BBC TV\S Panorama, Conflict Coverage and the Μwestminster

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scotland's 'Forgotten' Contribution to the History of the Prime-Time BBC1 Contemporary Single TV Play Slot Cook, John R

'A view from north of the border': Scotland's 'forgotten' contribution to the history of the prime-time BBC1 contemporary single TV play slot Cook, John R. Published in: Visual Culture in Britain DOI: 10.1080/14714787.2017.1396913 Publication date: 2018 Document Version Author accepted manuscript Link to publication in ResearchOnline Citation for published version (Harvard): Cook, JR 2018, ''A view from north of the border': Scotland's 'forgotten' contribution to the history of the prime- time BBC1 contemporary single TV play slot', Visual Culture in Britain, vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 325-341. https://doi.org/10.1080/14714787.2017.1396913 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please view our takedown policy at https://edshare.gcu.ac.uk/id/eprint/5179 for details of how to contact us. Download date: 26. Sep. 2021 1 Cover page Prof. John R. Cook Professor of Media Department of Social Sciences, Media and Journalism Glasgow Caledonian University 70 Cowcaddens Road Glasgow Scotland, United Kingdom G4 0BA Tel.: (00 44) 141 331 3845 Email: [email protected] Biographical note John R. Cook is Professor of Media at Glasgow Caledonian University, Scotland. He has researched and published extensively in the field of British television drama with specialisms in the works of Dennis Potter, Peter Watkins, British TV science fiction and The Wednesday Play. -

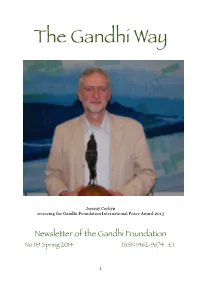

The Gandhi Way

The Gandhi Way Jeremy Corbyn receiving the Gandhi Foundation International Peace Award 2013 Newsletter of the Gandhi Foundation No.119 Spring 2014 ISSN 1462-9674 £1 1 Gandhi Foundation AGM Saturday 24 May 2014 Kingsley Hall, Powis Road, Bromley-By-Bow, London E3 3HJ The AGM will be am and a talk or workshop pm Further details later Gandhi Foundation Summer Gathering 2014 30th anniversary year Gandhian Approaches to Learning and Skills A week of exploring community, nonviolence and creativity through sharing Saturday 26 July - Saturday 2 August The Abbey, Sutton Courtenay, Oxfordshire OX14 4AF The easiest way to apply is by email — please request an application form by emailing [email protected] or from The Organisers Summer Gathering, 2 Vale Court, Weybridge KT13 9NN Tel: 01932 841135 Contents Prospects for Peace Jeremy Corbyn Taxes for Peace Not War – Conscience Youth Faith Groups & Nuclear Disarmament Green Cross Awards, Geneva Diana Schumacher A Gandhi Alphabet (part II) G Paxton & A Copley Book Review: M K Gandhi: Attorney at Law Twisha Chandra Multifaith Celebration 2013 Graham Davey 2 Prospects for Peace 2013 Gandhi Foundation International Peace Award The following are extracts from the acceptance speech by Jeremy Corbyn MP. The full speech is on the GF website. Gandhi saw India as a place where you had to respect all faiths and all religions and then of course he was tragically and cruelly assassinated in 1948. His power and his legacy live on and there are enormous lessons we can all learn from his life. I think, as people go through life now and go on into this century to become more and more challenged by a) the obvious limits of consumerism on the planet, and b) the rush and thirst for war, amongst those that either manufacture arms or those who gain from the manufacture of arms or those who seek to gain from the minerals exploited because of conquests and so on, and there are some very strong lessons to learn from that, but also from the growth of a huge peace movement around the world. -

'Pinkoes Traitors'

‘PINKOES AND TRAITORS’ The BBC and the nation, 1974–1987 JEAN SEATON PROFILE BOOKS First published in Great Britain in !#$% by Pro&le Books Ltd ' Holford Yard Bevin Way London ()$* +,- www.pro lebooks.com Copyright © Jean Seaton !#$% The right of Jean Seaton to be identi&ed as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright Designs and Patents Act $++/. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN +4/ $ /566/ 545 6 eISBN +4/ $ /546% +$6 ' All reasonable e7orts have been made to obtain copyright permissions where required. Any omissions and errors of attribution are unintentional and will, if noti&ed in writing to the publisher, be corrected in future printings. Text design by [email protected] Typeset in Dante by MacGuru Ltd [email protected] Printed and bound in Britain by Clays, Bungay, Su7olk The paper this book is printed on is certi&ed by the © $++6 Forest Stewardship Council A.C. (FSC). It is ancient-forest friendly. The printer holds FSC chain of custody SGS-COC-!#6$ CONTENTS List of illustrations ix Timeline xvi Introduction $ " Mrs Thatcher and the BBC: the Conservative Athene $5 -

198J. M. Thornton Phd.Pdf

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Thornton, Joanna Margaret (2015) Government Media Policy during the Falklands War. Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) thesis, University of Kent. DOI Link to record in KAR https://kar.kent.ac.uk/50411/ Document Version UNSPECIFIED Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html Government Media Policy during the Falklands War A thesis presented by Joanna Margaret Thornton to the School of History, University of Kent In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History University of Kent Canterbury, Kent January 2015 ©Joanna Thornton All rights reserved 2015 Abstract This study addresses Government media policy throughout the Falklands War of 1982. It considers the effectiveness, and charts the development of, Falklands-related public relations’ policy by departments including, but not limited to, the Ministry of Defence (MoD). -

Jihadism in Africa Local Causes, Regional Expansion, International Alliances

SWP Research Paper Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik German Institute for International and Security Affairs Guido Steinberg and Annette Weber (Eds.) Jihadism in Africa Local Causes, Regional Expansion, International Alliances RP 5 June 2015 Berlin All rights reserved. © Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, 2015 SWP Research Papers are peer reviewed by senior researchers and the execu- tive board of the Institute. They express exclusively the personal views of the authors. SWP Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik German Institute for International and Security Affairs Ludwigkirchplatz 34 10719 Berlin Germany Phone +49 30 880 07-0 Fax +49 30 880 07-100 www.swp-berlin.org [email protected] ISSN 1863-1053 Translation by Meredith Dale (Updated English version of SWP-Studie 7/2015) Table of Contents 5 Problems and Recommendations 7 Jihadism in Africa: An Introduction Guido Steinberg and Annette Weber 13 Al-Shabaab: Youth without God Annette Weber 31 Libya: A Jihadist Growth Market Wolfram Lacher 51 Going “Glocal”: Jihadism in Algeria and Tunisia Isabelle Werenfels 69 Spreading Local Roots: AQIM and Its Offshoots in the Sahara Wolfram Lacher and Guido Steinberg 85 Boko Haram: Threat to Nigeria and Its Northern Neighbours Moritz Hütte, Guido Steinberg and Annette Weber 99 Conclusions and Recommendations Guido Steinberg and Annette Weber 103 Appendix 103 Abbreviations 104 The Authors Problems and Recommendations Jihadism in Africa: Local Causes, Regional Expansion, International Alliances The transnational terrorism of the twenty-first century feeds on local and regional conflicts, without which most terrorist groups would never have appeared in the first place. That is the case in Afghanistan and Pakistan, Syria and Iraq, as well as in North and West Africa and the Horn of Africa. -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

Wednesday Volume 494 24 June 2009 No. 98 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Wednesday 24 June 2009 £5·00 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2009 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Parliamentary Click-Use Licence, available online through the Office of Public Sector Information website at www.opsi.gov.uk/click-use/ Enquiries to the Office of Public Sector Information, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 4DU; Tel: 0044 (0) 208876344; e-mail: [email protected] 777 24 JUNE 2009 778 rightly made the case. I hope she will understand when I House of Commons point her to the work of the World Bank and other international financial institutions on infrastructure in Wednesday 24 June 2009 Ukraine and other countries. We will continue to watch the regional economic needs of Ukraine through our involvement with those institutions. The House met at half-past Eleven o’clock Mr. Gary Streeter (South-West Devon) (Con): Given PRAYERS the strategic significance of Ukraine as a political buffer zone between the EU and Russia, does the Minister not think that it was perhaps an error of judgment to close [MR.SPEAKER in the Chair] the DFID programme in Ukraine last year? It would be an utter tragedy if Ukraine’s democracy should fail, so BUSINESS BEFORE QUESTIONS should we not at the very least be running significant capacity-building programmes to support it? SPOLIATION ADVISORY PANEL Resolved, Mr. Thomas: We are running capacity-building programmes on democracy and good governance through That an Humble Address be presented to Her Majesty, That she will be graciously pleased to give directions that there be laid the Foreign and Commonwealth Office. -

The Birth of BBC Radio 4'S Analysis

The Birth of BBC Radio 4’s Analysis Hugh Chignell Hugh Chignell (Ph.D., Bournemouth University, 2005) is a Senior Lecturer in the Bournemouth Media School, Bournemouth University, United Kingdom. His research interests include broadcasting history with special reference to radio and radio archives. He is Chair of the (UK) Southern Broadcasting History Group. BBC Radio 4’s ‘Analysis’ was first broadcast in 1970 and represented a striking departure from the tendency to combine news and comment in radio current affairs. It was created by a small network of broadcasters who believed that current affairs was distinct from radio journalism. The publication of the controversial document ‘Broadcasting in the Seventies’ in 1969 and the outcry which followed it gave this group their opportunity to produce an elite form of radio. INTRODUCTION This article attempts to answer a series of very specific questions. Why was the flag ship BBC radio current affairs program, Analysis created when it was? What specific interpretation of ‘current affairs radio’ did it embody and what made its birth possible? And finally, who created it? Drawing mainly on interview evidence and memoirs of former BBC staff it is possible to answer these questions with some precision and to show the broadcasting context (the BBC in the 1960s) in which the conception of Analysis took place. It is not the intention here to describe the specific nature of the program’s account of current affairs or its decidedly right-leaning politics. This is a case study of how two men, George Fischer and Ian McIntyre, saw their opportunity to buck the populist trend in radio and impose their conservative and Reithian broadcasting values in this elitist experiment in current affairs radio. -

To Download IRAQ, MY COUNTRY Study Guide

KATE RAYNOR STUDYGUIDE ISSUE 36 SCREEN EDUCATION 1 Synopsis Hadi Mahood has been living in Melbourne, Australia, hav- ing fled Iraq in the first Iraq war, a refugee from Samawa in Iraq’s Shiite South. Watching the news broadcasts in Aus- tralia about the war in his country, he has many unanswered questions about the war and decides to return to the city of his birth, filming his journey and the many encounters he has along the way. Flying into Baghdad is currently too dan- gerous, so Hadi lands in Kuwait and then makes a six hour road trip with a truck driver. He is greeted at the Kuwait/Iraq border by his brothers and by corrupt border guards jokingly asking for ‘donations’. e learn a little about Hadi’s guns, guns, guns. Through it all, the background as he travels film is informed by Hadi’s empathy for Waround Samawa. Many years his countrymen and his desperate hope ago, he was an art teacher. (The Ameri- that somehow his homeland can steer cans have bombed the school where its path to some sort of peace and he once worked because Saddam prosperity. Hussein stored weapons there.) He was imprisoned during 1988 for refusing Curriculum Links to attend Saddam Hussein’s student training camps and fight in the Iraq/Iran Iraq, My Country would have relevance War. After his release, he was then to VCE students studying SOSE and forced to join the army for a year. Middle East Politics. Due to scenes of violence, it would not be appropriate From everything we see in Iraq, My for middle or junior secondary stu- Country, this is clearly a place of chaos. -

Terrorist Speech and the Future of Free Expression

TERRORIST SPEECH AND THE FUTURE OF FREE EXPRESSION Laura K. Donohue* Introduction.......................................................................................... 234 I. State as Sovereign in Relation to Terrorist Speech ...................... 239 A. Persuasive Speech ............................................................ 239 1. Sedition and Incitement in the American Context ..... 239 a. Life Before Brandenburg................................. 240 b. Brandenburg and Beyond................................ 248 2. United Kingdom: Offences Against the State and Public Order ....................................................................... 250 a. Treason............................................................. 251 b. Unlawful Assembly ......................................... 254 c. Sedition ............................................................ 262 d. Monuments and Flags...................................... 268 B. Knowledge-Based Speech ................................................ 271 1. Prior Restraint in the American Context .................... 272 a. Invention Secrecy Act...................................... 274 b. Atomic Energy Act .......................................... 279 c. Information Relating to Explosives and Weapons of Mass Destruction............................................ 280 2. Strictures in the United Kingdom............................... 287 a. Informal Restrictions........................................ 287 b. Formal Strictures: The Export Control Act ..... 292 II. State in -

Cteea/S5/20/25/A Culture, Tourism, Europe And

CTEEA/S5/20/25/A CULTURE, TOURISM, EUROPE AND EXTERNAL AFFAIRS COMMITTEE AGENDA 25th Meeting, 2020 (Session 5) Thursday 29 October 2020 The Committee will meet at 9.00 am in a virtual meeting and will be broadcast on www.scottishparliament.tv. 1. Decision on taking business in private: The Committee will decide whether to take item 6 in private. 2. Subordinate legislation: The Committee will take evidence on the Census (Scotland) Amendment Order 2020 [draft] from— Fiona Hyslop, Cabinet Secretary for Economy, Fair Work and Culture, and Jamie MacQueen, Lawyer, Scottish Government; Pete Whitehouse, Director of Statistical Services, National Records of Scotland. 3. Subordinate legislation: Fiona Hyslop (Cabinet Secretary for Economy, Fair Work and Culture) to move— S5M-22767—That the Culture, Tourism, Europe and External Affairs Committee recommends that the Census (Scotland) Amendment Order 2020 [draft] be approved. 4. BBC Annual Report and Accounts: The Committee will take evidence from— Steve Carson, Director, BBC Scotland; Glyn Isherwood, Chief Financial Officer, BBC. 5. Consideration of evidence (in private): The Committee will consider the evidence heard earlier in the meeting. 6. Pre-Budget Scrutiny: The Committee will consider correspondence. CTEEA/S5/20/25/A Stephen Herbert Clerk to the Culture, Tourism, Europe and External Affairs Committee Room T3.40 The Scottish Parliament Edinburgh Tel: 0131 348 5234 Email: [email protected] CTEEA/S5/20/25/A The papers for this meeting are as follows— Agenda item 2 Note by the Clerk CTEEA/S5/20/25/1 Agenda item 4 Note by the Clerk CTEEA/S5/20/25/2 PRIVATE PAPER CTEEA/S5/20/25/3 (P) Agenda item 6 PRIVATE PAPER CTEEA/S5/20/25/4 (P) CTEEA/S5/20/25/1 Culture, Tourism, Europe and External Affairs Committee 25th Meeting, 2020 (Session 5), Thursday 29 October 2020 Subordinate Legislation Note by the Clerk Overview of instrument 1. -

The Parliamentary Bypass Operation

The parliamentary bypass operation by Labour MP Robert Sheldon - reported to This is the story of a scandal. The government has failed to account to Parliament that they wished to 'reaffirm the Parliament for expenditure of half a billion pounds on a secret 'spy' satellite, importance' they attached to the statement 'as a due to be positioned over the Soviet Union. In doing so, it has flagrantly breached means of keeping Parliament reliably informed about the costs and progress of major Defence a solemn promise to inform Parliament, through its public Accounts Committee, projects' . of all major defence expenditure. This was to be the subject of the first At the time the agreement was made in 1982, Sheldon's predecessor as chair of the PAC, Lord programme in a forthcoming BBC2 series Secret Society, written and presented Barnett, wrote that 'full accountability to by New Statesman writer DUN CAN CAMPBELL. Last Thursday, BBC Parliament in future is imperative'. Yet within a year, the government was breaking that agreement director general Alasdair Milne banned the programme. Here, for the first time, by secretly developing Zircon. Campbell is able to tell the story of official deceit. (Additional research by Lord Barnett, ironically, is now the Deputy Chairman of the BBC. The man who made the Jolyon Jenkins and Patrick Forbes) agreement with Barnett was Sir Frank Cooper - then the Ministry of Defence Permanent PROJECT ZIRCON is the secret codename for Permanent Secretaries' Committee on the Secretary, but now a late convert to campaigning Britain's first ever spy satellite. Zircon, originally Intelligence Services (PSIS), and would have then for Freedom of Information and better planned to be launched in 1988, will be a 'signals been passed to the Prime Minister. -

The BBC's Role in the News Media Landscape

The BBC’s Role in the News Media Landscape: The Publishers’ View The BBC Charter Review provides an opportunity for the government to look at the future of the BBC and its evolving role in the wider media landscape. The green paper on Charter Review asks some important questions about the BBC’s scale and scope, funding and governance, and the impact of its ever-growing range of services on commercial media competitors: Does the BBC’s £3.7 billion per year of public funding give it an unfair advantage and distort audience share in a way that undermines commercial business models? Does its huge online presence and extensive free online content damage a wide range of players? Is the BBC able to continue to develop great content to audiences, efficiently and cost effectively while minimising any negative impact on the wider market and maximising any benefits? Is the expansion of the BBC’s services justified in the context of increased choice for audiences? Is the BBC crowding out commercial competition and, if so, is this justified? How should the BBC’s commercial operations, including BBC Worldwide, be reformed? How should the current model of governance and regulation for the BBC be reformed? The News Media Association (NMA), the voice of independent commercial news brands in the UK, believes that the system of BBC governance should place greater obligations on the BBC to work collaboratively – rather than in competition - with the wider news sector. We commissioned Oliver and Ohlbaum Associates (O&O) to examine the changing market for news services and the BBC’s expanding role within that market.