Chapter 5: the United Nations and the Sanctions Against Iraq

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Globalization. Security Crises

“HENRI COANDA” GERMANY “GENERAL M.R. STEFANIK” AIR FORCE ACADEMY ARMED FORCES ACADEMY ROMANIA SLOVAK REPUBLIC INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE of SCIENTIFIC PAPER AFASES 2011 Brasov, 26-28 May 2011 GLOBALIZATION. SECURITY CRISES Iustin ACHIRECESEI, Vasile NODIŞ Introduction further reported that, such a base would not have been conceivable before Poland joined This report examines the implications Nato in 1999. of this strategy in recent years; following the In November of 2007 it was reported emergence of a New Cold War, as well as that, Russia threatened to site short-range analyzing the war in Georgia, the attempts and nuclear missiles in a second location on the methods of regime change in Iran, , the European Union's border yesterday if the expansion of he Afghan-Pakistan war theatre, United States refuses to abandon plans to erect and spread of conflict in Central Africa. These a missile defence shield. A senior Russian processes of a New Cold War and major army general said that Iskander missiles could regional wars and conflicts take the world be deployed in Belarus if US proposals to closer to a New World War. place 10 interceptor missiles and a radar in Peace is only be possible if the tools Poland and the Czech Republic go ahead. and engines of empires are dismantled. Putin also threatened to retrain Russia's nuclear arsenal on targets within Europe. Eastern Europe: Forefront of the New Cold However, Washington claims War that the shield is aimed not at Russia but at In 2002, the Guardian reported that, states such as Iran which it accuses of seeking “The US military build-up in the former to develop nuclear weapons that could one day Soviet republics of central Asia is strike the West. -

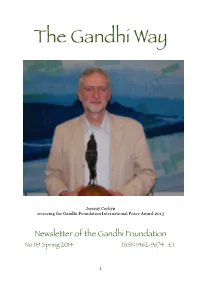

The Gandhi Way

The Gandhi Way Jeremy Corbyn receiving the Gandhi Foundation International Peace Award 2013 Newsletter of the Gandhi Foundation No.119 Spring 2014 ISSN 1462-9674 £1 1 Gandhi Foundation AGM Saturday 24 May 2014 Kingsley Hall, Powis Road, Bromley-By-Bow, London E3 3HJ The AGM will be am and a talk or workshop pm Further details later Gandhi Foundation Summer Gathering 2014 30th anniversary year Gandhian Approaches to Learning and Skills A week of exploring community, nonviolence and creativity through sharing Saturday 26 July - Saturday 2 August The Abbey, Sutton Courtenay, Oxfordshire OX14 4AF The easiest way to apply is by email — please request an application form by emailing [email protected] or from The Organisers Summer Gathering, 2 Vale Court, Weybridge KT13 9NN Tel: 01932 841135 Contents Prospects for Peace Jeremy Corbyn Taxes for Peace Not War – Conscience Youth Faith Groups & Nuclear Disarmament Green Cross Awards, Geneva Diana Schumacher A Gandhi Alphabet (part II) G Paxton & A Copley Book Review: M K Gandhi: Attorney at Law Twisha Chandra Multifaith Celebration 2013 Graham Davey 2 Prospects for Peace 2013 Gandhi Foundation International Peace Award The following are extracts from the acceptance speech by Jeremy Corbyn MP. The full speech is on the GF website. Gandhi saw India as a place where you had to respect all faiths and all religions and then of course he was tragically and cruelly assassinated in 1948. His power and his legacy live on and there are enormous lessons we can all learn from his life. I think, as people go through life now and go on into this century to become more and more challenged by a) the obvious limits of consumerism on the planet, and b) the rush and thirst for war, amongst those that either manufacture arms or those who gain from the manufacture of arms or those who seek to gain from the minerals exploited because of conquests and so on, and there are some very strong lessons to learn from that, but also from the growth of a huge peace movement around the world. -

Iraq: Differing Views in the Domestic Policy Debate

Order Code RL31607 Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Iraq: Differing Views in the Domestic Policy Debate October 16, 2002 name redacted, Meaghan Marshall, name redacted Research Associates Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division name redacted Specialist in National Defense Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Iraq: Differing Views in the Domestic Policy Debate Summary The debate over whether, when, and how to prosecute a major U.S. military intervention in Iraq and depose Saddam Hussein is complex, despite a general consensus in Washington that the world would be much better off if Hussein were not in power. Although most U.S. observers, for a variety of reasons, would prefer some degree of allied or U.N. support for military intervention in Iraq, some observers believe that the United States should act unilaterally even without such multilateral support. Some commentators argue for a stronger, more committed version of the current policy approach toward Iraq and leave war as a decision to reach later, only after exhausting additional means of dealing with Hussein’s regime. A number of key questions are raised in this debate, such as: 1) is war on Iraq linked to the war on terrorism and to the Arab-Israeli dispute; 2) what effect will a war against Iraq have on the war against terrorism; 3) are there unintended consequences of warfare, especially in this region of the world; 4) what is the long- term political and financial commitment likely to accompany regime change and possible democratization in this highly divided, ethnically diverse country; 5) what are the international consequences (e.g., to European allies, Russia, and the world community) of any U.S. -

Verifying European Union Arms Embargoes

Verification Research, Training and Information Centre Verifying European Union arms embargoes Paper submitted to the United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research (UNIDIR) for the European Commission project on ‘European Action on Small Arms, Light Weapons and Explosive Remnants of War’ Disclaimer: The views expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect the views or opinion of the United Nations, UNIDIR, its members or sponsors. 18 April 2005 1 Verifying European Union arms embargoes Introduction 1. Analysis of the current situation 1.1 What is the role of monitoring and verification in making arms embargoes effective? 1.2 EU arms embargoes and UN arms embargoes 1.3 The link between EU arms embargoes and UN arms embargoes 1.4 How EU member states currently implement EU and UN arms embargoes 1.5 Monitoring and enforcing EU and UN embargoes 2. Recommendations 2.1 Drafting EU arms embargoes 2.2 Monitoring and enforcement 2.3 Additional recommendations Annex 1: Table of current EU and UN arms embargoes Introduction1 There are many reasons why sanctions—coercive measures undertaken by a group of nations in an effort to influence another nation into following international law or submitting to a judgment—may be adopted against a state. One of the most common is to improve the human rights situation in the sanctioned state by targeting the perpetrators of human rights abuses, who may be individuals, non-state actors, government elites or the military. They are also used to change the behaviour of a state which is undermining democracy or the rule of law, or which has threatened the security of a particular region. -

BBC TV\S Panorama, Conflict Coverage and the Μwestminster

%%&79¶VPanorama, conflict coverage and WKHµ:HVWPLQVWHU FRQVHQVXV¶ David McQueen This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and due acknowledgement must always be made of the use of any material contained in, or derived from, this thesis. %%&79¶VPanorama, conflict coverage and the µ:HVWPLQVWHUFRQVHQVXV¶ David Adrian McQueen A thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Bournemouth University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2010 µLet nation speak peace unto nation¶ RIILFLDO%%&PRWWRXQWLO) µQuaecunque¶>:KDWVRHYHU@(official BBC motto from 1934) 2 Abstract %%&79¶VPanoramaFRQIOLFWFRYHUDJHDQGWKHµ:HVWPLQVWHUFRQVHQVXV¶ David Adrian McQueen 7KH%%&¶VµIODJVKLS¶FXUUHQWDIIDLUVVHULHVPanorama, occupies a central place in %ULWDLQ¶VWHOHYLVLRQKLVWRU\DQG\HWVXUSULVLQJO\LWLVUHODWLYHO\QHJOHFWHGLQDFDGHPLF studies of the medium. Much that has been written focuses on Panorama¶VFRYHUDJHRI armed conflicts (notably Suez, Northern Ireland and the Falklands) and deals, primarily, with programmes which met with Government disapproval and censure. However, little has been written on Panorama¶VOHVVFRQWURYHUVLDOPRUHURXWLQHZDUUeporting, or on WKHSURJUDPPH¶VPRUHUHFHQWKLVWRU\LWVHYROYLQJMRXUQDOLVWLFSUDFWLFHVDQGSODFHZLWKLQ the current affairs form. This thesis explores these areas and examines the framing of war narratives within Panorama¶VFRYHUDJHRIWKH*XOIFRQIOLFWV of 1991 and 2003. One accusation in studies looking beyond Panorama¶VPRUHFRQWHQWLRXVHSLVRGHVLVWKDW -

Applying Conventional Arms Control in the Context of United Nations Arms Embargoes

Applying conventional arms control in the context of United Nations arms embargoes Acknowledgements Support from UNIDIR core funders provides the foundation for all of the Institute’s activities. This project is supported by the Governments of Germany and Switzerland. This report was made possible through the facilitation and cooperation of former and current members of the Security Council. UNIDIR would like to express its appreciation to the United Nations partners, namely the United Nations Department of Political Affairs, United Nations Mine Action Service and the United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs, which all contributed to this study. Additionally, UNIDIR would like to thank former and current members of the Panel of Experts for their valuable inputs and feedback on this report. This report would not have been possible without the support and close cooperation of all partners mentioned above. Savannah de Tessières drafted this report, with support from Himayu Shiotani, Jonah Leff, Franziska Seethaler and Sebastian Wilkin. Himayu Shiotani edited this report, with support from Sebastian Wilkin and John Borrie. At UNIDIR, Himayu Shiotani managed this project. About UNIDIR The United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research (UNIDIR)—an autonomous institute within the United Nations—conducts research on disarmament and security. UNIDIR is based in Geneva, Switzerland, the centre for bilateral and multilateral disarmament and non-proliferation negotiations, and home of the Conference on Disarmament. The Institute explores current issues pertaining to a variety of existing and future armaments, as well as global diplomacy and local tensions and conflicts. Working with researchers, diplomats, government officials, NGOs and other institutions since 1980, UNIDIR acts as a bridge between the research community and Governments. -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

Wednesday Volume 494 24 June 2009 No. 98 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Wednesday 24 June 2009 £5·00 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2009 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Parliamentary Click-Use Licence, available online through the Office of Public Sector Information website at www.opsi.gov.uk/click-use/ Enquiries to the Office of Public Sector Information, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 4DU; Tel: 0044 (0) 208876344; e-mail: [email protected] 777 24 JUNE 2009 778 rightly made the case. I hope she will understand when I House of Commons point her to the work of the World Bank and other international financial institutions on infrastructure in Wednesday 24 June 2009 Ukraine and other countries. We will continue to watch the regional economic needs of Ukraine through our involvement with those institutions. The House met at half-past Eleven o’clock Mr. Gary Streeter (South-West Devon) (Con): Given PRAYERS the strategic significance of Ukraine as a political buffer zone between the EU and Russia, does the Minister not think that it was perhaps an error of judgment to close [MR.SPEAKER in the Chair] the DFID programme in Ukraine last year? It would be an utter tragedy if Ukraine’s democracy should fail, so BUSINESS BEFORE QUESTIONS should we not at the very least be running significant capacity-building programmes to support it? SPOLIATION ADVISORY PANEL Resolved, Mr. Thomas: We are running capacity-building programmes on democracy and good governance through That an Humble Address be presented to Her Majesty, That she will be graciously pleased to give directions that there be laid the Foreign and Commonwealth Office. -

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning

ISSUE 1 · 2018 TECHNOLOGY TODAY Highlighting Raytheon’s Engineering & Technology Innovations SPOTLIGHT EYE ON TECHNOLOGY SPECIAL INTEREST Artificial Intelligence Mechanical the invention engine Raytheon receives the 10 millionth and Machine Learning Modular Open Systems U.S. Patent in history at raytheon Architectures Discussing industry shifts toward open standards designs A MESSAGE FROM Welcome to the newly formatted Technology Today magazine. MARK E. While the layout has been updated, the content remains focused on critical Raytheon engineering and technology developments. This edition features Raytheon’s advances in Artificial Intelligence RUSSELL and Machine Learning. Commercial applications of AI and ML — including facial recognition technology for mobile phones and social applications, virtual personal assistants, and mapping service applications that predict traffic congestion Technology Today is published by the Office of — are becoming ubiquitous in today’s society. Furthermore, ML design Engineering, Technology and Mission Assurance. tools provide developers the ability to create and test their own ML-based applications without requiring expertise in the underlying complex VICE PRESIDENT mathematics and computer science. Additionally, in its 2018 National Mark E. Russell Defense Strategy, the United States Department of Defense has recognized the importance of AI and ML as an enabler for maintaining CHIEF TECHNOLOGY OFFICER Bill Kiczuk competitive military advantage. MANAGING EDITORS Raytheon understands the importance of these technologies and Tony Pandiscio is applying AI and ML to solutions where they provide benefit to our Tony Curreri customers, such as in areas of predictive equipment maintenance, SENIOR EDITORS language classification of handwriting, and automatic target recognition. Corey Daniels Not only does ML improve Raytheon products, it also can enhance Eve Hofert our business operations and manufacturing efficiencies by identifying DESIGN, PHOTOGRAPHY AND WEB complex patterns in historical data that result in process improvements. -

Sanctions and Human Rights: the Role of Sanctions in International Security, Peace Building and the Protection of Civilian’S Rights and Well-Being

DOCTORAL THESIS SANCTIONS AND HUMAN RIGHTS: THE ROLE OF SANCTIONS IN INTERNATIONAL SECURITY, PEACE BUILDING AND THE PROTECTION OF CIVILIAN’S RIGHTS AND WELL-BEING. CASE STUDIES OF IRAN AND ZIMBABWE. STUDENT: CHIDIEBERE, C. OGBONNA SUPERVISORS: DR. JOSÉ ÁNGEL RUIZ JIMÉNEZ DR. SOFIA HERRERO RICO Castellón, 2016 Dedication To my parents: Nze, George and Lolo, Veronica Ogbonna And to my two brothers: Chukwunyere and Iheanyichukwu And my Love: Chigozie, R. Okeke i Epigraph i will not sit head bent in silence while children are fed sour bread and dull water i will not sit head bent in silence while people rant for the justice of death i will not sit head bent in silence while gossip destroys the souls of human beings i will not sit head bent in silence at any stage of my life and i will depart this world with words spitting from my lips like bullets …too many pass this way heads bent in silence (Alan Corkish, 2003) ii Acknowledgements It has been years of thorough commitment, thorough hard-work and unquantifiable experience. May I use this opportunity to say a big thank you to everybody that contributed in one way or the other to my success, sustenance and improvement over these years of intensive academic pursuit. Of special mention are my parents Nze, George and Lolo, Veronica Ogbonna. Also my appreciation goes to Gabriela Fernández, Barrister Uzoma Ogbonna, Mr. Kelvin Iroegbu, Chinedu Anyanwu, Magnus Umunnakwe and Mr. Lawrence Ubani. More so, it is imperative to acknowledge my past teachers and academic counsellors, who set the stage running through meticulous advice, guidance, inspiration and constructive criticisms. -

Introduction Chapter 1

Notes Introduction 1. Thomas S. Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, 2nd ed. (Chicago: Univer- sity of Chicago Press, 1970). 2. Ralph Pettman, Human Behavior and World Politics: An Introduction to International Relations (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1975); Giandomenico Majone, Evidence, Argument, and Persuasion in the Policy Process (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1989), 275– 76. 3. Bernard Lewis, “The Return of Islam,” Commentary, January 1976; Ofira Seliktar, The Politics of Intelligence and American Wars with Iraq (New York: Palgrave Mac- millan, 2008), 4. 4. Martin Kramer, Ivory Towers on Sand: The Failure of Middle Eastern Studies in Amer- ica (Washington, DC: Washington Institute for Near East Policy, 2000). 5. Bernard Lewis, “The Roots of Muslim Rage,” Atlantic Monthly, September, 1990; Samuel P. Huntington, “The Clash of Civilizations,” Foreign Affairs 72 (1993): 24– 49; Huntington, The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of the World Order (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996). Chapter 1 1. Quoted in Joshua Muravchik, The Uncertain Crusade: Jimmy Carter and the Dilemma of Human Rights (Lanham, MD: Hamilton Press, 1986), 11– 12, 114– 15, 133, 138– 39; Hedley Donovan, Roosevelt to Reagan: A Reporter’s Encounter with Nine Presidents (New York: Harper & Row, 1985), 165. 2. Charles D. Ameringer, U.S. Foreign Intelligence: The Secret Side of American History (Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, 1990), 357; Peter Meyer, James Earl Carter: The Man and the Myth (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1978), 18; Michael A. Turner, “Issues in Evaluating U.S. Intelligence,” International Journal of Intelligence and Counterintelligence 5 (1991): 275– 86. 3. Abram Shulsky, Silent Warfare: Understanding the World’s Intelligence (Washington, DC: Brassey’s [US], 1993), 169; Robert M. -

Montana Model UN High School Conference

Montana Model UN High School Conference Security Council Topic Background Guide Topic 1: The Situation in Iraq1 19 August 2014 According to the UN Charter, the Security Council has primary responsibility for maintaining international peace and security. For decades, the situation in Iraq has presented complex and changing challenges to the Council, ranging from concerns about Iraq’s relations with its neighbors (during the Iran-Iraq war of the 1980s and the 1990 Iraqi invasion of Kuwait); to Iraq’s development of weapons of mass destruction and attacks on Iraqi civilians (during the 1980s and 1990s); the 2003 invasion and occupation of Iraq by the US and UK, which resulted in an Iraqi insurgency and civil war; and the conflict between domestic political opponents, specifically the more recent actions by Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) against the Iraqi government. The situation in Iraq is far from stable. Unresolved ethnic tensions among Iraq’s main ethnic groups — the Shiites, Sunni, and Kurds — could exacerbate the present crisis or lead to further conflicts in the future. Finally, there are concerns about regional stability. The situation within Iraq is also far from resolved from the point of view of Iraqi civilians, who suffered both under the authoritarian government of Saddam Hussein, in the eight years of war that began with the US invasion, and under the attacks by insurgents that followed the US’s withdrawal. Because the US and Iraqi governments refused for many years to release data on civilian casualties, the number of civilian deaths can only be estimated. The most reliable estimates are considered to be those of the Iraq Body Count (IBC), which bases its estimates on media reports. -

The European Union and Burma: the Case For

The European Union and Burma: The Case for Targeted Sanctions Produced by the Burma Campaign UK Tel: 020 7324 4710 March 2004 The report has been endorsed by the following organisations: ♦Actions Birmanie, Belgium ♦Asienhaus, Germany ♦Burma Bureau Germany ♦Burma Campaign UK ♦Burma Centrum Netherlands ♦Committee for the Restoration of Democracy in Burma (Germany) ♦Danish Burma Committee ♦Finnish Burma Committee ♦Infobirmanie, France ♦Norwegian Burma Committee ♦Swedish Burma Committee ♦The International Confederation of Free Trade Unions (endorses the recommendations of this report) Table of Contents Foreword........................................................................................................................................................ 4 Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Recommendations.................................................................................................................................. 6 1. Introduction................................................................................................................................................ 7 2. The Problem ............................................................................................................................................... 7 3. Fuelling the Oppression ........................................................................................................................... 7 4. The Costs...................................................................................................................................................