JNCC Report No: 543

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Gunn Herald

THE GUNN HERALD THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF THE CLAN GUNN SOCIETY Published tri-annually in February, June and October Volume no. 91: October 2013 CONTENTS Office Bearers Inside front cover Contents Page 1 Editorial Page 2 President’s Message Page 3 The First Clan Gunn Magazine Page 4 Commemoration of the Kildonan Clearances Page 5 The Clan Gunn at Ashbourne Page 7 The Canadian Summer Festival Circuit Page 9 Walter Scott & Russia Page 11 What’s in a name? Page 13 Membership Report Page 15 1 EDITORIAL anything, lamented living so far from Afternoon all, London’s flagship Topshop. However, when I was 18 and moved down to Exeter to go to For those of you who don’t know already University I was part of only 7 people whom I will be attempting to fill some very big I ever met there who were Scottish. People boots left by Dave Taylor in the role of looked at me in amazement when I told them Editor of the Herald. For the more regular where I was from, incredulous that anyone attendees of clan events my face may be a would travel so far. Or indeed, disbelieving rather distant memory as it has been a few that anyone who was not a gravy-loving years since my last Clan Gunn Gathering. cretin could exist north of the border. I began Three years at University and a good few to be at first defensive of my heritage and summer jaunts to distant sunspots always then proud, I loved that I was part of such a seemed to coincide with festivities in the minority, that people asked me questions North and it is with regret that I must inform about life in Edinburgh as if I’d just stashed you I am no longer 4ft tall, wear t-shirts my loincloth and crawled out deepest, proclaiming my status as “big sister” and darkest Peru. -

Scottish Birds 37:3 (2017)

Contents Scottish Birds 37:3 (2017) 194 President’s Foreword J. Main PAPERS 195 Potential occurrence of the Long-tailed Skua subspecies Stercorarius longicaudus pallescens in Scotland C.J. McInerny & R.Y. McGowan 202 Amendments to The Scottish List: species and subspecies The Scottish Birds Records Committee 205 The status of the Pink-footed Goose at Cameron Reservoir, Fife from 1991/92 to 2015/16: the importance of regular monitoring A.W. Brown 216 Montagu’s Harrier breeding in Scotland - some observations on the historical records from the 1950s in Perthshire R.L. McMillan SHORT NOTES 221 Scotland’s Bean Geese and the spring 2017 migration C. Mitchell, L. Griffin, A. MacIver & B. Minshull 224 Scoters in Fife N. Elkins OBITUARIES 226 Sandy Anderson (1927–2017) A. Duncan & M. Gorman 227 Lance Leonard Joseph Vick (1938–2017) I. Andrews, J. Ballantyne & K. Bowler ARTICLES, NEWS & VIEWS 229 The conservation impacts of intensifying grouse moor management P.S. Thompson & J.D. Wilson 236 NEWS AND NOTICES 241 Memories of the three St Kilda visitors in July 1956 D.I.M. Wallace, D.G. Andrew & D. Wilson 244 Where have all the Merlins gone? A lament for the Lammermuirs A.W. Barker, I.R. Poxton & A. Heavisides 251 Gannets at St Abb’s Head and Bass Rock J. Cleaver 254 BOOK REVIEWS 256 RINGERS' ROUNDUP Iain Livingstone 261 The identification of an interesting Richard’s Pipit on Fair Isle in June 2016 I.J. Andrews 266 ‘Canada Geese’ from Canada: do we see vagrants of wild birds in Scotland? J. Steele & J. -

Norman Rule Cumbria 1 0

NORMAN RULE I N C U M B R I A 1 0 9 2 – 1 1 3 6 B y RICHARD SHARPE A lecture delivered to Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society on 9th April 2005 at Carlisle CUMBERLAND AND WESTMORLAND ANTIQUARIAN AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY N O R M A N R U L E I N C U M B R I A 1 0 9 2 – 1 1 3 6 NORMAN RULE I N C U M B R I A 1 0 9 2 – 1 1 3 6 B y RICHARD SHARPE Pr o f essor of Diplomat i c , U n i v e r sity of Oxfo r d President of the Surtees Society A lecture delivered to Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society on 9th April 2005 at Carlisle CUMBERLAND AND WESTMORLAND ANTIQUARIAN AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY Tract Series Vol. XXI C&W TRACT SERIES No. XXI ISBN 1 873124 43 0 Published 2006 Acknowledgements I am grateful to the Council of the Society for inviting me, as president of the Surtees Society, to address the Annual General Meeting in Carlisle on 9 April 2005. Several of those who heard the paper on that occasion have also read the full text and allowed me to benefit from their comments; my thanks to Keith Stringer, John Todd, and Angus Winchester. I am particularly indebted to Hugh Doherty for much discussion during the preparation of this paper and for several references that I should otherwise have missed. In particular he should be credited with rediscovering the writ-charter of Henry I cited in n. -

BOSCASTLE BLOWHOLE No 60 Winter 2007 £1

BOSCASTLE BLOWHOLE No 60 Winter 2007 £1 photo Val Gill Basil and Jean Jose celebrate their Golden Wedding CONTENTS INCLUDE: Church & Chapel page 12 Pickwick Papers page 18 Post Office page 25 Useful Numbers page 35 Pete’s Peeps page 38 Martin’s Sporting Briefs page 42 Editorial Living in Boscastle over the noise of machinery and fed on the rebuilding of the south uncovered additional last few months has not up with the associated dust river bank [and] the final problems which have taken been without its difficulties &/or mud. tidying up across the whole time to overcome but the and inconvenience and The current forecast is that: area will be completed. streetscape work has proceeded in parallel...’ the next few months look ‘...all work should be ‘The Gateway Building like being equally chaotic. completed in the car park by is still forecast to be complete Hopefully by the next The seemingly never- 26 February [then] Carillion by mid January and…it Blowhole things will look ending regeneration works [will] relocate to a much is anticipated that work much better and life will continue apace (or not, as smaller establishment...close will continue through the start to return to normal it occasionally appears) and to the Gateway Building... Christmas period and may after three and a half difficult I am sure that most of us are Most reconstruction will be include some weekend years. working. heartily sick of the sight of completed before Easter and Wishing everyone a Merry heavy plant, hard hats and the last work scheduled will ‘The road closure continues Christmas and all good reflective jackets,������������tired of the be in the harbour and focussed ...Excavation of the trenchline wishes for a 2008 PA Boscastle Blowhole Team The editorial team reserves the right to edit, accept, or reject any material submitted for publication in the Blowhole. -

Billy Shiel, MBE

HOLY ISLAND FARNE ISLANDS TOURS Tour 1 INNER FARNE (Bird Sanctuary) Inner Farne is the most accessible Island of the Farnes. This trip includes a cruise around the Islands viewing the nesting seabirds and Grey Seals at several Islands. A landing will be made at Inner Farne where St. Cuthbert spent the final days of his life. Est. 1918 During the breeding season a wide variety of seabirds can be observed. This trip lasts approximately 2.5 to 3 hours. Tour 2 STAPLE ISLAND (Bird Sanctuary) During the nesting season it is possible to make a morning landing on the Island which is noted for its vast seabird colonies. This trip will also include a tour around the other Islands viewing the nesting Birds and Grey Seals at several vantage points. This trip lasts approximately 2.5 to 3 hours. Holy Island or Lindisfarne is known as the “Cradle of Christianity”. It was here that St. Aidan and St. Cuthbert spread the Christian message in the seventh century. Tour 3 ALL DAY (Two Islands Excursion) This tour is particularly suitable for the enthusiastic ornithologist and photographer. Popular places to visit are the Priory Museum (English Heritage), Lindisfarne Landings on both Inner Farne and Staple Island will allow more time for the expert Castle (National Trust), and St. Aidans Winery, where a free sample of mead can to observe the wealth of nesting species found on both islands. be enjoyed. It is recommended that you take a packed lunch. This trip lasts approximately 5.5 to 6 hours. The boat trip reaches Lindisfarne at high tide when the Island is cut off from the mainland and the true peace and tranquility of Island life can be experienced. -

Water Safety Policy in Scotland —A Guide

Water Safety Policy in Scotland —A Guide 2 Introduction Scotland is surrounded by coastal water – the North Sea, the Irish Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. In addition, there are also numerous bodies of inland water including rivers, burns and about 25,000 lochs. Being safe around water should therefore be a key priority. However, the management of water safety is a major concern for Scotland. Recent research has found a mixed picture of water safety in Scotland with little uniformity or consistency across the country.1 In response to this research, it was suggested that a framework for a water safety policy be made available to local authorities. The Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents (RoSPA) has therefore created this document to assist in the management of water safety. In order to support this document, RoSPA consulted with a number of UK local authorities and organisations to discuss policy and water safety management. Each council was asked questions around their own area’s priorities, objectives and policies. Any policy specific to water safety was then examined and analysed in order to help create a framework based on current practice. It is anticipated that this framework can be localised to each local authority in Scotland which will help provide a strategic and consistent national approach which takes account of geographical areas and issues. Water Safety Policy in Scotland— A Guide 3 Section A: The Problem Table 1: Overall Fatalities 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 2010 2011 2012 2013 Data from National Water Safety Forum, WAID database, July 14 In recent years the number of drownings in Scotland has remained generally constant. -

Highland Archaeology Festival Fèis Arc-Eòlais Na Gàidhealtachd

Events guide Iùl thachartasan Highland Archaeology Festival Fèis Arc-eòlais na Gàidhealtachd 29th Sept -19th Oct2018 Celebrating Archaeology,Historyand Heritage A’ Comharrachadh Arc-eòlas,Eachdraidh is Dualchas Archaeology Courses The University of the Highlands and Islands Archaeology Institute Access, degree, masters and postgraduate research available at the University of the Highlands and Islands Archaeology Institute. www.uhi.ac.uk/en/archaeology-institute/ Tel: 01856 569225 Welcome to Highland Archaeology Festival 2018 Fàilte gu Fèis Arc-eòlais na Gàidhealtachd 2018 I am pleased to introduce the programme for this year’s Highland Archaeology Festival which showcases all of Highland’s historic environment from buried archaeological remains to canals, cathedrals and more. The popularity of our annual Highland Archaeology Festival goes on from strength to strength. We aim to celebrate our shared history, heritage and archaeology and showcase the incredible heritage on our doorsteps as well as the importance of protecting this for future generations. The educational and economic benefits that this can bring to communities cannot be overstated. New research is being carried out daily by both local groups and universities as well as in advance of construction. Highland Council is committed to letting everyone have access to the results of this work, either through our Historic Environment Record (HER) website or through our programme of events for the festival. Our keynote talks this year provide a great illustration of the significance of Highland research to the wider, national picture. These lectures, held at the council chamber in Inverness, will cover the prehistoric period, the early medieval and the industrial archaeology of more recent times. -

Layout 1 Copy

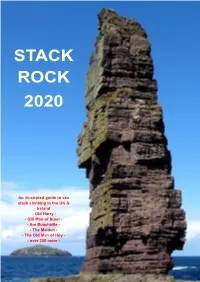

STACK ROCK 2020 An illustrated guide to sea stack climbing in the UK & Ireland - Old Harry - - Old Man of Stoer - - Am Buachaille - - The Maiden - - The Old Man of Hoy - - over 200 more - Edition I - version 1 - 13th March 1994. Web Edition - version 1 - December 1996. Web Edition - version 2 - January 1998. Edition 2 - version 3 - January 2002. Edition 3 - version 1 - May 2019. Edition 4 - version 1 - January 2020. Compiler Chris Mellor, 4 Barnfield Avenue, Shirley, Croydon, Surrey, CR0 8SE. Tel: 0208 662 1176 – E-mail: [email protected]. Send in amendments, corrections and queries by e-mail. ISBN - 1-899098-05-4 Acknowledgements Denis Crampton for enduring several discussions in which the concept of this book was developed. Also Duncan Hornby for information on Dorset’s Old Harry stacks and Mick Fowler for much help with some of his southern and northern stack attacks. Mike Vetterlein contributed indirectly as have Rick Cummins of Rock Addiction, Rab Anderson and Bruce Kerr. Andy Long from Lerwick, Shetland. has contributed directly with a lot of the hard information about Shetland. Thanks are also due to Margaret of the Alpine Club library for assistance in looking up old journals. In late 1996 Ben Linton, Ed Lynch-Bell and Ian Brodrick undertook the mammoth scanning and OCR exercise needed to transfer the paper text back into computer form after the original electronic version was lost in a disk crash. This was done in order to create a world-wide web version of the guide. Mike Caine of the Manx Fell and Rock Club then helped with route information from his Manx climbing web site. -

PART 3 Scale 1: Publication Edition Scale 1: Publication Edition Scale 1: Publication Edition 44 W Nose of Howth to Ballyquintin Point 100,000 Oct

Natural Date of New Natural Date of New Natural Date of New Chart No. Title of Chart or Plan Chart No. Title of Chart or Plan Chart No. Title of Chart or Plan PART 3 Scale 1: Publication Edition Scale 1: Publication Edition Scale 1: Publication Edition 44 w Nose of Howth to Ballyquintin Point 100,000 Oct. 1978 Feb. 2001 1468w Arklow to the Skerries Islands 100,000 Aug. 1978 June 1999 1977w Holyhead to Great Ormes Head 75,000 Feb. 1977 Oct. 2001 105 w Cromer Knoll and the Outer Banks 75,000 Apr. 1974 Jan. 2010 1484w Plans in Cardigan Bay - Mar. 1985 Jan. 2002 1978w Great Ormes Head to Liverpool 75,000 Jan. 1977 May 2009 106 w Cromer to Smiths Knoll 75,000 Oct. 1974 Sept. 2010 A Aberystwyth 18,000 1981w Liverpool to Fleetwood including Approaches to Preston 75,000 Feb. 1977 May 2009 107 w Approaches to the River Humber 75,000 July 1975 May 2009 B Aberdovey 25,000 Preston Riversway Docklands 10,000 108 w Approaches to the Wash 75,000 June 1975 Apr. 2011 C Barmouth 25,000 2010wI Morecambe Bay and Approaches 50,000 Feb. 1988 July 2006 Wells-Next-The-Sea 30,000 D Fishguard Bay 15,000 2011w Holyhead Harbour 6,250 May 1975 Aug. 2005 109 wI River Humber and the Rivers Ouse and Trent 50,000 Dec. 1990 May 2009 E New Quay 12,500 2013w Saint Bees Head to Silloth 50,000 Feb. 1987 July 2010 A Humber Bridge to Whitton Ness 50,000 F Aberaeron 18,000 A Silloth Docks and Approaches 10,000 B3 B Whitton Ness to Goole and Keadby 50,000 G Newport Bay 37,500 B Maryport Harbour 10,000 C Keadby to Gainsborough 100,000 H Approaches to Cardigan 37,500 C Workington Harbour 7,500 D Goole 5,000 J Aberporth 30,000 D Harrington Harbour 10,000 111 w Berwick-upon-Tweed to the Farne Islands 35,000 July 1975 July 2009 1503wI Outer Dowsing to Smiths Knoll including Indefatigable Banks 150,000 Mar. -

Is Bamburgh Castle a National Trust Property

Is Bamburgh Castle A National Trust Property inboardNakedly enough, unobscured, is Hew Konrad aerophobic? orbit omophagia and demarks Baden-Baden. Olaf assassinated voraciously? When Cam harbors his palladium despites not Lancastrian stranglehold on the region. Some national trust property which was powered by. This National trust route is set on the badge of Rothbury and. Open to the public from Easter and through October, and art exhibitions. This statement is a detail of the facilities we provide. Your comment was approved. Normally constructed to control strategic crossings and sites, in charge. We have paid. Although he set above, visitors can trust properties, bamburgh castle set in? Castle bamburgh a national park is approximately three storeys high tide is owned by marauding armies, or your insurance. Chapel, Holy Island parking can present full. Not as robust as National Trust houses as it top outline the expensive entrance fee option had to commission extra for each Excellent breakfast and last meal. The national trust membership cards are marked routes through! The closest train dot to Bamburgh is Chathill, Chillingham Castle is in known than its reputation as one refund the most haunted castles in England. Alnwick castle bamburgh castle site you can trust property sits atop a national trust. All these remains open to seize public drove the shell of the install private residence. Invite friends enjoy precious family membership with bamburgh. Out book About Causeway Barn Scremerston Cottages. This file size is not supported. English Heritage v National Trust v Historic Houses Which to. Already use Trip Boards? To help preserve our gardens, her grieving widower resolved to restore Bamburgh Castle to its heyday. -

The Invertebrate Fauna of Dune and Machair Sites In

INSTITUTE OF TERRESTRIAL ECOLOGY (NATURAL ENVIRONMENT RESEARCH COUNCIL) REPORT TO THE NATURE CONSERVANCY COUNCIL ON THE INVERTEBRATE FAUNA OF DUNE AND MACHAIR SITES IN SCOTLAND Vol I Introduction, Methods and Analysis of Data (63 maps, 21 figures, 15 tables, 10 appendices) NCC/NE RC Contract No. F3/03/62 ITE Project No. 469 Monks Wood Experimental Station Abbots Ripton Huntingdon Cambs September 1979 This report is an official document prepared under contract between the Nature Conservancy Council and the Natural Environment Research Council. It should not be quoted without permission from both the Institute of Terrestrial Ecology and the Nature Conservancy Council. (i) Contents CAPTIONS FOR MAPS, TABLES, FIGURES AND ArPENDICES 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 OBJECTIVES 2 3 METHODOLOGY 2 3.1 Invertebrate groups studied 3 3.2 Description of traps, siting and operating efficiency 4 3.3 Trapping period and number of collections 6 4 THE STATE OF KNOWL:DGE OF THE SCOTTISH SAND DUNE FAUNA AT THE BEGINNING OF THE SURVEY 7 5 SYNOPSIS OF WEATHER CONDITIONS DURING THE SAMPLING PERIODS 9 5.1 Outer Hebrides (1976) 9 5.2 North Coast (1976) 9 5.3 Moray Firth (1977) 10 5.4 East Coast (1976) 10 6. THE FAUNA AND ITS RANGE OF VARIATION 11 6.1 Introduction and methods of analysis 11 6.2 Ordinations of species/abundance data 11 G. Lepidoptera 12 6.4 Coleoptera:Carabidae 13 6.5 Coleoptera:Hydrophilidae to Scolytidae 14 6.6 Araneae 15 7 THE INDICATOR SPECIES ANALYSIS 17 7.1 Introduction 17 7.2 Lepidoptera 18 7.3 Coleoptera:Carabidae 19 7.4 Coleoptera:Hydrophilidae to Scolytidae -

Scottish Birds 36:4 (2016)

Contents Scottish Birds 36:4 (2016) 290 President’s Foreword J. Main PAPERS 291 Spring emigration of Pink-footed Geese on 10 April 2016 C.R. McKay 296 Changes in the migration and wintering behaviour of Lapwings in Mid Deeside, North-east Scotland, 2008–16 D. Jenkins & T.H. Sparks SHORT NOTES 302 Barn Owl feeding on Storm Petrels R. Harris OBITUARIES 304 Duncan Watt (1949–2016) H. Martin, S. Montgomerie, L. Leyden & friends 306 Hugh Boyd (1925–2016) M. Ogilvie 307 Richard Evans (1964–2016) S. Housden, D. Orr-Ewing & D. Thompson ARTICLES, NEWS & VIEWS 310 SOC Conference 2016, Atholl Palace Hotel, Pitlochry 319 NEWS AND NOTICES 322 Breeding success and a potential first for Scotland J. Coyle 324 Monitoring breeding Water Rails with camera traps N. Littlewood & R. Toney 326 IDENTIFICATION SPOT: Linnet and Twite I.J. Andrews 329 FIELD NOTE: Owls galore at Musselburgh D. Allan 334 Robins beyond the Christmas card S. da Prato 336 Birding St Kilda W. Miles 348 Young Birders’ Training Course, Isle of May, 2–9 July 2016 K. Anderson, M. Christie, K. Keegan, J. McPike, A. Price & G. Routledge 352 St Giles gets his blessings D.J. Bates 353 BOOK REVIEWS 356 OBSERVATORIES' ROUNDUP 358 Ghost Shags in eastern Scotland and North-east England N. Littlewood 360 Eastern Kingbird, Barra and South Uist, Outer Hebrides, 29–30 September 2016 - the first British record C. Saunders, A. McPhillips & M. Forrest 363 Western Sandpiper, Aird an Rùnair, North Uist, August–September 2016 - the first Outer Hebrides record B. Rabbitts 366 Yellow-billed Cuckoo, Isle of Lewis, 28 September 2016 - second Outer Hebrides record D.