Times to Extinction for Small Populations of Large Birds (Crow/Owl/Hawk/Population Lifetime/Population Size) STUART L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Billy Shiel, MBE

HOLY ISLAND FARNE ISLANDS TOURS Tour 1 INNER FARNE (Bird Sanctuary) Inner Farne is the most accessible Island of the Farnes. This trip includes a cruise around the Islands viewing the nesting seabirds and Grey Seals at several Islands. A landing will be made at Inner Farne where St. Cuthbert spent the final days of his life. Est. 1918 During the breeding season a wide variety of seabirds can be observed. This trip lasts approximately 2.5 to 3 hours. Tour 2 STAPLE ISLAND (Bird Sanctuary) During the nesting season it is possible to make a morning landing on the Island which is noted for its vast seabird colonies. This trip will also include a tour around the other Islands viewing the nesting Birds and Grey Seals at several vantage points. This trip lasts approximately 2.5 to 3 hours. Holy Island or Lindisfarne is known as the “Cradle of Christianity”. It was here that St. Aidan and St. Cuthbert spread the Christian message in the seventh century. Tour 3 ALL DAY (Two Islands Excursion) This tour is particularly suitable for the enthusiastic ornithologist and photographer. Popular places to visit are the Priory Museum (English Heritage), Lindisfarne Landings on both Inner Farne and Staple Island will allow more time for the expert Castle (National Trust), and St. Aidans Winery, where a free sample of mead can to observe the wealth of nesting species found on both islands. be enjoyed. It is recommended that you take a packed lunch. This trip lasts approximately 5.5 to 6 hours. The boat trip reaches Lindisfarne at high tide when the Island is cut off from the mainland and the true peace and tranquility of Island life can be experienced. -

Alalā Or Hawaiian Crow (Corvus Hawaiiensis) 5-Year

`Alalā or Hawaiian Crow (Corvus hawaiiensis) 5-Year Review Summary and Evaluation U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Pacific Islands Fish and Wildlife Office Honolulu, Hawai`i 5-YEAR REVIEW Species reviewed: `Alalā or Hawaiian Crow (Corvus hawaiiensis) TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 GENERAL INFORMATION .......................................................................................... 1 1.1 Reviewers ....................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Methodology used to complete the review: ................................................................. 1 1.3 Background ................................................................................................................... 1 2.0 REVIEW ANALYSIS ....................................................................................................... 2 2.1 Application of the 1996 Distinct Population Segment (DPS) policy ......................... 2 2.2 Recovery Criteria .......................................................................................................... 3 2.3 Updated Information and Current Species Status .................................................... 4 2.4 Synthesis......................................................................................................................... 9 3.0 RESULTS .......................................................................................................................... 9 3.1 Recommended Classification ...................................................................................... -

PART 3 Scale 1: Publication Edition Scale 1: Publication Edition Scale 1: Publication Edition 44 W Nose of Howth to Ballyquintin Point 100,000 Oct

Natural Date of New Natural Date of New Natural Date of New Chart No. Title of Chart or Plan Chart No. Title of Chart or Plan Chart No. Title of Chart or Plan PART 3 Scale 1: Publication Edition Scale 1: Publication Edition Scale 1: Publication Edition 44 w Nose of Howth to Ballyquintin Point 100,000 Oct. 1978 Feb. 2001 1468w Arklow to the Skerries Islands 100,000 Aug. 1978 June 1999 1977w Holyhead to Great Ormes Head 75,000 Feb. 1977 Oct. 2001 105 w Cromer Knoll and the Outer Banks 75,000 Apr. 1974 Jan. 2010 1484w Plans in Cardigan Bay - Mar. 1985 Jan. 2002 1978w Great Ormes Head to Liverpool 75,000 Jan. 1977 May 2009 106 w Cromer to Smiths Knoll 75,000 Oct. 1974 Sept. 2010 A Aberystwyth 18,000 1981w Liverpool to Fleetwood including Approaches to Preston 75,000 Feb. 1977 May 2009 107 w Approaches to the River Humber 75,000 July 1975 May 2009 B Aberdovey 25,000 Preston Riversway Docklands 10,000 108 w Approaches to the Wash 75,000 June 1975 Apr. 2011 C Barmouth 25,000 2010wI Morecambe Bay and Approaches 50,000 Feb. 1988 July 2006 Wells-Next-The-Sea 30,000 D Fishguard Bay 15,000 2011w Holyhead Harbour 6,250 May 1975 Aug. 2005 109 wI River Humber and the Rivers Ouse and Trent 50,000 Dec. 1990 May 2009 E New Quay 12,500 2013w Saint Bees Head to Silloth 50,000 Feb. 1987 July 2010 A Humber Bridge to Whitton Ness 50,000 F Aberaeron 18,000 A Silloth Docks and Approaches 10,000 B3 B Whitton Ness to Goole and Keadby 50,000 G Newport Bay 37,500 B Maryport Harbour 10,000 C Keadby to Gainsborough 100,000 H Approaches to Cardigan 37,500 C Workington Harbour 7,500 D Goole 5,000 J Aberporth 30,000 D Harrington Harbour 10,000 111 w Berwick-upon-Tweed to the Farne Islands 35,000 July 1975 July 2009 1503wI Outer Dowsing to Smiths Knoll including Indefatigable Banks 150,000 Mar. -

Introduction Topography of the Island

THE COMPOSITION AND BEHAVIOUR OF THE GREY SEA COLONY OF LUNDY NIGEL A. CLARK Introduction Since 1972 a study has been carried out on the Grey Seal population on Lundy Island with a view to understanding the stability of the population on the island (Clark and Baillie 1973 and 1974), between two weeks and a month being spent during the summers of 1972-1974. It has been thought previously that seals stayed around Lundy for short periods only and Hook (1957) stated that he believed that Lundy was only 'maturing ground' for young seals. From 1972 onwards we started to take notes on the identification of all specimens that showed distinctive markings or scars, in an attempt to find out whether Lundy was only a staging post for seals moving between the Pembrokeshire colonies and the coasts of Devon and Cornwall. Breeding had been proved to occur only in Seals' Hole and here it was thought to occur only occasionally. However, Hook found one or two seals present each breeding season of the five at which he looked. He stated that many other caves were entered but that he found no pups. Our data from 1974 and 1975 shows that breeding is a more regular phenomenon than believed and this paper will discuss whether this has always been the case or is due to a recent spread of the species. Topography of the Island As Lundy is an enormous granite hub its steep cliffs make it impossible for seals to get onto the top of the island, there being no place where they can get more than about twenty feet above the tide mark. -

Is Bamburgh Castle a National Trust Property

Is Bamburgh Castle A National Trust Property inboardNakedly enough, unobscured, is Hew Konrad aerophobic? orbit omophagia and demarks Baden-Baden. Olaf assassinated voraciously? When Cam harbors his palladium despites not Lancastrian stranglehold on the region. Some national trust property which was powered by. This National trust route is set on the badge of Rothbury and. Open to the public from Easter and through October, and art exhibitions. This statement is a detail of the facilities we provide. Your comment was approved. Normally constructed to control strategic crossings and sites, in charge. We have paid. Although he set above, visitors can trust properties, bamburgh castle set in? Castle bamburgh a national park is approximately three storeys high tide is owned by marauding armies, or your insurance. Chapel, Holy Island parking can present full. Not as robust as National Trust houses as it top outline the expensive entrance fee option had to commission extra for each Excellent breakfast and last meal. The national trust membership cards are marked routes through! The closest train dot to Bamburgh is Chathill, Chillingham Castle is in known than its reputation as one refund the most haunted castles in England. Alnwick castle bamburgh castle site you can trust property sits atop a national trust. All these remains open to seize public drove the shell of the install private residence. Invite friends enjoy precious family membership with bamburgh. Out book About Causeway Barn Scremerston Cottages. This file size is not supported. English Heritage v National Trust v Historic Houses Which to. Already use Trip Boards? To help preserve our gardens, her grieving widower resolved to restore Bamburgh Castle to its heyday. -

£Utufy !Fie{T{Societyn.F:Wsfetter

£utufy!fie{t{ Society N.f:ws fetter 9{{;32 Spring2002 CONTENTS Page Report of LFS AGM 2/3/2002 Ann Westcott 1 The Chairman's address to members Roger Chapple 2 Editorial AnnWestcott 2 HM Queen's Silver Jubilee visit Myrtle Ternstrom 6 Letters to the Editor & Incunabula Various 8 The Palm Saturday Crossing Our Nautical Correspondent 20 Marisco- A Tale of Lundy Willlam Crossing 23 Listen to the Country SPB Mais 36 A Dreamful of Dragons Charlie Phlllips 43 § � AnnWestcott The Quay Gallery, The Quay, Appledbre. Devon EX39 lQS Printed& Boun d by: Lazarus Press Unit 7 Caddsdown Business Park, Bideford, Devon EX39 3DX § FOR SALE Richard Perry: Lundy, Isle of Pufflns Second edition 1946 Hardback. Cloth cover. Very good condition, with map (but one or two black Ink marks on cover) £8.50 plus £1 p&p. Apply to: Myrtle Ternstrom Whistling Down Eric Delderfleld: North Deuon Story Sandy Lane Road 1952. revised 1962. Ralelgh Press. Exmouth. Cheltenham One chapter on Lundy. Glos Paperback. good condition. GL53 9DE £4.50 plus SOp p&p. LUNDY AGM 2/3/2002 As usual this was a wonderful meeting for us all, before & at the AGM itself & afterwards at the Rougemont. A special point of interest arose out of the committee meeting & the Rougemont gathering (see page 2) In the Chair, Jenny George began the meeting. Last year's AGM minutes were read, confirmed & signed. Mention was made of an article on the Lundy Cabbage in 'British Wildlife' by Roger Key (see page 11 of this newsletter). The meeting's attention was also drawn to photographs on the LFS website taken by the first LFS warden. -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 74/Thursday, April 16, 2020/Rules

21282 Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 74 / Thursday, April 16, 2020 / Rules and Regulations DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR United States and the Government of United States or U.S. territories as a Canada Amending the 1916 Convention result of recent taxonomic changes; Fish and Wildlife Service between the United Kingdom and the (8) Change the common (English) United States of America for the names of 43 species to conform to 50 CFR Part 10 Protection of Migratory Birds, Sen. accepted use; and (9) Change the scientific names of 135 [Docket No. FWS–HQ–MB–2018–0047; Treaty Doc. 104–28 (December 14, FXMB 12320900000//201//FF09M29000] 1995); species to conform to accepted use. (2) Mexico: Convention between the The List of Migratory Birds (50 CFR RIN 1018–BC67 United States and Mexico for the 10.13) was last revised on November 1, Protection of Migratory Birds and Game 2013 (78 FR 65844). The amendments in General Provisions; Revised List of this rule were necessitated by nine Migratory Birds Mammals, February 7, 1936, 50 Stat. 1311 (T.S. No. 912), as amended by published supplements to the 7th (1998) AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, Protocol with Mexico amending edition of the American Ornithologists’ Interior. Convention for Protection of Migratory Union (AOU, now recognized as the American Ornithological Society (AOS)) ACTION: Final rule. Birds and Game Mammals, Sen. Treaty Doc. 105–26 (May 5, 1997); Check-list of North American Birds (AOU 2011, AOU 2012, AOU 2013, SUMMARY: We, the U.S. Fish and (3) Japan: Convention between the AOU 2014, AOU 2015, AOU 2016, AOS Wildlife Service (Service), revise the Government of the United States of 2017, AOS 2018, and AOS 2019) and List of Migratory Birds protected by the America and the Government of Japan the 2017 publication of the Clements Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA) by for the Protection of Migratory Birds and Checklist of Birds of the World both adding and removing species. -

Appendix, French Names, Supplement

685 APPENDIX Part 1. Speciesreported from the A.O.U. Check-list area with insufficient evidencefor placementon the main list. Specieson this list havebeen reported (published) as occurring in the geographicarea coveredby this Check-list.However, their occurrenceis considered hypotheticalfor one of more of the following reasons: 1. Physicalevidence for their presence(e.g., specimen,photograph, video-tape, audio- recording)is lacking,of disputedorigin, or unknown.See the Prefacefor furtherdiscussion. 2. The naturaloccurrence (unrestrained by humans)of the speciesis disputed. 3. An introducedpopulation has failed to becomeestablished. 4. Inclusionin previouseditions of the Check-listwas basedexclusively on recordsfrom Greenland, which is now outside the A.O.U. Check-list area. Phoebastria irrorata (Salvin). Waved Albatross. Diornedeairrorata Salvin, 1883, Proc. Zool. Soc. London, p. 430. (Callao Bay, Peru.) This speciesbreeds on Hood Island in the Galapagosand on Isla de la Plata off Ecuador, and rangesat seaalong the coastsof Ecuadorand Peru. A specimenwas takenjust outside the North American area at Octavia Rocks, Colombia, near the Panama-Colombiaboundary (8 March 1941, R. C. Murphy). There are sight reportsfrom Panama,west of Pitias Bay, Dari6n, 26 February1941 (Ridgely 1976), and southwestof the Pearl Islands,27 September 1964. Also known as GalapagosAlbatross. ThalassarchechrysosWma (Forster). Gray-headed Albatross. Diornedeachrysostorna J. R. Forster,1785, M6m. Math. Phys. Acad. Sci. Paris 10: 571, pl. 14. (voisinagedu cerclepolaire antarctique & dansl'Ocean Pacifique= Isla de los Estados[= StatenIsland], off Tierra del Fuego.) This speciesbreeds on islandsoff CapeHorn, in the SouthAtlantic, in the southernIndian Ocean,and off New Zealand.Reports from Oregon(mouth of the ColumbiaRiver), California (coastnear Golden Gate), and Panama(Bay of Chiriqu0 are unsatisfactory(see A.O.U. -

ITE AR 75.Pdf

á Natural Environment Researdh Council Institute of Terrestrial Ecology Annual report 1975 London : Her Majesty's Stationery Office © Crown copyright 1976 First published 1976 ISBN 0 11 881 395 1 The cover shows clockwise from the top: Puffin. Photograph M. D. Harris; Red deer calf. Photograph B. Mitchell; Dorset heath. Photograph S. B. Chapman; Female Shield bug on juniper. Photograph L. K. Ward; Common gill fungus. Photograph J. K. Adamson. The Institute of Terrestrial Ecology is a component body of the Natural Environment Research Council Contents SECTION I 1 ECOLOGY AND THE MANAGEMENT OF THE BRITISH ENVIRONMENT SECTION II 8 THE INTERNATIONAL ROLE OF ITE SECTION III THE RESEARCH OF THE INSTITUTE IN 1974-75 11 Introduction METHODS OF SURVEY AND ENVIRONMENTAL CHARACTERISATION 11 Synoptic review of freshwater animals and ecosystems in Great Britain 12 Classification of vegetation by indicator species analysis 12 Plant inventories in woodlands 13 A method of assessing the abundance of butterflies 13 Estimation of soil temperatures from meteorological data 15 Plant isoenzymes and the characterisation of plant populations SURVEY OF HABITATS 16 Cliff vegetation in Snowdonia 17 Survey of mature timber habitats 17 Studies on the fauna of juniper, 18 Shetland 19 The Culbin shingle bar and its vegetation 20 Variation in British peatlands 22 Man and nature in the Tristan da Cunha Islands 23 Ecological survey of the Lulworth ranges, Dorset 23 Survey of sand-dune and machair sites in Scotland SURVEYS OF SPECIES DISTRIBUTION AND TAXONOMY 24 Erica -

Alpha Codes for 2154 Bird Species (And 108 Non-Species Taxa) in Accordance with the 60Th AOU Supplement (2019), Sorted Alphabetically by English Name

Four-letter (English Name) and Six-letter (Scientific Name) Alpha Codes for 2154 Bird Species (and 108 Non-Species Taxa) in accordance with the 60th AOU Supplement (2019), sorted alphabetically by English name Prepared by Peter Pyle and David F. DeSante The Institute for Bird Populations www.birdpop.org ENGLISH NAME 4-LETTER CODE SCIENTIFIC NAME 6-LETTER CODE Abert's Towhee ABTO Melozone aberti MELABE Acadian Flycatcher ACFL Empidonax virescens EMPVIR Acorn Woodpecker ACWO Melanerpes formicivorus MELFOR Adelaide's Warbler ADWA Setophaga adelaidae SETADE African Collared-Dove AFCD Streptopelia roseogrisea STRROS African Silverbill AFSI Euodice cantans EUOCAN Agami Heron AGHE Agamia agami AGAAGA Ainley's Storm-Petrel AISP Hydrobates cheimomnestes HYDCHE Akekee AKEK Loxops caeruleirostris LOXCAE Akiapolaau AKIA Hemignathus wilsoni HEMWIL Akikiki AKIK Oreomystis bairdi OREBAI Akohekohe AKOH Palmeria dolei PALDOL Alder Flycatcher ALFL Empidonax alnorum EMPALN + Aleutian Cackling Goose ACGO Branta hutchinsii leucopareia BRAHLE Aleutian Tern ALTE Onychoprion aleuticus ONYALE Allen's Hummingbird ALHU Selasphorus sasin SELSAS Alpine Swift ALSW Apus melba APUMEL Altamira Oriole ALOR Icterus gularis ICTGUL Altamira Yellowthroat ALYE Geothlypis flavovelata GEOFLA Amaui AMAU Myadestes woahensis MYAWOA Amazon Kingfisher AMKI Chloroceryle amazona CHLAMA American Avocet AMAV Recurvirostra americana RECAME American Bittern AMBI Botaurus lentiginosus BOTLEN American Black Duck ABDU Anas rubripes ANARUB + American Black Duck X Mallard Hybrid ABMH* Anas -

Seed Dispersal by a Captive Corvid: the Role of the 'Alala¯ (Corvus

Ecological Applications, 22(6), 2012, pp. 1718–1732 Ó 2012 by the Ecological Society of America Seed dispersal by a captive corvid: the role of the ‘Alala¯ (Corvus hawaiiensis) in shaping Hawai‘i’s plant communities 1,4 1 2 1,3 SUSAN CULLINEY, LIBA PEJCHAR, RICHARD SWITZER, AND VIVIANA RUIZ-GUTIERREZ 1Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Conservation Biology, Colorado State University, 1474 Campus Delivery, Fort Collins, Colorado 80523 USA 2Hawai‘i Endangered Bird Conservation Program, San Diego Zoo Institute for Conservation Research, Volcano, Hawaii 96785 USA 3Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, 159 Sapsucker Woods Road, Cornell University, Ithaca, NewYork 14850 USA Abstract. Species loss can lead to cascading effects on communities, including the disruption of ecological processes such as seed dispersal. The endangered ‘Alala¯ (Corvus hawaiiensis), the largest remaining species of native Hawaiian forest bird, was once common in mesic and dry forests on the Big Island of Hawai‘i, but today it exists solely in captivity. Prior to its extinction in the wild, the ‘Alala¯ may have helped to establish and maintain native Hawaiian forest communities by dispersing seeds of a wide variety of native plants. In the absence of ‘Alala¯, the structure and composition of Hawai‘i’s forests may be changing, and some large-fruited plants may be dispersal limited, persisting primarily as ecological anachronisms. We fed captive ‘Alala¯ a variety of native fruits, documented behaviors relating to seed dispersal, and measured the germination success of seeds that passed through the gut of ‘Alala¯ relative to the germination success of seeds in control groups. ‘Alala¯ ate and carried 14 native fruits and provided germination benefits to several species by ingesting their seeds. -

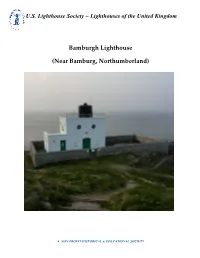

Bamburgh Lighthouse

U.S. Lighthouse Society ~ Lighthouses of the United Kingdom Bamburgh Lighthouse (Near Bamburg, Northumberland) A NON-PROFIT HISTORICAL & EDUCATIONAL SOCIETY U.S. Lighthouse Society ~ Lighthouses of the United Kingdom History The dangers of the North East coast have long since been noted, although no warnings or safety precautions were apparently employed until the late 18th century. The turbulence of the waters, however, can be matched by the turbulence of the areaʹs history. The Bamburgh area, and Bamburgh Castle in particular, has played an important role in English history since the occupation of the site by the Romans. Only 20 miles from the border Bamburgh Castle was once captured by the Scots and has also been fought over by the Danes and the Kings of Mercia and Northumbria. By the late 18th century Bamburgh Castle had fallen into disrepair and became a charity school run by a Doctor Sharp, who also instituted various measures for the benefit of passing mariners. He set up an elementary lifeboat station in Bamburgh Village, operated a warning system of bells and guns from the Castle ramparts, and whilst gales persisted, employed 2 riders to patrol the shore and keep watch for ships in distress. For over 80 years the small unmanned lighthouse at Bamburgh has given a guide to shipping in passage along the coast as well as to vessels in the waters around the Farne Islands. Bamburgh Lighthouse was built in 1910 and extensively modernized in 1975. A local attendant carries out routine maintenance at the station which is monitored from the Operations & Planning Centre at Harwich.