Building Sustainable Housing on the U.S.-Mexico Border: Insights From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tecate Logistics Press Release

NEWS RELEASE OFFICE OF THE UNITED STATES ATTORNEY SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA San Diego, California United States Attorney Laura E. Duffy For Further Information, Contact: Assistant U. S. Attorney Timothy C. Perry (619) 546-7966 For Immediate Release President of San Diego Customs Brokers Association Pleads Guilty to Overseeing $100 Million Customs Fraud NEWS RELEASE SUMMARY - November 15, 2012 United States Attorney Laura E. Duffy announced that Gerardo Chavez pled guilty today in federal court before United States Magistrate Judge Karen E. Crawford to overseeing a wide-ranging conspiracy to import Chinese and other foreign-manufactured goods into the United States without paying import taxes (also referred to as Customs duties). According to court documents, Chavez=s scheme focused on purchasing large, commercial quantities of foreign-made goods and importing them without paying Customs duties. Wholesalers in the United States would procure commercial shipments of, among other things, Chinese-made apparel and Indian-made cigarettes, and arrange for them to be shipped by ocean container to the Port of Long Beach, California. Before the goods entered the United States, conspirators acting at Chavez=s direction would prepare paperwork and database entries indicating that the goods were not intended to enter the commerce of the United States, but instead would be Atransshipped@ Ain-bond@ to another country, such as Mexico. This in-bond process is a routine feature of international trade. Goods that travel in-bond through the territory of the United States do not formally enter the commerce of the United States, and so are not subject to Customs duties. -

Lessons from San Diego's Border Wall

RESEARCH REPORT (CBP Photo/Mani Albrecht) LESSONS FROM SAN DIEGO'S BORDER WALL The limits to using walls for migration, drug trafficking challenges By Adam Isacson and Maureen Meyer December 2017 " The border doesn’t need a wall. It needs better-equipped ports of entry, investi- gative capacity, technology, and far more ability to deal with humanitarian flows. In its current form, the 2018 Homeland Security Appropriations bill is pursuing a wrong and wasteful approach. The ex- perience of San Diego makes that clear." LESSONS FROM SAN DIEGO'S BORDER WALL December 2017 | 2 SUMMARY The prototypes for President Trump's proposed border wall are currently sitting just outside San Diego, California, an area that serves as a perfect example of how limited walls, fences, and barriers can be when dealing with migration and drug trafficking challenges. As designated by stomsCu and Border Protection, the San Diego sector covers 60 miles of the westernmost U.S.-Mexico border, and 46 of them are already fenced off. Here, fence-building has revealed a new set of border challenges that a wall can’t fix. The San Diego sector shows that: • Fences or walls can reduce migration in urban areas, but make no difference in rural areas. In densely populated border areas, border-crossers can quickly mix in to the population. But nearly all densely populated sections of the U.S.-Mexico border have long since been walled off. In rural areas, where crossers must travel miles of terrain, having to climb a wall first is not much of a deterrent. A wall would be a waste of scarce budget resources. -

Globally Globally Ecosystem

ECONOMIC OPPORTUNITY PROMISE COLLABORATION ECONOMIC OPPORTUNITYINNOVATIONCOMPETITIVENESS EFFICIENCY COLLABORATIONPROMISECREATIVITY EFFICIENCY ECONOMIC COLLABORATION BORDERLESS CREATIVITY OPPORTUNITYPROMISEBORDERLESS PROMISE OPPORTUNITY COMPETITIVENESSCREATIVITY PROMISE BORDERLESS OPPORTUNITY BORDERLESS BORDERLESS COLLABORATION INNOVATION GLOBALLY OPPORTUNITY ENTREPRENEURIAL EFFICIENCY PROMISE PROMISE ECOSYSTEM CONNECTED INNOVATION PROMISECOLLABORATION COLLABORATION COLLABORATION COLLABORATION EFFICIENCY MULTICULTURALCREATIVITY BINATIONALOPPORTUNITY BORDERLESSCREATIVITYPROMISE MULTICULTURALPROMISE EFFICIENCY ECONOMIC ECONOMIC PROMISEOPPORTUNITY ECONOMIC EFFICIENCY CREATIVITY BORDERLESS OPPORTUNITY COLLABORATION OPPORTUNITY COLLABORATION OPPORTUNITY ENTREPRENEURIALOPPORTUNITY PROMISE CREATIVITY PROMISE MULTICULTURAL MULTICULTURAL PROMISE PROMISE BORDERLESS CREATIVITY COLLABORATION OPPORTUNITY PROMISE PROMISE OPPORTUNITYCOMPETITIVENESS BINATIONAL GLOBALLY ENTREPRENEURIALBORDERLESS INNOVATION CONNECTED COMPETITIVENESS EFFICIENCY EFFICIENCY EFFICIENCY CREATIVITY ECONOMIC OPPORTUNITYINNOVATION PROMISE CREATIVITY PROMISE COLLABORATIONPROMISE INNOVATION PROMISE BORDERLESS ECONOMIC COLLABORATION OPPORTUNITYBORDERLESS COMPETITIVENESS COMPETITIVENESSCREATIVITY PROMISE ECOSYSTEM BORDERLESS BORDERLESSGLOBALLY COLLABORATION OPPORTUNITY ENTREPRENEURIAL OPPORTUNITY PROMISE CONNECTED INNOVATION PROMISECOLLABORATION COLLABORATION COLLABORATION COLLABORATION EFFICIENCY MULTICULTURALCREATIVITY BINATIONALOPPORTUNITY BORDERLESS CREATIVITYPROMISE MULTICULTURALPROMISE -

Transboundary Issues and Solutions in the San Diego/Tijuana Border

Blurred Borders: Transboundary Impacts and Solutions in the San Diego-Tijuana Region Table of Contents 1. Executive Summary 4 2 Why Do We Need to Re-think the Border Now? 6 3. Re-Defining the Border 7 4. Trans-Border Residents 9 5. Trans-National Residents 12 6. San Diego-Tijuana’s Comparative Advantages and Challenges 15 7. Identifying San Diego-Tijuana's Shared Regional Assets 18 8. Trans-Boundary Issues •Regional Planning 20 •Education 23 •Health 26 •Human Services 29 •Environment 32 •Arts & Culture 35 8. Building a Common Future: Promoting Binational Civic Participation & Building Social Capital in the San Diego-Tijuana Region 38 9. Taking the First Step: A Collective Binational Call for Civic Action 42 10. San Diego-Tijuana At a Glance 43 11. Definitions 44 12. San Diego-Tijuana Regional Map Inside Back Cover Copyright 2004, International Community Foundation, All rights reserved International Community Foundation 3 Executive Summary Blurred Borders: Transboundary Impacts and Solutions in the San Diego-Tijuana Region Over the years, the border has divided the people of San Diego Blurred Borders highlights the similarities, the inter-connections County and the municipality of Tijuana over a wide range of differ- and the challenges that San Diego and Tijuana share, addressing ences attributed to language, culture, national security, public the wide range of community based issues in what has become the safety and a host of other cross border issues ranging from human largest binational metropolitan area in North America. Of particu- migration to the environment. The ‘us’ versus ‘them’ mentality has lar interest is how the proximity of the border impacts the lives and become more pervasive following the tragedy of September 11, livelihoods of poor and under-served communities in both San 2001 with San Diegans focusing greater attention on terrorism and Diego County and the municipality of Tijuana as well as what can homeland security and the need to re-think immigration policy in be done to address their growing needs. -

Conservación De Vegetación Para Reducir Riesgos Hidrometereológicos En Una Metrópoli Fronteriza

e-ISSN 2395-9134 Estudios Fronterizos, nueva época, 17(34) julio-diciembre de 2016, pp. 47-69 https://doi.org/10.21670/ref.2017.35.a03 Artículos Conservación de vegetación para reducir riesgos hidrometereológicos en una metrópoli fronteriza Vegetation conservation to reduce hidrometeorological risks on a border metropoli Yazmin Ochoa Gonzáleza* (http:// orcid.org/0000-0002-8441-7668) Lina Ojeda-Revaha (http:// orcid.org/0000-0001-6006-8128) a El Colegio de la Frontera Norte, Departamento de Estudios Ambientales y de Medio Ambiente, Tijuana, Baja California, México, correos electrónicos: [email protected], [email protected] Resumen El cambio de uso del suelo afecta la dinámica del paisaje especialmente en las ciudades, lo que incrementa el riesgo ante eventos meteorológicos extre- mos y reduce la capacidad de resiliencia. La Zona Metropolitana de Tijua- na-Tecate-Rosarito, con topografía accidentada, pocas áreas verdes, alta bio- diversidad y endemismos, presenta riesgos de deslaves e inundaciones. Se propone crear infraestructura verde (red de áreas verdes) sobre pendientes pronunciadas, cursos de agua y áreas con biodiversidad especial. Con estas va- Recibido el 8 de julio de 2015. riables e imágenes de satélite se construyeron mapas de usos del suelo y vege- Aceptado el 19 de enero de 2016. tación y escenarios de conservación, se analizó su conectividad y su factibilidad legal. Gran parte de la vegetación con alta conectividad se conserva solo cum- pliendo la legislación de no construir en áreas de riesgo. Al sumar las áreas con *Autor para correspondencia: Yazmin Ochoa González, correo biodiversidad especial, aumenta la superficie a conservar y su conectividad. -

Tecate and Calexico Border Infrastructure Projects Request For

May 14, 2019 RE: Tecate and Calexico Primary Fence Replacement Projects To Whom It May Concern: The U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) is seeking your input concerning the replacement of the legacy primary pedestrian fence with a bollard style wall on the east and west sides of the Tecate and Calexico Ports of Entry in California. The preliminary locations for the replacement and construction of bollard wall are shown in Figures 1 and 2 below. CBP proposes to: (1) remove and replace approximately 15 miles of existing pedestrian fence with a bollard wall along the international border near the communities of Tecate and Calexico, California. The existing fence is outdated and will be replaced with a 30-foot bollard wall. Approximately 4.0 miles of fence will be replaced near Tecate, California (Figure 1) and approximately 11 miles will be replaced near Calexico, California (Figure 2). Figure 1: Map of San Diego Wall Replacement Project, Tecate Port of Entry Page 2 Figure 2: Map of El Centro Wall Replacement Project, Calexico Port of Entry CBP is seeking input on potential project impacts to the environment, culture, and commerce, including potential socioeconomic impacts, and quality of life. CBP will be conducting environmental site surveys and assessments and is also gathering data and input from state and local government agencies, federal agencies, Native American tribes, and the general public that may be affected by or otherwise have an interest in the project. CBP will prepare environmental planning documents to evaluate potential environmental impacts and make those documents available to the public. -

2.1 Description of Border Function

TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 1.1 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................................2 1.2 COMMUNITY AND PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT .........................................................................................................4 1.3 EXISTING CONDITIONS ANALYSIS AND ASSESSMENT ......................................................................................4 1.4 PROGRAMMED IMPROVEMENTS AND FUTURE CONDITIONS .............................................................................5 1.5 ORIGIN AND DESTINATION SURVEY RESULTS ..................................................................................................5 1.6 RECOMMENDED PROJECTS .................................................................................................................................5 1.7 FUNDING STRATEGY AND VISION .....................................................................................................................7 2.0 INTRODUCTION 8 2.1 DESCRIPTION OF BORDER FUNCTION ...............................................................................................................9 2.2 DEMOGRAPHIC DATA ...................................................................................................................................... 12 2.3 CROSSING AND WAIT TIME SUMMARIES ......................................................................................................... 14 2.4 ENVIRONMENTAL, HEALTH, -

4 Tribal Nations of San Diego County This Chapter Presents an Overall Summary of the Tribal Nations of San Diego County and the Water Resources on Their Reservations

4 Tribal Nations of San Diego County This chapter presents an overall summary of the Tribal Nations of San Diego County and the water resources on their reservations. A brief description of each Tribe, along with a summary of available information on each Tribe’s water resources, is provided. The water management issues provided by the Tribe’s representatives at the San Diego IRWM outreach meetings are also presented. 4.1 Reservations San Diego County features the largest number of Tribes and Reservations of any county in the United States. There are 18 federally-recognized Tribal Nation Reservations and 17 Tribal Governments, because the Barona and Viejas Bands share joint-trust and administrative responsibility for the Capitan Grande Reservation. All of the Tribes within the San Diego IRWM Region are also recognized as California Native American Tribes. These Reservation lands, which are governed by Tribal Nations, total approximately 127,000 acres or 198 square miles. The locations of the Tribal Reservations are presented in Figure 4-1 and summarized in Table 4-1. Two additional Tribal Governments do not have federally recognized lands: 1) the San Luis Rey Band of Luiseño Indians (though the Band remains active in the San Diego region) and 2) the Mount Laguna Band of Luiseño Indians. Note that there may appear to be inconsistencies related to population sizes of tribes in Table 4-1. This is because not all Tribes may choose to participate in population surveys, or may identify with multiple heritages. 4.2 Cultural Groups Native Americans within the San Diego IRWM Region generally comprise four distinct cultural groups (Kumeyaay/Diegueno, Luiseño, Cahuilla, and Cupeño), which are from two distinct language families (Uto-Aztecan and Yuman-Cochimi). -

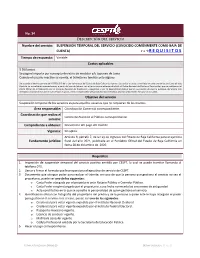

Ir a →R E Q U I S I T

No. 34 Descripción del servicio Nombre del servicio: SUSPENSIÓN TEMPORAL DEL SERVICIO (CONOCIDO COMÚNMENTE COMO BAJA DE CUENTA) Ir a R E Q U I S I T O S Tiempo de respuesta: Variable Costos aplicables $ 500 pesos Se paga el importe por concepto de retiro de medidor y/o taponeo de toma. Cuando el usuario reactive su cuenta, el trámite no tendrá costo alguno. De acuerdo al décimo párrafo del ARTÍCULO 9 de la Ley de Ingresos del Estado de Baja California, vigente: Las tarifas y cuotas contenidas en cada una de las secciones de este Capítulo, se actualizarán mensualmente, a partir del mes de febrero, con el factor que se obtenga de dividir el Índice Nacional de Precios al Consumidor, que se publique en el Diario Oficial de la Federación por el Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, o por la dependencia federal que en sustitución de ésta lo publique, del último mes inmediato anterior al mes por el cual se hace el ajuste, entre el citado índice del penúltimo mes inmediato anterior al del mismo mes que se actualiza. Objetivo del servicio Suspensión temporal de los servicios es para aquellos usuarios que no requieran de los mismos. Área responsable: Coordinación Comercial correspondiente. Coordinación que realiza el Centro de Atención al Público correspondiente. servicio: Comprobante a obtener: Documento del pago del trámite. Vigencia: No aplica. Artículo 9, párrafo 7, de la Ley de Ingresos del Estado de Baja California para el ejercicio Fundamento jurídico: fiscal del año 2021, publicada en el Periódico Oficial del Estado de Baja California en fecha 28 de diciembre de 2020. -

2013 San Diego

BINATIONAL HAZARDOUS MATERIALS PREVENTION AND EMERGENCY RESPONSE PLAN AMONG THE COUNTY OF SAN DIEGO, THE CITY OF SAN DIEGO, CALIFORNIA AND THE CITY OF TIJUANA, BAJA CALIFORNIA January 14, 2013 Binational Hazardous Materials Prevention and Emergency Response Plan Among the County Of San Diego, the City of San Diego, California, and the City of Tijuana, Baja California January 14, 2013 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION PAGE ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 2005-Present ...................................................................................... iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 2003 .................................................................................................... 6 FOREWORD ............................................................................................................................... 10 PARTICIPATING AGENCIES................................................................................................... 17 BACKGROUND ......................................................................................................................... 23 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 23 1.0 TIJUANA/SAN DIEGO BORDER REGION ................................................................. 25 1.1 General Aspects of the Region ........................................................................................ 25 1.1.1 Historical and Cultural Background ................................................................ 25 1.1.2 Geographic Location -

Designing and Establishing Conservation Areas in the Baja California-Southern California Border Region

DRAFT • NOT FOR QUOTATION Designing and Establishing Conservation Areas in the Baja California-Southern California Border Region Michael D. White, Jerre Ann Stallcup, Katherine Comer, Miguel Angel Vargas, Jose Maria Beltran- Abaunza, Fernando Ochoa, and Scott Morrison ABSTRACT The border region of Baja California in Mexico and California in the United States is a biologically diverse and unique landscape that forms a portion of one of the world’s global biodiversity hotspots. While the natural resources of this border region are continuous and interconnected, land conservation practices on either side of the international boundary that bisects this area are quite different. These binational differences place certain natural resources, ecological processes, and wildlife movement patterns at risk of falling through the cracks of conservation efforts implemented in each country. Thus, effective conservation in this region requires binational cooperation with respect to conservation planning and implementation. This paper describes the differences in land conservation patterns and land conservation mechanisms between Baja California and Alta California (Southern California). The Las Californias Binational Conservation Initiative is discussed as a case study for binational cooperation in conservation planning. Diseñando y Estableciendo Áreas de Conservación en la Región Fronteriza Baja California-Sur de California Michael D. White, Jerre Ann Stallcup, Katherine Comer, Miguel Angel Vargas, Jose Maria Beltran- Abaunza, Fernando Ochoa, y Scott Morrison RESUMEN La región fronteriza de Baja California en México y California en los Estados Unidos es un paisaje único y biológicamente diverso que forma una porción de una de las zonas clave (hotspots) de biodiversidad global en el mundo. Mientras que los recursos naturales de esta región fronteriza son continuos e interconectados, las prácticas de conservación del suelo en ambos lados de la frontera internacional que divide en dos esta área son realmente diferentes. -

San Diego & Arizona Eastern (SD&AE) Railway Fact Sheet

April 2013 Metropolitan Transit System San Diego & Arizona Eastern (SD&AE) Railway OWNER San Diego Metropolitan System (MTS) ROUTE DESCRIPTION Four (4) lines totaling 108 miles. Main Line Centre City San Diego south to San Ysidro/International Border at Tijuana. Total length 15.5 miles. This Line extends through Mexico (44.3 miles) and connects up with the Desert Line. The portion through Mexico, originally constructed as part of the Main Line, is now owned by the Mexican national railways, Ferrocarril Sonora Baja California Line. La Mesa Branch Downtown San Diego east to City of El Cajon. Total length: 16.1 miles. Coronado Branch National City south to Imperial Beach. Total length 7.2 miles. Desert Line Extends north and east from International Border (junction called Division) to Plaster City, where it joins the Union Pacific (UP) Line from El Centro. Total length: 69.9 miles. TRANSIT OPERATOR San Diego Trolley, Inc. (SDTI), a wholly subsidiary of MTS on Main Line and on the La Mesa Branch. Frequency Seven (7) days a week; 4:16 a.m. to 2:00 a.m.; 15-minute headways most of the day on Blue and Orange Lines; 7.5 minute peak hour service on Blue Line; 30-minute evenings. Patronage 97,401 average daily riders (FY 12). FREIGHT OPERATOR Private operators, San Diego & Imperial Valley (SD&IV) Railroad on three (3) lines: Main Line, La Mesa Branch, and Coronado Branch, and Pacific Imperial Railroad, Inc (PIR) on the Desert Line. Frequency Provides service as needed and at night when the San Diego Trolley is not in operation.