Six Characters in Search of an Author Is Now Recognised As a Clas- Sic Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2016 Prov. Tutte

SEZ SEZ SEZ SEZ SEZ NOMINATIVO DEL LEGALE DATA DECRETO O O O COMUNE CAP DENOMINAZIONE DELL'ORGANIZZAZIONE INDIRIZZO DELL'ORGANIZZAZIONE RECAPITI O O RAPPRESENTANTE NUMER NUMER PROV. A B C D E DECRET REGISTR TEL. 0922/442115 FAX 0922/26906 - 660556 CELL 3663319273 E- AG AGRIGENTO 92100 ASS.NE AVULSS DI AGRIGENTO ONLUS VIA EMPEDOCLE N. 145 FERA GUELI GIOVANNA A B C 340 07/03/1996 68 MAIL [email protected] AG AGRIGENTO 92100 ASSOCIAZIONE DONATORI AUTONOMA SANGUE A.D.A.S. VIA PLATONE N. 5/E TEL. 092/2586588 E-MAIL [email protected] DI FRANCESCO FILIPPO B 1547 09/10/1996 125 AG AGRIGENTO 92100 ASS.NE A.V.I.S. SEZIONE COMUNALE PIAZZA PRIMAVERA N. 15 CELL. 3208638897 CUMBO GASPARE B 1094 27/06/2000 432 AG AGRIGENTO 92100 VOLONTARIATO ITALIANO MISSIONARIO AMORE E CARITA' VIA MONCADA N. 02 tel. 092/613089 cell. 3382612199 E-MAIL [email protected] MAGRO GIUSEPPE A B 2162 18/12/2000 457 TEL. FAX 0922/607239 CELL 3666178934 E-MAIL AG AGRIGENTO 92010 ASS.NE MADRE TERESA DI CALCUTTA ONLUS VIA CAVALERI MAGAZZENI N. 111 NOBILE ANTONIO A 67 09/03/2001 512 [email protected] AG AGRIGENTO 92100 GRUPPO FRATRES FRANCESCO SAMMARTINO VIA BELVEDERE, 91 (fraz. Giardina-Gallotti) CELL. 327 9544584 FARRUGGIA CALOGERO B 3653 28/10/2002 597 AG AGRIGENTO 92100 ASS.NE FOCUS GROUP ONLUS SALITA FRANCESCO SALA N. 15 TEL.0922 22922 fax 0922 25457 GALLO CARRABBA ANTONINA A C 355 23/02/2004 705 AG AGRIGENTO 92100 ASS.NE ARMONIA SOCIALE ONLUS SALITA FRANCESCO SALA N. -

Pieghevole Alcantara 4 Ante 2

“A good wine is poetry and it is an art to produce it”: it is around this insight that the winery Dalla felice intuizione che un buon vino è “poesia” e per farlo ci vuole “arte”, nasce Al-Cantàra Al-Cantàra was created. Albeit young, the winery is establishing a reputation for itself Percorso per le Cantine . Negli ultimi anni, l’azienda si è affermata a livello nazionale ed internazionale nationally and internationally thanks to the high quality of its wines, which have been awarded site in Randazzo c/da Feudo S. Anastasia grazie all’altissima qualità dei suoi vini, riconosciuta da diversi importanti premi e, da ultimo, important prizes including the recent astounding results achieved at Vinitaly with seven wines dallo strepitoso risultato conseguito al Vinitaly: con sette vini segnalati nel 5 StarWines - selected for the 5 StarWines - The Book. There, Al-Cantàra was the second most awarded The Book, Al-Cantàra è stata la seconda azienda più premiata in Sicilia e la sesta in Italia! Il winery in Sicily and the sixth in Italy! The sophisticated and modern packaging is another packaging sofisticato e moderno è un altro tratto distintivo dei prodottiAl-Cantàra , le cui distinctive feature of the Al-Cantàra products, whose unmistakable labels are painted by inconfondibili etichette sono impreziosite dalle suggestive rappresentazioni di giovani young Sicilian artists and seek to evoke theterroir , the traditions and the culture of Sicily . artisti siciliani ed esaltano letradizioni , la cultura ed il territorio etneo . The winery takes its name from the river which flows, from the slopes of MountEtna , below L’azienda prende il nome dal fiume che, sulle pendici dell’Etna , lambisce la contrada Feudo S. -

Women As Hidden Authoritarian Figures in Luigi Pirandello's Literary

The Paradox of Identity: Women as Hidden Authoritarian Figures in Luigi Pirandello’s Literary Works Thesis Prospectus by MLA Program Primary Reader: Dr. Susan Willis Secondary Reader: Dr. Mike Winkelman Auburn University at Montgomery 1 December 2010 The Paradox of Identity: 1 Women as Hidden Authoritarian Figures in Luigi Pirandello’s Literary Works On June 28, 1867 in Sicily, Italian author and playwright Luigi Pirandello was born in a town called Caos, translated chaos, during a cholera epidemic. Pirandello’s life was marked by chaos, turmoil, and disease. He literally entered into a world of chaos. Dictated to by a tyrannical father and cared for by a meek mother, Pirandello developed an interesting view of marriage, women, and love. The passivity of his mother and eventual paranoia and insanity of his wife, Antoinette Potulano, created a premise for his literary women. As he formulated and evolved his impressions of the feminine identity from what he witnessed between his parents and experienced with his wife, the “Master of Futurism” examined the flaws of interpersonal communication between genders. He translated those experiences into his literature by depicting institutions such as marriage negatively in his early works and later shifting the bulk of his focus to gender oppositions. Pirandello explores the conundrum between men and women by placing his female characters into paradoxical roles. This thesis challenges previous criticism that maintains Pirandello’s women are “dismembered,” weak, and deconstructed characters and instead concludes that, although Pirandello’s literary women are mutable figures and his literature contains patriarchal elements, a matriarchal society dominates Pirandello’s literature. -

Lingue Migranti: a Dialectic on the Languages of Italy Published on Iitaly.Org (

Lingue Migranti: a Dialectic on the Languages of Italy Published on iItaly.org (http://108.61.128.93) Lingue Migranti: a Dialectic on the Languages of Italy Maya Paula (April 20, 2013) To anyone who does not know Italian, the language exists as an abstract fusion of a romantic ideal of the standard Tuscan dialect and stereotypical ideas of southern Italy and Italian-Americans that derive from representations in pop culture. The objective of the John D. Calandra Italian American Institute’s three-day conference is to provide a complete look at every aspect the Italian language Page 1 of 10 Lingue Migranti: a Dialectic on the Languages of Italy Published on iItaly.org (http://108.61.128.93) puzzle and its many divergent influences. April 25th, the day when Italians celebrate the anniversary of their liberation from the German Nazis and the Fascist regimes, holds yet another sense of interest for Italian Americans in New York. The John D. Calandra Italian American Institute [2] has scheduled their annual conference, “Lingue Migranti: The Global Languages of Italy and the Diaspora” to start on the Italian national holiday and extend to the 27th of April. Aside from Italy’s history surrounding both World Wars I and II, the country has had a turbulent timeline, its map having been rearranged through a myriad of appropriations and separations. Italy as it exists today has only been around for approximately 152 years, though its extensive cultural foundations stem to antiquity. While the country remains segmented into twenty distinct provinces, the stark division between them is owed to the dialects, which animate each region. -

The Pirandello Society of America BOARD of DIRECTORS Jana O

The Pirandello Society of America BOARD OF DIRECTORS Jana O’Keefe Bazzoni Stefano Boselli Janice Capuana Samantha Costanzo Burrier Mimi Gisolfi D’Aponte John Louis DiGaetani Mario Fratti Jane House Michael Subialka Kurt Taroff (Europe) Susan Tenneriello HONORARY BOARD Stefano Albertini Eric Bentley Robert Brustein Marvin Carlson Enzo Lauretta Maristella Lorch John Martello PSA The Journal of the Pirandello Society of America Susan Tenneriello, Senior Editor Michael Subialka, Editor Samantha Costanzo Burrier and Lisa Sarti, Assistant Editors Lisa Tagliaferri, Managing Editor EDITORIAL BOARD Angela Belli Daniela Bini John DiGaetani Antonio Illiano Umberto Mariani Olga Ragusa John Welle Stefano Boselli, Webmaster PSA The official publication of the Pirandello Society of America Subscriptions: Annual calendar year subscriptions/dues: $35 individual; $50 libraries; $15 students with copy of current ID. International memberships, add $10. Please see Membership form in this issue, or online: www.pirandellosocietyofamerica.org Make all checks payable to: The Pirandello Society of America/PSA c/o Casa Italiana Zerilli-Marimò 24 West 12th Street New York, NY 10011 All correspondence may be sent to the above address. Submissions: All manuscripts will be screened in a peer-review process by at least two readers. Submit with a separate cover sheet giving the author’s name and contact information. Omit self-identifying information in the body of the text and all headers and footers. Guidelines: Please use the current MLA Style Manual; use in-text references, minimal endnotes, works cited. Articles should generally be 10-20 pages in length; reviews, 2-3 pages. Please do not use automatic formatting. Send MSWord doc. -

Il Cinema Di Angelo Musco

ORTO BOTANICO e CINEFORUM DON ORIONE di Messina in collaborazione con l’ASSOCIAZIONE ANTONELLO DA MESSINA presentano la 7ª Edizione (2019) del CINEMA IN ORTO Quattro serate presso la Cavea dell’Orto IL CINEMA DI ANGELO MUSCO BIOGRAFIA - Angelo Musco nasce a Catania il 18 dicembre 1872 e muore a Milano il 6 ottobre 1937. Dopo aver esercitato i più umili mestieri, incomincia a lavorare in un Teatrino dell’Opera dei pupi e poi si dà da fare come canzonettista e macchiettista. Si trasferisce a Messina per unirsi alla Compagnia di Peppino Santoro. Nel 1900 rientra a Catania, dove viene scritturato da Giovanni Grasso, assieme al quale dà l’avvio al teatro popolare siciliano. Nel frattempo rafforza i rapporti prima con Nino Martoglio e poi – dopo aver fondato una sua Compagnia – anche con Luigi Pirandello. IL CINEMA - Dopo il film San Giovanni decollato, risalente al 1917 e diretto da Telemaco Ruggeri, su sceneggiatura di Nino Martoglio (da considerarsi irrimediabilmente perduto), l’esperienza cinematografica di Angelo Musco è tutta racchiusa nel periodo 1932-1937, in cui è il protagonista di ben 10 film, quasi tutti trasposizioni cinematografiche dei suoi successi teatrali. IL RAPPORTO CON MESSINA - Si tratta di un legame molto stretto, che affonda le sue radici in tempi lontanissimi, quando egli vi si reca per la prima volta nel 1899, incontrando il “capocomico” Peppino Santoro, che lo fa debuttare nella sua Compagnia con il nomignolo di Piripicchio. Dopo la morte di Santoro, Musco rientra a Catania; ma Messina gli rimane sempre nel cuore, tanto che vi ritorna diverse volte, anche quando - divenuto famoso - fa Compagnia a sé. -

Pirandello Proto-Modern: a New Reading of <I>L'esclusa</I>

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2017 Pirandello Proto-Modern: A New Reading of L’Esclusa Bradford Masoni The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2330 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] PIRANDELLO PROTO-MODERN: A NEW READING OF L’ESCLUSA by Bradford A. Masoni A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York. 2017 © 2017 BRADFORD A. MASONI All Rights Reserved ii Pirandello Proto-Modern: A New Reading of L’Esclusa by Bradford A. Masoni This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ____________________ ________________________________ Date Paolo Fasoli Chair of Examining Committee ____________________ _____________________________ Date Giancarlo Lombardi Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Paolo Fasoli Giancarlo Lombardi William Coleman THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Pirandello Proto-Modern: A New Reading of L’Esclusa by Bradford A. Masoni Advisor: Paolo Fasoli Luigi Pirandello’s first novel, L’Esclusa, written in 1893, but not published in its definitive edition until 1927, straddles two literary worlds: that of the realistic style of the Italian veristi, and something new, a style and approach to narrative that anticipates the theory of writing Pirandello lays out in his long essay L’Umorismo, as well as the kinds of experimental writing that one associates with early-20th-century modernism in general, and with Pirandello’s later work in particular. -

A Protocol for the Inflected Construction in Sicilian Dialects

Annali di Ca’ Foscari. Serie occidentale ISSN 2499-1562 Vol. 49 – Settembre 2015 A Protocol for the Inflected Construction in Sicilian Dialects Vincenzo Nicolò Di Caro, Giuliana Giusti (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Abstract Most Sicilian dialects display a monoclausal construction with a functional verb (usually of motion), followed by the linking element a and a lexical verb called Inflected Construction by Cardinaletti, Giusti (2001, 2003). This construction shows a high degree of cross-linguistic variation. The aim of the paper is to propose the protocols in the sense of Giusti, Zegrean (2015) to conduct fieldwork in this area. Protocol Linguistics is a metamodel of linguistic research that can be shared by linguists of different theoretical persuasion, can be accessible to non-linguists, and is meant to interface with a number of disciplines and environments such as social sciences and political planning, neuro-psychology and language rehabilitation, pedagogy and language education. The protocols consist of simple table-charts with the horizontal axis listing the empirical environments to be searched, e.g. the languages to be compared, and the vertical axis listing (clusters of) properties, named features, to be valued as +/- according to whether they are present or absent in each environ- ment. The features relevant to the investigation on the Inflected Construction rely on preliminary work by Di Caro (2015), which highlights a finer grained variation than the one presented in previous literature (a.o. Cardinaletti, Giusti 2001, 2003, and Cruschina 2013). In the spirit of the principles-and- parameters approach, the protocols for the Inflected Construction are clustered around two main dimensions, each involving clusters of properties: (i) the lexical restrictions on the functional and/ or the lexical verb; (ii) the person, tense and mood restrictions of the verbal paradigm. -

Arthur Livingston

Arthur Livingston: An Inventory of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Livingston, Arthur, 1883-1944 Title: Arthur Livingston Papers Inclusive Dates: 1494-1986 Extent: 22 document boxes, 3 galley folders, 1 oversize folder (9.16 linear feet) Access: Open for research Administrative Information Acquisition: Gift, 1950 Processed by: Robert Kendrick, Chip Cheek, Elizabeth Murray, Nov. 1996-June 1997 Repository: Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center The University of Texas at Austin Livingston, Arthur, 1883-1944 Biographical Sketch Arthur Livingston, professor of Romance languages and literatures, publisher, and translator, was born on September 30, 1883, in Northbridge, Massachusetts. Livingston earned the A. B. degree at Amherst College in 1904, continuing his work in Romance languages at Columbia University, where he received the Ph. D. in 1911. His teaching positions included an instructorship in Italian at Smith College (1908-1909), an associate professorship in Italian at Cornell University, where Livingston also supervised the Petrarch Catalogue (1910-1911), and an associate professorship in Romance Languages at Columbia University (1911-1917). Among the various honors bestowed upon Livingston were membership in Phi Beta Kappa and the Venetian academic society, the Reale deputazione veneta di storia patria; he was also decorated as a Cavalier of the Crown of Italy. Livingston's desire to disseminate the work of leading European writers and thinkers in the United States led him to an editorship with the Foreign Press Bureau of the Committee on Public Information during World War I. When the war ended, Livingston, in partnership with Paul Kennaday and Ernest Poole, continued his efforts on behalf of foreign literature by founding the Foreign Press Service, an agency that represented foreign authors in English-language markets. -

Contributors

Joseph A. Amato is a retired Minnesota history professor and dean for the Center for Rural and Regional Studies. Covering a variety of subjects and in diverse genres, Amato’s works include When Father and Son Conspire: A Minnesota Farm Murder, The Great Jerusalem Artichoke Circus, Victims and Values, Dust: A History of the Small and Invisible, On Foot: A History of Walking, Surfaces: A History, and forthcoming this year The Book of Twos. He describes his mixed Sicilian inheritance in Jacob’s Well: A Guide to Writing Family History and Coal Cousins: Ruysn and Sicilian Stories and Pennsylvania Anthracite Histories. He recently published his first volume of poetry, Buoyancies: A Ballast Master’s Log and this is his first published short story. Olivia Arieti, a US citizen, has a degree from the University of Pisa and lives in Torre del Lago Puccini, Italy with her family. Besides being a playwright, she loves writing poems and short stories that have appeared in several magazines and anthologies in the USA and the UK. Irene Backalenick has been a working journalist for many years, writing for The New York Times and other national publications. In more recent years, she acquired a Ph. D in theater history and became a theater critic. Now, at age 93, she has turned to a new genre — poetry. Gary Beck has spent most of his adult life as a theater director. He has 11 published chapbooks. His poetry collections include: Days of Destruction (Skive Press), Expectations (Rogue Scholars Press). Dawn in Cities, Assault on Nature, Songs of a Clerk, Civilized Ways (Winter Goose Publishing). -

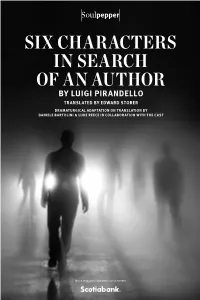

Six Characters in Search of an Author

SIX CHARACTERS IN SEARCH OF AN AUTHOR BY LUIGI PIRANDELLO TRANSLATED BY EDWARD STORER DRAMATURGICAL ADAPTATION ON TRANSLATION BY DANIELE BARTOLINI & LUKE REECE IN COLLABORATION WITH THE CAST major sponsor & community access partner WELCOME TO SIX CHARACTERS IN SEARCH OF AN AUTHOR The artists and staff of Soulpepper and the Young Centre for the Performing Arts acknowledge the original caretakers and storytellers of this land – the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, and Wendat First Nation, and The Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation who are part of the Anishinaabe Nation. We commit to honouring and celebrating their past, present and future. “All around the world and throughout history, humans have acted out the stories that are significant to them, the stories that are central to their sense of who they are, the stories that have defined their communities, and shaped their societies. When we talk about classical theatre we want to explore what that means from the many perspectives of this city. This is a celebration of our global canon.” – Weyni Mengesha, Soulpepper’s Artistic Director photo by Emma Mcintyre Partners & Supporters James O’Sullivan & Lucie Valée Karrin Powys-Lybbe & Chris von Boetticher Sylvia Soyka Kathleen & Bill Troost 2 CAST & CREATIVE TEAM Cast Beatriz Pizano Moya O’Connell Tom Rooney The Mother Leading Lady Leading Man Diego Matamoros Gregory Prest The Manager The Prompter, Stage Manager, The Son Hannah Miller Anand Rajaram The Stepdaughter The Father Creative Team Daniele Bartolini Gregory Sinclair Mimi Warshaw Director -

Pirandello : Six Characters in Search of an Author

Strictly for Private Use Course Material Department of English and Modern European Languages M.A. SEMESTER IV S M Mirza Paper-XIV(C) : Comparative Literature Unit IV : Drama Aristophanes : The Frogs Shudrak : Mrichchakatikam (The Clay Cart) Moliere : The Miser Luigi Pirandello : Six Characters in Search of an Author Dear Students, Hello. Only the text highlighted above remains to be taught in UNIT IV. I’m providing you course material below for Luigi Pirandello: Six Characters in Search of an Author so that you can understand it and prepare your answers for the exam. Prepare the following: critical appreciation, themes, technique, innovations, and significance of the title (short question). I’ll send you course material on Unit I soon. In case you have any doubts you can contact me on phone or send queries to my email. All the best! Luigi Pirandello: Six Characters in Search of an Author Biographical note Luigi Pirandello(1867-1936) was born in Girgenti, Sicily. He studied philology at Rome and at Bonn and wrote a dissertation on the dialect of his native town (1891). From 1897 to 1922 he was professor of aesthetics and stylistics at the Real Istituto di Magistere Femminile at Rome. Pirandello’s work is impressive by its sheer volume. He wrote a great number of novellas which were collected under the title Novelle per un anno (15 vols., 1922-37). Of his six novels the best known are Il fu Mattia Pascal (1904) [The Late Mattia Pascal], I vecchi e i giovani (1913) [The Old and the Young], Si gira (1916) | [Shoot!], and Uno, nessuno e centomila (1926) [One, None, and a Hundred thousand].