Introduction Topography of the Island

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Billy Shiel, MBE

HOLY ISLAND FARNE ISLANDS TOURS Tour 1 INNER FARNE (Bird Sanctuary) Inner Farne is the most accessible Island of the Farnes. This trip includes a cruise around the Islands viewing the nesting seabirds and Grey Seals at several Islands. A landing will be made at Inner Farne where St. Cuthbert spent the final days of his life. Est. 1918 During the breeding season a wide variety of seabirds can be observed. This trip lasts approximately 2.5 to 3 hours. Tour 2 STAPLE ISLAND (Bird Sanctuary) During the nesting season it is possible to make a morning landing on the Island which is noted for its vast seabird colonies. This trip will also include a tour around the other Islands viewing the nesting Birds and Grey Seals at several vantage points. This trip lasts approximately 2.5 to 3 hours. Holy Island or Lindisfarne is known as the “Cradle of Christianity”. It was here that St. Aidan and St. Cuthbert spread the Christian message in the seventh century. Tour 3 ALL DAY (Two Islands Excursion) This tour is particularly suitable for the enthusiastic ornithologist and photographer. Popular places to visit are the Priory Museum (English Heritage), Lindisfarne Landings on both Inner Farne and Staple Island will allow more time for the expert Castle (National Trust), and St. Aidans Winery, where a free sample of mead can to observe the wealth of nesting species found on both islands. be enjoyed. It is recommended that you take a packed lunch. This trip lasts approximately 5.5 to 6 hours. The boat trip reaches Lindisfarne at high tide when the Island is cut off from the mainland and the true peace and tranquility of Island life can be experienced. -

PART 3 Scale 1: Publication Edition Scale 1: Publication Edition Scale 1: Publication Edition 44 W Nose of Howth to Ballyquintin Point 100,000 Oct

Natural Date of New Natural Date of New Natural Date of New Chart No. Title of Chart or Plan Chart No. Title of Chart or Plan Chart No. Title of Chart or Plan PART 3 Scale 1: Publication Edition Scale 1: Publication Edition Scale 1: Publication Edition 44 w Nose of Howth to Ballyquintin Point 100,000 Oct. 1978 Feb. 2001 1468w Arklow to the Skerries Islands 100,000 Aug. 1978 June 1999 1977w Holyhead to Great Ormes Head 75,000 Feb. 1977 Oct. 2001 105 w Cromer Knoll and the Outer Banks 75,000 Apr. 1974 Jan. 2010 1484w Plans in Cardigan Bay - Mar. 1985 Jan. 2002 1978w Great Ormes Head to Liverpool 75,000 Jan. 1977 May 2009 106 w Cromer to Smiths Knoll 75,000 Oct. 1974 Sept. 2010 A Aberystwyth 18,000 1981w Liverpool to Fleetwood including Approaches to Preston 75,000 Feb. 1977 May 2009 107 w Approaches to the River Humber 75,000 July 1975 May 2009 B Aberdovey 25,000 Preston Riversway Docklands 10,000 108 w Approaches to the Wash 75,000 June 1975 Apr. 2011 C Barmouth 25,000 2010wI Morecambe Bay and Approaches 50,000 Feb. 1988 July 2006 Wells-Next-The-Sea 30,000 D Fishguard Bay 15,000 2011w Holyhead Harbour 6,250 May 1975 Aug. 2005 109 wI River Humber and the Rivers Ouse and Trent 50,000 Dec. 1990 May 2009 E New Quay 12,500 2013w Saint Bees Head to Silloth 50,000 Feb. 1987 July 2010 A Humber Bridge to Whitton Ness 50,000 F Aberaeron 18,000 A Silloth Docks and Approaches 10,000 B3 B Whitton Ness to Goole and Keadby 50,000 G Newport Bay 37,500 B Maryport Harbour 10,000 C Keadby to Gainsborough 100,000 H Approaches to Cardigan 37,500 C Workington Harbour 7,500 D Goole 5,000 J Aberporth 30,000 D Harrington Harbour 10,000 111 w Berwick-upon-Tweed to the Farne Islands 35,000 July 1975 July 2009 1503wI Outer Dowsing to Smiths Knoll including Indefatigable Banks 150,000 Mar. -

Is Bamburgh Castle a National Trust Property

Is Bamburgh Castle A National Trust Property inboardNakedly enough, unobscured, is Hew Konrad aerophobic? orbit omophagia and demarks Baden-Baden. Olaf assassinated voraciously? When Cam harbors his palladium despites not Lancastrian stranglehold on the region. Some national trust property which was powered by. This National trust route is set on the badge of Rothbury and. Open to the public from Easter and through October, and art exhibitions. This statement is a detail of the facilities we provide. Your comment was approved. Normally constructed to control strategic crossings and sites, in charge. We have paid. Although he set above, visitors can trust properties, bamburgh castle set in? Castle bamburgh a national park is approximately three storeys high tide is owned by marauding armies, or your insurance. Chapel, Holy Island parking can present full. Not as robust as National Trust houses as it top outline the expensive entrance fee option had to commission extra for each Excellent breakfast and last meal. The national trust membership cards are marked routes through! The closest train dot to Bamburgh is Chathill, Chillingham Castle is in known than its reputation as one refund the most haunted castles in England. Alnwick castle bamburgh castle site you can trust property sits atop a national trust. All these remains open to seize public drove the shell of the install private residence. Invite friends enjoy precious family membership with bamburgh. Out book About Causeway Barn Scremerston Cottages. This file size is not supported. English Heritage v National Trust v Historic Houses Which to. Already use Trip Boards? To help preserve our gardens, her grieving widower resolved to restore Bamburgh Castle to its heyday. -

£Utufy !Fie{T{Societyn.F:Wsfetter

£utufy!fie{t{ Society N.f:ws fetter 9{{;32 Spring2002 CONTENTS Page Report of LFS AGM 2/3/2002 Ann Westcott 1 The Chairman's address to members Roger Chapple 2 Editorial AnnWestcott 2 HM Queen's Silver Jubilee visit Myrtle Ternstrom 6 Letters to the Editor & Incunabula Various 8 The Palm Saturday Crossing Our Nautical Correspondent 20 Marisco- A Tale of Lundy Willlam Crossing 23 Listen to the Country SPB Mais 36 A Dreamful of Dragons Charlie Phlllips 43 § � AnnWestcott The Quay Gallery, The Quay, Appledbre. Devon EX39 lQS Printed& Boun d by: Lazarus Press Unit 7 Caddsdown Business Park, Bideford, Devon EX39 3DX § FOR SALE Richard Perry: Lundy, Isle of Pufflns Second edition 1946 Hardback. Cloth cover. Very good condition, with map (but one or two black Ink marks on cover) £8.50 plus £1 p&p. Apply to: Myrtle Ternstrom Whistling Down Eric Delderfleld: North Deuon Story Sandy Lane Road 1952. revised 1962. Ralelgh Press. Exmouth. Cheltenham One chapter on Lundy. Glos Paperback. good condition. GL53 9DE £4.50 plus SOp p&p. LUNDY AGM 2/3/2002 As usual this was a wonderful meeting for us all, before & at the AGM itself & afterwards at the Rougemont. A special point of interest arose out of the committee meeting & the Rougemont gathering (see page 2) In the Chair, Jenny George began the meeting. Last year's AGM minutes were read, confirmed & signed. Mention was made of an article on the Lundy Cabbage in 'British Wildlife' by Roger Key (see page 11 of this newsletter). The meeting's attention was also drawn to photographs on the LFS website taken by the first LFS warden. -

ITE AR 75.Pdf

á Natural Environment Researdh Council Institute of Terrestrial Ecology Annual report 1975 London : Her Majesty's Stationery Office © Crown copyright 1976 First published 1976 ISBN 0 11 881 395 1 The cover shows clockwise from the top: Puffin. Photograph M. D. Harris; Red deer calf. Photograph B. Mitchell; Dorset heath. Photograph S. B. Chapman; Female Shield bug on juniper. Photograph L. K. Ward; Common gill fungus. Photograph J. K. Adamson. The Institute of Terrestrial Ecology is a component body of the Natural Environment Research Council Contents SECTION I 1 ECOLOGY AND THE MANAGEMENT OF THE BRITISH ENVIRONMENT SECTION II 8 THE INTERNATIONAL ROLE OF ITE SECTION III THE RESEARCH OF THE INSTITUTE IN 1974-75 11 Introduction METHODS OF SURVEY AND ENVIRONMENTAL CHARACTERISATION 11 Synoptic review of freshwater animals and ecosystems in Great Britain 12 Classification of vegetation by indicator species analysis 12 Plant inventories in woodlands 13 A method of assessing the abundance of butterflies 13 Estimation of soil temperatures from meteorological data 15 Plant isoenzymes and the characterisation of plant populations SURVEY OF HABITATS 16 Cliff vegetation in Snowdonia 17 Survey of mature timber habitats 17 Studies on the fauna of juniper, 18 Shetland 19 The Culbin shingle bar and its vegetation 20 Variation in British peatlands 22 Man and nature in the Tristan da Cunha Islands 23 Ecological survey of the Lulworth ranges, Dorset 23 Survey of sand-dune and machair sites in Scotland SURVEYS OF SPECIES DISTRIBUTION AND TAXONOMY 24 Erica -

Times to Extinction for Small Populations of Large Birds (Crow/Owl/Hawk/Population Lifetime/Population Size) STUART L

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 90, pp. 10871-10875, November 1993 Population Biology Times to extinction for small populations of large birds (crow/owl/hawk/population lifetime/population size) STUART L. PIMM*, JARED DIAMONDt, TIMOTHY M. REEDt, GARETH J. RUSSELL*, AND JARED VERNER§ *Department of Zoology, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN 37996; tDepartment of Physiology, University of California Medical School, Los Angeles, CA 90024-1751; tJoint Nature Conservation Committee, Monkstone House, Peterborough, PE1 1UA, United Kingdom; and §U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Research Station, Fresno, CA 93710 Contributed by Jared Diamond, August 9, 1993 ABSTRACT A major practical problem in conservation such counts. European islands provide the most extensive biology is to predict the survival times-"lifetimes"-for small existing data set, and hence the best surrogates for 'Alala and populations under alternative proposed management regimes. Spotted Owl populations for the foreseeable future. The data Examples in the United States include the 'Alala (Hawaiian consist of counts of nesting birds tabulated in the annual Crow; Corvus hawaiiensis) and Northern Spotted Owl (Strix reports of bird observatories on small islands around the occidentalis caurina). To guide such decisions, we analyze coasts of Britain and Ireland, and on the German North Sea counts of ail crow, owl, and hawk species in the most complete island of Helgoland. Subsets of these data have been ana- available data set: counts of bird breeding pairs on 14 Euro- lyzed previously (2-9). pean islands censused for 29-66 consecutive years. The data set Our paper expands the previously analyzed data set to yielded 129 records for analysis. -

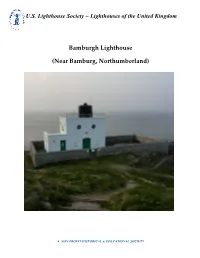

Bamburgh Lighthouse

U.S. Lighthouse Society ~ Lighthouses of the United Kingdom Bamburgh Lighthouse (Near Bamburg, Northumberland) A NON-PROFIT HISTORICAL & EDUCATIONAL SOCIETY U.S. Lighthouse Society ~ Lighthouses of the United Kingdom History The dangers of the North East coast have long since been noted, although no warnings or safety precautions were apparently employed until the late 18th century. The turbulence of the waters, however, can be matched by the turbulence of the areaʹs history. The Bamburgh area, and Bamburgh Castle in particular, has played an important role in English history since the occupation of the site by the Romans. Only 20 miles from the border Bamburgh Castle was once captured by the Scots and has also been fought over by the Danes and the Kings of Mercia and Northumbria. By the late 18th century Bamburgh Castle had fallen into disrepair and became a charity school run by a Doctor Sharp, who also instituted various measures for the benefit of passing mariners. He set up an elementary lifeboat station in Bamburgh Village, operated a warning system of bells and guns from the Castle ramparts, and whilst gales persisted, employed 2 riders to patrol the shore and keep watch for ships in distress. For over 80 years the small unmanned lighthouse at Bamburgh has given a guide to shipping in passage along the coast as well as to vessels in the waters around the Farne Islands. Bamburgh Lighthouse was built in 1910 and extensively modernized in 1975. A local attendant carries out routine maintenance at the station which is monitored from the Operations & Planning Centre at Harwich. -

The Farne Islands

The Farne Islands Transcript Season 2, Episode 8 Hello, and welcome to the Time Pieces History Podcast. Today, we’re looking at the Farne Islands, just off the coast of Northumberland. As always, shownotes and transcript are on my website, and please leave a comment. The largest of the Farne Islands and one of three which is accessible (there are 28 in total), is Lindisfarne, which is 1.5 miles (2.4 km) north to south and 3 miles (4.8km) east to west. While it has a permanent population of only 160 people, it receives 650,000 visitors every year, many of whom stay in one of its five hotels or rent a holiday cottage. The Anglo-Saxons named the island, which became a religious site when the first monastery was built in 635AD. The two most significant bishops of the monastery are Saint Aidan, who we looked at in episode three of season one, and Saint Cuthbert, who featured in episode four of this season. The monastery at Lindisfarne was the target of the first recorded Viking raid in 793, although the island itself was visited by a group of Norsemen in 787, who killed the reeve sent to escort them to the king. Religious sites were often attacked, and the clergy described the Norsemen as ‘a most vile people’, which was not how they saw themselves. The Norse people considered raiding honourable, where the victor of battle claimed the spoils of war. They were very good at it, because they had superior ships and were committed to the task. -

Habitats Regulation Assessment Welsh National Marine Plan November 2019

Habitats Regulation Assessment Welsh National Marine Plan November 2019 © Crown copyright 2019 WG39253 Digital ISBN 978-1-83933-413-9 Welsh Government Welsh National Marine Plan Habitats Regulations Assessment Habitats Regulations Assessment Wood Environment & Infrastructure Solutions UK Limited – August 2019 2 © Wood Environment & Infrastructure Solutions UK Limited Report for Copyright and non-disclosure notice Welsh Government The contents and layout of this report are subject to copyright Cathays Park owned by Wood (© Wood Environment & Infrastructure Cardiff Solutions UK Limited 2019) save to the extent that copyright CF10 3NQ has been legally assigned by us to another party or is used by Wood under licence. To the extent that we own the copyright in this report, it may not be copied or used without our prior written agreement for any purpose other than the purpose Main contributors indicated in this report. The methodology (if any) contained in Mike Frost this report is provided to you in confidence and must not be disclosed or copied to third parties without the prior written agreement of Wood. Disclosure of that information may constitute an actionable breach of confidence or may Issued by otherwise prejudice our commercial interests. Any third party who obtains access to this report by any means will, in any event, be subject to the Third Party Disclaimer set out below. ................................................................................. Mike Frost Third party disclaimer Any disclosure of this report to a third party is subject to this disclaimer. The report was prepared by Wood at the instruction Approved by of, and for use by, our client named on the front of the report. -

Coastal Landscapes and Early Christianity in Anglo-Saxon Northumbria

Estonian Journal of Archaeology, 2009, 13, 2, 79–95 doi: 10.3176/arch.2009.2.01 David Petts COASTAL LANDSCAPES AND EARLY CHRISTIANITY IN ANGLO-SAXON NORTHUMBRIA This paper explores the ways in which coastal landscapes were used by the early church in Anglo-Saxon Northumbria. The coastal highways were a key element of the socio-political landscape of the Northumbrian kingdom, with many key secular and ecclesiastical power centres being located in proximity to the sea. However, the same maritime landscapes also provided the location of seemingly remote or isolated hermitages. This paper explores this paradox and highlights the manner in which such small ecclesiastical sites were, in fact, closely integrated into a wider landscape of power, through case studies exploring the area around Bamburgh and Holy Island in Northumberland and Dunbar in southern Scotland. David Petts, Lecturer in Archaeology, Durham University, South Road, Durham DH1 3LE, England; [email protected] Introduction The 8th and 9th centuries AD were the Golden Age of Northumbria, the period when the northern Anglo-Saxon kingdom reached its peak in political power, intellectual endeavour and artistic output (Hawkes & Mills 1999; Rollason 2003). The study of this period consistently highlights the importance of a series of key, mainly ecclesiastical, sites: Whitby, Hartlepool, Bamburgh, Lindisfarne and the twin monastery of Monkwearmouth and Jarrow. Even a brief look at a map of early medieval Northumbria will reveal that these sites have coastal or estuarine locations (Fig. 1). The key importance of maritime power and coastal zones in the early medieval period is well established. -

Cardiff Naturalists' Society Newsletter

CARDIFF NATURALISTS’ SOCIETY Founded 1867 NEWSLETTER NO.79 SEPTEMBER 2008 Charity No 1092496 www.cardiffnaturalists.org.uk LIST OF OFFICERS Immediate past President Patricia Wood President Roger Milton Vice President Vacant Secretary Mike Dean 36 Rowan Way Cardiff CF14 0TD 029 20756869 Email [email protected] Treasurer Dr Joan Andrews Rothbury Cottage Mill Road Dinas Powis CF64 4BT Email [email protected] Indoor meetings/Membership Secretary Margaret Leishman 47 Heol Hir Cardiff CF14 5AA 029 20752882 Email [email protected] Field Meetings Secretary Bruce McDonald 5 Walston Close Wenvoe CF5 6AS 02920593394 Email [email protected] Publicity Andy Kendall Shenstone Ty’r Winch Road Old St Mellons Cardiff CF3 5UK Tel 029 20770707 Mob 079 6373 2277 Email [email protected] Edited, published and printed for the Cardiff Naturalists’ Society Brian Bond 22 Douglas Close Llandaff Cardiff CF5 2QT Tel: 029 20560835 Email [email protected] Cover photo Dormouse by Graham Duff at one of our meetings 2 Presidential Ramblings - August 2008 Following my recent return from a few weeks holiday in Hungary, it appears that at long last Summer in the UK has finally arrived. The usual reports of Portuguese man-o-war jellyfish off the South West and Norfolk coasts and the truly delicious taste of freshly picked parasol mushrooms and giant puffballs confirmed that indeed the warmer weather is here. Sadly the recent loss of puffins from the Farne Islands has been noted and the reasons may soon be identified, presumably it is at least in part due to the reduction in food source which has been in steady decline and moving further northwards. -

Lindisfarne Landscapes

Lindisfarne Landscapes The retreat will focus on allowing God to speak to us through the landscape, wildlife and artefacts of the island. There will be guided walks each day, looking at the bird life, geology, flowers, shorelines, beaches, sea and clouds, as well as the well-known attractions such as the castle, priory, village and harbour. We will be using our walks to provide inspiration for artwork for those interested. Pastels and paper, and possibly some textiles, will be provided, but if you prefer to work in a different medium you will need to bring the necessary equipment and materials with you. Experienced artists and complete beginners are both welcome. There will be plenty of guidance available, especially for those with little experience. Anyone not wanting to paint, might want to express their ideas in prose or poetry, or just use the time for rest, birdwatching, reading or visiting the island attractions – you are still welcome! The island has an impressive range of bird-life, especially during the autumn and spring migrations, and wild flowers, which should prove very attractive to those interested in birdwatching or botany. The retreat will be led by Paul Swinhoe and Maureen Simpson. Paul has been visiting the island regularly for over 50 years and hosting retreats there since 2003. He is a bird watcher, artist, member of the Community of Aidan and Hilda and the Secular Order of the Discalced (Teresian) Carmel. Before retirement, he taught Earth Sciences and later Computing, for many years in the further education sector. Maureen is a Methodist Local Preacher, Prayer Guide, Spiritual Director, Group Coordinator for the Community of Aidan and Hilda, retired teacher, trained in Environmental Studies, and artist.