Foraging Ecology of the Hawaiian Crow, an Endangered Generalist’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hulu the Palila, Activity 4

ACTIVITY 3: Find my favorite things! Hi! It’s Hulu again. I’m a Palila, a finch-billed Hawaiian honeycreeper. We only live in Hawai‘i. Would you like to know a little more about me? My favorite food: seeds from the māmane tree. This plant has beautiful yellow flowers, is in the pea and bean family, and is only found in Hawaii (endemic to Hawaii). Other foods I like: naio berries, caterpillars. Where I live: on the upper slopes of Mauna Kea on Hawai‘i Island. I like to live where the māmane tree can be found. Unfortunately, there aren’t so many of these trees left because the dryland forest got destroyed! Some places where my family used to live: not only Mauna Kea, but also on Mauna Loa and Hualālai; my family used to live in an area 10X bigger than now! Nesting materials: I used grasses, stems, roots, lichen and branch bark from the māmane tree to build my nest. And usually I raise two eggs at a time. My favorite place to visit: the Keauhou Bird Conservation Center Discovery Forest. Check out the next page to see if you can find words about me. Till next time, A hui hou! Hulu P.S. Watch your inbox. I’ll see you again soon! © 2020. Hawai‘i Forest Institute. All rights reserved. Things you learned about me this time Things you learned about me last time - Find the words! and this time – Find the words! g w r f m v c n e u h i c d e s h e e p m u a g v l z h e e j c h a l i f a a w s a x y f u v n t u j o q l c q a i n n j h n a m o d e x g t l t b j j h d u n q z s x i b p l d a k e p e o o w b g e h a c l l t d i i g o n r q i l u o a -

BIRDCONSERVATION the Magazine of American Bird Conservancy Fall 2016 BIRD’S EYE VIEW a Life Shaped by Migration

BIRDCONSERVATION The Magazine of American Bird Conservancy Fall 2016 BIRD’S EYE VIEW A Life Shaped By Migration The years have rolled by, leaving me with many memories touched by migrating birds. Migrations tell the chronicle of my life, made more poignant by their steady lessening through the years. still remember my first glimmer haunting calls of the cranes and Will the historic development of of understanding of the bird swans together, just out of sight. improved relations between the Imigration phenomenon. I was U.S. and Cuba nonetheless result in nine or ten years old and had The years have rolled by, leaving me the loss of habitats so important to spotted a male Yellow Warbler in with many memories touched by species such as the Black-throated spring plumage. Although I had migrating birds. Tracking a Golden Blue Warbler (page 18)? And will passing familiarity with the year- Eagle with a radio on its back Congress strengthen or weaken the round and wintertime birds at through downtown Milwaukee. Migratory Bird Treaty Act (page home, this springtime beauty was Walking down the Cape May beach 27), America’s most important law new to me. I went to my father for each afternoon to watch the Least protecting migratory birds? an explanation of how I had missed Tern colony. The thrill of seeing this bird before. Dad explained bird “our” migrants leave Colombia to We must address each of these migration, a talk that lit a small pour back north. And, on a recent concerns and a thousand more, fire in me that has never been summer evening, standing outside but we cannot be daunted by their extinguished. -

Alalā Or Hawaiian Crow (Corvus Hawaiiensis) 5-Year

`Alalā or Hawaiian Crow (Corvus hawaiiensis) 5-Year Review Summary and Evaluation U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Pacific Islands Fish and Wildlife Office Honolulu, Hawai`i 5-YEAR REVIEW Species reviewed: `Alalā or Hawaiian Crow (Corvus hawaiiensis) TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 GENERAL INFORMATION .......................................................................................... 1 1.1 Reviewers ....................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Methodology used to complete the review: ................................................................. 1 1.3 Background ................................................................................................................... 1 2.0 REVIEW ANALYSIS ....................................................................................................... 2 2.1 Application of the 1996 Distinct Population Segment (DPS) policy ......................... 2 2.2 Recovery Criteria .......................................................................................................... 3 2.3 Updated Information and Current Species Status .................................................... 4 2.4 Synthesis......................................................................................................................... 9 3.0 RESULTS .......................................................................................................................... 9 3.1 Recommended Classification ...................................................................................... -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 74/Thursday, April 16, 2020/Rules

21282 Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 74 / Thursday, April 16, 2020 / Rules and Regulations DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR United States and the Government of United States or U.S. territories as a Canada Amending the 1916 Convention result of recent taxonomic changes; Fish and Wildlife Service between the United Kingdom and the (8) Change the common (English) United States of America for the names of 43 species to conform to 50 CFR Part 10 Protection of Migratory Birds, Sen. accepted use; and (9) Change the scientific names of 135 [Docket No. FWS–HQ–MB–2018–0047; Treaty Doc. 104–28 (December 14, FXMB 12320900000//201//FF09M29000] 1995); species to conform to accepted use. (2) Mexico: Convention between the The List of Migratory Birds (50 CFR RIN 1018–BC67 United States and Mexico for the 10.13) was last revised on November 1, Protection of Migratory Birds and Game 2013 (78 FR 65844). The amendments in General Provisions; Revised List of this rule were necessitated by nine Migratory Birds Mammals, February 7, 1936, 50 Stat. 1311 (T.S. No. 912), as amended by published supplements to the 7th (1998) AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, Protocol with Mexico amending edition of the American Ornithologists’ Interior. Convention for Protection of Migratory Union (AOU, now recognized as the American Ornithological Society (AOS)) ACTION: Final rule. Birds and Game Mammals, Sen. Treaty Doc. 105–26 (May 5, 1997); Check-list of North American Birds (AOU 2011, AOU 2012, AOU 2013, SUMMARY: We, the U.S. Fish and (3) Japan: Convention between the AOU 2014, AOU 2015, AOU 2016, AOS Wildlife Service (Service), revise the Government of the United States of 2017, AOS 2018, and AOS 2019) and List of Migratory Birds protected by the America and the Government of Japan the 2017 publication of the Clements Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA) by for the Protection of Migratory Birds and Checklist of Birds of the World both adding and removing species. -

Appendix, French Names, Supplement

685 APPENDIX Part 1. Speciesreported from the A.O.U. Check-list area with insufficient evidencefor placementon the main list. Specieson this list havebeen reported (published) as occurring in the geographicarea coveredby this Check-list.However, their occurrenceis considered hypotheticalfor one of more of the following reasons: 1. Physicalevidence for their presence(e.g., specimen,photograph, video-tape, audio- recording)is lacking,of disputedorigin, or unknown.See the Prefacefor furtherdiscussion. 2. The naturaloccurrence (unrestrained by humans)of the speciesis disputed. 3. An introducedpopulation has failed to becomeestablished. 4. Inclusionin previouseditions of the Check-listwas basedexclusively on recordsfrom Greenland, which is now outside the A.O.U. Check-list area. Phoebastria irrorata (Salvin). Waved Albatross. Diornedeairrorata Salvin, 1883, Proc. Zool. Soc. London, p. 430. (Callao Bay, Peru.) This speciesbreeds on Hood Island in the Galapagosand on Isla de la Plata off Ecuador, and rangesat seaalong the coastsof Ecuadorand Peru. A specimenwas takenjust outside the North American area at Octavia Rocks, Colombia, near the Panama-Colombiaboundary (8 March 1941, R. C. Murphy). There are sight reportsfrom Panama,west of Pitias Bay, Dari6n, 26 February1941 (Ridgely 1976), and southwestof the Pearl Islands,27 September 1964. Also known as GalapagosAlbatross. ThalassarchechrysosWma (Forster). Gray-headed Albatross. Diornedeachrysostorna J. R. Forster,1785, M6m. Math. Phys. Acad. Sci. Paris 10: 571, pl. 14. (voisinagedu cerclepolaire antarctique & dansl'Ocean Pacifique= Isla de los Estados[= StatenIsland], off Tierra del Fuego.) This speciesbreeds on islandsoff CapeHorn, in the SouthAtlantic, in the southernIndian Ocean,and off New Zealand.Reports from Oregon(mouth of the ColumbiaRiver), California (coastnear Golden Gate), and Panama(Bay of Chiriqu0 are unsatisfactory(see A.O.U. -

Palila Loxioides Bailleui

Forest Birds Palila Loxioides bailleui SPECIES STATUS: Federally Listed as Endangered State Listed as Endangered State Recognized as Endemic NatureServe Heritage Rank G1—Critically Imperiled IUCN Red List Ranking—Critically Endangered Photo: DOFAW Revised Recovery Plan for Hawaiian Forest Birds —USFWS 2006 Critical Habitat Designated 1977 SPECIES INFORMATION: The palila is a finch-billed Hawaiian honeycreeper (Family: Fringillidae) whose life history and survival is linked to māmane (Sophora chrysophylla), an endemic dry-forest tree in the legume family. Males and females are similar, with a yellow head and breast, greenish wings and tail, a gray back, and white underparts. Males have a black mask, and females have less yellow on the back of their heads and a gray mask. Approximately 90 percent of the palila’s diet consists of immature māmane seeds; the remainder consists of māmane flowers, buds, leaves, and naio (Myoporum sandwicense) berries. Caterpillars and other insects comprise the diet of nestlings, but also are eaten by adults. Māmane seeds have been found to contain high levels of toxic alkaloids, and palila use particular trees for foraging, suggesting that levels of alkaloids may vary among trees. Individuals will move limited distances in response to the availability of māmane seeds. Palila form long-term pair bonds, and males perform low advertisement flights, sing, chase females, and engage in courtship feeding prior to breeding. Females build nests, usually in māmane trees, and males defend a small territory around the nest tree. Females mostly incubate eggs, brood nestlings and feed young with food delivered by male. First-year males sometimes help a pair by defending the nest and feeding the female and nestlings. -

Alpha Codes for 2154 Bird Species (And 108 Non-Species Taxa) in Accordance with the 60Th AOU Supplement (2019), Sorted Alphabetically by English Name

Four-letter (English Name) and Six-letter (Scientific Name) Alpha Codes for 2154 Bird Species (and 108 Non-Species Taxa) in accordance with the 60th AOU Supplement (2019), sorted alphabetically by English name Prepared by Peter Pyle and David F. DeSante The Institute for Bird Populations www.birdpop.org ENGLISH NAME 4-LETTER CODE SCIENTIFIC NAME 6-LETTER CODE Abert's Towhee ABTO Melozone aberti MELABE Acadian Flycatcher ACFL Empidonax virescens EMPVIR Acorn Woodpecker ACWO Melanerpes formicivorus MELFOR Adelaide's Warbler ADWA Setophaga adelaidae SETADE African Collared-Dove AFCD Streptopelia roseogrisea STRROS African Silverbill AFSI Euodice cantans EUOCAN Agami Heron AGHE Agamia agami AGAAGA Ainley's Storm-Petrel AISP Hydrobates cheimomnestes HYDCHE Akekee AKEK Loxops caeruleirostris LOXCAE Akiapolaau AKIA Hemignathus wilsoni HEMWIL Akikiki AKIK Oreomystis bairdi OREBAI Akohekohe AKOH Palmeria dolei PALDOL Alder Flycatcher ALFL Empidonax alnorum EMPALN + Aleutian Cackling Goose ACGO Branta hutchinsii leucopareia BRAHLE Aleutian Tern ALTE Onychoprion aleuticus ONYALE Allen's Hummingbird ALHU Selasphorus sasin SELSAS Alpine Swift ALSW Apus melba APUMEL Altamira Oriole ALOR Icterus gularis ICTGUL Altamira Yellowthroat ALYE Geothlypis flavovelata GEOFLA Amaui AMAU Myadestes woahensis MYAWOA Amazon Kingfisher AMKI Chloroceryle amazona CHLAMA American Avocet AMAV Recurvirostra americana RECAME American Bittern AMBI Botaurus lentiginosus BOTLEN American Black Duck ABDU Anas rubripes ANARUB + American Black Duck X Mallard Hybrid ABMH* Anas -

Observations on the Breeding of the Palila Psitt1rostra

462 C. VAN RIPER 111 IBIS122 OBSERVATIONS ON THE BREEDING OF THE PALILA PSITTIROSTRA BAILLEUI OF HAWAII CHARLESVAN RIPER111 Received 2 June 1979 The Palila Psittirostra bailleui, one of six species of its genus (Amadon 1950), was first collected in the Kona District of Hawaii by Bailleu in 1876 (Oustalet 1877). Historically the Palila was confined to the mamane Sophora chrysophylla and mamane-naio Myoporum sandwicense forests at high elevations on the mountains of Mauna Kca, Hualalai and Mauna Loa (Wilson & Evans 1890-1899, Perkins 1893, Rothschild 1893-1900). This range has been greatly reduced since the turn of the century. The bird is now found only on c. 5560 ha of Mauna Kea, occupying merely 10% of its former range. The present population is estimated to be 1500-1700 individuals at densities of approximately 37 birds per 100 ha (van Riper, Scott & Woodside 1978). Habitat degradation has been extensive in Hawaii, yet little work has been carried out concerning the effects of habitat alteration on the endemic organisms. The Palila is specialized in its feeding habits, being totally reliant upon the mamane ecosystem, which is rapidly diminishing (Warner 1960). This study was undertaken to define thc basic breeding parameters of the remaining population on Mauna Kea, and to identify reasons why the bird is today so rare. METHODS The study extended from 1970 through 1975, with 757 days spent in the field. During the last three years data were collected in every month, Study sites were at 1980, 2130 and 2290m in the Kaohe and Mauna Kea Game Management areas at Puu Laau on the southwestern slope of Mauna Kea, Hawaii (Fig. -

Seed Dispersal by a Captive Corvid: the Role of the 'Alala¯ (Corvus

Ecological Applications, 22(6), 2012, pp. 1718–1732 Ó 2012 by the Ecological Society of America Seed dispersal by a captive corvid: the role of the ‘Alala¯ (Corvus hawaiiensis) in shaping Hawai‘i’s plant communities 1,4 1 2 1,3 SUSAN CULLINEY, LIBA PEJCHAR, RICHARD SWITZER, AND VIVIANA RUIZ-GUTIERREZ 1Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Conservation Biology, Colorado State University, 1474 Campus Delivery, Fort Collins, Colorado 80523 USA 2Hawai‘i Endangered Bird Conservation Program, San Diego Zoo Institute for Conservation Research, Volcano, Hawaii 96785 USA 3Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, 159 Sapsucker Woods Road, Cornell University, Ithaca, NewYork 14850 USA Abstract. Species loss can lead to cascading effects on communities, including the disruption of ecological processes such as seed dispersal. The endangered ‘Alala¯ (Corvus hawaiiensis), the largest remaining species of native Hawaiian forest bird, was once common in mesic and dry forests on the Big Island of Hawai‘i, but today it exists solely in captivity. Prior to its extinction in the wild, the ‘Alala¯ may have helped to establish and maintain native Hawaiian forest communities by dispersing seeds of a wide variety of native plants. In the absence of ‘Alala¯, the structure and composition of Hawai‘i’s forests may be changing, and some large-fruited plants may be dispersal limited, persisting primarily as ecological anachronisms. We fed captive ‘Alala¯ a variety of native fruits, documented behaviors relating to seed dispersal, and measured the germination success of seeds that passed through the gut of ‘Alala¯ relative to the germination success of seeds in control groups. ‘Alala¯ ate and carried 14 native fruits and provided germination benefits to several species by ingesting their seeds. -

Palila Restoration Research, 1996−2012 Summary and Management Implications

Technical Report HCSU-046A PALILA RESTOratION RESEarch, 1996−2012 SUMMARY AND MANAGEMENT IMPLIcatIONS Paul C. Banko1 and Chris Farmer2, Editors 1 U.S. Geological Survey, Pacific Island Ecosystems Research Center, Kīlauea Field Station, P.O. Box 44, Hawaii National Park, HI 96718 2 American Bird Conservancy, Kīlauea Field Station, P.O. Box 44, Hawaii National Park, HI 96718 Hawai‘i Cooperative Studies Unit University of Hawai‘i at Hilo 200 W. Kawili St. Hilo, HI 96720 (808) 933-0706 October 2014 Citation: Banko, P. C., and C. Farmer, editors. 2014. Palila restoration research, 1996–2012: summary and management implications. Hawai‘i Cooperative Studies Unit Technical Report HCSU-046A. University of Hawai‘i at Hilo. 70 pages. This product was prepared under Cooperative Agreements CA03WRAG0036-3036WS0012, CA03WRAG0036-3036WS0032, and CAG09AC00041 for the Pacific Island Ecosystems Research Center of the U.S. Geological Survey. This article has been peer reviewed and approved for publication consistent with USGS Fundamental Science Practices (http://pubs.usgs.gov/circ/1367/). Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. PALILA RESTORATION RESEARCH, 1996–2012: SUMMARY AND MANAGEMENT IMPLICATIONS A palila (Loxioides bailleui) selects a seedpod from a māmane (Sophora chrysophylla) tree high on the western slope of Mauna Kea, Hawai‘i. The palila’s ecology and existence are inextricably linked to green māmane seeds, their critically important food. Chronic shortfalls in the supply of māmane seedpods could lead to the extinction of the palila. Photo by Jack Jeffrey (http://www.jackjeffreyphoto.com/). -

Times to Extinction for Small Populations of Large Birds (Crow/Owl/Hawk/Population Lifetime/Population Size) STUART L

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 90, pp. 10871-10875, November 1993 Population Biology Times to extinction for small populations of large birds (crow/owl/hawk/population lifetime/population size) STUART L. PIMM*, JARED DIAMONDt, TIMOTHY M. REEDt, GARETH J. RUSSELL*, AND JARED VERNER§ *Department of Zoology, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN 37996; tDepartment of Physiology, University of California Medical School, Los Angeles, CA 90024-1751; tJoint Nature Conservation Committee, Monkstone House, Peterborough, PE1 1UA, United Kingdom; and §U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Research Station, Fresno, CA 93710 Contributed by Jared Diamond, August 9, 1993 ABSTRACT A major practical problem in conservation such counts. European islands provide the most extensive biology is to predict the survival times-"lifetimes"-for small existing data set, and hence the best surrogates for 'Alala and populations under alternative proposed management regimes. Spotted Owl populations for the foreseeable future. The data Examples in the United States include the 'Alala (Hawaiian consist of counts of nesting birds tabulated in the annual Crow; Corvus hawaiiensis) and Northern Spotted Owl (Strix reports of bird observatories on small islands around the occidentalis caurina). To guide such decisions, we analyze coasts of Britain and Ireland, and on the German North Sea counts of ail crow, owl, and hawk species in the most complete island of Helgoland. Subsets of these data have been ana- available data set: counts of bird breeding pairs on 14 Euro- lyzed previously (2-9). pean islands censused for 29-66 consecutive years. The data set Our paper expands the previously analyzed data set to yielded 129 records for analysis. -

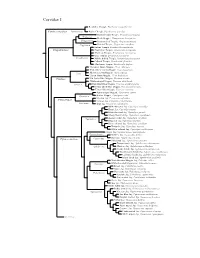

Corvidae Species Tree

Corvidae I Red-billed Chough, Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax Pyrrhocoracinae =Pyrrhocorax Alpine Chough, Pyrrhocorax graculus Ratchet-tailed Treepie, Temnurus temnurus Temnurus Black Magpie, Platysmurus leucopterus Platysmurus Racket-tailed Treepie, Crypsirina temia Crypsirina Hooded Treepie, Crypsirina cucullata Rufous Treepie, Dendrocitta vagabunda Crypsirininae ?Sumatran Treepie, Dendrocitta occipitalis ?Bornean Treepie, Dendrocitta cinerascens Gray Treepie, Dendrocitta formosae Dendrocitta ?White-bellied Treepie, Dendrocitta leucogastra Collared Treepie, Dendrocitta frontalis ?Andaman Treepie, Dendrocitta bayleii ?Common Green-Magpie, Cissa chinensis ?Indochinese Green-Magpie, Cissa hypoleuca Cissa ?Bornean Green-Magpie, Cissa jefferyi ?Javan Green-Magpie, Cissa thalassina Cissinae ?Sri Lanka Blue-Magpie, Urocissa ornata ?White-winged Magpie, Urocissa whiteheadi Urocissa Red-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa erythroryncha Yellow-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa flavirostris Taiwan Blue-Magpie, Urocissa caerulea Azure-winged Magpie, Cyanopica cyanus Cyanopica Iberian Magpie, Cyanopica cooki Siberian Jay, Perisoreus infaustus Perisoreinae Sichuan Jay, Perisoreus internigrans Perisoreus Gray Jay, Perisoreus canadensis White-throated Jay, Cyanolyca mirabilis Dwarf Jay, Cyanolyca nanus Black-throated Jay, Cyanolyca pumilo Silvery-throated Jay, Cyanolyca argentigula Cyanolyca Azure-hooded Jay, Cyanolyca cucullata Beautiful Jay, Cyanolyca pulchra Black-collared Jay, Cyanolyca armillata Turquoise Jay, Cyanolyca turcosa White-collared Jay, Cyanolyca viridicyanus