solemnly opened and consecrated in Polyarny city On the occasion of the 120th anniversary of Polyarny, a solemn opening ceremony of the bust of Emperor Alexander III took place on the territory of St. Nicholas Church. Polyarny is a city in the Murmansk region, located on the shores of the Catherine’s harbour of the Kola Bay of the Barents Sea, about 30 km from Murmansk. The city is home to the Northern Fleet and as such is a closed city. The port was laid down in the summer of 1899 and named Alexandrovsk in honour of Emperor Alexander III. In 1931 it was renamed Polyarny., Parishioners of the church of St. Nicholas the Miracle Worker and Rector Archpriest Sergei Mishchenko, initiated and sponsored the bronze bust of the great Russian Emperor Alexander III. The monument was made with donations from parishioners and in February 2019 was delivered from the workshop of Simferopol to Polyarny. The opening and consecration ceremony was conducted by Bishop Tarasiy of the North Sea and Umba. The St. Nicholas Church, with the bust of Emperor Alexander III standing under the bell tower. Stories from Crimea In 2019, there were two extraordinaire reasons to visit Crimea and Yalta in particular - the 100 years anniversary of several members of the Imperial Romanov family, including Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna, leaving Russia from Yalta - and 125 years since the repose of Emperor Alexander III in Livadia. -

DESIGN CONSTRUCTION |About Company

DESIGN CONSTRUCTION |About Company Successful work amid the First significant contract for global financial crisis; 2001 the General Design and the start of effective reconstruction of the object 2008 - 2010 cooperation with foreign with the total area over customers 15,000 m2; Establishment of the development of order 1992 Research and Production portfolio Company Metallimpress Simultaneous construction which core operation was Foundation of its own 2006 1998 of several large objects design facilities for steel structure production acting as the General Contractor Launch of construction and installation direction 1996 Entry from the regional market to the all-Russian market; taking the repeated orders from the customers; increase in production Active phase of the company 2007 capacity structuring, formation of the Design Active promotion of Team departments: Steel Structures, 2004 «turn-key» construction Detailed Design, Foundation Engineering, Reinforced Concrete Structures, Architectual Solutions, General Plan; Potential growth: the Company is able to carry up the establishment of construction and 2014 to 12 projects simultaneously finishing branch in the construction and production department 1999 2 3 |Company’s Profile |Services The basic model of collaboration with customers is turn-key construction which includes: Industrial facilities: • Automobile plants; GENERAL CONTRACT • Food production; GENERAL DESIGN • Heavy industry plants; TECHNICAL CLIENT • Light industry plants; • Chemical production; Metallimpress is a General Contractor with comprehensive approach to project implementation. • Pharmaceutical production; While performing functions of the General Contractor the Сompany puts emphasis on: • Plants of light and heavy engineering. • Qualified construction management; • Quality of technologies, materials and equipment used under construction; • Compliance with the requirements of environmental protection, occupational health and safety. -

The Chronicle of Novgorod 1016-1471

- THE CHRONICLE OF NOVGOROD 1016-1471 TRANSLATED FROM THE RUSSIAN BY ROBERT ,MICHELL AND NEVILL FORBES, Ph.D. Reader in Russian in the University of Oxford WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY C. RAYMOND BEAZLEY, D.Litt. Professor of Modern History in the University of Birmingham AND AN ACCOUNT OF THE TEXT BY A. A. SHAKHMATOV Professor in the University of St. Petersburg CAMDEN’THIRD SERIES I VOL. xxv LONDON OFFICES OF THE SOCIETY 6 63 7 SOUTH SQUARE GRAY’S INN, W.C. 1914 _. -- . .-’ ._ . .e. ._ ‘- -v‘. TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE General Introduction (and Notes to Introduction) . vii-xxxvi Account of the Text . xxx%-xli Lists of Titles, Technical terms, etc. xlii-xliii The Chronicle . I-zzo Appendix . 221 tJlxon the Bibliography . 223-4 . 225-37 GENERAL INTRODUCTION I. THE REPUBLIC OF NOVGOROD (‘ LORD NOVGOROD THE GREAT," Gospodin Velikii Novgorod, as it once called itself, is the starting-point of Russian history. It is also without a rival among the Russian city-states of the Middle Ages. Kiev and Moscow are greater in political importance, especially in the earliest and latest mediaeval times-before the Second Crusade and after the fall of Constantinople-but no Russian town of any age has the same individuality and self-sufficiency, the same sturdy republican independence, activity, and success. Who can stand against God and the Great Novgorod ?-Kto protiv Boga i Velikago Novgoroda .J-was the famous proverbial expression of this self-sufficiency and success. From the beginning of the Crusading Age to the fall of the Byzantine Empire Novgorod is unique among Russian cities, not only for its population, its commerce, and its citizen army (assuring it almost complete freedom from external domination even in the Mongol Age), but also as controlling an empire, or sphere of influence, extending over the far North from Lapland to the Urals and the Ob. -

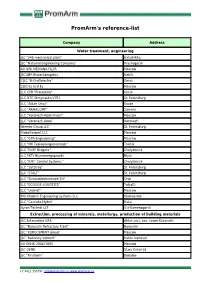

Promarm's Reference-List

PromArm's reference-list Company Address Water treatment, engineering JSC "345 mechanical plant" Balashikha JSC "National Engineering Company" Krasnogorsk AO NPK MEDIANA-FILTR Moscow JSC NPP Biotechprogress Kirishi CJSC "B-Graffelectro" Omsk CJSC Es End Ey Moscow LLC CPB "Protection" Omsk LLC NTC Stroynauka-VITU St. Petersburg LLC "Aidan Stroy" Kazan LLC "ARMACOMP" Samara LLC "Voronezh-Aqua Invest" Moscow LLC "Voronezh-Aqua" Voronezh Hermes Group LLC St. Petersburg Globaltexport LLC Moscow LLC "GPA Engineering" Moscow LLC "MK Teploenergomontazh" Troitsk LLC "NVK" Niagara " Chelyabinsk LLC PKTs Biyskenergoproekt Biysk LLC "RPK" Control Systems " Chelyabinsk LLC "SetStroy" St. Petersburg LLC "STALT" St. Petersburg LLC "Stroisantechservice-1N" Orsk LLC "ECOLINE-LOGISTICS" Tolyatti LLC "Unimet" Moscow PKK Modern Engineering Systems LLC Vladivostok LLC "Cascade-Hydro" Baku Ayron-Technik LLP Ust-Kamenogorsk Extraction, processing of minerals, metallurgy, production of building materials JSC Aldanzoloto GRK Aldan ulus, pos. Lower Kuranakh JSC "Borovichi Refractory Plant" Borovichi JSC "EUROCEMENT group" Moscow JSC "Katavsky cement" Katav-Ivanovsk AO OKHK URALCHEM Moscow JSC OEMK Stary Oskol-15 JSC "Firstborn" Bodaibo +7 8412 350797, [email protected], www.promarm.ru JSC "Aleksandrovsky Mine" Mogochinsky district of Davenda JSC RUSAL Ural Kamensk-Uralsky JSC "SUAL" Kamensk-Uralsky JSC "Khiagda" Bounty district, with. Bagdarin JSC "RUSAL Sayanogorsk" Sayanogorsk CJSC "Karabashmed" Karabash CJSC "Liskinsky gas silicate" Voronezh CJSC "Mansurovsky career management" Istra district, Alekseevka village Mineralintech CJSC Norilsk JSC "Oskolcement" Stary Oskol CJSC RCI Podolsk Refractories Shcherbinka Bonolit OJSC - Construction Solutions Old Kupavna LLC "AGMK" Amursk LLC "Borgazobeton" Boron Volga Cement LLC Nizhny Novgorod LLC "VOLMA-Absalyamovo" Yutazinsky district, with. Absalyamovo LLC "VOLMA-Orenburg" Belyaevsky district, pos. -

CRR) of Moscow Region, Start-Up Complex № 4

THE CENTRAL RING ROAD OF MOSCOW REGION INFORMATION MEMORANDUM Financing, construction and toll operation of the Central Ring Road (CRR) of Moscow Region, start-up complex № 4 July 2014, Moscow Contents Introduction 3–4 Project goals and objectives 5–7 Relevance of building the Central Ring Road Timeline for CRR project implementation Technical characteristics Brief description 8–34 Design features Cultural legacy and environmental protection Key technical aspects Concession agreement General provisions 34–37 Obligations of the concessionaire Obligations of the grantor Project commercial structure 38–46 Finance. Investment stage Finance. Operation stage Risk distribution 47–48 Tender criteria 49 Preliminary project schedule 50 The given information memorandum is executed for the purpose of acquainting market players in good time with information about the given project and the key conditions for its implementation. Avtodor SC reserves the right to amend this memorandum. 2 Introduction The investment project for construction and subsequent toll operation of the Central Ring Road of the Moscow Region A-113 consists of five Start-up complexes to be implemented on a public-private partnership basis. Start-up complex No. 4 of the Central Ring Road (the Project or SC No.4 of the CRR) provides for construction of a section of the CRR in the south-east of the Moscow Region, stretching from the intersection with the M-7 Volga express highway currently under construction to the intersection with the M-4 public highway. Section SC No. 4 of the CRR was distinguished as a separate investment project because the given section is of major significance both for the Region and for the economy of the Russian Federation in general. -

SKB (Special–Purpose Design Bureaux)

SKB Page 1 Ver. 1.0 SKB (Special–purpose Design Bureaux) 1. No. 2. Name 3. Subsidiary 4. Location 5. Branch 6. Ministry 7. Other details 8. Designer 9. Date 10. Source units 1 SKB Podlipki ARMS VSNKh (1929) formed 1929 at zavod 8 Kurchevskii 1929 G26 (1929) (renamed Kaliningrad 1938), now Korolev 1 SKB Leningrad, AERO NKAP (1939), rocket engines; Lyul'ka worked here at Sinev, Orlov 1964 D46 (N2/97, p. 16) F1 C60 (p. 63) now St NKTankProm the Kirov plant 1939-41 on gas-turbine Petersburg (1941), MObM engines; absorbed by SKB-2, LKZ to (1965)? help evacuation to Chelyabinsk; reference to Orlov joining SKB-1 in 1964 from NII-1 1 SKB Leningrad, ARMOUR NKOP (1937), suggested name of the KB z-da 174 im. Gavalov 1937-41 D6 (p. 23) now St NKTankProm Voroshilova Petersburg (1941) 2 SKB AERO an SKB-2 reported to have merged with D25 (25/2/95) the OKB-52 of Chelomei 2 SKB, LKZ Leningrad, ARMOUR NKTP (1934), originated as Byuro T-26 in 1932; from Efimov 1933, 1932-41, C81 (p. 145) C19 (pp. 384-6) D35 now St NKOP (1936), 1933 called SKB-2; design bureau of Ivanov 1933-36, 1946-97 (vol. 3/97, p. 68) C2 (p. 17) C3 (pp. Petersburg NKTankProm Leningradskii Kirovskii Zavod; evacuated Kotin 1937-41 5, 16-7) D6 (pp. 22-4) C60 (p. 359) (1941), MTM 10/41 to Chelyabinsk; returned to and 1946-51 (1945), MOP Leningrad 2/46 and renamed OKBT (1965) 1/12/51, KB-Z in 1968 and SKB 'Transmash' in c.1991 2 SKB, Chelyabinsk ARMOUR NKTankProm evacuated from Leningrad in 1941 to Kotin 1941-6 1941-4 D35 (vol. -

Transport Factor and Types of Settlement Development in the Suburban Area of the Moscow Capital Region

E3S Web of Conferences 210, 09008 (2020) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202021009008 ITSE-2020 Transport factor and types of settlement development in the suburban area of the Moscow capital region Petr Krylov1,* 1Moscow Region State University, 105005, Radio str, 10A, Moscow, Russia Abstract. The paper considers the ratio of the transport factor and the types of development of settlements in the suburban area of the Moscow capital region. The purpose of this research is to study the specific features of the development of settlements in various radial directions from the node (core) of Moscow capital region – the Moscow city. Data from publicly available electronic maps were used, including data from the public cadastral map. Historical and socio-economic prerequisites for the formation of various types of development along radial transport axes (public roads of regional and federal significance connecting Moscow with the territory of the Moscow region and other regions of Russia) are considered. Conclusions about the general and specific features of development along different directions at different distances from Moscow are drawn. The research confirms the hypothesis that the ratio of certain types of residential development along various highways differs from place to place depending on the time of the origin of the transport routes themselves, on the economically determined choice of investors, and in recent years – on the environmentally determined choice of the population. 1 Introduction The transport factor is one of the most important for the formation of the settlement system both through the level of transport development of the territory, and taking into account the variety of forms of transport accessibility and connectivity of spatial elements of the territory. -

City Abakan Achinsk Almetyevsk Anapa Arkhangelsk Armavir Artem Arzamas Astrakhan Balakovo Barnaul Bataysk Belaya Kholunitsa Belg

City Moscow Abakan Achinsk Almetyevsk Anapa Arkhangelsk Armavir Artem Arzamas Astrakhan Balakovo Barnaul Bataysk Belaya Kholunitsa Belgorod Berdsk Berezniki Biysk Blagoveshensk Bor Bolshoi Kamen Bratsk Bryansk Cheboksary Chelyabinsk Cherepovets Cherkessk Chita Chuvashiya Region Derbent Dimitrovgrad Dobryanka Ekaterinburg Elets Elista Engels Essentuki Gelendzhik Gorno-Altaysk Grozny Gubkin Irkutsk Ivanovo Izhevsk Kaliningrad Kaluga Kamensk-Uralsky Kamyshin Kaspiysk Kazan - Innopolis Kazan - metro Kazan - over-ground Kemerovo Khabarovsk Khanty-Mansiysk Khasavyurt Kholmsk Kirov Kislovodsk Komsomolsk-na- Amure Kopeysk Kostroma Kovrov Krasnodar Krasnoyarsk area Kurgan Kursk Kyzyl Labytnangi Lipetsk Luga Makhachkala Magadan Magnitogorsk Maykop Miass Michurinsk Morshansk Moscow Airport Express Moscow area (74 live cities) Aprelevka Balashikha Belozerskiy Bronnitsy Vereya Vidnoe Volokolamsk Voskresensk Vysokovsk Golitsyno Dedovsk Dzerzhinskiy Dmitrov Dolgprudny Domodedovo Drezna Dubna Egoryevsk Zhukovskiy Zaraysk Zvenigorod Ivanteevka Istra Kashira Klin Kolomna Korolev Kotelniki Krasnoarmeysk Krasnogorsk Krasnozavodsk Krasnoznamensk Kubinka Kurovskoe Lokino-Dulevo Lobnya Losino-Petrovskiy Lukhovitsy Lytkarino Lyubertsy Mozhaysk Mytischi Naro-Fominsk Noginsk Odintsovo Ozery Orekhovo-Zuevo Pavlovsky-Posad Peresvet Podolsk Protvino Pushkino Pushchino Ramenskoe Reutov Roshal Ruza Sergiev Posad Serpukhov Solnechnogorsk Old Kupavna Stupino Taldom Fryazino Khimki Khotkovo Chernogolovka Chekhov Shatura Schelkovo Elektrogorsk Elektrostal Elektrougli Yakhroma -

Typology of Russian Regions

TYPOLOGY OF RUSSIAN REGIONS Moscow, 2002 Authors: B. Boots, S. Drobyshevsky, O. Kochetkova, G. Malginov, V. Petrov, G. Fedorov, Al. Hecht, A. Shekhovtsov, A. Yudin The research and the publication were undertaken in the framework of CEPRA (Consortium for Economic Policy, Research and Advice) project funded by the Canadian Agency for International Development (CIDA). Page setting: A.Astakhov ISBN 5-93255-071-6 Publisher license ID # 02079 of June 19, 2000 5, Gazetny per., Moscow, 103918 Russia Tel. (095) 229–6413, FAX (095) 203–8816 E-MAIL – root @iet.ru, WEB Site – http://www.iet.ru Соntents Introduction.................................................................................................... 5 Chapter 1. Review of existing research papers on typology of Russian regions ........................................................................ 9 Chapter 2. Methodology of Multi-Dimensional Classification and Regional Typology in RF ................................................... 40 2.1. Tasks of Typology and Formal Tools for their Solution ................. 40 2.1.1. Problem Identification and Its Formalization .......................... 40 2.2. Features of Formal Tools ................................................................. 41 2.2.1. General approach .................................................................... 41 2.2.2. Characterization of clustering methods ................................... 43 2.2.3. Characterization of the methods of discriminative analysis ..... 45 2.3. Method for Economic Parameterisation.......................................... -

Nutrient Dynamics Along the Moskva River Under Heavy Pollution and Limited Self- Purification Capacity

E3S Web of Conferences 163, 05014 (2020) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202016305014 IV Vinogradov Conference Nutrient dynamics along the Moskva River under heavy pollution and limited self- purification capacity Maria Tereshina*, Oxana Erina, Dmitriy Sokolov, Lyudmila Efimova, and Nikolay Kasimov Lomonosov Moscow State University, Faculty of Geography, GSP-1, 1 Leninskiye Gory, 119991, Moscow, Russia Abstract. An extensive study conducted during the dry summer of 2019 provided a detailed picture of the nutrient content dynamics along the Moskva River. Water sampling at 38 locations on the main river and at 17 of its tributaries revealed a manifold increase in phosphorus and nitrogen concentrations as the river crosses the Moscow metropolitan area, which can be attributed to both direct discharge of poorly treated sewage and nonpoint urban pollution. Even at the Moskva River lower reaches, where the anthropogenic pressure on the river and its tributaries is less pronounced, the inorganic nitrogen and phosphorus content remains consistently high and exceeds the environmental guidelines by up to almost 10 times. This indicates increased vulnerability of the Moskva River ecosystem during periods of low flow, which can be a major factor of eutrophication in the entire Moskva-Oka-Volga system. Comparison of our data with some archive records shows no significant improve in the nutrient pollution of the river since the 1990s, which raises further concern about the effectiveness of water quality management in Moscow urban region. 1 Introduction Anthropogenic nutrient pollution has been considered one of the world’s major environmental problems for decades [1]. Excessive nutrient loading leads to eutrophication of lakes and streams, increasing the risk of harmful algal blooms, causing damage to aquatic ecosystems and impairing water treatment [2]. -

Departure City City Of Delivery Region Delivery Delivery Time

Cost of Estimated Departure city city of delivery Region delivery delivery time Moscow Ababurovo Moscow 655 1 Moscow Abaza The Republic of Khakassia 1401 6 Moscow Abakan The Republic of Khakassia 722 2 Moscow Abbakumova Moscow region 655 1 Moscow Abdrakhmanovo Republic of Tatarstan 682 on request Moscow Abdreevo Ulyanovsk region 1360 5 Moscow Abdulov Ulyanovsk region 1360 5 Moscow Abinsk Krasnodar region 682 3 Moscow Abramovka Ulyanovsk region 1360 5 Moscow Abramovskikh Sverdlovsk region 1360 1 Moscow Abramtsevo Moscow region 655 1 Moscow Abramtzevo (Dmitrovsky reg) Moscow region 1360 3 Moscow Abrau Durso Krasnodar region 682 1 Moscow Avvakumova Tver region 655 5 Moscow Avdotyino Moscow region 655 1 Moscow Avdotyino (Stupinsky reg) Moscow region 1360 1 Averkieva Moscow Moscow region 1360 2 (Pavlovsky Posadskiy reg) Aviation workers Moscow Moscow region 1360 1 (Odintsovskiy-one) Moscow aviators Moscow region 655 1 Moscow Aviation Moscow region 655 1 Moscow Aviation Moscow region 655 1 Moscow Motorist Arhangelsk region 655 1 Moscow avtopoligone Moscow region 1360 3 Moscow Autoroute Moscow region 655 1 Moscow agarin Moscow region 655 1 Moscow Agarin (Stupinsky reg) Moscow region 1360 1 Moscow Agafonov Moscow region 655 1 Moscow AGAFONOVA (Odintsovskiy-one) Moscow region 1360 1 Moscow Agashkino Moscow region 655 5 Moscow Ageevka Oryol Region 655 1 Moscow Agidel Republic of Bashkortostan 1360 3 Moscow Agha Krasnodar region 682 3 Moscow Agrarnik Tver region 1306 6 Moscow agricultural Republic of Crimea 682 4 Moscow agrogorodok Moscow region