AI Ignition Ignite Your AI Curiosity with Roz Picard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CITY MOOD How Does Your City Feel?

CITY MOOD how does your city feel? Luisa Fabrizi Interaction Design One year Master 15 Credits Master Thesis August 2014 Supervisor: Jörn Messeter CITY MOOD how does your city feel? 2 Thesis Project I Interaction Design Master 2014 Malmö University Luisa Fabrizi [email protected] 3 01. INDEX 01. INDEX .................................................................................................................................03 02. ABSTRACT ...............................................................................................................................04 03. INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................................................05 04. METHODOLOGY ..............................................................................................................................08 05. THEORETICAL FRamEWORK ...........................................................................................................09 06. DESIGN PROCESS ...................................................................................................................18 07. GENERAL CONCLUSIONS ..............................................................................................................41 08. FURTHER IMPLEMENTATIONS ....................................................................................................44 09. APPENDIX ..............................................................................................................................47 02. -

Playing God? Towards Machines That Deny Their Maker

Lecture with Prof. Rosalind Picard, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Playing God? Towards Machines that Deny Their Maker 22. April 2016 14:15 UniS, Hörsaal A003 CAMPUS live VBG Bern Institut für Philosophie Christlicher Studentenverein Christliche Hochschulgruppe Länggassstrasse 49a www.campuslive.ch/bern www.bern.vbg.net 3000 Bern 9 www.philosophie.unibe.ch 22. April 2016 14:15 UniS, Hörsaal A003 (Schanzeneckstrasse 1, Bern) Lecture with Prof. Rosalind Picard (MIT) Playing God? Towards Machines that Deny their Maker "Today, technology is acquiring the capability to sense and respond skilfully to human emotion, and in some cases to act as if it has emotional processes that make it more intelligent. I'll give examples of the potential for good with this technology in helping people with autism, epilepsy, and mental health challenges such as anxie- ty and depression. However, the possibilities are much larger: A few scientists want to build computers that are vastly superior to humans, capable of powers beyond reproducing their own kind. What do we want to see built? And, how might we make sure that new affective technologies make human lives better?" Professor Rosalind W. Picard, Sc.D., is founder and director of the Affective Computing Research Group at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Media Lab where she also chairs MIT's Mind+Hand+Heart initiative. Picard has co- founded two businesses, Empatica, Inc. creating wearable sensors and analytics to improve health, and Affectiva, Inc. delivering software to measure and communi- cate emotion through facial expression analysis. She has authored or co-authored over 200 scientific articles, together with the book Affective Computing, which was instrumental in giving rise to the field by that name. -

Membership Information

ACM 1515 Broadway New York, NY 10036-5701 USA The CHI 2002 Conference is sponsored by ACM’s Special Int e r est Group on Computer-Human Int e r a c t i o n (A CM SIGCHI). ACM, the Association for Computing Machinery, is a major force in advancing the skills and knowledge of Information Technology (IT) profession- als and students throughout the world. ACM serves as an umbrella organization offering its 78,000 members a variety of forums in order to fulfill its members’ needs, the delivery of cutting-edge technical informa- tion, the transfer of ideas from theory to practice, and opportunities for information exchange. Providing high quality products and services, world-class journals and magazines; dynamic special interest groups; numerous “main event” conferences; tutorials; workshops; local special interest groups and chapters; and electronic forums, ACM is the resource for lifelong learning in the rapidly changing IT field. The scope of SIGCHI consists of the study of the human-computer interaction process and includes research, design, development, and evaluation efforts for interactive computer systems. The focus of SIGCHI is on how people communicate and interact with a broadly-defined range of computer systems. SIGCHI serves as a forum for the exchange of ideas among com- puter scientists, human factors scientists, psychologists, social scientists, system designers, and end users. Over 4,500 professionals work together toward common goals and objectives. Membership Information Sponsored by ACM’s Special Interest Group on Computer-Human -

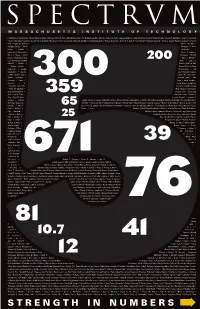

Download a PDF of This Issue

Hal Abelson • Edward Adams • Morris Adelman • Edward Adelson • Khurram Afridi • Anuradha Agarwal • Alfredo Alexander-Katz • Marilyne Andersen • Polina Olegovna Anikeeva • Anuradha M Annaswamy • Timothy Antaya • George E. Apostolakis • Robert C. Armstrong • Elaine V. Backman • Lawrence Bacow • Emilio Baglietto • Hari Balakrishnan • Marc Baldo • Ronald G. Ballinger • George Barbastathis • William A. Barletta • Steven R. H. Barrett • Paul I. Barton • Moungi G. Bawendi • Martin Z. Bazant • Geoffrey S. Beach • Janos M. Beer • Angela M. Belcher • Moshe Ben-Akiva • Hansjoerg Berger • Karl K. Berggren • A. Nihat Berker • Dimitri P. Bertsekas • Edmundo D. Blankschtein • Duane S. Boning • Mary C. Boyce • Kirkor Bozdogan • Richard D. Braatz • Rafael Luis Bras • John G. Brisson • Leslie Bromberg • Elizabeth Bruce • Joan E. Bubluski • Markus J. Buehler • Cullen R. Buie • Vladimir Bulovic • Mayank Bulsara • Tonio Buonassisi • Jacopo Buongiorno • Oral Buyukozturk • Jianshu Cao • Christopher Caplice • JoAnn Carmin • John S. Carroll • W. Craig Carter • Frederic Casalegno • Gerbrand Ceder • Ivan Celanovic • Sylvia T. Ceyer • Ismail Chabini • Anantha • P. Chandrakasan • Gang Chen • Sow-Hsin Chen • Wai K. Cheng • Yet-Ming Chiang • Sallie W. Chisholm • Nazil Choucri • Chryssosto- midis Chryssostomos • Shaoyan Chu • Jung-Hoon Chun • Joel P. Clark • Robert E. Cohen • Daniel R. Cohn • Clark K. Colton • Patricia Connell • Stephen R. Connors • Chathan Cooke • Charles L. Cooney • Edward F. Crawley • Mary Cummings • Christopher C. Cummins • Kenneth R. Czerwinski • Munther A. Da hleh • Rick Lane Danheiser • Ming Dao • Richard de Neufville • Olivier L de Weck • Edward Francis DeLong • Erik Demaine • Martin Demaine • Laurent Demanet • Michael J. Demkowicz • John M. Deutch • Srini Devadas • Mircea Dinca • Patrick S Doyle • Elisabeth M.Drake • Mark Drela • Catherine L.Drennan • Michael J.Driscoll • Steven Dubowsky • Esther Duflo • Fredo Durand • Thomas Eagar • Richard S. -

Wearable Platform to Foster Learning of Natural Facial Expressions and Emotions in High-Functioning Autism and Asperger Syndrome

Wearable Platform to Foster Learning of Natural Facial Expressions and Emotions in High-Functioning Autism and Asperger Syndrome PRIMARY INVESTIGATORS: Matthew Goodwin, The Groden Center. Rosalind Picard, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Media Laboratory Rana el Kaliouby, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Media Laboratory Alea Teeters, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Media Laboratory June Groden, The Groden Center DESCRIPTION: Evaluate the scientific and clinical significance of using a wearable camera system (Self-Cam) to improve recognition of emotions from real-world faces in young adults with Asperger syndrome (AS) and high-functioning autism (HFA). The study tests a group of 10 young adults diagnosed with AS/HFA who are asked to wear Self-Cam three times a week for 10 weeks, and use a computerized, interactive facial expression analysis system to review and analyze their videos on a weekly basis. A second group of 10 age-, sex-, IQ-matched young adults with AS/HFA will use Mind Reading – a systematic DVD guide for teaching emotion recognition. These two groups will be tested pre- and post-intervention on recognition of emotion from faces at three levels of generalization: videos of themselves, videos of their interaction partner, and videos of other participants (i.e. people they are less familiar with). A control group of 10 age- and sex- matched typically developing adults will also be tested to establish performance differences in emotion recognition abilities across groups. This study will use a combination of behavioral reports, direct observation, and pre- and post- questionnaires to assess Self-Cam’s acceptance by persons with autism. We hypothesize that the typically developing control group will perform better on emotion recognition than both groups with AS/HFA at baseline and that the Self-Cam group, whose intervention teaches emotion recognition using real-life videos, will perform better than the Mind Reading group who will learn emotion recognition from a standard stock of emotion videos. -

Research Article Multimodal Affective Computing to Enhance the User Experience of Educational Software Applications

Hindawi Mobile Information Systems Volume 2018, Article ID 8751426, 10 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/8751426 Research Article Multimodal Affective Computing to Enhance the User Experience of Educational Software Applications Jose Maria Garcia-Garcia ,1 Vı´ctor M. R. Penichet ,1 Marı´a Dolores Lozano ,1 Juan Enrique Garrido ,2 and Effie Lai-Chong Law3 1Research Institute of Informatics, University of Castilla-La Mancha, Albacete, Spain 2Escuela Polite´cnica Superior, University of Lleida, Lleida, Spain 3Department of Informatics, University of Leicester, Leicester, UK Correspondence should be addressed to Mar´ıa Dolores Lozano; [email protected] Received 19 January 2018; Revised 8 July 2018; Accepted 5 August 2018; Published 13 September 2018 Academic Editor: Salvatore Carta Copyright © 2018 Jose Maria Garcia-Garcia et al. -is is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Affective computing is becoming more and more important as it enables to extend the possibilities of computing technologies by incorporating emotions. In fact, the detection of users’ emotions has become one of the most important aspects regarding Affective Computing. In this paper, we present an educational software application that incorporates affective computing by detecting the users’ emotional states to adapt its behaviour to the emotions sensed. -is way, we aim at increasing users’ engagement to keep them motivated for longer periods of time, thus improving their learning progress. To prove this, the application has been assessed with real users. -e performance of a set of users using the proposed system has been compared with a control group that used the same system without implementing emotion detection. -

Total Affect Control. Or

Total Affect Control Or: Who’s Afraid of a Pleasing Little Sister? Marie-Luise Angerer and Bernd Bösel Abstract Through the emergence of affect- and psychotechnologies, especially with the advent of affective computing, the recognition, regulation and production of affects have been automatised to an unforesee- able degree. The roots of this algorithmic automation can be seen in the propagation of cybernetic models in the field of psychology from the 1950s onwards. A direct genealogical line leads from Silvan Tomkins’ affect system via Paul Ekman’s facial emotion recogni- tion to Rosalind Picard’s conception and co-development of affect- sensitive computer systems. Nevertheless, the implicated aspects of surveillance and collection of affective information have yet to be assessed critically. Such an assessment is outlined here. The Tip of the Iceberg of Digital Control: Affective Computing As discussed in many recent publications, the regulation of affects and emotions is dependent on historical, cultural, socio-political and not least media-tech- nological developments.1 How affects and emotions are coded and expressed, whether they are fostered and actively supported or whether they are ignored or even denied, depends on a wealth of factors that are dealt with individually by many scholars in the fields of history and cultural studies.2 Today, however, a fundamental shift is taking place in the conditions of media technology (a shift whose socio-political impact is still entirely unclear) as affectivity is technicised 1 See for example: Angerer/Bösel/Ott (2014); Goldberg (2012); Wetherell (2012); Dixon (2003). 2 We deliberately use both terms here to point out that in the discourses in question no distinction between affect and emotion is made. -

Exploratory Tool for Autism Spectrum Conditions

MIT | Media Lab | Affective Computing Exploratory Tool for Autism Spectrum Conditions Rana el Kaliouby Alea Teeters Rosalind Picard http://www.media.mit.edu/affect BSN 2006 Workshop Autism Spectrum Conditions autism mind-reading machines demo challenges Center for Disease Control and Prevention (2005) – 1 child in 166 has ASC {kaliouby, teeters, picard}@media.mit.edu MIT | Media Lab | Affective Computing New Initiative: Autism Wearables autism mind-reading machines demo challenges Repetitive, obsessive behavior Related work • Monitoring • Assessment • Natural environment Communication Social interaction {kaliouby, teeters, picard}@media.mit.edu MIT | Media Lab | Affective Computing Examples of Autism Wearables autism mind-reading machines demo challenges Automated capture to support therapists Recognition of stimming behavior during intervention sessions (e.g. flapping, rocking) (Digital Pen, Voice Input and Video) Bluetooth accelerator and HMMs Kientz, Broing, Abowd, Hayes Westeyn, Vadas, Bian, Starner, (Ubicomp 2005) and Abowd (ISWC 2005) {kaliouby, teeters, picard}@media.mit.edu MIT | Media Lab | Affective Computing Autism Spectrum Conditions autism mind-reading machines demo challenges Repetitive, obsessive behavior Communication Social interaction Our research • Intervention • Assistive • Natural environment {kaliouby, teeters, picard}@media.mit.edu MIT | Media Lab | Affective Computing Mind-Read > Act > Persuade autism mind-reading machines demo challenges hmm … Roz looks busy. Its probably not a good time to bring this up Analysis -

Affectiva-MIT Facial Expression Dataset (AM-FED): Naturalistic and Spontaneous Facial Expressions Collected In-The-Wild

Affectiva-MIT Facial Expression Dataset (AM-FED): Naturalistic and Spontaneous Facial Expressions Collected In-the-Wild The MIT Faculty has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Citation McDuff, Daniel Jonathan; el Kaliouby, Rana; Senechal, Thibaud; Amr, May; Cohn, Jeffrey F.; Picard, Rosalind W. " Affectiva-MIT Facial Expression Dataset (AM-FED): Naturalistic and Spontaneous Facial Expressions Collected In-the-Wild." Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), 2013. Publisher Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) Version Author's final manuscript Citable link http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/80733 Terms of Use Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Detailed Terms http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ Affectiva-MIT Facial Expression Dataset (AM-FED): Naturalistic and Spontaneous Facial Expressions Collected In-the-Wild Daniel McDuffyz, Rana El Kalioubyyz, Thibaud Senechalz, May Amrz, Jeffrey F. Cohnx, Rosalind Picardyz z Affectiva Inc., Waltham, MA, USA y MIT Media Lab, Cambridge, MA, USA x Robotics Institute, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA, USA [email protected], fkaliouby,thibaud.senechal,[email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract ing research and media testing [14] to understanding non- verbal communication [19]. With the ubiquity of cameras Computer classification of facial expressions requires on computers and mobile devices, there is growing interest large amounts of data and this data needs to reflect the in bringing these applications to the real-world. To do so, diversity of conditions seen in real applications. -

Affective Computing

The IEEE Global Initiative on Ethics of Autonomous and Intelligent Systems Affective Computing Affect is a core aspect of intelligence. Drives and emotions, such as excitement and depression, are used to coordinate action throughout intelligent life, even in species that lack a nervous system. Emotions are one mechanism that humans evolved to accomplish what needs to be done in the time available with the information at hand—to satisfice. Emotions are not an impediment to rationality; arguably they are integral to rationality in humans. Humans create and respond to both positive and negative emotional influence as they coordinate their actions with other individuals to create societies. Autonomous and intelligent systems (A/IS) are being designed to simulate emotions in their interactions with humans in ways that will alter our societies. A/IS should be used to help humanity to the greatest extent possible in as many contexts as are appropriate. While A/IS have tremendous potential to effect positive change, there is also potential that artifacts used in society could cause harm either by amplifying, altering, or even dampening human emotional experience. Even rudimentary versions of synthetic emotions, such as those already in use within nudging systems, have already altered the perception of A/IS by the general public and public policy makers. This chapter of Ethically Aligned Design addresses issues related to emotions and emotion- like control in interactions between humans and design of A/IS. We have put forward recommendations on a variety of topics: considering how affect varies across human cultures; the particular problems of artifacts designed for caring and private relationships; considerations of how intelligent artifacts may be used for “nudging”; how systems can support human flourishing; and appropriate policy interventions for artifacts designed with inbuilt affective systems. -

Project Summary Exploring the Role of Emotion in Propelling the SMET

Project Summary Exploring the Role of Emotion in Propelling the SMET Learning Process Rosalind Picard, Barry Kort, Rob Reilly Media Laboratory, M.I.T. {picard, bkort, reilly}@media.mit.edu The current educational system is constructed so as to emphasize the evolution of rule-based reasoners (students who understand the ‘what’ of a task/problem). However scientists, mathematicians, engineers, and technologists are not rule-based reasoners. They are model-based reasoners/thinkers (e.g., they do recursion, diagnostic reasoning, cognitive assessment, cognitive appraisal). To provide for the development of SMET (science, math, engineering, technology) learners, teachers and mentors who are reflective of the educational system’s pedagogy must not model directive teaching, which develops rule-based thinkers, but they should model how to learn. The educational pedagogy of a teacher and of the curriculum must include an understanding of learning intelligence-the ability to understand and model how-to-learn, how to solve a unique problem even when confronted with discouraging set- backs during its solution; in other words, they must be able to do model-based reasoning. Based upon this hypothesis, we propose to explore and evolve current educational pedagogy such that SMET learning will move toward a model-based reasoning pedagogy. There has been a good deal of researcher conducted in this field that is very important. Their focus, however, is largely on how mood influences the content of what is learned or retrieved, and very much in a rule-based learning context. Our focus, in contrast, is on constructing a theory of affect in SMET learning, together with building practical tools that can specifically aid the student learn how to learn. -

The Power of Targeted Prayer How Are You Doing?

FRONTLINES A Window into America’s Universities APRIL 2020 Faculty Commons® A CRU MINISTRY §1 – How are you doing? The Power of A Tentmaking Not Falling Targeted Prayer Professor Through Cracks Eliciting hope and bringing comfort in the How God specifically set the stage to develop Cal Poly professor helps others live out their We want every grad student to have the ravages of a pandemic. §1 a thriving faculty ministry at NC State. §2 faith in academia and business. §3 opportunity to know Jesus. §4 How are you doing? Rick Hove, Faculty Commons® National Director to each other, “Aren’t we glad to be home!” As I On March 5 write this, our Israel/Italy trip is so far from my Sonya and I mind. A dear friend with Cru struggles to live. My Duke doctor/professor friend suits up in planned to hazmat gear to care for those with the disease. COVID-19 has rocked our world, leaving our leave with mouths agape, wondering in disbelief how this could be, and speculating what will be. So, like three other a daffodil emerging in spring after a deep freeze, anything emerging these days as couples for an extended “certain,” “reliable,” or “comforting” becomes trip to Israel, which would cherished indeed. One thing that has emerged as certain, re- culminate with a visit to our Faculty Com- liable, and comforting is that we need each mons work in Italy. One of our traveling other. From the moment normal life began friends is an infectious disease doctor/profes- to unravel, I sensed the Lord encouraging me Reimagining Ministry sor at Duke, who obviously kept a watchful eye to ask folks, “How are you doing? How is this Faculty Commons has been reimagining what ministry looks like given social distancing on this new virus across the globe.