Notes on Nests and Behavior of the Hawaiian Crowl P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alalā Or Hawaiian Crow (Corvus Hawaiiensis) 5-Year

`Alalā or Hawaiian Crow (Corvus hawaiiensis) 5-Year Review Summary and Evaluation U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Pacific Islands Fish and Wildlife Office Honolulu, Hawai`i 5-YEAR REVIEW Species reviewed: `Alalā or Hawaiian Crow (Corvus hawaiiensis) TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 GENERAL INFORMATION .......................................................................................... 1 1.1 Reviewers ....................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Methodology used to complete the review: ................................................................. 1 1.3 Background ................................................................................................................... 1 2.0 REVIEW ANALYSIS ....................................................................................................... 2 2.1 Application of the 1996 Distinct Population Segment (DPS) policy ......................... 2 2.2 Recovery Criteria .......................................................................................................... 3 2.3 Updated Information and Current Species Status .................................................... 4 2.4 Synthesis......................................................................................................................... 9 3.0 RESULTS .......................................................................................................................... 9 3.1 Recommended Classification ...................................................................................... -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 74/Thursday, April 16, 2020/Rules

21282 Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 74 / Thursday, April 16, 2020 / Rules and Regulations DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR United States and the Government of United States or U.S. territories as a Canada Amending the 1916 Convention result of recent taxonomic changes; Fish and Wildlife Service between the United Kingdom and the (8) Change the common (English) United States of America for the names of 43 species to conform to 50 CFR Part 10 Protection of Migratory Birds, Sen. accepted use; and (9) Change the scientific names of 135 [Docket No. FWS–HQ–MB–2018–0047; Treaty Doc. 104–28 (December 14, FXMB 12320900000//201//FF09M29000] 1995); species to conform to accepted use. (2) Mexico: Convention between the The List of Migratory Birds (50 CFR RIN 1018–BC67 United States and Mexico for the 10.13) was last revised on November 1, Protection of Migratory Birds and Game 2013 (78 FR 65844). The amendments in General Provisions; Revised List of this rule were necessitated by nine Migratory Birds Mammals, February 7, 1936, 50 Stat. 1311 (T.S. No. 912), as amended by published supplements to the 7th (1998) AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, Protocol with Mexico amending edition of the American Ornithologists’ Interior. Convention for Protection of Migratory Union (AOU, now recognized as the American Ornithological Society (AOS)) ACTION: Final rule. Birds and Game Mammals, Sen. Treaty Doc. 105–26 (May 5, 1997); Check-list of North American Birds (AOU 2011, AOU 2012, AOU 2013, SUMMARY: We, the U.S. Fish and (3) Japan: Convention between the AOU 2014, AOU 2015, AOU 2016, AOS Wildlife Service (Service), revise the Government of the United States of 2017, AOS 2018, and AOS 2019) and List of Migratory Birds protected by the America and the Government of Japan the 2017 publication of the Clements Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA) by for the Protection of Migratory Birds and Checklist of Birds of the World both adding and removing species. -

Appendix, French Names, Supplement

685 APPENDIX Part 1. Speciesreported from the A.O.U. Check-list area with insufficient evidencefor placementon the main list. Specieson this list havebeen reported (published) as occurring in the geographicarea coveredby this Check-list.However, their occurrenceis considered hypotheticalfor one of more of the following reasons: 1. Physicalevidence for their presence(e.g., specimen,photograph, video-tape, audio- recording)is lacking,of disputedorigin, or unknown.See the Prefacefor furtherdiscussion. 2. The naturaloccurrence (unrestrained by humans)of the speciesis disputed. 3. An introducedpopulation has failed to becomeestablished. 4. Inclusionin previouseditions of the Check-listwas basedexclusively on recordsfrom Greenland, which is now outside the A.O.U. Check-list area. Phoebastria irrorata (Salvin). Waved Albatross. Diornedeairrorata Salvin, 1883, Proc. Zool. Soc. London, p. 430. (Callao Bay, Peru.) This speciesbreeds on Hood Island in the Galapagosand on Isla de la Plata off Ecuador, and rangesat seaalong the coastsof Ecuadorand Peru. A specimenwas takenjust outside the North American area at Octavia Rocks, Colombia, near the Panama-Colombiaboundary (8 March 1941, R. C. Murphy). There are sight reportsfrom Panama,west of Pitias Bay, Dari6n, 26 February1941 (Ridgely 1976), and southwestof the Pearl Islands,27 September 1964. Also known as GalapagosAlbatross. ThalassarchechrysosWma (Forster). Gray-headed Albatross. Diornedeachrysostorna J. R. Forster,1785, M6m. Math. Phys. Acad. Sci. Paris 10: 571, pl. 14. (voisinagedu cerclepolaire antarctique & dansl'Ocean Pacifique= Isla de los Estados[= StatenIsland], off Tierra del Fuego.) This speciesbreeds on islandsoff CapeHorn, in the SouthAtlantic, in the southernIndian Ocean,and off New Zealand.Reports from Oregon(mouth of the ColumbiaRiver), California (coastnear Golden Gate), and Panama(Bay of Chiriqu0 are unsatisfactory(see A.O.U. -

Alpha Codes for 2154 Bird Species (And 108 Non-Species Taxa) in Accordance with the 60Th AOU Supplement (2019), Sorted Alphabetically by English Name

Four-letter (English Name) and Six-letter (Scientific Name) Alpha Codes for 2154 Bird Species (and 108 Non-Species Taxa) in accordance with the 60th AOU Supplement (2019), sorted alphabetically by English name Prepared by Peter Pyle and David F. DeSante The Institute for Bird Populations www.birdpop.org ENGLISH NAME 4-LETTER CODE SCIENTIFIC NAME 6-LETTER CODE Abert's Towhee ABTO Melozone aberti MELABE Acadian Flycatcher ACFL Empidonax virescens EMPVIR Acorn Woodpecker ACWO Melanerpes formicivorus MELFOR Adelaide's Warbler ADWA Setophaga adelaidae SETADE African Collared-Dove AFCD Streptopelia roseogrisea STRROS African Silverbill AFSI Euodice cantans EUOCAN Agami Heron AGHE Agamia agami AGAAGA Ainley's Storm-Petrel AISP Hydrobates cheimomnestes HYDCHE Akekee AKEK Loxops caeruleirostris LOXCAE Akiapolaau AKIA Hemignathus wilsoni HEMWIL Akikiki AKIK Oreomystis bairdi OREBAI Akohekohe AKOH Palmeria dolei PALDOL Alder Flycatcher ALFL Empidonax alnorum EMPALN + Aleutian Cackling Goose ACGO Branta hutchinsii leucopareia BRAHLE Aleutian Tern ALTE Onychoprion aleuticus ONYALE Allen's Hummingbird ALHU Selasphorus sasin SELSAS Alpine Swift ALSW Apus melba APUMEL Altamira Oriole ALOR Icterus gularis ICTGUL Altamira Yellowthroat ALYE Geothlypis flavovelata GEOFLA Amaui AMAU Myadestes woahensis MYAWOA Amazon Kingfisher AMKI Chloroceryle amazona CHLAMA American Avocet AMAV Recurvirostra americana RECAME American Bittern AMBI Botaurus lentiginosus BOTLEN American Black Duck ABDU Anas rubripes ANARUB + American Black Duck X Mallard Hybrid ABMH* Anas -

Seed Dispersal by a Captive Corvid: the Role of the 'Alala¯ (Corvus

Ecological Applications, 22(6), 2012, pp. 1718–1732 Ó 2012 by the Ecological Society of America Seed dispersal by a captive corvid: the role of the ‘Alala¯ (Corvus hawaiiensis) in shaping Hawai‘i’s plant communities 1,4 1 2 1,3 SUSAN CULLINEY, LIBA PEJCHAR, RICHARD SWITZER, AND VIVIANA RUIZ-GUTIERREZ 1Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Conservation Biology, Colorado State University, 1474 Campus Delivery, Fort Collins, Colorado 80523 USA 2Hawai‘i Endangered Bird Conservation Program, San Diego Zoo Institute for Conservation Research, Volcano, Hawaii 96785 USA 3Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, 159 Sapsucker Woods Road, Cornell University, Ithaca, NewYork 14850 USA Abstract. Species loss can lead to cascading effects on communities, including the disruption of ecological processes such as seed dispersal. The endangered ‘Alala¯ (Corvus hawaiiensis), the largest remaining species of native Hawaiian forest bird, was once common in mesic and dry forests on the Big Island of Hawai‘i, but today it exists solely in captivity. Prior to its extinction in the wild, the ‘Alala¯ may have helped to establish and maintain native Hawaiian forest communities by dispersing seeds of a wide variety of native plants. In the absence of ‘Alala¯, the structure and composition of Hawai‘i’s forests may be changing, and some large-fruited plants may be dispersal limited, persisting primarily as ecological anachronisms. We fed captive ‘Alala¯ a variety of native fruits, documented behaviors relating to seed dispersal, and measured the germination success of seeds that passed through the gut of ‘Alala¯ relative to the germination success of seeds in control groups. ‘Alala¯ ate and carried 14 native fruits and provided germination benefits to several species by ingesting their seeds. -

Times to Extinction for Small Populations of Large Birds (Crow/Owl/Hawk/Population Lifetime/Population Size) STUART L

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 90, pp. 10871-10875, November 1993 Population Biology Times to extinction for small populations of large birds (crow/owl/hawk/population lifetime/population size) STUART L. PIMM*, JARED DIAMONDt, TIMOTHY M. REEDt, GARETH J. RUSSELL*, AND JARED VERNER§ *Department of Zoology, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN 37996; tDepartment of Physiology, University of California Medical School, Los Angeles, CA 90024-1751; tJoint Nature Conservation Committee, Monkstone House, Peterborough, PE1 1UA, United Kingdom; and §U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Research Station, Fresno, CA 93710 Contributed by Jared Diamond, August 9, 1993 ABSTRACT A major practical problem in conservation such counts. European islands provide the most extensive biology is to predict the survival times-"lifetimes"-for small existing data set, and hence the best surrogates for 'Alala and populations under alternative proposed management regimes. Spotted Owl populations for the foreseeable future. The data Examples in the United States include the 'Alala (Hawaiian consist of counts of nesting birds tabulated in the annual Crow; Corvus hawaiiensis) and Northern Spotted Owl (Strix reports of bird observatories on small islands around the occidentalis caurina). To guide such decisions, we analyze coasts of Britain and Ireland, and on the German North Sea counts of ail crow, owl, and hawk species in the most complete island of Helgoland. Subsets of these data have been ana- available data set: counts of bird breeding pairs on 14 Euro- lyzed previously (2-9). pean islands censused for 29-66 consecutive years. The data set Our paper expands the previously analyzed data set to yielded 129 records for analysis. -

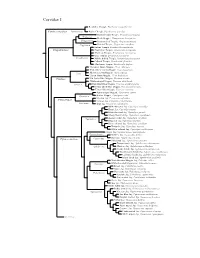

Corvidae Species Tree

Corvidae I Red-billed Chough, Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax Pyrrhocoracinae =Pyrrhocorax Alpine Chough, Pyrrhocorax graculus Ratchet-tailed Treepie, Temnurus temnurus Temnurus Black Magpie, Platysmurus leucopterus Platysmurus Racket-tailed Treepie, Crypsirina temia Crypsirina Hooded Treepie, Crypsirina cucullata Rufous Treepie, Dendrocitta vagabunda Crypsirininae ?Sumatran Treepie, Dendrocitta occipitalis ?Bornean Treepie, Dendrocitta cinerascens Gray Treepie, Dendrocitta formosae Dendrocitta ?White-bellied Treepie, Dendrocitta leucogastra Collared Treepie, Dendrocitta frontalis ?Andaman Treepie, Dendrocitta bayleii ?Common Green-Magpie, Cissa chinensis ?Indochinese Green-Magpie, Cissa hypoleuca Cissa ?Bornean Green-Magpie, Cissa jefferyi ?Javan Green-Magpie, Cissa thalassina Cissinae ?Sri Lanka Blue-Magpie, Urocissa ornata ?White-winged Magpie, Urocissa whiteheadi Urocissa Red-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa erythroryncha Yellow-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa flavirostris Taiwan Blue-Magpie, Urocissa caerulea Azure-winged Magpie, Cyanopica cyanus Cyanopica Iberian Magpie, Cyanopica cooki Siberian Jay, Perisoreus infaustus Perisoreinae Sichuan Jay, Perisoreus internigrans Perisoreus Gray Jay, Perisoreus canadensis White-throated Jay, Cyanolyca mirabilis Dwarf Jay, Cyanolyca nanus Black-throated Jay, Cyanolyca pumilo Silvery-throated Jay, Cyanolyca argentigula Cyanolyca Azure-hooded Jay, Cyanolyca cucullata Beautiful Jay, Cyanolyca pulchra Black-collared Jay, Cyanolyca armillata Turquoise Jay, Cyanolyca turcosa White-collared Jay, Cyanolyca viridicyanus -

Songbird Remix CORVUS CORVUS Contents

Avian Models for 3D Applications by Ken Gilliland 1 Songbird ReMix CORVUS CORVUS Contents Manual Introduction 3 Overview and Use 3 Where to Find your birds and Poses 4 One Folder to Rule them All 4 Physical-based Rendering 5 Posing and Shaping Tips 5 Field Guide Field Guide List 6 Ravens Australian Raven 7 Common Raven 9 White-necked Raven 12 Crows American Crow 14 Eurasian or Western Jackdaw 18 ‘Alala - Hawaiian Crow 21 Rook 25 Credits and Resources 29 Copyrighted 2013-20 by Ken Gilliland www.SongbirdReMix.com Opinions expressed on this booklet are solely that of the author, Ken Gilliland, and may or may not reflect the opinions of the publisher. 2 Songbird ReMix CORVUS CORVUS Introduction Ravens and crows through the ages have represented the darker and sometimes, playful elements in human cultures. In Irish mythology, crows are associated with Morrigan, the goddess of war and death while the Norse believed that ravens carry news to the god Odin about the mortal world. In Hawaiian, Aboriginal and Native American cultures, crows and ravens are believed to be embodiments of ancestor’s spirits or sometimes “The Trickster”; a deity that breaks the rules of the gods or nature, sometimes maliciously but usually with ultimately positive effects. The collective name for a group of crows is a “murder of crows”. Ravens and crows are now considered to be among the world's most intelligent animals. Recent research has found some species capable of not only tool use but also tool construction. The set is located within the Animals : Songbird ReMix folder. -

Songbird Ecology in Southwestern Ponderosa Pine Forests: Forest Service a Literature Review

Songbird Ecology in Southwestern Ponderosa Pine Forests: Forest Service A Literature Review This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. Block, William M.; Finch, Deborah M., technical editors. 1997. Songbird ecology in southwestern ponderosa pine forests: a literature review. Gen. Tech. Rep. RM-GTR-292. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station. 152 p. This publication reviews and synthesizes the literature about ponderosa pine forests of the Southwest, with emphasis on the biology, ecology, and conservation of songbirds. Critical bird-habitat management issues related to succession, snags, old growth, fire, logging, grazing, recreation, and landscape scale are addressed. Overviews of the ecol- ogy, current use, and history of Southwestern ponderosa pine forests are also provided. This report is one of the outcomes of the Silver vs ~hom'ascourt -settlement agreement of 1996. It is intended for planners, scientists, and conservationists in solving some of the controversies over managing forests and birds in the Southwest. Keywords: ponderosa pine, Southwest, songbirds Technical Editors: The order of editorship was determined by coin toss. William M. Block is project leader and research wildlife biologist with the Southwestern Terrestrial Ecosystem research work unit, Southwest Forest Sciences Complex, 2500 S. Pine Knoll, Flagstaff, AZ 86001. Deborah M. Finch is project leader and research wildlife biologist with the Southwestern Grassland and Riparian research work unit, Forestry Sciences Laboratory, 2205 Columbia SE, Albuquerque, NM 87106. Publisher: Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station Fort Collins, Colorado You may order additional copies of this publication by sending your mailing informa- tion in label form through one of the following media. -

Reintroduction of Captive Animals Into Their Native Habitat: a Bibliography

TITLE: REINTRODUCTION OF CAPTIVE ANIMALS INTO THEIR NATIVE HABITAT: A BIBLIOGRAPHY AUTHOR & INSTITUTION: Kay A. Kenyon, Librarian National Zoological Park Branch Smithsonian Institution Libraries Washington, D.C. DATE: September 1988 LAST UPDATE: August 1995 TABLE OF CONTENTS General . 1 Invertebrates . 9 Fish . 11 Reptiles and Amphibians . 13 Birds . 18 Mammals . 35 GENERAL Newsletter: Re-Introduction News. 1990,-- no. 1--. Chairman, RSG: Dr. Mark Stanley Price. Edited by Minoo Rahbar. IUCN/SSC Re-introduction Specialist Group, c/o African Wildlife Foundation, P.O. Box 48177, Nairobi, Kenya. Fax (254)-2-710372; Tel (254)-2-710367. 1968 Petrides, G.A. 1968. Problems in species' introductions. IUCN Bulletin, New Series, 2(7):70-71. 1969 Wayre, P. 1969. The role of zoos in breeding threatened species of mammals and birds in captivity. Biological Conservation, 2(1):47-49. 1977 Brambell, M.R. 1977. Reintroduction. International Zoo Yearbook, 17:112-116. Kear, J. & A.J.Berger. 1977. The problem of breeding endangered species in captivity. International Zoo Yearbook, 17:5-14. Sankhala, K.S. 1977. Captive breeding, reintroduction and nature protection: the Indian experience. International Zoo Yearbook, 17:98-101. 1978 Jungius, H. 1978. Criteria for the reintroduction of threatened species into parts of their former range. In: International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. Threatened Deer, pp. 342-352. Morges, Switzerland: IUCN. 1979 Anon. 1979. Reintroduction hazards. Oryx, 15:80. 1980 Campbell, S. 1980. Is reintroduction a realistic goal? In: M.E. Soule and B.A. Wilcox, eds. Conservation Biology: An Evolutionary-Ecological Perspective, pp. 263-269. Sunderland, Massachusetts: Sinaur. -

Breeding Biology and Behaviour of the Forest Raven Corvus Tasmanicus in Southern Tasmania

Breeding Biology and Behaviour of the Forest Raven Corvus tasmanicus in southern Tasmania Clare Lawrence BSc (Hons) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science, School of Zoology, University of Tasmania May 2009 This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree of diploma by the University or any other institution. To the best of my knowledge and belief, this thesis contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due acknowledgement is made in the text. Clare Lawrence Of. o6 Date Statement of Authority of Access This thesis may be available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968 Clare Lawrence 0/. Date TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 ABSTRACT 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 5 1. GENERAL INTRODUCTION 6 1.1 The breeding biology of birds 6 1.2 The Corvids 11 1.3 The Australian Corvids 11 1.4 Corvus tasmanicus 13 1.4.1 Identification 13 1.4.2 Distribution 13 1.4.3 Life history 15 1.4.4 Interspecific comparisons 16 1.4.5 Previous studies 17 1.5 The Forest Raven in Tasmania 18 1.6 Aims 19 2. BREEDING BIOLOGY OF THE FOREST RAVEN IN SOUTHERN TASMANIA 21 2.1 Introduction 21 2.2 Methods 23 2.2.1 Study sites 23 2.2.2 Nest characteristics 28 2.2.3 Field observations 31 2.2.4 Parental care 33 2.3 Results 37 2.3.1 Nests 37 2.3.2 Nest success and productivity 42 2.3.3 Breeding season • 46 2.3.4 Parental care 52 2.4 Discussion 66 2.4.1 The nest 68 1 2.4.2 Nest success and productivity 78 2.4.3 Breeding season 82 2.4.4 Parental care 88 2.4.5 Limitations of this study 96 2.5 Conclusion 98 3. -

Foraging Ecology of the Hawaiian Crow, an Endangered Generalist’

TheCondor88:211-219 0 The Cooper Ornithological Society 1986 FORAGING ECOLOGY OF THE HAWAIIAN CROW, AN ENDANGERED GENERALIST’ HOWARD F. SAKAI~ USDA Forest Service,Pacific SouthwestForest and Range Experiment Station, Institute of Pacific Islands Forestry Honolulu, HA 96813 C. JOHN RALPH~ USDA Forest Service,Pacific SouthwestForest and Range Experiment Station, Institute of Pacific Islands Forestry, Honolulu, HA 96813 C. D. JENKINS Department of Wildhfe Ecology,Russell Laboratory, Universityof Wisconsin,Madison, WI 53706 Abstract. The hypothesis that food was limiting the population of the endangeredHawaiian Crow (Corvus hawaiiensis)was investigated by observing its foraging habits. This crow was an omnivore, feeding on a wide variety of items including fruits, invertebrates, flower nectar, mam- mals, plant parts, and passerineeggs and nestlings.It was also an opportunistic feeder, shifting to readily available resources.The crow was adept at finding passerinenests, using this high protein diet of nestlingsand eggsduring the passerinebreeding season.Oha kepau (Clermontia spp.) and olapa (Cheirodendrontrigynum) comprised the bulk of the fruits taken. Arachnida and Isopoda were the predominant invertebrates found in droppings. Crows used the upper half of the canopy of mature trees,especially ohia (Metrosideroscollina) and koa (Acaciakoa), for their daily activities. Although the sample size was small, in the study area food seemed to be reasonably plentiful, and the crows were adaptable. Therefore, other factors probably are restricting the population. Efforts to maintain present habitat of the Hawaiian Crow need to be increased,with emphasis on ensuringa temporally continuous sourceof food. Key words: Hawaiian Crow; Corvus hawaiiensis;Hawaii; feeding strategy. INTRODUCTION pensis)in South Africa (Skead 1952); various The endangered Hawaiian Crow (Corvus ha- Australian crows and ravens, C.