Accepted Author Manuscript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lingue Migranti: a Dialectic on the Languages of Italy Published on Iitaly.Org (

Lingue Migranti: a Dialectic on the Languages of Italy Published on iItaly.org (http://108.61.128.93) Lingue Migranti: a Dialectic on the Languages of Italy Maya Paula (April 20, 2013) To anyone who does not know Italian, the language exists as an abstract fusion of a romantic ideal of the standard Tuscan dialect and stereotypical ideas of southern Italy and Italian-Americans that derive from representations in pop culture. The objective of the John D. Calandra Italian American Institute’s three-day conference is to provide a complete look at every aspect the Italian language Page 1 of 10 Lingue Migranti: a Dialectic on the Languages of Italy Published on iItaly.org (http://108.61.128.93) puzzle and its many divergent influences. April 25th, the day when Italians celebrate the anniversary of their liberation from the German Nazis and the Fascist regimes, holds yet another sense of interest for Italian Americans in New York. The John D. Calandra Italian American Institute [2] has scheduled their annual conference, “Lingue Migranti: The Global Languages of Italy and the Diaspora” to start on the Italian national holiday and extend to the 27th of April. Aside from Italy’s history surrounding both World Wars I and II, the country has had a turbulent timeline, its map having been rearranged through a myriad of appropriations and separations. Italy as it exists today has only been around for approximately 152 years, though its extensive cultural foundations stem to antiquity. While the country remains segmented into twenty distinct provinces, the stark division between them is owed to the dialects, which animate each region. -

The Pirandello Society of America BOARD of DIRECTORS Jana O

The Pirandello Society of America BOARD OF DIRECTORS Jana O’Keefe Bazzoni Stefano Boselli Janice Capuana Samantha Costanzo Burrier Mimi Gisolfi D’Aponte John Louis DiGaetani Mario Fratti Jane House Michael Subialka Kurt Taroff (Europe) Susan Tenneriello HONORARY BOARD Stefano Albertini Eric Bentley Robert Brustein Marvin Carlson Enzo Lauretta Maristella Lorch John Martello PSA The Journal of the Pirandello Society of America Susan Tenneriello, Senior Editor Michael Subialka, Editor Samantha Costanzo Burrier and Lisa Sarti, Assistant Editors Lisa Tagliaferri, Managing Editor EDITORIAL BOARD Angela Belli Daniela Bini John DiGaetani Antonio Illiano Umberto Mariani Olga Ragusa John Welle Stefano Boselli, Webmaster PSA The official publication of the Pirandello Society of America Subscriptions: Annual calendar year subscriptions/dues: $35 individual; $50 libraries; $15 students with copy of current ID. International memberships, add $10. Please see Membership form in this issue, or online: www.pirandellosocietyofamerica.org Make all checks payable to: The Pirandello Society of America/PSA c/o Casa Italiana Zerilli-Marimò 24 West 12th Street New York, NY 10011 All correspondence may be sent to the above address. Submissions: All manuscripts will be screened in a peer-review process by at least two readers. Submit with a separate cover sheet giving the author’s name and contact information. Omit self-identifying information in the body of the text and all headers and footers. Guidelines: Please use the current MLA Style Manual; use in-text references, minimal endnotes, works cited. Articles should generally be 10-20 pages in length; reviews, 2-3 pages. Please do not use automatic formatting. Send MSWord doc. -

Il Cinema Di Angelo Musco

ORTO BOTANICO e CINEFORUM DON ORIONE di Messina in collaborazione con l’ASSOCIAZIONE ANTONELLO DA MESSINA presentano la 7ª Edizione (2019) del CINEMA IN ORTO Quattro serate presso la Cavea dell’Orto IL CINEMA DI ANGELO MUSCO BIOGRAFIA - Angelo Musco nasce a Catania il 18 dicembre 1872 e muore a Milano il 6 ottobre 1937. Dopo aver esercitato i più umili mestieri, incomincia a lavorare in un Teatrino dell’Opera dei pupi e poi si dà da fare come canzonettista e macchiettista. Si trasferisce a Messina per unirsi alla Compagnia di Peppino Santoro. Nel 1900 rientra a Catania, dove viene scritturato da Giovanni Grasso, assieme al quale dà l’avvio al teatro popolare siciliano. Nel frattempo rafforza i rapporti prima con Nino Martoglio e poi – dopo aver fondato una sua Compagnia – anche con Luigi Pirandello. IL CINEMA - Dopo il film San Giovanni decollato, risalente al 1917 e diretto da Telemaco Ruggeri, su sceneggiatura di Nino Martoglio (da considerarsi irrimediabilmente perduto), l’esperienza cinematografica di Angelo Musco è tutta racchiusa nel periodo 1932-1937, in cui è il protagonista di ben 10 film, quasi tutti trasposizioni cinematografiche dei suoi successi teatrali. IL RAPPORTO CON MESSINA - Si tratta di un legame molto stretto, che affonda le sue radici in tempi lontanissimi, quando egli vi si reca per la prima volta nel 1899, incontrando il “capocomico” Peppino Santoro, che lo fa debuttare nella sua Compagnia con il nomignolo di Piripicchio. Dopo la morte di Santoro, Musco rientra a Catania; ma Messina gli rimane sempre nel cuore, tanto che vi ritorna diverse volte, anche quando - divenuto famoso - fa Compagnia a sé. -

Kampert, Magdalena Anna (2018) Self-Translation in 20Th-Century Italian and Polish Literature: the Cases of Luigi Pirandello, Maria Kuncewiczowa and Janusz Głowacki

Kampert, Magdalena Anna (2018) Self-translation in 20th-century Italian and Polish literature: the cases of Luigi Pirandello, Maria Kuncewiczowa and Janusz Głowacki. PhD thesis. https://theses.gla.ac.uk/71946/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Self-translation in 20th-century Italian and Polish literature: the cases of Luigi Pirandello, Maria Kuncewiczowa and Janusz Głowacki Magdalena Anna Kampert Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of PhD School of Modern Languages and Cultures College of Arts University of Glasgow September 2018 3 Abstract This thesis examines the phenomenon of self-translation in two different cultural contexts: the Italian context of self-translation within national borders and the Polish context of self-translation in displacement. It focuses on four case studies: Luigi Pirandello’s self-translations of ’A birritta cu ’i ciancianeddi (1916) and Tutto per bene (1920), Maria Kuncewiczowa’s self-translation of Thank you for the Rose (1950-1960) and Janusz Głowacki’s assisted self-translation of Antygona w Nowym Jorku (1992). -

Il Cinema Di Angelo Musco

ORTO BOTANICO e CINEFORUM DON ORIONE di Messina in collaborazione con l’ASSOCIAZIONE ANTONELLO DA MESSINA presentano la 7ª Edizione (2019) del CINEMA IN ORTO Quattro serate presso la Cavea dell’Orto IL CINEMA DI ANGELO MUSCO BIOGRAFIA - Angelo Musco nasce a Catania il 18 dicembre 1872 e muore a Milano il 6 ottobre 1937. Dopo aver esercitato i più umili mestieri, incomincia a lavorare in un Teatrino dell’Opera dei pupi e poi si dà da fare come canzonettista e macchiettista. Si trasferisce a Messina per unirsi alla Compagnia di Peppino Santoro. Nel 1900 rientra a Catania, dove viene scritturato da Giovanni Grasso, assieme al quale dà l’avvio al teatro popolare siciliano. Nel frattempo rafforza i rapporti prima con Nino Martoglio e poi – dopo aver fondato una sua Compagnia – anche con Luigi Pirandello. IL CINEMA - Dopo il film San Giovanni decollato, risalente al 1917 e diretto da Telemaco Ruggeri, su sceneggiatura di Nino Martoglio (da considerarsi irrimediabilmente perduto), l’esperienza cinematografica di Angelo Musco è tutta racchiusa nel periodo 1932-1937, in cui è il protagonista di ben 10 film, quasi tutti trasposizioni cinematografiche dei suoi successi teatrali. IL RAPPORTO CON MESSINA - Si tratta di un legame molto stretto, che affonda le sue radici in tempi lontanissimi, quando egli vi si reca per la prima volta nel 1899, incontrando il “capocomico” Peppino Santoro, che lo fa debuttare nella sua Compagnia con il nomignolo di Piripicchio. Dopo la morte di Santoro, Musco rientra a Catania; ma Messina gli rimane sempre nel cuore, tanto che vi ritorna diverse volte, anche quando - divenuto famoso - fa Compagnia a sé. -

Six Characters in Search of an Author Is Now Recognised As a Clas- Sic Of

Cambridge University Press 0521646189 - Pirandello: Six Characters in Search of an Author Jennifer Lorch Excerpt More information INTRODUCTION Six Characters in Search of an Author is now recognised as a clas- sic of modernism; many would echo Felicity Firth’s words, asserting that it is ‘the major single subversive moment in the history of mod- ern theatre’.1 In 1921 its story of family strife and sexual horror, set within the philosophical context of relativism, and its self-conscious form provided a double-pronged challenge: to bourgeois social values, and to the accepted mode of naturalist theatre-making. Six Characters is a deeply disturbing play as well as an intensely exciting one. It was also very influential. Written and presented in Italy long before the word ‘director’ became part of the Italian vocabulary, it gained its early European and American reputation through the work of partic- ular directors: Theodore Komisarjevsky, Brock Pemberton, Georges Pitoeff¨ and Max Reinhardt. Georges Pitoeff’s¨ production in Paris in April 1923 was to be recognised as a major force in shaping subse- quent French theatre. In other countries the influence is perhaps less distinct, and becomes blurred with that of other Pirandello plays. Certainly, Alan Ayckbourn, Samuel Beckett, Nigel Dennis, Michael Frayn, Harold Pinter, N. F. Simpson and Tom Stoppard in the UK bear affinities with Pirandello, as do Thornton Wilder and Edward Albee in the USA. The man who wrote this European classic was born in a house called ‘Caos’ on the southern coast of Sicily near Agrigento in 1867, the second child (but first son) of six children. -

Adelaide Bernardini, Writer and Playwright

ALL’OMBRA DI CAPUANA: ADELAIDE BERNARDINI SCRITTRICE E DRAMMATURGA IN THE SHADOW OF CAPUANA – ADELAIDE BERNARDINI, WRITER AND PLAYWRIGHT Dora Marchese Università di Catania Fondazione Verga RIASSUNTO Si analizzano la figura e l’opera di Adelaide Bernardini, poetessa, narratrice, giornalista e drammaturga, ricordata in genere solo come giovane moglie del grande Luigi Capuana ma che invece fu scrittrice feconda, varia nei generi e nei temi, promotrice d’istanze favorevoli alle donne, ed infaticabile imprenditrice dell’opera sua e del marito, specie in campo teatrale dove collaborò con grandi artisti e intellettuali come Nino Martoglio, Giovanni Grasso e Angelo Musco. Palabras claves: Teatro siciliano, Luigi Capuana, ribellismo femminile ABSTRACT An analysis of the figure and the works of Adelaide Bernardini – poetess, storyteller, journalist and playwright. She is usually only remembered as the young wife of the great Luigi Capuana, nevertheless she was a prolific writer who explored many genres and themes, she promoted several initiatives in favour of women and was a tireless entrepreneur for both hers and her husband’s work – especially in theatre where she worked with important artists and intellectuals as Nino Martoglio, Giovanni Grasso and Angelo Musco. Keywords: Sicilian theatre, favour of women, Luigi Capuana. Poetessa, narratrice, giornalista e drammaturga, Adelaide Bernardini è ricordata solo come la giovane moglie del celebre Luigi Capuana, mentre sulla sua opera, ampia e varia per generi e temi, è caduto irrimediabilmente l’oblio. La maggior parte di coloro che hanno scritto della Bernardini non sono stati benevoli nei suoi confronti, accusandola più o meno esplicitamente di aver utilizzato il nome e la fama del marito per fare carriera, di essere, dunque, la scaltra manipolatrice di un uomo più anziano, fragile perché innamorato, e considerandola, sostanzialmente, una scrittrice di nessun talento, parassitaria, anche in questo caso, nei confronti dell’illustre consorte. -

The University of Chicago the Art of Indeterminacy in The

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO THE ART OF INDETERMINACY IN THE PROSE WORKS OF GOLIARDA SAPIENZA A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF ROMANCE LANGUAGES AND LITERATURES BY ELANA STEPHENSON KRANZ CHICAGO, ILLINOIS DECEMBER 2016 COPYRIGHT 2016 ELANA STEPHENSON KRANZ For my family TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................................................................... v INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER ONE SAPIENZA’S CICLO AUTOBIOGRAFICO: MULTIPLE, RELATIONAL AND FUSED/FUSING SELVES ................................................................. 14 CHAPTER TWO THE INFLUENCE OF THEATER IN SAPIENZA’S PROSE WORKS..................................................... 52 CHAPTER THREE CONFINEMENT AS LIBERATION: FEMALE SPACES IN SAPIENZA’S PROSE WORKS ................ 88 CHAPTER FOUR NARRATING TRANSGRESSION; OR, WHY MODESTA KILLS ....................................................... 125 CONCLUSION .................................................................................................................................... 164 BIBLIOGRAPHY ............................................................................................................................... 170 iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my dissertation director, Rebecca West. -

Angelo Musco

PAOLO SANTACROCE CO " ''V^O' B » O >C ANGELO MUSCO ED IL TEATRO SICILIANO - ' - ' J : VS* ï ÇM-lL9 V*Sjr|HLJ - h HBEIgcB O ■ tJlHHBs--RHSMI I H H 9 M ■'■■■ r T-'r. ■ r, ' i • r.. ■ ,;.. - jìv .• r. > - *•.,«•* V ' , , -* ■ . PAOLO SANTACROCE ANGELO MUSCO ED IL TEATRO SICILIANO Salerno - Linofypografia Maffeo Spadafora - 1939-XVII. n Amico di tutti, un uomo giocondo, festoso, aneddo- tico, dagli occhi schizzanti intorno razzi di fuoco, dal cuore immenso come V immensità dell’Oceano. Un artista traboc- cante di virtù teatrali, dalla risata indiavolata, dalla comicità arguta, dal gesto rotatorio, instintivamente psicologo, fanta stico nelle improvvisazioni, rabdomantico nel mimetismo, prismatico nello spirito: ora verso la facezia e il lazzo pronto e sagace, ora verso il brio agile e colorito, ora verso la dram maticità tenue, signorile e toccante. Par di vederlo per la via avanzare a piccoli passi, ritto e pettoruto, elegantone nei modi, dal caratteristico cappello bigio a larghe falde, il lungo sigaro in bocca, gli zigomi desti, l’occhio scrutatore; ovvero, nella sua cabina teatrale, tra una scena e l’altra, con la sua testa dai riccioli radi e trasparenti, ragionatore e critico instancabile, sempre alle prese con la sua pipa o col suo .* 5 domestico Tarenzi quando accudivane ia vestizione, vibrante nei muscoli, astutamente espressivo nelle smorfie. Chi l’ha visto sulla ribalta ha potuto assaporare, con la voglia frenetica di rivederlo, la poeticità e la mobilità del suo comico umorismo tutto fatto di arguzie, di canti, di lazzi, di sgambetti, di contrazioni e di gesti più eloquenti delle parole. Era un mimo, insomma, ricco di esuberanze artistiche e perciò tutti lo consideravano un eccezionale diffusore di gioia, un mago della risata, vicino al quale le noie ed i pesi della vita andavano posti da canto. -

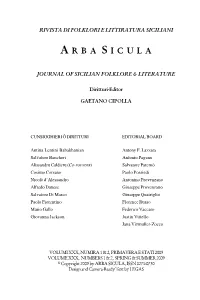

A R B a S I C U L A

RIVISTA DI FOLKLORI E LITTIRATURA SICILIANI A R B A S I C U L A JOURNAL OF SICILIAN FOLKLORE & LITERATURE Diritturi-Editor GAETANO CIPOLLA CUNSIGGHIERI Ô DIRITTURI EDITORIAL BOARD Antina Lentini Babakhanian Antony F. Lazzara Salvatore Bancheri Antonio Pagano Alissandru Caldieru (CO-FOUNDER) Salvatore Paternò Cosimo Corsano Paolo Possiedi Nicolò d’Alessandro Antonino Provenzano Alfredo Danese Giuseppe Provenzano Salvatore Di Marco Giuseppe Quatriglio Paolo Fiorentino Florence Russo Mario Gallo Federico Vaccaro Giovanna Jackson Justin Vitiello Jana Vizmuller-Zocco VOLUMI XXX, NUMIRA 1 & 2, PRIMAVERA E STATI 2009 VOLUME XXX, NUMBERS 1 & 2, SPRING & SUMMER 2009 © Copyright 2009 by ARBA SICULA, ISSN 0271-0730 Design and Camera-Ready Text by LEGAS ARBA SICULA è l’organu ufficiali dâ società siculu-americana dû stissu nomi ca si proponi comu obbiettivu principali di prisirvari, studiari, e promoviri a lingua e a cultura siciliani. ARBA SICULA è normalmenti pubblicata dui voti l’annu, ntâ primavera e nta l’autunnu. Pi comunicari direttamenti cû diritturi, pi mannari materiali pâ rivista, pi l’abbunamenti e pi informazioni supra a nostra società, scriviti a Gaetano Cipolla, Languages and Literatures Department, St. John’s University, 8000 Utopia Pkwy, Queens, NY 11439. I materiali ricevuti non si restituisciunu si nun si manna puru na busta affrancata cû nomu e indirizzu. ABBUNAMENTI Cu si abbona a la rivista, diventa automaticamenti sociu di Arba Sicula. Cu n’abbunamentu annuali i soci ricivunu du nummira di Arba Sicula (unu, si pubblicamu un numiru doppiu) e dui di Sicilia Parra. Arba Sicula è na organizzazioni senza scopu di lucru. Abbunamenti fora dî Stati Uniti $40.00 Abbunamentu regolari $35.00 Anziani e studenti $30.00 ARBA SICULA is the official journal of the Sicilian-American organization by the same name whose principal objective is to preserve, study, and promote the language and culture of Sicily. -

Schede D'archivio Della Sottoserie 03 A1 Teatro T

SCHEDE D’ARCHIVIO DELLA SOTTOSERIE 03 A1 TEATRO Il numero a sinistra di ogni documento richiama il numero d’archivio indicato nella griglia della sottoserie. T 001 FILODRAMMATICA UNIVERSITARIA 1945 Il documento è stato collazionato nella sottoserie Teatro, e contiene testi molto giovanili, di Fava ventenne. Si tratta di scenette e sketch scritti di getto, probabilmente per una rappresentazione immaginata e realizzata molto velocemente assieme agli amici della Filodrammatica. La scrittura è ancora molto acerba, ben diversa da quella dell’Innocente e di altri testi presenti in prime stesure. L’idea narrativa, al contrario, è molto bene architettata, e denota la fantasia, l’humor e anche il sarcasmo già ben presenti in Fava. I testi sono sia mano che dattiloscritti, spesso su carta del Ministro o del Ministero dell’Interno del regno. Non abbiamo alcuna congettura sulla loro provenienza. Un altro testo è redatto su un modulo del catasto (sempre del regno, marca da bollo di 4,00 Lire). Questo manoscritto, certamente di Fava per contenuto, è scritto con la matita rosso-blu tipica degli insegnati. La grafia può sembrare non di Fava, ma è molto simile a quella di altri testi di prime stesure, soprattutto di quelli scritti a matita. Del documento fanno parte anche schizzi e disegni. In particolare, il logo della Filodrammatica Universitaria, lo spettacolo di rivista che si sta allestendo, piazza del popolo di Palazzolo Acreide col municipio, e una maschera. Nel documento è conservata anche la copertina di una pubblicazione dei programmi radiofonici settimanali del 1945. 5 carte, contengono bozze di programmi, elenco di attori e personaggi. -

Universita' Degli Studi Di Catania

UNIVERSITA’ DEGLI STUDI DI CATANIA DIPARTIMENTO DI SCIENZE UMANISTICHE DOTTORATO DI RICERCA IN FILOLOGIA MODERNA XXV CICLO ALESSANDRA RAPISARDA LA CASA EDITRICE MAIMONE TESI DI DOTTORATO DI RICERCA Coordinatore: Chiar.mo Prof. Antonio Di Grado Tutor: Chiar.ma Prof.ssa Sarah Zappulla Muscarà ANNO ACCADEMICO 2013 -14 1 A miei amati genitori Vito e Angela A mio marito Achille e mio figlio Lorenzo 2 INDICE Introduzione Pag. 4 Capitolo I 1.1. L’editoria libraria catanese contemporanea. Pag. 6 Capitolo II 2.1 Biografia di Giuseppe Maimone Pag. 17 2.2 Biografia di Simona Maimone Pag. 23 2.3 I tipi Maimone Pag. 24 2.4 La Marca editoriale Pag. 26 2.5 Gli anni Ottanta Pag. 27 2.6 Dagli anni Novanta ai nostri giorni Pag. 72 Capitolo III 3.1 Le Collane Pag. 109 3.2 Archi di volta Pag. 110 3.3 Astragali Pag. 114 3.4 Le collane cinematografiche Pag. 131 3.5 Le collezioni del Museo Civico Di Castello Ursino a Catania Pag. 144 3.6 Fondazione G.&M. Giarrizzo Pag. 146 3. 7 Interventi Pag. 148 3.8 Le collane L’abaco e L’Amenano Pag. 152 3.9 Mnemosine Pag. 154 3.10 Le pietre d’angolo Pag. 259 3.11 Ossidiana Pag. 272 Conclusioni Pag. 274 Appendice Pag. 275 Bibliografia Pag. 289 3 Introduzione Attiva a Catania dal 1985, la casa editrice di Giuseppe Maimone si distingue in ambito nazionale per una editoria di qualità, con particolare riguardo ad argomenti che mettono in rilievo gli aspetti qualificanti della cultura siciliana e catanese, in particolare, non rinchiudendosi, però, in un’idea conclusa e astratta di “sicilianità”, bensì aprendosi ad altre esperienze culturali.